Journal of

eISSN: 2378-3184

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 3

1 Fundación Tortugas del Mar, Colombia

2Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network WIDECAST, Colombia

Correspondence: Karla G Barrientos-Muñoz, Fundación, Tortugas del Mar, Envigado, Antioquia, Colombia

Received: June 16, 2020 | Published: June 30, 2020

Citation: Ramirez-Gallego C, Barrientos-Muñoz KG. Illegal hawksbill trafficking: five years of records of the handicrafts and meat trades of the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. J Aquac Mar Biol . 2020;9(3):101-105. DOI: 10.15406/jamb.2020.09.00284

The hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, is one of four sea turtle species that nest in the Colombian Caribbean. This species has suffered prolonged anthropogenic pressure, primarily in the forms of tortoiseshell trade and consumption of their eggs and meat. We investigated the occurrence of hawksbill products for sale in Cartagena de Indias (Cartagena), Colombia. We found that the sale of hawksbill turtle items was carried out by street vendors only on the streets of the San Diego and La Matuna neighborhoods of the old walled city section. We estimated that 1,800–2,800 items per year were offered for sale during the five years of this study. The majority of items were articles of jewellery (96.2%). The prices of items varied greatly depending on the size, design, quality, season, and the origin of tourists. Two restaurants in the Getsemaní neighborhood were found offering sea turtle meat on their menu. Based on our results, we recommend a heightened awareness campaign aimed at informing tourists of the protected status of hawksbsill, including restrictions on internationally transporting hawksbill products. We also recommend that capacity building is needed for police and environmental authorities, so protective regulations can be enforced for the benefit of the conservation of hawksbills at local and regional levels along the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

Keywords: Eretmochelys imbricata, critically endangered, tortoiseshell trade, CITES, Caribbean, Cartagena de Indias

IUCN, the international union for conservation of nature; CITES, the convention on international trade of endangered species

Sea turtles in Colombia have suffered prolonged anthropogenic pressure, which has contributed to the decline of all five species that use Colombian waters as foraging grounds and beaches as nesting grounds.1 The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) has a circumglobal distribution in tropical and, to a lesser extent, subtropical waters of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans,2 and is one of the four sea turtle species that nest on the Colombian Caribbean coast.1

Historically the hawksbill has been harvested for its eggs and meat. Additionally, the beautiful coloration of hawksbill carapacial shell, which consists of a random mottling of translucent amber with darker tints of deep reddish brown, and its ability to take a high polish, has resulted in hawksbill “tortoiseshell” being long been prized by humans.3 During the 20th Century, millions of hawksbills were harvested, mainly for tortoiseshell markets of Europe, the USA, and Asia, where the shell was used to create hair combs, eyeglass frames, rings, bracelets, spoons, bowls, and other trinkets.4,5

The over-exploitation of eggs, meat, and shell of hawksbill turtles has been recognized as a key threat to their conservation and has greatly contributed to the species being listed as Critically Endangered in The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List.2 Hawksbills and all other sea turtle species are listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES), prohibiting international trade on this species and their products.6

Colombia has extensive national legislation and has signed several international treaties and agreements for protecting sea turtles. At the national level, the hawksbill turtle is listed as Critically Endangered by the Red Book of Reptiles of Colombia1 and in 1977 was the first species of sea turtle to be designated as off limits to hunting in the country, is also included in the Programa Nacional para la Conservación de las Tortugas Marinas y Continentales de Colombia (the National Program for the Conservation of Sea Turtles and Continental Colombia),7 and the Plan Nacional de las Especies Migratorias (the National Plan of Migratory Species).8 However, despite these legal protective measures, there are few sufficient implementation strategies in place to protect hawksbills. Indeed, hawksbill handicrafts are still sold throughout the country without any regulation or enforcement of law.1

The city of Cartagena de Indias, located on the northwest Caribbean coast of Colombia, is the second most popular tourist destination in the country. As of the early 2000s, hawksbill products in Cartagena were commonly observed being sold in markets that catered to both domestic and foreign tourists.9–11 But, at the end of the 2000s, the market situation was unknown. An update on the status of this illegal trade would provide important information for the conservation of this species in the Colombian Caribbean. Our objective was to locate and describe the current level of trade of hawksbill products such as handicrafts and meat in Cartagena de Indias, the central point for international tourism in the area.

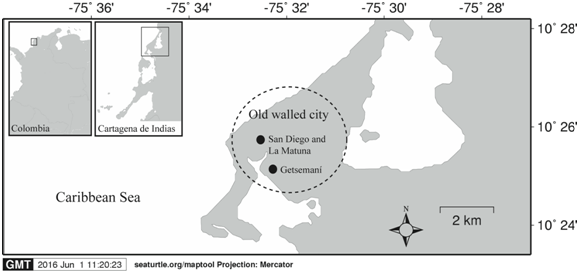

Twice a year from 2008 to 2012, we visited Cartagena de Indias (10º20’N 73º33’ W), specifically to the old walled city which is comprised of three neighborhoods: San Diego, La Matuna, and Getsemaní (Figure 1). Each year, we spent one week during the low tourist season and one week during the high tourist season, identifying and quantifying points of sale of hawksbill handicrafts and sea turtle meat, and numbers and type of hawksbill articles offered in two different types of points of sale: 1. offered by street artisans and vendors; 2. In commercial (souvenir) shops. In addition, we conducted unstructured conversations when possible at the points of sale to ascertain the price, and origin of the crafts and meat. Also, we asked the sellers about the prohibition of the sale of hawksbill crafts and who the main buyers were.

Figure 1 Location of the old walled city of Cartagena de Indias, Caribbean, Colombia, where hawksbill crafts and sea turtle meat are openly sold. The neighborhoods of San Diego and La Matuna are located in the northern part of the old walled city, and Getsemaní in is the southern part.

Notes were taken immediately after surveying each point of sale and supported by photographs and short videos whenever possible. Photographs helped considerably in determining counts of items, especially when many of small items were offered for sale by a single vendor (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Hawksbill turtle items trade in old walled city of Cartagena, Colombia. (A) Jewelry and miscellaneous items sold in street stalls on streets of San Diego and La Matuna neighborhoods in old walled city. (B) Rings and pendants are the two most common items available. (C) Large cooking ladles were uncommon. (D) A Policeman conversing quietly with a hawksbill crafts vendor (the faces are intentionally blurred). In figure 2A and 2D, some coconut shell crafts can be observed.

We estimated the total number of products offered for sale per year by type by averaging the number of products observed at each point of sale where we had good video and photographic coverage, and then multiplying this amount by the number of street artisans and vendors, and souvenir shops that sold these products. Most vendors stocked roughly the same product types, but each vendor sold different amounts of the products. We made adjustments for those street artisans or vendors (N=5) that did not fit within the normal average range.

We present data by year and type of articles being sold, to allow for standardized comparison of our results to other sea turtle trafficking reports, and also future surveys in Cartagena. The retail prices used were the asking prices of the vendors. The exchange rate used in this study is $1942 COL=1 USD (January 2012). The current exchange rate is $3565COL=1USD (June 2020).

During the 2008–2012 surveys, the trade in sea turtle products comprised only one species, the hawksbill turtle. We found that the trade of hawksbill turtle items was carried out only in the streets of San Diego and La Matuna neighborhoods in the old walled city section of Cartagena, and only by street artisans and vendors (Figure 1 & Figure 2A). Conversely, the hawksbill items for sale in any of the 32 souvenirs shops visited annually were never observed in this survey. Store owners know that it is illegal to sell hawksbill products.

During our multiyear survey, we found that 20–37% of the 60 to 65 street vendors and artisans we visited annually offered hawksbill products for sale (Table 1). In 2008, 21 street vendors of hawksbill items were seen at the old walled city of Cartagena, which dropped to 15 in 2009 and 13 street vendors in 2010. Levels rose to 24 vendors selling hawksbill products in 2011 and 2012 (Table 1). All street vendors and artisans surveyed were aware that it was illegal to sell sea turtle products. However, they displayed their ID card permits from City Hall of Cartagena (Alcaldía Mayor de Cartagena de Indias), which supports their activity as artisans-vendors, which apparently includes the sale of hawksbill crafts, in the historical center of the city.

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Street vendors surveyed |

60 |

60 |

65 |

65 |

65 |

|

Street vendors selling hawksbill products |

15 |

21 |

13 |

24 |

24 |

|

Percentage of street vendors selling hawksbill products |

25 |

35 |

20 |

37 |

37 |

|

Estimated range of hawksbill turtle items for sale |

1800 - 2200 |

2100 - 2500 |

2000 - 2200 |

2400 - 2800 |

2200 - 2600 |

|

Restaurants surveyed |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

|

Restaurants selling marine turtle meat |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Table 1 Number and percentage of street vendors surveyed that sold hawksbill turtle items and restaurants that offers marine turtle meat in the old walled city of Cartagena, Colombia, during 2008–2012

The artisans-vendors with ID card permits who sold hawksbill products concentrated in ten main points (Figure 2A), all of which were close to prestigious hotels, restaurants, and shops that are associated with higher income tourists.

The two most common hawksbill craft buyers identified by hawksbill artisans and vendors were US and French, followed by Spanish and Colombian (mainly from the interior of the country). Italians, and nationals from several Latin American countries were also mentioned as hawksbill craft buyers. The purchase and exporting of hawksbill turtle crafts by those international tourists violates not only national laws of Colombia, but also international laws such as CITES, which prohibits the unauthorized transfer of sea turtle products among nations, and national laws of the countries to which they return.

Of the 12 local, traditional food and seafood restaurants surveyed in the old walled city, two were found offering sea turtle meat in their menu (Table 1), such as turtle stew (USD 12), turtle mince (USD 6) or chopped socky (USD 14). Both restaurants were located in the same neighborhood of the old walled city, Getsemaní, where we observed no hawksbill turtle crafts for sale. We were unable to identify which species of sea turtle the meat came from.

An estimated total of 1,800–2,800 hawksbill turtle items per year were observed for sale by vendors during this study (Table 1). Our estimated average of sales per year is 2,593 hawksbill turtle items, comprising 14 different products (Table 2) (Figure 2). All of these were counted separately (except for pendants and earrings which were counted as pairs). The majority were jewelry articles (96.2%), especially rings (32.8%) and pendants (23.1%) (Figure 2B). Meanwhile necklaces (0.6%) and miscellaneous items including cooking ladles (1.2%) (Figure 2C) and butter knifes (0.3%) were uncommon products and offered only by two vendors. Stuffed hawksbill turtles were not seen in the streets for sale. Prices of these items ranged from USD 3 for a ring (Figure 2B) and USD 10 for a teaspoon to USD 40 for a large and elaborate necklace (Table 2), which was one of the most expensive hawksbill items seen during these surveys.

|

Item |

Quantity* |

Price range (USD) |

Price mean (USD) |

Total Value (USD) |

|

Jewellery |

|

|

|

|

|

Rings |

850 |

2.5 – 5 |

3 |

2550 |

|

Pendants (per pair) |

600 |

8 – 12 |

10 |

6000 |

|

Earrings (per pair) |

200 |

5 – 8 |

7.5 |

1500 |

|

Chainbracelets |

200 |

5 – 8 |

6 |

1200 |

|

Bracelets |

350 |

5 - 12.5 |

10 |

3500 |

|

Bangles |

185 |

12.5 – 16 |

15 |

2775 |

|

Hairbands |

45 |

8 – 12 |

10 |

450 |

|

Hairbrooches |

30 |

10 - 12.5 |

12.5 |

375 |

|

Haircombs |

20 |

12 – 15 |

12 |

240 |

|

Necklaces (chain) |

15 |

40 – 50 |

40 |

600 |

|

Miscellaneous |

|

|

|

|

|

Cookingladles |

30 |

25 – 30 |

30 |

900 |

|

Tea spoons |

50 |

10 – 12 |

10 |

500 |

|

Butter knifes |

8 |

12 – 15 |

12.5 |

100 |

|

Large Buckets |

10 |

25 – 40 |

30 |

300 |

|

Total |

2593 |

2.5 – 50 |

– |

20990 |

Table 2 Summary of hawksbill items observed for sale in old walled city of Cartagena, Colombia during 2008-2012

*Quantity is an estimated average of hawksbill items for sale per year by handicrafts type

The price of hawksbill items varied greatly and depended on the size and design (Table 2), the season (low or high tourist season) and the origin of tourists. We observed a 33–60% increase in the prices of the same type of hawksbill items in high tourist season. All street vendors and artisans said they offered their hawksbill items at a higher price to foreign tourists. They claimed that when buyers were not Spanish speakers, the vendors could sell their products at prices two or three times higher, compared to Spanish-speaking tourists. During the five years of surveys, we noted that four artisans sold a large variety of hawksbill items, with each vendor remaining in the same location on the street year after year. Prices of items were similar among all the street vendors surveyed.

Based on conversations with artisans and street vendors, the shells and crafts came from mainly from the Alta Guajira (Guajira Peninsula) in northern Colombia, and to a lesser extent from Corales del Rosario and San Bernardo National Park, 45km southwest of Cartagena Bay.

The police or other law enforcement agents did not challenge the vendors on the legality of selling hawksbill products in this survey. Rather, police officers usually chat with hawksbill artisans and crafts vendors(Figure 2D).

The sale of hawksbill products to tourists in Cartagena has been documented by others.9,10 We found that 20-37% of all observed vendors offered products made from hawksbill shell during 2008-2012, Reuter and Allan (2006) during their survey. This suggests that the sale of hawksbill products has remained fairly steady in Colombia, despite national and international laws prohibiting this. Colombia is signatory to CITES by National Law 17 of 1981. However, there are no official statistics available on the hawksbill sea turtle trade in Colombia, despite the requirement that a report should be submitted annually by CITES Member States in fulfillment of their obligations under Article VIII of CITES. The lack of information makes it difficult to fully assess the threat that trade in hawksbill products poses to the species in the region. There are also several national laws that prohibit the harvest and sale of hawksbill products in Colombia. However, authorities in Cartagena seemed to be unaware of the illegal activity, given that the town hall issued permits for the sale of hawksbill items, and policemen were never observed to challenge vendors on the legality of offering hawksbill products for sale.

Interestingly, none of the commercial shops visited offered hawksbill products. However, Reuter and Allan9 reported that stores in other tourist towns, such as Santa Marta, did offer hawksbill products for sale, in addition to street vendors. It could be that store owners in Cartagena understood that it is illegal to sell hawksbill products, due to several years ago raise awareness campaigns and confiscation actions were carry-out by DepartamentoAdministrativo del Medio Ambiente y de los Recursos Naturales de Cartagena (Administrative Department of Environment and Natural Resources of Cartagena, DAMARENA)12 But unfortunately, these actions were not continuous throughout time – as evidenced in our multiyear census –. Standardized surveys in other tourist towns in Colombia would help to better characterize the differences in outlets for hawksbill products, which in turn could be useful in developing effective mitigation strategies.When asked, the vendors in Cartagena said that the sources for the hawksbill shells and products were coastal regions that are also important areas for foraging and development of juvenile hawksbills and also nesting areas for adult hawksbills.1,11

We suggest that an effort be undertaken to investigate harvest activities of hawksbills in these areas, as well as craftworks that use hawksbill shell. If these activities could be controlled at the source, it would possibly reduce the ability of vendors to sell hawksbill products to tourists illegally in Cartagena and other tourism centers. Indeed, the variation in number of vendors selling hawksbill products across years may reflect changes in availability in product from the coastal sources.

Sea turtle meat was offered in only two observed restaurants, both in the Getsemaní neighborhood, which is less frequented by tourists, thus we suspect it is mostly locals consuming sea turtle meat in these restaurants. It is possible that the number of restaurants selling turtle meat could be higher, but it is not offered openly on the menu. Further investigation of sea turtle meat consumption in Colombia is warranted.

In our study, we observed only four artisans who sold exclusively hawksbill turtle crafts; the majority of artisans and vendors selling hawksbill items also offered a wide variety of crafts with similar appearance to hawksbill items but made of coconut shell (see cooking ladles made in coconut shell in Figure 2A). In Colombia, there is the Artesanías de Colombia (Handicrafts of Colombia), a mixed government and private enterprise project that promotes the development of all economic, social, educational and cultural activities necessary for the progress of the artisans of the country, including crafts made for tourists. This project should support the cultural development of artisans who currently make hawksbill crafts, to facilitate the switch to the manufacture of crafts from other raw material, such as coconut shell, and should contribute in promotion them so that they can sell at a better price.

Our results show the strong uneducated tourism pressure on the hawksbill turtle, while reflecting the lack of knowledge and regulation by government authorities to curb the trade of hawksbill products, increasing the risk of extinction of the depleted populations of the species at local and regional level. Overall, the government of Colombia should allocate sufficient resources for monitoring tortoiseshell harvest and trade and assist with capacity building in local and regional environmental authorities with collaborative structures to further the implementation and enforcement of wildlife trade regulations and its own national laws. In an integrated approach, the government of Colombia also should give support to the artisans that currently sell hawksbill crafts, such that they can transition to working with and/or selling legal products.

We also recommend the establishment of a wide environmental education campaign, where tourists and the general public in Colombia are informed regarding the conservation status of hawksbills and other sea turtles, including the regulations on turtle trade, using clear statements such as: “Do not buy turtle souvenirs or meat. Avoid penalties and jail." It is also important that political leaders at local, regional and the national level enforce currently wildlife legislation that is in place to protect hawksbills. If tourists and locals are disinclined to purchase hawksbill products, this would ultimately reduce the capture of hawksbills and contribute to their conservation at the local and regional level on the Caribbean Coast of Colombia.

We thank the vendors and artisans we interviewed for their collaboration with relevant information. Special thanks to members of the Ramirez Gallego family, who were crucial to the data collection, logistic, lodging and meals during the surveys. The authors acknowledge the use of the Maptool program for analysis and graphics in this paper. Maptool is a product of SEATURTLE.ORG. (Information is available at www.seaturtle.org).13 Our thanks to M. Godfrey, B. Nahill and M. Ferguson for suggestions and helpful comments to improve the manuscript. The authors thank the Fundación Tortugas del Mar, which supported with funds to make this publication.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The authors declare that this type of studies in Colombia to date does not require permits.

None.

©2020 Ramirez-Gallego, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.