Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 3

1Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany

2HPO Research Group & Consulting PartG, Germany

Correspondence: Victoria Berg, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany

Received: October 12, 2017 | Published: October 26, 2017

Citation: Berg V, Heidbrink M (2017) Comparison of the Psychological Capital of Founders and Their Employed Top Management. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 8(3): 00482. DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2017.08.00482

This study examines the difference of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) of founders in comparison to their employed top managers in young companies. We use the PCQ (Psychological Capital Questionnaire) developed and tested by Luthans and colleagues to do so. Results were concluded on the basis of 36 responses from founders from Germany and Chile from 27 different young companies and the same number of answers from their respective employed top managers. A t-test for independent samples shows a significantly higher level in three of the four states of PsyCap among founders: self-efficacy, resilience and optimism. Hope is the only state in which founders don’t exhibit a significantly higher level than their employed top managers. Overall, PsyCap of founders is higher than their employees’. The study is concluded with implications and limitations.

Since March 2015, an international research team of seven academics from Germany, Sweden, France and Chile has been investigating “adolescent” organizations in regard to their corporate culture and leadership, communication, and cooperation practices. The average age of all examined organizations was 5years, with a minimum lifetime of 2years, and a maximum of 7years. One general research interest was to contribute to a better understanding of the typical challenges young organizations face, once they’ve moved past the initial start-up phase successfully. Interesting, but unexpected findings emerged as soon as the first quantitative and qualitative data had been collected and analyzed, which gave reason for the setup of this specific research study. A particularly surprising result was obtained through investigation of to the psychometric of the founders of the young companies:

In comparison to the other employees, the founders seemed more confident, optimistic, assertive and determined.

After our initial research and first insights, we came up against the construct of Psychological Capital, which consists of the four states of self-efficacy, optimism, resilience and hope. The construct was developed by Luthans and colleagues.1,2 Until today, the construct has been tested and applied in many different contexts, for example leadership, performance, job satisfaction and well being.3 Furthermore, the development of PsyCap is well explored.4 Concerning the comparison of PsyCap between different groups of people, only little research has been conducted until today. Some studies compare the levels of PsyCap of Americans and non-Americans or young vs. old people.5 However, surprising to us, there is no study, which examines the direct differences of PsyCap between founders and their direct employed top managers. Having a look at the current situation of entrepreneurial activity, it is exactly this comparison that is interesting: According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, the world’s leading study of entrepreneurship, perceived capability and perceived opportunity to start a business is high. For example, in the United States, 53 % of the population (entrepreneurs excluded) believes they have the knowledge and skills to found a business. Additionally, 51% of the population (entrepreneurs excluded) see good opportunities to start up in the area they live in.6 Seeing these numbers, one could assume a high number of entrepreneurs in the United States. Taking a look at the actual numbers however, reveals that only 6,9% of the population aged 18-64, currently owns and manages an established business. Additionally, the number of nascent entrepreneurs is comparatively low with 13, 8%.6 This phenomenon holds true for many other countries.7 The question arises why so many people obviously see themselves skilled enough and perceive good chances to found their own business, yet in the end only few people actually start up. Disregarding all potential economic reasons, and taking a closer look at the psychometric characteristics of an entrepreneur, a higher level of PsyCap of entrepreneurs could be a reasonable explanation for this phenomenon. Motivated by this question, an obvious gap in the research field of PsyCap in the entrepreneurial context, we turned our thoughts and previous impressions of our research project into action. The result is a study that examines the psychometric differences of PsyCap between founders and their employed top managers: We will begin by explaining the origins and the four states of PsyCap. Afterwards, we will give an overview of the status quo of research concerning all antecedents, moderators and mediators of PsyCap and the impact of the construct on different indicators. Additionally, we will apply the construct of PsyCap on the entrepreneurial context and investigate the status quo in this field. Based on these outcomes, we will formulate five hypotheses and analyze them. The results of the online questionnaire, based on the PCQ (Psychological Capital Questionnaire) by Luthans and colleagues, will be analyzed and discussed. Our study is completed by a conclusion consisting of theoretical and managerial implications, as well as study limitations.

The construct of psychological capital

In the late 1990s a change of focus in psychological research took place. Instead of concentrating on mental illnesses and behavioral dysfunctions of people, researchers turned to the positive psychology of people. Fostered mainly by Martin Seligman at Penn University, a former clinical psychologist and researcher on depression issues, human strength and developable psychological capacities took precedence over negative aspects. A new research field was created: Positive Psychology: based on this, two new approaches arose: Positive Organizational Behavior (POB), developed by Luthans and colleagues since 20028 and Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS), developed by Cameron and colleagues since 2003. Whereas POS sees positive psychology from a macro level, POB investigates on a micro level. Luthans defines POB as “the study and application of positively-oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace’.9 The construct of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) was developed in 2002 and has its roots in exactly this new field. It is therefore based on Positive Psychology and uses the micro level approach, POB.9 PsyCap consists of four states: optimism, hope, resilience and self-efficacy. Each state will be explained in the following.

Optimism:The definition of optimism is based on Seligman’s explanation of theconcept. He defines an optimist as a person, who explains positive events with personal, permanent and pervasive causes. On the contrary, negative events are explained by external, temporary and situation-specific causes.10 Optimism used in the construct of PsyCap considers the positive as well as the negative events and evaluates their causes and consequences. Only in a second step one deliberates if success was due to one’s own input or external influences.1,2 Luthans and colleagues sum this up as realistic and flexible optimism defined as “making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future”.1

Hope:Snyder defines hope as a “positive motivational state that is based on aninteractively derived sense of successful

Two aspects are considered in this definition: willpower and waypower. Willpower describes the ambition to achieve one’s goals in general. Waypower focuses on the specific course of action one has to take to achieve goals and the ability to proactively develop alternative pathways.1,2

Resilience:Resilience derives from clinical and positive psychology. Typically,people with high resilience accept reality as it is, hold strong values and believe that life is meaningful.12 Furthermore, they tend to improvise and take risks, as well as openly face adversities.9 Luthans describes resilience of PsyCap as “the positive psychological capacity to rebound, to “bounce back” from adversity, uncertainty, conflict, failure or even positive change, progress and increased responsibility”.8 Interestingly, people, who failed, bounce back to an even higher level of their personal selves.1

Self-Efficacy:Self-Efficacy or confidence is based on the social cognitive theoryof Bandura.13 Very confident people know about their abilities, trust in them and know when and how to use them. Confidence helps to set challenging goals and tasks and achieve them, as well as to manage and control motivation and the learning process.14 Applied to the working context, Stajkovic and Luthans defined Self-Efficacy as “an individual’s conviction (or confidence) about his or her abilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, and courses of action necessary to successfully execute a specific task within a given context”.15

Overall PsyCap:In many studies, the conceptual independence16 and discriminant validity of PsyCap have been tested.17 Furthermore, Luthans and colleagues found out that the construct of PsyCap as a whole is a better indicator of performance and satisfaction in the workplace than the four factors separated. Therefore, Psychological Capital is considered to be “a higher order core construct”.1

Why is PsyCap so important and relevant? Three reasons constitute its meaning and relevancy. First, PsyCap can be measured. Luthans and his colleagues developed a 24-item, self-rating questionnaire, the PCQ (Psychological Capital Questionnaire), which is psychometrically supported and validated.14‒16 Second, PsyCap is state-like and therefore developable. It is proven that 1-3hour, highly focused micro-interventions already lead to a significant increase of PsyCap.4 Third, a high level of PsyCap has a significant, positive impact on work-related performance and satisfaction.1 Therefore, a potential competitive advantage and a higher job satisfaction can be attained. A detailed description of all antecedents, mediators, moderators and effects of and on PsyCap, which have been detected so far, can be found in the following chapter.

Antecedents of PsyCap

In the following we will provide an overview of the status quo of research on the antecedents of PsyCap, as well as the impacts of PsyCap and its moderators and mediators. Furthermore, insights on the research of PsyCap, tested with Entrepreneurs are given. Seeing PsyCap in its entirety, Luthans and colleagues found out that the construct itself is the result of three different antecedents:

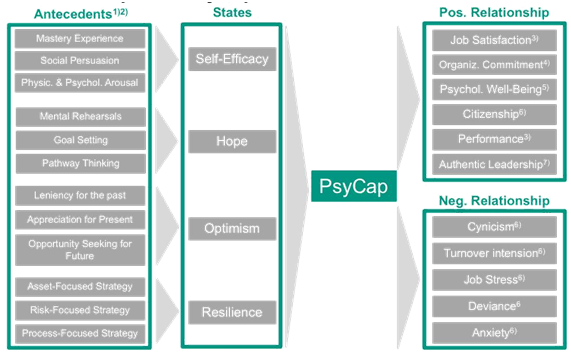

Firstly, the development depends on the “traditional economic capital” like finances and tangible assets: what you have. Secondly, “human capital”, or what you know, is important. Here, experience, education, knowledge and ideas play a major role. Human capital then leads to the third factor, “social capital”, who you know, which is determined by relationships, friends and a network of contacts. These in turn make up “psychological capital”, which characterizes who you are. As already described, PsyCap consist of four states: self-efficacy, hope, optimism and resilience.18 The graphic below gives an overview of all relationships with PsyCap. As pictured, the four states of PsyCap also have their own antecedents. Mainly based on the research of Luthans & Youssef, Luthans, Avolio,1,3,5 the antecedents are described. Self-efficacy depends on the degree of mastery experience. Luthans and Youssef explain that it is important to experience success, reached through achievable, but challenging tasks. In combination with positive feedback and an imagined successful self, social persuasion as well as physical and psychological arousal, self-efficacy grows.18 Hope is determined by three main rules. Firstly, Luthans and Youssef point out that one has to set goals and break down big goals into many small steps. At the same time, it is important to enjoy the way towards achieving the goal and be prepared to re-goal in case of impossible achievements. By mental rehearsal, upcoming goals and alternative pathways can be visualized. The higher these attitudes, the higher hope.1‒18 According to Schneider, three approaches are important for a high state of optimism. One has to accept failures of the past and forgive oneself for it: leniency for the past. Furthermore, one has to be thankful for things one can influence but also for the ones one cannot influence: appreciation for the present. Lastly, one should also see uncertainties of the future as opportunities: opportunity seeking for the future.19 Luthans and Youssef also found out that a good stress management and work-life balance foster realistic and flexible optimism.18 Resilience depends on three different strategies: asset-focused, risk-focused and process-focused strategy. All have the common goal to maximize the probability of a positive outcome.18 Concerning the overall PsyCap, Youssef-Morgan and Luthans found out that a cross-cultural leadership leverages the overall score of the CEO´s of big and small firms.20

Relationships with PsyCap

Taking a look at the right part of Figure 1, one can see the positive and negative impacts of PsyCap. The relationships can be divided into employee attitudes, employee behavior and performance.5 According to Avey and colleagues, the impact of PsyCap on employee attitude and behavior is moderated by the level of positive emotions. This in turn is mediated by the level of mindfulness.21 PsyCap is positively correlated with employee attitudes, such as job satisfaction,1 organizational commitment21 and psychological well being.3 A high level PsyCap is also related to negative attitudes like cynicism, turnover intentions, job stress and anxiety.3 Furthermore, in a Meta analysis, Avey and colleagues found out that beneficial employee behavior, like citizenship, is positively related with PsyCap and adverse behavior, such as deviance, in turn, negatively related with it.5 Many studies prove a high performance goes hand in hand with a high level of PsyCap. Performance was always measured subjectively, by supervisors, and objectively, with KPIs. All methods of performance measurement showed the same results.1‒5 Already in 2004, Luthans & Youssef1 found out that the highest correlation consists between PsyCap and performance.1 These results have not been disproven so far. In general, there is proof that the general level of PsyCap is higher in the United States in comparison to non-U.S. countries and in the service sector in comparison to the manufacturing sector. In contrast, there is no significant difference in the level of PsyCap between students and working adults.5

Figure 1 Antecedents, states and impact of PsyCap.

1)Luthans & Youssef, 2004); 2) Luthans, Youssef & Avolio, 2007); 3)(Luthans et al. 2007); 4)(Avey, Wernsing & Luthans, 2008); 5)Avey et al. 2010); 6)(Avey et al. 2011); 7)(Luthans & Jensen, 2006).

PsyCap in the entrepreneurial context

There is little research on PsyCap in the entrepreneurial context. However, Neil and colleagues found out that the four states hope, optimism, resilience and self-efficacy influence the creation of new venture processes positively.22 Jensen & Luthans4 found a positive relation between PsyCap of entrepreneurs and their perceived authentic leadership.4 Furthermore, Baron and his colleagues found proof that entrepreneurs perceive a lower level of stress than other employees, when having a high level of PsyCap. This negative relationship is stronger for younger entrepreneurs.23 Although there is only little research on PsyCap of entrepreneurs, some studies investigate the different states of PsyCap of entrepreneurs. Already in 1988, Cooper and colleagues found proof for higher levels of optimism in entrepreneurs, who see the future as favorable.24 In a study in the tourist sector, a positive influence of optimism on the success of business was shown. This effect is greater for women than for men.25 Jensen and Luthans found a positive relationship between the level of hope and satisfaction for business owners.16 Additionally, goal setting fosters motivation and performance (Bandura and Locke 2003). Concerning the state resilience, there is proof that resilient people tend to be more effective in a fuzzier world.26 Since entrepreneurs live in a fuzzy world with high risk and unexpected outcomes, this holds true for them. As for optimism, resilience is also a predictor of success for entrepreneurs.25 It has been established that entrepreneurs are high in self-efficacy. For example, Chen, Green and Crick demonstrated that in comparison to management and psychology students, entrepreneurial students have high levels of self efficacy in innovation, risk-taking, marketing, financial control and management.27 In addition, people, who are very confident, are likely to found new companies. Like optimism and resilience, self efficacy is positively related with the success of new ventures.14 In a nutshell, only very little research on PsyCap of entrepreneurs is available today. In particular, no studies have collected analyzed and evaluated evidence of the direct differences between PsyCap of founders and non-founders.

Putting together the insights we gained about “adolescent” organizations from the research project, as well as our research on literature, we suggested the following hypotheses. Having a high level of self-efficacy means being extraordinarily confident and being aware about one’s abilities.15 These characteristics in turn lead to the ability to set challenging goals and at least try to cope with difficult situations. To be able to found one’s own business, one should have exactly these abilities. Not only being confident in founding a business, but also being confident in all its consequences, for example leading a team or presenting one´s ideas. Chen, Greene and Crick already provided proof that entrepreneurs are extraordinarily confident.27 Considering entrepreneurs prior to starting a business, people with high levels of self-efficacy are more likely to found than people with low levels.

Hypothesis 1: Founders have a higher level of self-efficacy than their employed top managers.

Today we live in a V.U.C.A. world, a world that is Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. Especially founders have to face volatile opportunities, take risky decisions with uncertain outcomes, work in complex business surroundings and live with an ambiguous future of their start up. Being very resilient means standing up again after experiencing setbacks and failure, managing conflicts and coping with uncertainty. The decision to found one’s own business brings with it a high level of risk and uncertainties. Until a start up is established, one has to put up with failure, decisions with bad outcomes and unexpected negative occurrences. To sum up, the ability to stand up again must be very high for an entrepreneur. Block & Kremen26 already registered high levels of resilience in entrepreneurs in a fuzzy world.26 Furthermore, being resilient also means to be able to manage new, increased responsibility and progress.8 The bigger a new start up, the more progress is made and responsibility increases. Combining the concept of living in a V.U.C.A. world and the characteristics of a highly resilient person, a logical consequence arises:

Hypothesis 2: Founders have a higher level of resilience than their employed top managers.

Being very optimistic also might help to find one’s path in a V.U.C.A. world. One characteristic of an optimist is to forgive failures of the past. As pointed out above, the probability to make mistakes is very high in an entrepreneurial context. Additionally, optimists tend to see opportunities even in high uncertainties and believe in a positive outcome. On the one hand an entrepreneur has to see opportunities and seize them before others do so. On the other hand, since usually no one has ever done what the entrepreneur is about to do, uncertainty of the opportunity rises. Cooper and colleagues already found proof that entrepreneurs tend to see the future as more favorable than non-entrepreneurs.24 We sum up our considerations to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Founders have a higher level of optimism than their employed top managers.

According to Snyder and colleagues, one has a high level of hope if one sets challenging goals, strives to achieve those, but is also able to re-goal in case of unforeseen occurrences.28 Again taking into account that we are living in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world, clinging to one fixed goal is unlikely to lead to a constructive solution of the task, especially not in a risky surrounding, like an entrepreneurial context. Having a high waypower and the willingness and ability to re-goal or find alternative pathways, if necessary, is essential for an entrepreneur. Having a high level of hope also includes enjoying the way towards achieving one’s goals. Often driven by a personal purpose and an emotional connection to the own, established business, entrepreneurs should tend to enjoy the way to their personal goals more than non business owners. Taking all aspects into account, we come to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Founders have a higher level of hope than their employed top managers.

We hypothesize higher levels of the four states of founders in comparison to their employed top managers. As a logical result, the sum of all states of founders must also be higher than the one of their respective top managers. Furthermore, Luthans and colleagues already found the concept of PsyCap to be a higher order core construct 1. We therefore conducted the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: Founders have a higher level of overall psychological capital (PsyCap) than their employed top managers.

The five hypotheses will be tested in the following and results will be discussed.

In order to empirically test these five hypotheses, we collected psychometric data from at least 26 founders and 26 top managers. With a Power of 0.8, a large effect size and a significance level of 0.05, for a t-test for independent samples, a sample size of at least 26 is required. To control for potential noise, we parallelized the two groups in that way that for each founder in the sample, we took one of the top three employed managers of the same young company into account. We employed the PCQ, the self-rating questionnaire on psychological capital developed by Luthans and colleagues. Since the questionnaire is not publicly available, we requested it from mindgarden.com, a publisher of psychological assessments. For the purpose of doing our research, the publisher provided us with a free version of the questionnaire in English and German, as well as instructions on how to use it and analyze results. According to Luthans, Avolio and Avey, the questionnaire consists of 24 questions, which measure the four states of PsyCap.1 The state optimism is measured by level of agreement to statements similar to “I am optimistic about what will happen to me in the future as it pertains to work”, which have been adapted from Scheier and Carver. The state resilience is requested with prompts like “When I have a setback at work, I have trouble recovering from it, moving on”, adapted from Wagnild & Young.29 In order to measure the state self-efficacy, Luthans and colleagues used a subscale, adapted from Parker SK.30 One exemplary statement is “I feel confident analyzing a long-term problem to find a solution”. To measure the state hope questions adapted from Snyder and colleagues were applied like “There are lots of ways around any problem”.28 The PCQ uses a six-point Likert-type scale in which the respondents had the possibility to choose between 1 = “I strongly disagree” and 6 = “I strongly agree”. We sent participants the link to the online-questionnaire via email. The analysis was done by statistical comparison of mean values of the states and two-sided t-tests for independent samples, in order to examine if there are significantly different characteristics between founders and their members of top management. We used SPSS to do the statistical analysis.31‒33

Results

After contacting over 100 startups in Chile and Germany via email and phone, we could collect 103 answers from founders and their employed top managers in 39 different young businesses. 91 answers were completed. We only considered answers from founders with a complementary answer from the corresponding top manager of the same startup. This led us to a final sample size of 72 participants, collected in 27 young businesses, consisting of 36 founders and 36 top managers. All important characteristics of the sample can be seen in Figure 2. In total, 56 men (35 founders, 21 top managers) and 16 women (1 founder, 15 top managers) participated. On average, the founders were 36years old, the top managers 31. The top managers had on average 7.3years of job experience, whereas the founders have already worked for 12.3years on average. There is also a difference in their academic education. The majority of the top managers have a Bachelor’s degree (12) or a Master’s degree (15). Seven top managers have stopped their academic career after high school (7). In contrast, most of the founders have a Master’s degree (22) and three of them even own a PhD. The results of the two-sided t-test for independent samples can be seen in Figure 3. The mean values of each state and PsyCap of the founders was compared to the mean values of the top management. On average, the founders have a level of self-efficacy of 5.6 (SD=0.40), whereas the top managers have a level of 5.2 (SD=0.62). With p=0.002 (t (70) =3.241), the difference between founders and top managers is very significant. Looking at the level of hope, one can see some differences: the top managers answered on average with 4.87 (SD=0.69), the founders with 5.09 (SD=0.55). Even though there is a slight difference, it is not significant (t (70) =1.507; p=0.136). The mean value of resilience of the founders is 5.07 (SD=0.53), the one of the top managers 4.64 (SD=0.57). Due to p=0.002 (t (70) =3.275), the difference is significant. Also the difference of the mean values of optimism (founder = 4.81, SD=0.69; top manager = 4.35, SD=0.62) are very significant (t (70) =3.059; p=0.003). As a result, the overall average PsyCap is also higher for founders (mean = 5.15, SD=0.43) than for their employed top managers (mean = 4.77, SD=0.50). With p=0.001 (t (70) =3.489), the difference is highly significant. The highest scores were reached in the state self-efficacy with 5.6 by the founders, the lowest in the state optimism by the top managers with 4.35. The biggest difference between mean value of founders and top managers is reached in the state optimism, with a difference of 0.48. In order to make sure the results are not influenced by other variables, we conducted a multiple regression analysis with the depending variable “PsyCap” (Figure 4). The analysis shows that the predictors “highest academic degree”, “gender”, “years of job experience” “position” (founder or employee), “country origin” and “age” explain a significant amount of variance in the level of PsyCap (F (6,65) =2.29, p < 0.05, R2=0.174, R2Adjusted=0.098). However, as expected, the variable “position” (ß= -0.442, t (71) = -3.301, p < 0.05) is the only one with significant impact, while all other variables did not significantly predict the level of PsyCap.

As shown in the previous chapter, except in the state hope, the founders exhibit significantly higher levels of self-efficacy, resilience, optimism and overall PsyCap than their employed top managers. Therefore, we can confirm hypotheses 1; 2; 3 and 5.

Hypothesis 1: Founders have a higher level of self-efficacy than their employed top managers.

Hypothesis 2: Founders have a higher level of resilience than their employed top managers.

Hypothesis 3: Founders have a higher level of optimism than their employed top managers.

Hypothesis 5: Founders have a higher level of overall psychological capital (PsyCap) than their employed top managers.

In turn, hypothesis 4 could not be confirmed. The difference between the average mean of hope of the founders and top managers was insignificant.

Hypothesis 4: Founders have a higher level of hope than their employed top managers.

Even though the overall PsyCap of the founders is significantly higher than the one of their employees, the level of hope of the founders does not significantly differ. We’d like to suggest two possible explanations for this. Firstly, as pointed out above, we live in a V.U.C.A. world. The ability to re-goal and find alternative pathways is essential not only for a founder but for all employees. Setting goals is essential for achieving one’s aims. At the same time, one has to be flexible and be able to adopt the way of how to achieve a goal, due to uncertainty or unexpected incidents. Secondly, especially in a start up, the responsibility of each employee is comparatively high, because of a horizontal hierarchy. Like the founders, the top managers take care of one core business function, for example finance or marketing. As a result, the top managers have to bring the same ability of setting goals, re-goaling and finding alternative pathways. Summing up our results, we can confirm our first impression of a more confident, optimistic and determined founder in comparison to their employees. A higher level of PsyCap can also be one explanation why so many people obviously see themselves skilled enough and perceive good chances to found their own business, yet in the end only few people actually start up.

In our study we examined the parallelized differences of PsyCap between a founder and his/her employed top manager. With the exemption of the state hope, founders scored significantly higher than the top managers in the states resilience, self-efficacy, optimism, as well as in the overall levels of PsyCap. Assuming generality of the results, some interesting implications occur. Since we know founders have a higher level of PsyCap, it is possible to detect potential entrepreneurs by measuring their PsyCap. This can be interesting when it comes to educational, economic and financial support. Students with a high PsyCap and interest in entrepreneurship can be filtered, supported and pushed, for example with a tailored educational program. Combining the results of Luthans and colleagues, who found out that PsyCap can be developed, with our results of higher levels of PsyCap of successful founders, it is worthwhile to focus on the development of PsyCap in students. Especially for the purpose of supporting and pushing new innovations and the founder scene in general, it makes sense to consider the development of PsyCap. While using the results, some limitations have to be considered. Although we used a parallelized sample as a basis to minimize potential noise, the generality of the results has to be considered carefully. With 36 responses of founders and 36 responses of the employed top managers, the sample size is relatively small. Sex of the founder and employee might influence the results since only one female founder and only 15 female employees participated in the study. Firstly, more men than women participated overall in the study and secondly almost all founders were men. This might bias the results. Furthermore, the results cannot be transferred to big companies. Since we only considered young companies, we cannot suggest differences between the top managers of big firms and their employees. The levels of PsyCap among the different levels of management in big companies leave room for further research. Additionally, the results are based on the self-evaluation of the participants. Therefore, one has to be aware of potential noise, due to possible distorted self-perception of the individuals.

We would like to thank the authors of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire, Fred Luthans, Bruce J. Avolio and James B. Avey (2007) for the use of the questionnaire for our research purpose. We would furthermore like to thank mindgarden.com for providing this questionnaire to us.

We hereby declare that no financial resources have been used to conduct the study. No conflict of financial Interest exists. The study has been presented at the 23rd EBES-‐Conference in Madrid. No further publications will arise from this presentation. The study is not under consideration to be published in any other Journals. Therefore, No conflict of interests exists.

None.

©2017 Berg, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.