Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4426

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 1

1Consultant Neonatologist, Neonatal Intensive Care, Pediatric Department, Latifa Women and Children Hospital, Dubai Health Authority, UAE

2Consultant Neonatologist and Head of Pediatric Department, Neonatal Intensive Care, Pediatric Department, Latifa Women and Children Hospital, Dubai Health Authority, UAE

3Specialist Registrar, Neonatal Intensive Care, Pediatric Department, Latifa Women and Children Hospital, Dubai Health Authority, UAE

Correspondence: Khaled El-Atawi, Pediatric Department, Latifa Women and Children Hospital, Dubai, UAE

Received: October 25, 2017 | Published: January 10, 2018

Citation: El-Atawi KM, Elhalik MS, Farid AR (2018) Diffuse Neonatal Hemangiomatosis-A Case Report. J Pediatr Neonatal Care 8(1): 00305. DOI: 10.15406/jpnc.2018.08.00305

Cutaneous Hemangiomas are the most commonly occurring tumors of infancy.1 Hemangiomatosis is defined as multiple hemangiomas, mostly five or more. These small cutaneous hemangiomas appear anytime from birth through the first few months of life.2 Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis (DNH) was first observed by Lister in 1938. These lesions are more frequent in premature children and females (4:1 ratio as compared to males). Lesions begin developing during the first trimester of pregnancy between six to ten weeks after gestation. It commences with the formation of masses of rapidly dividing endothelial cells with or without lumen and a basement membrane that is multi‒laminated. In the involution phase, the lumen dilates and the endothelial cells recede to enable the deposition of fibrous tissue. Completely involuted hemangiomas contain a few capillaries and veins with a flattened endothelium embedded in a stroma of fibrous tissue, collagen, and reticular fibres.3

Recent reports state that many cases reported as DNH in literature are multifocal vascular anomalies such as multifocal lymphangio‒endotheliomatosis (MLT) with thrombocytopenia, which has a significantly higher mortality rate than infantile hemangiomas.4 Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis (DNH) is an extremely rare condition characterized by numerous cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas that emerge during the neonatal period or at birth. Cutaneous lesions often generalized and range from 50 ‒ 500 in number with a size from 0.5 ‒ 1.5 cm in diameter. Visceral lesions are most often found in the liver, CNS, intestine, and lungs. There have been reports of skeletal involvement. Around 60% of infants with DNH die during the first few months of life because of high output cardiac failure, haemorrhage, or cardiac involvement.5 The main cause of the high mortality rate is due to arterio‒venous shunting causing hyperdynamic circulation and high‒output cardiac failure. The high cardiac output leads to congestive heart failure, presenting with poor growth or feeding, tachycardia, tachypnea, cardiac murmur, abdominal distension, or hepatomegaly. Other possible complications include liver failure, consumption coagulopathy, as well as cutaneous, gastrointestinal and cerebral bleeding.1 In most cases, hepatic hemangiomas are asymptomatic and only rarely cause major complications. Despite being histologically benign, this disease is associated with a mortality rate between 50% and 90%.6

We present a case of a new‒born baby with DNH with cutaneous, hepatic and muscular lesions. The male child was delivered by an emergency Lower Segment Caesarean Section (LSCS) at 30‒weeks preterm due to antepartum haemorrhage. At birth, the baby was born limp with severe bradycardia and hypotonia. The baby was intubated and shifted to intensive care for further management. The Apgar score was six and eight, at one and five minutes, respectively.

Preliminary Investigations and Management

Upon general examination, the baby was pink, weighed 1.41 kg, with bruises over the right eyelid, and had stable vital signs. Systemic examination revealed a soft abdomen, with no organomegaly, premature male genitalia with retractile testes and scrotal oedema.

Chest X‒ray revealed signs of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) that was treated with 3 doses of beractant on separate occasions. Continuous ventilatory support was provided for 61 days and the last mode was pressure support ventilation with volume guarantee setting (PSV+VG). At 40 days, the chest X‒ray showed evidence of Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. This was managed with the Dexamethasone:A randomized trial (DART) protocol, wherein dexamethasone was administered for nine days.

At admission, the baby was treated with ampicillin, gentamycin, and piperacillin‒tazobactam regimen for six days, although the blood culture reports were negative. CRP value was 21, and CBC reports were normal. On Day 20, CBC results indicated leucocytosis and absolute neutrophilia. Baby received different courses of antibiotics based on peripheral colonisation with Sphingomonas paucimobilis and Enterobacter cloaceae.

Ultrasonography of the brain at admission was normal. Two weeks later, the baby suffered from severe bradycardia and desaturation that was managed by resuscitating with cardiac massage and administration of two doses of adrenaline intravenously. Spastic hypertonia with hyper‒reflexia of both the upper extremities were noted. On day 20 baby had an attack of tonic colic seizures that was managed with a loading dose of phenobarbitone 20mg/kg. After three weeks, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain examinations and a repeated brain ultrasound were normal. EEG examination revealed significant asymmetry between the two hemispheres with abnormally low amplitude waves and intermittent sharp waves on the left side. The baby was kept on a maintenance dose of phenobarbitone 5mg/kg/day. The baby had a second attack of myoclonic seizures at seven weeks after birth, which was treated with Levetiracetam loading 40 mg/kg followed by maintenance of 20 mg/kg BD. A 2D ECHO test done on day 3, showed moderate to large patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and a small atrial septal defect as a secondary finding.

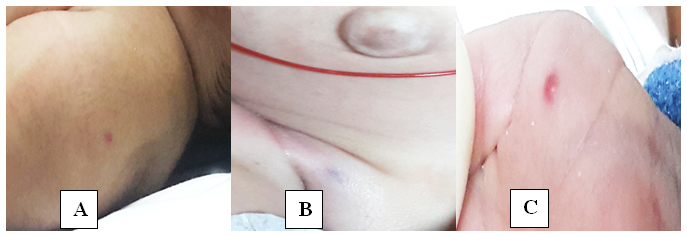

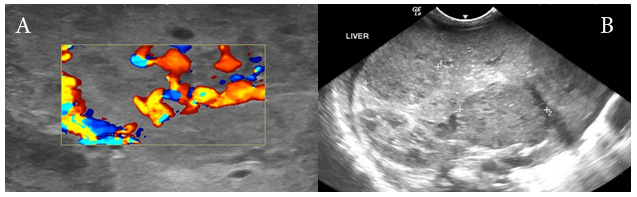

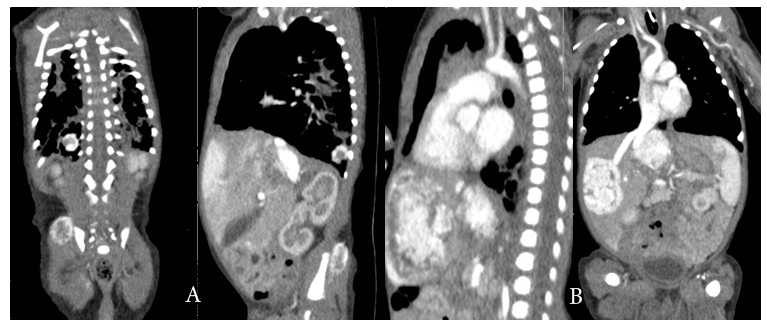

On day 30 of life baby started to show red papular lesions over palm of right hand, left shoulder and pubic region, each sized about two mm (Figure 1 A, B and C) for which the following investigations were done:Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed multiple oval hypo‒echoic lesions of different sizes. The largest lesion measured around 3mm×3mm. Doppler examination showed the presence of feeding blood vessels (Figure 2 A and B). A CT examination of the abdomen with contrast was advised for further evaluation of the liver, to aid a differential diagnosis between hemangiomatosis, metastases, and liver abscesses. This revealed enhanced lesions with multiple foci in both the hepatic lobes with arteriovenous shunting in the form of dilated branches of the hepatic artery and prominently draining hepatic veins. It was reported that the lesions could possibly be hemangio‒endothelioma or infantile angiosarcoma. Additionally, the right basal segment of the lower lobes of the lungs and right gluteus maximus muscle revealed lesions with multiple foci, which was presumed to be a secondary deposit (Figure 3 A and B). The tumour marker AFP (20,777 IU/mL), liver functions were normal apart from mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase (513 IU/mL), and total bilirubin (1.9 g/dL). Repeat test after a week revealed decreasing values. Fundoscopy screen on day 33 of age showed ROP stage 1 bilaterally and a repeat follow up after 2 weeks was normal and was instructed for follow up after 6 months.

Figure 1 Red papular lesions each sized about two mm over left shoulder (A), pubic region (B) and palm of right hand (C).

Figure 2 (A) Longitudinal sonogram of the liver showing multiple hypoechoic areas within the liver parenchyma. (B) Doppler examination of these multiple small hemangiomas demonstrating the AV shunting of blood within the hemangioma.

Figure 3 (A) well‒defined 1.2 x 1 cm sized intensely enhancing lesion in the right lower lobe basal segments and 1.7 cm sized focal enhancing lesion noted in the right gluteal region in the gluteus maximus muscle. (B) Multiple focal variable sized intensely enhancing lesion in both hepatic lobes, the largest lesion in the medial segment of left lobe measures 3.5 x 2.7 cm. The lesion in the right hepatic lobe measures 3.3 x 2.2 cm.

A multidisciplinary team consisting of pediatric surgeon, vascular surgeon, dermatologist, interventional radiologist, and pediatric gastroenterologist diagnosed that the baby was suffering from DNH based on the AFP values, ultrasonography and MRI reports, together with other mentioned investigations. Hence, it was advised to start intravenous prednisolone 5 mg OD (2 ‒ 3 mg/kg/day) and PO propranolol 2.5 mg BD (0.5 ‒ 3 mg/kg/ day). Serial follow‒up ultrasound showed a reduction in the size of the hepatic focal lesions, with a stationary course of the lesion in the caudate lobe. The cardiac conditions remained stable after treatment and the child was shifted to its hometown in the Asian continent. However, unfortunately the baby died of sepsis after two weeks

Diagnosing hemangiomas can pose a challenge, because they can be mistaken for hyper‒vascular malignancies of the liver and can coexist (or occasionally mimic) along with other benign and malignant hepatic lesions, such as focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatic adenoma, hepatic cysts, hemangio‒endothelioma, hepatic angiosarcoma, hepatic metastasis, and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Infantile hemangiomas are a common tumor in infancy. It may occur in 5 ‒ 10% of children below the age of one. Hemangiomas typically regress during childhood. Skin and subcutaneous tissues are affected, and the liver is occasionally affected.7,8

Clinically, hepatic hemangiomas are more common in the right lobe of the liver than in the left lobe. Often, hepatic hemangiomas are small and asymptomatic. Most often they are discovered by chance when scanning or imaging the liver for some other reason.9], in our case also all hemangiomas were discovered by chance as well.

Gnarr et al..10] opined that there might be similar demographics between multifocal lesions and diffuse lesions such as massive replacement of the hepatic parenchyma with various proliferating lesions with hyper‒enhancement on MRI. Cardiac failure, hepatomegaly, respiratory distress, and multi‒organ system failure may be present. Additionally, diffuse lesions may also lead to severe hypothyroidism due to massive overproduction of type III iodothyronine deiodinase and leads to acquired hypothyroidism. Further, radiological imaging can prove extremely helpful to further characterize the lesions.10

Hart.11] reported that although infantile hemangiomas regress spontaneously, they are life threatening when associated with congestive heart failure and/or consumptive coagulopathy. Additionally, he also opined that neonates with solitary hepatic hemangiomas had the best outcome. In a retrospective review, the author observed that 117/194 (60.3%) foetuses and neonates had haemangioma. Of these, just 16 (14%) had abnormal levels of AFP.11 In the present case as well, the haemangioma was accidentally identified and diagnosed, when the child was admitted for medical issues after a premature birth.

Recently, new treatments have tried to diminish the mortality rates of DHN; corticosteroids are considered the first line of treatment, it is well known that corticoids produce vasoconstriction, both arteriolar and capillary, and accelerate the involution of hemangiomas. However, it is well described that steroids inhibit the cyclooxygenase and lipooxygenase pathway, with the subsequent lack of prostaglandins synthesis, mainly PGE2, directly stimulating the production of gastric mucus, causing gastric irritation that can induce gastrointestinal bleeding.12 Léauté‒Labrèze et al..13] used propanolol for shrinking severe hemangiomas of infancy with excellent results. Propranolol is a non‒selective beta‒blocker that induces apoptosis of endothelial cells in the capillaries, lowers intravascular pressure of the lesions, and blocks vascular growth factors, mainly vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor. Other treatment option reported in published literature include subcutaneous interferon alpha 2a or 2b, liver radiation, partial liver resection, hepatic artery embolization, and the use of antiangiogenic agents such as vincristine and cyclophosphamide.1 In our case, steroids and propranolol aided in regressing the size of the haemangioma but unfortunately, the baby died due to sepsis.

None.

None.

©2018 El-Atawi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Down Syndrome Day is observed on 21 March 2026 to raise awareness about Down syndrome and to

promote inclusion, early intervention, and quality healthcare for children with genetic conditions. This day highlights the importance

of pediatric monitoring, developmental support, and continued research to improve health outcomes and overall well-being.

Researchers, pediatricians, and healthcare professionals are invited to submit their original research articles, reviews, and clinical

studies related to Down syndrome, neonatal screening, developmental pediatrics, and child health. Manuscripts submitted on the occasion

of World Down Syndrome Day will be eligible for a special publication discount of 30–40% in the Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatal Care (JPNC).

World Down Syndrome Day is observed on 21 March 2026 to raise awareness about Down syndrome and to

promote inclusion, early intervention, and quality healthcare for children with genetic conditions. This day highlights the importance

of pediatric monitoring, developmental support, and continued research to improve health outcomes and overall well-being.

Researchers, pediatricians, and healthcare professionals are invited to submit their original research articles, reviews, and clinical

studies related to Down syndrome, neonatal screening, developmental pediatrics, and child health. Manuscripts submitted on the occasion

of World Down Syndrome Day will be eligible for a special publication discount of 30–40% in the Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatal Care (JPNC).