Journal of

eISSN: 2377-4312

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 4

1Postgraduate in Sciences in Agricultural Production, Universidad Autonoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Mexico

2Postgraduate in Agrarian Sciences, Antonio Narro Agrarian Autonomous University, Mexico

3Instituto Politecnico National, Luego Centro de Biotecnologia Genomica, Laboratorio de Biomedicina Molecular, Mexico

4Department of Parasitology, Universidad Autonoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Mexico

Correspondence: Aldo Ivan Ortega Morales, Universidad Autonoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Deparment of Parasitology, Peripheral and highway to Santa Fe, Torreon, Coahuila, Mexico

Received: April 12, 2018 | Published: July 10, 2018

Citation: Álvarez VHG, Martínez AC, Abdulmakeem AA, et al. Flea (siphonaptera: pulicidae) prevalence and first record of ctenocephalides canis (curtis, 1826) in domestic dogs in north-central Mexico. J Dairy Vet Anim Res. 2018;7(4):146-148. DOI: 10.15406/jdvar.2018.07.00207

The objective of the present study was to report the prevalence of fleas and describe for the first time the presence of Ctenocephalides canis (Curtis) in dogs from Gómez Palacio and Lerdo, Durango, México. A total of 217 dogs were inspected, five of them (2.3%) were parasitized by fleas. The specimens were identified as C. canis and C. felis fleas. The existence of these ectoparasites in domestic dogs is of public and veterinary concern, due to the putative role of this fleas in the transmission of zoonotic pathogens in the study area.

Keywords: fleas, first record, ctenocephalides canis, ctenocephalides felis, domestic dogs, comarca lagunera

The domestic dog is parasitized by arthropods like ticks (Acari: Ixodidae), lice (Insecta: Anoplura), and fleas (Insecta: Siphonaptera). Fleas are wingless, with laterally compresed body, obligate ectoparasites, with a very high specialization to live over its host.1 Commonly, fleas are considered important only as plague of some domestic animals; however, they are important due to its association in the transmission of zoonotic Diseases.2 Around the world 2574 flea species are known, of which in México exist eigth families, and 172 species corresponding to 7% of the total fleas of the world, and the two main families are Ceratophillidae with 74 species and Ctenophthalmidae with 45 species.3 The domestic dog can be parasitized by two main flea species: Ctenocephalides canis (Curtis) and Ctenocephalides felis (Bouché), and the last being considered the most predominant specie worldwide.4 Worlwide, is known that fleas are vectors of pathogenic agents transmitted to humans and animals, some of these microorganisms include Bartonella henselae, Rickettsia felis, R. typhi, and Yersinia pestis;5,6 however, in the last years fleas have been implicated as potential vectors of bacteria belonging to the “Spotted Fever” rickettsia, new genotypes of Bartonella, as well as Coxiella burnetii, Mycoplasma haemominutum, Mycoplasma haemofelis, Anaplasma ovis, A. marginale, A. phagocytophilum, and Ehrlichia canis.7–9

In México, reports exists over the presence of C. canis and C. felis parasitizing domestic dogs in the central and south part of the country;10–12 nevertheless, in the north-central part there are no reports over the presence of these flea species parasitizing domestic dogs. The objective of the present study was to identify the flea species that parasitize domestic dogs of Gomez Palacio and Lerdo, in Durango state, México.

Fleas were collected during june to september 2016 in Gómez Palacio (25°32’ y 25° 54 N, -103°19’ y 103°42 O) and Lerdo (25°10’y 25°47’ N, -103°20’ y -103°49’ O), both cities in Durango state, located at north-central part of México, in an average altitude of 1,150 and 1,140 msnm, respectively. Both cities have a very dry semi-calid climate, with a temperatura ranging from 14-22°C, summer rains (100-400mm), and a scrub and pasture like vegetation (Figure 1).13,14

Each domestic dog in this study was visually inspected, and as described by Rinaldi et al.,15 the sites of predilection by fleas were specially inspected. All specimens were collected manually using entomologic forceps, and deposited in 70% alcohol containing vials, and transferred at the Laboratorio de Biología Molecular, Departamento de Parasitología, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Unidad Laguna. The taxonomic identification of the specimens was realized using stereoscopic microscope (Zeiss Discovery V8), acording to adecuate taxonomic keys.16

A total of 217 female and male domestic dogs of different age and breed were inspected to detect the presence of fleas. Only in five dogs, fleas were observed for a total prevalence of 2.3% (Table 1). For each dog, 30 fleas were collected for a total of 150 specimens, of which, 138 (92%) were consistent with C. felis description, and 12 (8%) with C. canis description. The identification of the specimens was limited only to genera and specie, but not to determine the sex; furthermore, during the study no other flea species were identified.

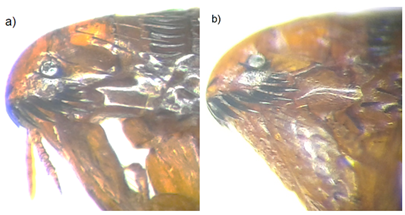

In Figure 2, differences between the two flea species are shown. It could be noted the presence of the pronatal comb (with six spines for both species), as well as the rounded margin in the case of C. canis; however, the head has a mayor longitude and more pronunced angle for C. felis. It is notably to highlight that the two species were found as mixed infestation in the studied dogs; however, C. felis was the most prevalent flea (Table 1), as stated by Beugnet et al.4 In the scientific literature, there are reports over mixed infections by C. canis and C. felis,11,15,17 similar to the observed in our study, were all the positive dogs presented infestation of at least one specimen of both species. It is known that the presence of C. canis as a geographic distibution more restricted, and that the presence of C. felis has increased, even displacing to C. canis, from wich the reasons are not well stablished.11 In the present study, more than 90% of the specimens were C. felis, wich is consistent with the observed in the aforementioned studies.

Our results are in agree with the reported by Beugnet et al.4 who mention that in the domestic dog the most prevalent flea specie around the world is C. felis. In our study, the prevalence observed for C. felis was of 92%, surpassing the 38% reported by Hernández-Valdivia et al.11 in Aguascalientes, México; as well as the 46.4% reported by Orozco-Murillo et al.17 in Valle de Aburrá, Colombia, and the 16.3% reportead by Rinaldi et al.15 in Campania, Italia. The obtained prevalence in this study (2.3%) with respect to C. canis, contrasts with the reported by Nuchjangreed y Somprasong,18 in Pattaya, district of Thailand, where they found this flea specie in a 11.7% of the examined dogs; while Jafari-Sohoorijeh et al.19 in Shiraz, Iran, reported a prevalence of 13.7%, and Cruz-Vázquez et al.10 in Cuernavaca, Morelos a total of 16.8% of C. canis infested dogs on its respective studies. However, Bahrami et al.20 and Jamshidi et al.21 described prevalences as high as 28.8 %, in Islam, and 29.4%, en Tehran, Iran; respectively. While Orozco-Murillo et al.17 in Valle de Aburrá, Colombia, reported a highest prevalence for C. canis (53.6%).

Worldwide, fleas as a special role in the transmission of pathogens; historically, diseases as Plague and Murine Tifus are of the most important in terms of affection of humans. Although the dog is less susceptible to Y. pestis infection, and its role in the dissemination of the disease is not well stablished, epidemiological data supports that some patientes infected with Plague, shared the bed with dogs, suggesting that fleas on these dogs played an important role.22 Furthermore, other pathogens like Bartonella henselae, and some Rickettsia spp, can be transmitted to humans during the exposition to contaminated fleas, that ocasionally feed on humans6. It is important to control this ectoparasites by usig cutaneous or sistemic ectoparasiticides,23 by means of oral administration of natural products24. As well, topical solutions are an excellent option to control fleas, this product could be used to prevent and eradicate infestations.25 Furthermore, other products, can help to prevent reinfestations up to five weeks.26 Even, recent investigations suggests that the utilization of entomophatogenic fungi can be used in order to reduce the employment of chemical products in order to protect animal, human and environmental Health.27

Figure 2 Differences between the two flea species

(a) C. canis. Rounded head on its anterior portion, eyes present. The ctenidia has more than five spines; of which, the spnine I is distinctively short than the spine II.

(b) C. felis. Head more large than wide, eyes present. The ctenidia have six spines. The longitude of the first two spines is aproximately similar.

Locality |

Sample |

Sex |

Specimen |

|

Gómez Palacio |

|

|

C. canis |

C. felis |

1 |

Male |

1 |

29 |

|

2 |

Female |

5 |

25 |

|

3 |

Female |

2 |

28 |

|

Lerdo |

||||

4 |

Female |

2 |

28 |

|

5 |

Female |

2 |

28 |

|

Total |

|

|

12 |

138 |

Table 1 Site, characteristics of the sampled animals and specimen collected in the study

The presence of C. felis and C. canis in domestic dogs should be considered by public health and veterinary autorities, due to the zoonotic risk that could play the pathogens present on these fleas. Further research is needed to determine the role of these ectoparasites in the dissemination of diseases in the study area.

Authors acknowledge to the Mexican Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) for the economic support.

Author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Álvarez, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.