Journal of

eISSN: 2378-3184

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 1

1Department of Marine Science and Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Wealth, Oman

2Fisheries Research Center Salalah, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Wealth, Oman

Correspondence: Al-Marzouqi A, Department of Marine Science and Fisheries, MSFC, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Wealth, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman

Received: September 13, 2015 | Published: October 30, 2015

Citation: Al-Marzouqi A, Chesalin M, Al-Shajibi S, Al-Hadabi A, Al-Senaidi R (2015) Changes in the Scalloped Spiny Lobster, Panulirus Homarus Biological Structure after a Shift of the Fishing Season. J Aquac Mar Biol 3(1): 00056. DOI: 10.15406/jamb.2015.03.00056

During 2010, the spiny lobster (Panulirus homarus) fishing season of Oman along the Arabian Sea coast was shifted from 15 October-15 December (2003-2008) to March-April (2010-2014) by the decision of the Ministry of Fisheries. The current status of the spiny lobster stock in the main fishing regions (Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah) was examined based on monthly samples and surveys during the fishing season carried out from 2012 to 2014. An analysis of biological indicators such as size structure, number of undersized individuals captured, size at first maturity, sex composition shows that due to the new fishing season, the state of the lobster stock is improving. However, landings are still relatively low, therefore additional enforcement is needed to control the fishery out of the permitted season.

Keywords: Lobster, Panulirus homarus, Fishery, Size-sex structure, Maturity, Breeding, Growth, Mortality, Yield-per-recruit, Oman, Dhofar, Al-Sharqiyah, Al-Wusta

CL, Carapace Length; SLCA, Shepherd’s Length Composition Analysis; Y/R, Yield-Per Recruit; TB/R, Total Biomass-Per-Recruit; SSB/R, Stock Bbiomass-Per Recruit; CPUE, Catch Per Boat Per Day; Linf , Asymptotic Length

The principal lobster fished in the Sultanate of Oman is the scalloped spiny lobster Panulirus homarus, subspecies P. homarus megasculpta. In Oman, the scalloped spiny lobster is distributed in shallow waters along the Arabian Sea coast from the border with Yemen to Ras-al-Hadd and around Masirah Island.1 Since the late 1980s, the substantial increase in fishing effort has led to drastically reduced catches causing concern on the sustainability of the fishery. The prime reasons attributed for lobster population decline include overfishing, fishing out of a season and improper fishing practices.2-6 Since 1992, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries introduced several measures restricting the lobster fishery to traditional fishers allowing traps, reducing the fishing season from six to two months and prohibited landing of egg-bearing females and lobsters less than 80 mm carapace length. Besides, the Ministry also initiated a monitoring program and research projects (2002-2005 and 2005-2008) to study the basic characteristics of the lobster population and stock assessment along the Oman coast. The results of these works were published by Al-Marzouqi et al.5,7-9 During 2012-2014, the Ministry conducted a new project to collect socio-economic information and to update biological and technical aspects that would assist the authority to develop appropriate strategies to regulate the lobster fishery in the Sultanate of Oman. The results of biological studies presented in this paper are intended to assess consequences of current fishing regulations and to ensure the future sustainable use of the lobster resource.

A sampling program of P. homarus was conducted in three regions (Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah) (Figure 1) from November 2012 to May 2014. Each month, 80 lobsters were collected from four landing sites (Dhalkut and Mirbat in Dhofar, Duqm in Al-Wusta and Ashkharah in Al-Sharqiyah) from fishers, who had received special permission from the Ministry to catch lobsters by traps out of the fishing season. Besides, the measurements of the lobsters were taken during field surveys for three fishing seasons (March-April 2012, 2013 and 2014) in different landing sites of Dhofar by teams of Fisheries Research Center Salalah and in Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah by data collectors of Marine Science and Fisheries Centre. Overall 19 landing sites of Oman were covered by the study, including nine sites in Dhofar (Dhalkut, Salalah, Mirbat, Sadah, Fuoshi, Hadbin, Hasik, Shuwaymiyah, Sharbithat), seven sites in Al-Wusta (Sawqrah, Lakbi, Haitam, Ras Madrakah, Duqm, Mahut, Masirah) and three sites in Al-Sharqiyah (Ashkharah, Asilah, Ruwais) (Figure 1). In Dhalkut and Sadah of Dhofar region, fishers were interviewed to ascertain the depth at which fishing took place, number of nets and the weight of lobsters caught per fishing trip. Information from traders on the number of boats participated in the lobster fishery and the actual landings weighed by traders during a day were also registered during the survey.

Sampled lobsters were measured for carapace length (CL), mid-dorsally from the anterior margin between frontal spines to the posterior carapace edge using vernier calipers to the nearest 0.01 mm and weighed using electronic balance. Sex, stage of female maturity and the presence of external eggs were determined visually. A total of 9454, 4757 and 1845 lobsters were measured in Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah during the study, respectively. Length-weight relationships were calculated for males, females and both sexes combined using a least squares fit and differences between the slopes of the regressions were compared using t-Test test.10 The sex ratio (male: female) was calculated for different years and regions. The percentage occurrence of egg-bearing females and females after releasing eggs was studied to define the breeding season. The cumulated percentages of egg-bearing females in size classes were used to calculate length at first maturity with the logistic formula. Non-linear least squares fitting with Microsoft Excel Solver were used to obtain the best fit.

Non-seasonal Shepherd’s Length Composition Analysis (SLCA) for both sexes combined based the calculation of growth parameters on monthly length-frequency distribution data collected from three main studied regions (Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah) throughout 2013 using the LFDA module of FMSP (Fish Stock Assessment Software).11 The length-frequency distributions were converted to age distributions by age slice method in LFDA software. The coefficient of total mortality (Z) was computed by linearized length-converted catch curves using YIELD software.12 The instantaneous rate of natural mortality (M) was estimated by the empirical method of Pauly at mean annual water temperature of 26 °C. The fishing mortality coefficient (F) was calculated as F=Z–M. The exploitation rate (E) was calculated from the ratio F/Z.13 The estimates were done separately for males and females, for different regions and years. However, these data were combined, because any management regulations are planned for the whole spiny lobster stock in Omani waters. The key parameters were used in yield per recruit analyses with the YIELD program.

The yield-per recruit (Y/R), total biomass-per-recruit (TB/R) and spawning stock biomass-per recruit (SSB/R) were calculated for fishing mortality (F) ranging from 0 to 4. The Beverton and Holt model was selected to describe the stock-recruitment relationship. Reference points for yield per recruit and equilibrium reference points (FMSY, F0.1, target total biomass and target spawning biomass) were estimated separately for studied regions at corresponding parameters of VBGF, L-W relationship, natural mortality, length at first maturity and capture, Beverton-Holt stock-recruitment relationship and the spawning season year-round. The estimations were conducted for the current 2-month fishing season (March–April) and separately for the 7-month fishing season (October–April), assuming illegal fishery out of the season.

Lobster fishery, catch weights and fishing efforts

The lobster is a target of an artisanal fishery by traditional fishers, who catch the animals using bottom set gillnets, traps, spears or just by hands from small motorized fiberglass boats of 6-7 m in length and powered by 40-60 hp outboard engines. The maximum number of boats operating in the lobster fisheries during 2011‒2013 was 628, including 381 in Dhofar, 199 in Al-Wusta and 48 in Al-Sharqiyah. Crew usually comprises of 2–3 persons per boat (mean 2.3). Fishers typically use 3 to 10–12 gillnets (mean 4 nets), but sometimes 20–30 pieces. Each net is about 175 m long, 2–4 m depth and the mesh size varied from 50 mm to 60 mm. The fishing is undertaken in depths between 3 and 20 m. Fishers usually go by boats to remove nets in the early morning (6-7 am), relocate new nets and return to the harbor at noon (10–12 h). A fished area situates closer to the harbor at the opening of the season, then gradually moving away and deeper, but usually not more than 20 km. Fishers also use special plastic lobster traps (cages, pots), (approximately 10-20 traps per boat) in rocky and dense seaweed areas or in a case of strong currents. Traders collect harvested lobsters into freezer trucks and then the lobsters were sorted and packaged at coastal processing factories before supplying to local restaurants or exported to the United Arab Emirates and European countries.

According to the fisheries statistics averaging for 2004–2013, regional exploitation of lobsters accounts for 53% in Dhofar, 34% in Al-Wusta and 13% in Al-Sharqiyah. Historical data show that reported annual landings of P. homarus reached 2,122 tonnes in 1986 and the mean value was approximately 1,500 tonnes between 1985 and 199214 (Figure 2). At this time, the lobster fishery is not regulated and the fishing season lasted approximately six months (October–March), which led to a drastic reduction in stock and catches that decreased more than five times in the mid-1990s. Since 1993, the Ministry introduced 2-month fishing season (December–January) and catches relatively stabilized on the level approximately 434 tonnes during next ten years. Then, following requests of fishers, the Ministry decided to switch the fishing season to 15 October to 15 December since 2003. However, this led to a further decline of catches to only about 158 tonnes in 2008. Based on scientific studies, which showed maximum number of berried females during autumn months (October–November)7,8 the Ministry closed lobster fishing in 2009 and shifted the season to March 1 – April 30 since 2010. It has had some positive results, because catch increased to 407 tonnes in 2010.However, generally catches continue to decline and during recent years (2010–2013) the average annual lobster catches in Oman was approximately 258 tonnes.

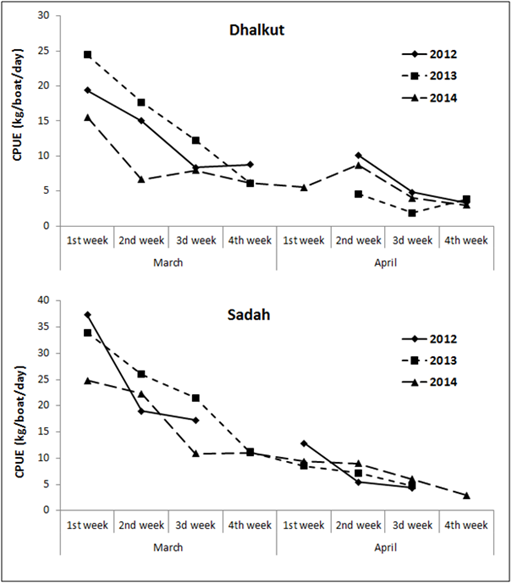

Number of boats operated in the lobster fishery, total daily landings and catch per boat per day (CPUE) were highest at the beginning of the fishing season and then sharply declined (Figure 3). According to our observation, 28–30 boats started work in Dhalkut during the first week of 2012, 2013 and 2014 and total daily landings ranged from 385 to 830 kg, mean daily values for the first week in different years were 543, 685 and 466 kg respectively, mean CPUE fluctuated from 15.5 to 25.5 kg/boat/day. At the end of March, usually 9–12 boats participated in the fishery, the mean daily catches were 61–101 kg in different years, CPUE varied between 6.1 and 8.8 kg/boat/day. At mid-April, only 3–5 boats fished lobsters, total daily landings varied between 10 and 19 kg with CPUE dropped to 2–5 kg/boat/day. The similar picture was observed in Sadah, where 19–21 boats started the season each year and the mean total daily landings ranged from 496 to 747 kg during the first week, mean CPUE reached 24.8–37.4 kg/boat/day. However, at the mid-April only 4–6 boats operated in the fishery with a total daily catch of 19–24 kg and CPUE 4.4–6.0 kg/boat/day respectively. The survey data of 2012–2014 indicate that approximately 86–89% of the total lobster catchin Dhalkut and 72–80% of catch in Sadah were obtained during March, while in April, only 11–14% and 20–28% respectively.

Figure 3 Catch per unit effort in selected landing sites of Dhofar during the open fishing season in 2012-2014.

Size composition

During the study period (2012–2014), the carapace length of P. homarus ranged from 24.2 to 151.3 mm with the mean of 77.3±14.6mm (± Standard Deviation). The weight of the individual lobsters varied from 19.1 to 2686 g and the mean wet weight was 536.9±271.3 g. About 44% of lobsters in commercial catches were larger than minimum legal size (>80 mm CL).The modal size class was 75-80 mm and approximately 1/3 of lobsters were less than 70 mm and 2% of 50 mm. The largest lobster caught was a male from Mirbat in February 2013 that measured 151.27 mm CL with a total weight of 2686 g.

Overall, females were slightly larger and heavier than males. The mean carapace length of females was 78.2±14.8 mm (n=8101), weight 563.9 g (n=3181), while males had 76.2±12.9 mm and 512.2 g. However, 2-tailed t-Test and F-Test for equality of variances, which were used to compare the difference between length means of males and females, indicated that the two sample variances are not significantly different. In some samples, females were larger than males, in the other samples; on the contrary, males were larger than females (Table 1). P values for t-Test and F-test indicated that in most cases the sample variance were not significantly different (at alpha equal to 0.05). Therefore, for further analysis the data for both sexes of P. homarus were pooled.

|

Region |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

||||||

|

F |

M |

P (F-Test ) |

F |

M |

P (F-Test ) |

F |

M |

P (F-Test ) |

||

|

Dhofar Dhalkut |

76.0 (571) |

71.8 (285) |

0 |

74.0 (995) |

73.5 (1153) |

0.28 |

72.4 (408) |

70.7 (454) |

0.06 |

|

|

Mirbat-Hasik |

90.2 (303) |

91.3 (205) |

0.275 |

83.9 (1002) |

86.1 (1088) |

0.422 |

86.2 (1087) |

87.7 (1078) |

0 |

|

|

Al-Wusta |

72.3 (992) |

64.3 (949) |

0.002 |

79.6 (165) |

81.7 (138) |

0.273 |

77.5 (1240) |

72.2 (1243) |

0.445 |

|

|

Sharqiyah |

76.3 (218) |

78.9 (247) |

0.274 |

67.1 (135) |

61.9 (180) |

0.003 |

64.8 (465) |

62.9 (600) |

0.007 |

|

Table 1 Mean carapace length of females (F) and males (M) and P value for the F-ratio indicating differences between variances in different regions from 2012 to 2014

Significant difference between the group variances marked bold.

The size composition of the lobster showed significant variation in different landing sites (Figure 4). Generally, lobsters from Dhofar were significantly larger than those from Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah. During 2012–2014, the mean size of the lobster in Dhofar was 81.6±11.9 mm (n=9454), in Al-Wusta 72.6±12.3 mm (n=4757) and Al-Sharqiyah 67.3±12.2mm (n=1845). The largest lobsters with an average carapace length approximately 90 mm were recorded between Mirbat and Lakbi. Besides, relatively large animals (mean 78–82 mm) were registered in Mahut and around Masirah Island. Medium-sized lobsters (about 75 mm) occurred mainly in waters from Dhalkut to Mirbat and between Lakbi and Ras Madrakah. The smallest lobsters (less than 70 mm) were abundant in the northern part of the species range to the north from Ras Madrakah to Duqm (Al-Wusta) and between Ashkharah and Ruways (Al-Sharqiyah).

No decline in size composition of commercial lobster catches was observed in Dhofar during studied years, the percentage of small illegal-sized specimens(<80 mm CL) was approximately 40% and percentage females with eggs ranged from25.6 to 32.0% (Table 2). However, significant geographical differences were observed in the Dhofar region. While, the mean sizes of lobster in 2012, 2013 and 2014 in southern Dhalkut were 75.2, 74.8 and 71.2 mm respectively, in the northern area between Mirbat and Hasik,it had reached to 91.5, 89.4 and 88.5 mm respectively. The percentages of illegal-sized lobsters contributed 70–82% in commercial landings off Dhalkut and only 10.2–21.1% between Mirbat and Hasik area. In addition, no obvious trend in the mean lobster sizes was observed in Al-Wusta during 2012–2014. Percentage of illegal-sized lobsters here varied in a wide range from 77.3% in 2012 to 56.5% in 2013, the portion of egg-bearing females was lowest (19.1%) in 2014 and reached 30.9% in 2013. In Al-Sharqiyah, a declining trend was observed in the mean lobster length that dropped from 77.7 mm during 2012 to 63.8 mm in 2014. The percentage of the illegal-sized lobster in catches in Al-Sharqiyah was highest, reaching 87.0–90.3% in 2013–2014. Due to dominance of small lobsters in Al-Sharqiyah, the percentage of berried females here was very low (5.8–18.3%). Overall, on the pooled data for three regions, the mean sizes of P. homarus in commercial landings increased from 74.8 mm in 2012 to 78.4 mm in 2013 and 77.8 mm in 2014, resulting decrease the percentage of illegal-sized specimens in catches from 61.6 to 54.2%.

|

Region |

Characteristic |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

Dhofar |

Sampled number |

1571 |

4278 |

3605 |

|

Mean CL (mm) |

82.6 |

82.7 |

82.9 |

|

|

Illegal size <80 mm CL (%) |

42.8 |

43.5 |

39.5 |

|

|

Number of females (%) |

66.1 |

49.3 |

49.6 |

|

|

Egg-bearing females (%) |

32 |

25.6 |

30.1 |

|

|

Al-Wusta |

Sampled number |

1941 |

333 |

2483 |

|

Mean CL (mm) |

68.4 |

80 |

74.5 |

|

|

Illegal size <80 mm CL (%) |

77.3 |

56.5 |

65.4 |

|

|

Number of females (%) |

51.1 |

52.6 |

49.9 |

|

|

Egg-bearing females (%) |

19.3 |

30.9 |

19.1 |

|

|

Al-Sharqiyah |

Sampled number |

465 |

315 |

1065 |

|

Mean CL (mm) |

77.7 |

64.1 |

63.8 |

|

|

Illegal size <80 mm CL (%) |

51 |

87 |

90.3 |

|

|

Number of females (%) |

46.9 |

42.9 |

43.7 |

|

|

Egg-bearing females (%) |

18.3 |

13.3 |

5.8 |

|

|

All data |

Sampled number |

3977 |

4926 |

7153 |

|

Mean CL (mm) |

74.8 |

78.4 |

77.8 |

|

|

Illegal size <80 mm CL (%) |

61.6 |

55.2 |

54.2 |

|

|

Number of females (%) |

56.7 |

47.7 |

48.8 |

|

|

Egg-bearing females (%) |

24.8 |

24.7 |

20.5 |

Table 2 Biological indicators of the lobster P. homarus in different regions of Oman from 2012 to 2014

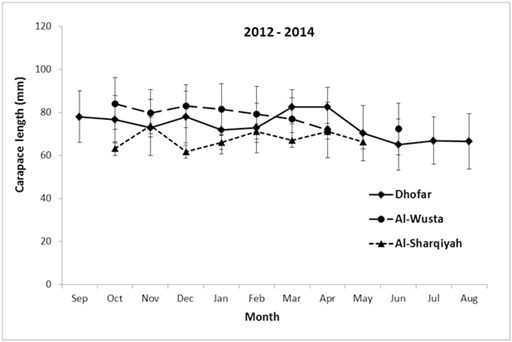

Monthly variation of mean lobster sizes during a year is not well expressed (Figure 5). Pooled data for three years in different regions showed steady decrease of the lobster size in Al-Wusta from October to April, relatively stable situation in Al-Sharqiyah and relatively larger lobsters landed in Dhofar during fishing season (March-April) which then declined in summer period from June to September.

Figure 5 Monthly mean sizes of P. homarus in Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah during a year, on data combined from 2012 to 2014.

Sex ratio

The pooled sex ratio of the P. homarus population in Omani waters was close to 1:1. Females slightly outnumbered males in ratio 1.01:1 (49.8% males and 50.2% females), but some regional and interannual differences were observed (Table 2).

Length at first maturity

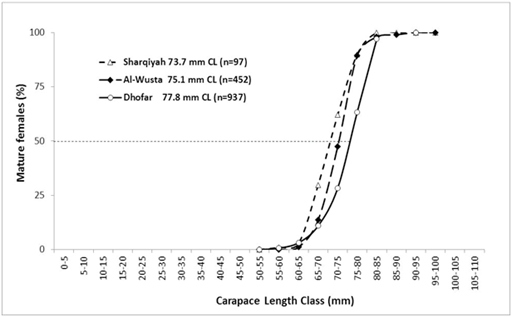

The smallest female carrying eggs in Dhofar in 2012–2014 was 58.7 mm and the female after releasing eggs was 65.94 mm, in Al-Wusta 65.9 and 67.6 mm CL and in Sharqiyah 62.7 and 73.2 mm CL respectively. The length at first maturity estimated using logistic formula was 77.8 mm in Dhofar, 75.1 mm in Al-Wusta and 73.7 mm in Al-Sharqiyah (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Cumulative percentages of egg-bearing and releasing eggs females in length classes and length at first maturity of P. homarus in Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Sharqiyah in 2012-2014.

Breeding cycle

The monthly-pooled data for 2012, 2013 and 2014 in Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Sharqiyah showed the occurrence of more number of egg-bearing females in Al-Wusta during November, December and February, in Sharqiyah during November and in Dhofar with two peaks during September–October and March–May (Figure 7). During the summer monsoon period (June-August), only small-sized immature lobsters were sampled and few females were found carrying eggs. Pooled data for all regions showed more percentage of the egg-bearing females from September until December, declining trend in January-February, then slightly increase in March-May and lowest values occurred in June–August.

Length-weight relationships

A total of 7058 specimens weighed in Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Sharqiyah from 2012 to 2014 were used to calculate relationships between total wet weight and carapace length of the lobster. The L-W equations, obtained in respect to the pooled data, males, females and females with eggs, are presented in Table 3. In all instances, wet weight was strongly correlated with carapace length and has shown negative allometric growth and the coefficient of determination (R2) was higher 0.88. Females have substantially heavier weight than males of the same length, also females with eggs are heavier than females without eggs. ANOVA test showed significant differences between L-W slopes in males and females (F=15.36, P>0.05) and also between other groups, however, as species considered as one stock, the pooled data were used for further stock assessment.

|

Country |

Group |

L-W Equation |

N |

Size Range (CL, Mm) |

Reference |

|

India |

Pooled data |

W = 0.00566 L2.50 |

– |

– |

Meenakumari et al.33 |

|

Somalia |

Males |

W = 0.0022 L2.8031 |

142 |

24–110 |

Fielding & Mann19 |

|

Females |

W = 0.0014 L2.9388 |

129 |

|||

|

Sri Lanka |

Males |

W = 0.0015 L2.71 |

– |

– |

Sanders & Liyanage32 |

|

Females |

W = 0.0022 L2.54 |

||||

|

Oman |

Pooled data |

W = 0.0018 L2.7733 |

157 |

37.7–100.6 |

Al-Marzouqi et al.5 |

|

Males |

W = 0.003 L2.629 |

75 |

37.7–100.6 |

||

|

Females |

W = 0.0024 L2.7117 |

82 |

52.5–100.2 |

||

|

Oman |

Pooled data |

W = 0.0017 L2.8812 |

7058 |

24.2–151.3 |

Present study |

|

Males |

W = 0.0018 L2.8597 |

3617 |

28.9–151.3 |

||

|

Females |

W = 0.0016 L2.9124 |

3440 |

24.2–131.8 |

||

|

Egg-bearing |

W = 0.0054 L2.6397 |

848 |

60.6–121.7 |

Table 3 Length-weight relationships of P. homarusfrom various locations in the Western Indian Ocean

Growth parameters and age composition

Remarkable differences were obtained in values of the asymptotic length (Linf) for different regions that were estimated as 114.3 mm in Al-Sharqiyah, 128.0 mm in Al-Wusta and 141.5 mm in Dhofar, whereas the growth coefficient (K) has more compatible values and ranged between 0.36 and 0.42 yr-1(Table 4). Initial age at zero length (to) was estimated between –0.13 and –0.32 yr.

|

Country |

Method |

Linf |

K |

to |

Reference |

|

India |

Tagging |

♂312TL |

0.72 |

-0.09 |

Mohammed & George20 |

|

♀303TL |

0.6 |

-0.12 |

|||

|

Kenya |

Grow-out |

♂115 |

0.25 |

- |

Kulmiye & Mavuti22 |

|

♀105 |

0.29 |

||||

|

South Africa |

LFDA |

♂120 |

0.18 |

- |

Smale34 |

|

♀94.2 |

0.34 |

||||

|

Somalia |

LFDA |

♂127 |

0.46 |

-0.61 |

Fielding & Mann19 |

|

♀110 |

0.44 |

-0.53 |

|||

|

Sri Lanka |

LFDA |

287 TL |

0.43 |

0.38 |

Jayaweckrema31 |

|

Sri Lanka |

LFDA |

♂127 |

0.41 |

- |

Jayakody35 |

|

♀121 |

0.39 |

||||

|

Sri Lanka |

LFDA |

♂134 |

0.51 |

- |

Sanders & Liyanage32 |

|

♀130 |

0.48 |

||||

|

Yemen |

LFDA |

♂136 |

0.46 |

- |

Sanders & Bouhlel29 |

|

♀118 |

0.44 |

||||

|

Oman |

LFDA |

128.9 |

0.33 |

-0.35 |

Al-Marzouqi et al.5 |

|

Oman |

LFDA |

♂146.8 |

0.72 |

- |

Mehanna et al.6 |

|

♀136.5 |

0.77 |

||||

|

143.2 |

0.71 |

||||

|

Oman |

LFDA |

- |

- |

- |

Present study |

|

Dhofar |

141.5 |

0.36 |

-0.13 |

||

|

Al-Wusta |

128 |

0.42 |

-0.32 |

||

|

Al-Sharqiyah |

114.3 |

0.38 |

-0.22 |

Table 4 Parameters of von Bertalanffy growth function of P. homarus estimated in various locations in the Western Indian Ocean

Lobsters from 0 to 10 year old were found in catches of Dhofar. The dominant age group appears to be between 1and 3 years and the mean age was calculated as 2.12 in 2012, 1.99 in 2013 and 2.23 years in 2014. In Al-Wusta, the lobsters support the fishery up to the age of 9 years. The 1–2 year old lobsters were more common in catches and the mean age was 1.42, 2.01 and 1.73 years in 2012, 2013 and 2014 respectively. The age distribution in catches in Al-Sharqiyah region indicated that lobsters of 0−8 years occurred and the dominant age group was 1–3 years, the mean age in 2012 was 2.02 year and 1.80−1.83 years in 2013−2014 respectively.

Mortality and exploitation rates

The coefficient of total mortality (Z) had higher values in Al-Wustathan those in Al-Sharqiyah and Dhofar. The mean values for these regions pooled for the studied three years were 2.03, 1.97 and 1.80 yr-1 respectively (Table 5). The average Z value for all data combined in different years (2012 to 2014) and regions was 1.88 yr-1. The estimated values of natural mortality (M) ranged between 0.58 and 0.65 yr-1 and were higher in Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah than in Dhofar. The annual fishing mortality rate (F) varied between 1.17 and 1.40 yr-1 and it was higher in Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah, the average value pooled from different years and regions was 1.23 yr-1. The exploitation rate (E) ranged between 0.66 and 0.69 in Dhofar and Al-Wusta and 0.65–0.66 in Al-Sharqiyah.

|

Parameter/ Region |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

All Data 2012–2014 |

|

Total Mortality (Z) |

||||

|

Dhofar |

1.75 |

1.85 |

1.71 |

1.8 |

|

Al-Wusta |

2.03 |

1.86 |

1.96 |

1.93 |

|

Al-Sharqiyah |

1.84 |

1.9 |

1.82 |

1.87 |

|

Pooled data |

1.88 |

1.87 |

1.83 |

1.85 |

|

Natural Mortality (M) |

||||

|

Dhofar |

0.58 |

0.58 |

0.58 |

0.58 |

|

Al-Wusta |

0.63 |

0.63 |

0.63 |

0.63 |

|

Al-Sharqiyah |

0.64 |

0.64 |

0.64 |

0.64 |

|

Pooled data |

0.62 |

0.62 |

0.62 |

0.62 |

|

Fishing Mortality (F) |

||||

|

Dhofar |

1.17 |

1.27 |

1.13 |

1.22 |

|

Al-Wusta |

1.4 |

1.23 |

1.33 |

1.3 |

|

Al-Sharqiyah |

1.2 |

1.26 |

1.18 |

1.23 |

|

Pooled data |

1.26 |

1.25 |

1.21 |

1.23 |

|

Exploitation Rate (E) |

||||

|

Dhofar |

0.67 |

0.69 |

0.66 |

0.68 |

|

Al-Wusta |

0.69 |

0.66 |

0.68 |

0.67 |

|

Al-Sharqiyah |

0.65 |

0.66 |

0.65 |

0.66 |

|

Pooled data |

0.67 |

0.67 |

0.66 |

0.66 |

Table 5 Mortalities and exploitation rate of P. homarus in different regions of Oman during 2012–2014

Yield per recruit analysis

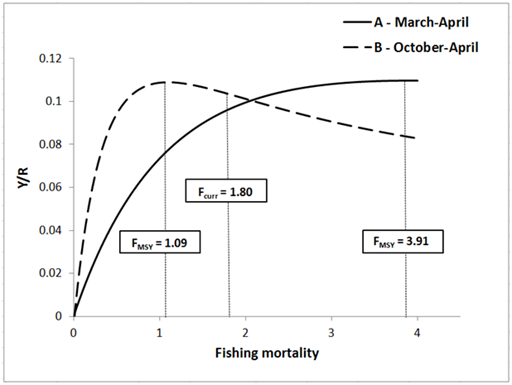

The Y/R analysis was conducted separately for the 2-month fishing season (March–April) and for the 7-month season (October–April), assuming illegal fishery out of the open fishing season. By testing various F-values, it was found that the maximum Y/R in Dhofar at the 2-month fishing season was at F equal to 3.91 yr-1, equilibrium MSY was 2.01 and F0.1 was 2.19 yr-1 (Table 6, Figure 8A). However, if the calculations based on the 7-month fishing season, then the reference point values decreased significantly. So, the Y/R curve in Dhofar reached the maximum value at FMSY equal to 1.09 yr-1, equilibrium MSY at 0.58 yr-1and F0.1 at 0.63 yr-1 (Figure 8B). Similar picture was observed in Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah. It was calculated that to achieve the FMSY, the lobster catches should be in a range of 32.2–39.3% of the total biomass. The projection however will change Y/R reference points in a case of a shift of the 2-month fishing season to one month during a year, shown that the maximum values of FMSY and others gradually increased from October-November to April-May, then the values sharply decreased and minimum were in June-July.

Figure 8 Yield per recruit (Y/R) vs. fishing mortality rates for P. homarus in Dhofar at different fishing seasons.

|

Reference Point |

March–April |

October–April |

||||

|

Dhofar |

Al-Wusta |

Al-Sharqiyah |

Dhofar |

Al-Wusta |

Al-Sharqiyah |

|

|

FMSY |

3.91 |

6.03 |

5.10 |

1.09 |

1.27 |

1.75 |

|

F0.1 |

2.19 |

2.81 |

2.59 |

0.63 |

0.71 |

0.84 |

|

Equilibrium FMSY |

2.01 |

2.51 |

2.06 |

0.58 |

0.64 |

0.68 |

|

Yield-per-R /FishBo (%) |

15.4 |

20.6 |

18.1 |

15.5 |

18.2 |

20.4 |

|

SSB-per-R / SSBo (%) |

15.2 |

9.8 |

8.3 |

16.8 |

13.4 |

8.2 |

|

Total B-per-R / Total Bo (%) |

24.6 |

22.3 |

23.4 |

25.9 |

24.4 |

25.4 |

|

Catch / Total biomass (%) |

32.7 |

39.7 |

32.8 |

32.2 |

36.9 |

34.0 |

Table 6 Some biological reference points in yield-per-recruit analysis in different regions of Oman at 2-month and 7-month fishing seasons

Official statistical data show a steady decline in lobster landings in Oman, despitea number of management measures, implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The mean value of the landing for the 2010–2013 period, after introduction of the new fishing season (March–April) was 258 tonnes, while previously during 2003–2008 in the 15 October, 15 December fishing season, the mean was about 333 tonnes. However, the official statistics significantly underestimated actual catch as traders do not register all landings and fishers sometimes use lobster as food for families, friends, or sell directly to some restaurants, poaching out of season is also very common. Some fishers are catching lobsters throughout October to April with nets as so-called "by catch". Expert estimates made in 2002 state that the export of illegally caught Omani lobsters (mainly to Dubai) annually reached 850 tonnes, approximately three times more than the ‘official’ landings.15s In Al-Marzouqi et al.5 the unreported catch is approximately equal to reported catch. Therefore, it can be assumed that current annual catches can reach approximately 500 tonnes of shallow water lobster for the Arabian Sea coast of Oman.

Considerable difficulties were experienced in obtaining meaningful unit of fishing effort data for the Omani lobster fisheries due to hundreds or even thousands of boats and the large fishing area extending about 1200 km from the border with Yemen to Ras-al-Hadd and around Masirah Island. Numbers of boats and crews engaged in the lobster fishery changed almost every day. Generally, landings and number of boats operating in the lobster fishery tended to be highest at the beginning of each season and then sharply drop. Based on our calculation, the CPUE ranged between 15–37 kg/ boat/ day in different sites of Dhofar during the first week of March, when dozens boats in different sites caught hundreds kilos of lobsters, whereas to the end of season in April the CPUE declined to 2–6 kg/boat/day, because usually 2–6 boats worked on the lobster fishery in a site with mean total daily catch of 10–24 kg. Only 11–28% of the total landing were obtained in April, therefore it is possible to decrease fishing season to one month or 45 days without significant loss of the catch.

In the present study, mean lobster sizes increased in Dhofar and Al-Wusta during 2012–2014 in comparison with data of Al-Marzouqi et al.5 collected during 2003–2005: Dhofar from 77.0 to 81.6 mm, Al-Wusta from 69.8 to 72.6 mm. Similarly, the maximum registered CL in 2003–2005 was 116.6 mm in Al-Wusta and 127.7 mm in Dhofar, which had reached 132.7 and 151.3 mm respectively during the present study. The lobster of 151.3 mm CL with 2686 g found in Mirbat in February 2013 appears to be the largest P. homarus currently recorded in the world, because previously known maximum size was 120 mm CL16 and 140 mm CL.1 As lobster size increased, correspondingly the percentage of illegal-sized animals in catches decreased: Dhalkut from 68% during 2003–2005 to 56% in 2012–2014; Dhofar from 65 to 45% respectively. The increase in lobster sizes would be an important positive biological response due to the change of the fishing season from 15 October – 15 December to March–April.

There were clear geographic differences in mean lobster sizes in different landing sites of Oman.3,5 In our data, the geographical variation in body size of the P. homarus was observed from Dhalkut near border of Yemen to Ashkharah in Al-Sharqiyah region (Figure 3). The larger lobsters, with mean carapace length approximately 10 mm larger than in other sites, occurred in the area between Mirbat and Lakbi. The geographical differences in the lobster sizes are likely due to differences in oceanographic conditions, habitats, such as availability of shelter and benthic productivity besides intensity of fishery exploitation. Generally, lobsters tend to be larger in rocky areas, while in flat sandy habitats individuals usually are small and medium size. Geographical variation in lobster size causes problem of management of the lobster fishery in Oman to consider as a unit stock having uniform biological traits. Hence, minimum legal size (>80 mm CL) of the lobster that is applied across the entire Oman coast for some landing sites appears not appropriate. During 2012–2014 the percentages of illegal-sized lobsters in Dhalkut was about 70–80%, between Mirbat and Sharbithat 13–28%, while in Al-Wusta 56–77% and in Al-Sharqiyah reached 87–90%.Therefore, various forms of spatial-temporal management may be considered including regional size limits.

The highest proportion of females, 66% was found in Dhofar during the 2012 fishing season might increases the reproductive potential of the population is a favorable factor. However, the pooled sex ratio for Dhofar and Al-Wusta regions for 2012–2014 was equal (0.50:0.50) similar to the earlier observation5 indicating that the shift of the fishing season did not affect the population sex ratio along the Oman coast.

The length at first maturity, found in this study equal to 77.8, 75.1 and 73.7 mm in Dhofar, Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah respectively, is much larger than that reported by Al-Marzouqi et al.5 for 2003–2005 as 63.9 mm in Al-Wusta and 65.6 mm in Dhofar. Female lobsters with larger carapace length made the greater contributions to egg production,17 because of their high brood size and higher reproductive activity, which also increase the chances of successful recruitment. The difference in size of maturity can result from biotic and abiotic environmental variables (population density, temperature, food availability, shelters, etc.) and anthropogenic factors (exploitation rate). It can also be a positive outcome of the Ministry’s decision related to the change in the lobster-fishing season and decrease of fishing pressure on the berried females.

According to current management regulations, it is prohibited to take egg-bearing females, therefore the detection of the period with most numbers of berried females is important for fisheries management. It is known that the spiny lobster P. homarus is a continuous breeder and females may carry eggs throughout theyear.18 Johnson & Al-Abdulsalaam2 found berried females during all months from September to February 1987–1990. They found 50% of the females carried eggs in Sharqiyah in October–November, in central Dhofar the peak was in December and January, in south Dhofar the peak extended to February. Al-Marzouqi et al.7,8. reported a prolonged reproductive season with two peaks for the egg-bearing females in October–November and May–June and the low number from February to April and no geographical gradient in egg-bearing seasonality was observed. During the present study, though, egg-bearing females of P. homarus occurred in all months, very low numbers were found during the monsoon period (June-August) and the main peak was recorded from September to December. The shift of the fishing season to March–April appeared to protect the egg production potential of the lobster population. As the percentage of the egg-bearing females varied among regions, regional approach for the open lobster season may be considered.

Literature data on length-weight relationships of P. homarus from various waters were mostly based on a small number of measurements and small size range (Table 3). Our results on the length-weight relationships are similar to those along the Somalia coast.19 In the present study, the weight of the Omani lobster appears to be slightly heavier for the given than length (F=16.2, P>0.05) reported in the previous study.5

In many growth studies based on length frequency distribution at year round reproduction of the species, the cohorts or year classes are indistinguishable. The descriptions of growth of P. homarus using a tagging method20 or grow-out data21-28 are rare and assessed growth only during a short period of the lobster life. The growth parameters especially the in VBGF estimated in the present study (Table 3) especially the asymptotic lengths (Linf) for Al-Wusta and Al-Sharqiyah concur with majority of authors. However, in Dhofar specimens recorded were significantly larger in size than in other areas. The growth coefficient (K) for P. homarus, estimated in studies in Yemen, Sri Lanka and Somalia, varies between 0.39 and 0.51 yr-1.19,29-32 In Oman, according to the present study, the K values ranged of 0.36–0.42 yr-1, which is a little higher than 0.33 yr-1 on results of Al-Marzouqi et al.,5 but significantly lower than 0.71–0.77 yr-1reported by Mehanna et al.6

Though, the age estimations indicated the occurrence of lobsters of 0 to 10 years of age in the commercial catches, the dominant age groups were between 1and 3 years. It appears that the lobster is recruited to the fishery at one year of age at lengths of around 45–50 mm of CL. The specimens contributed to the catch for another year has reached lengths of about 75–80 mm, older lobsters were negligible in the landings. This finding suggests high levels of exploitation.

The mortality coefficients and exploitation rate obtained in the present study were compared with estimates from other works (Table 7). The total mortality (Z) estimate agreed with Al-Marzouqi et al.;5 however, it was lower than reported by Mehanna et al.6 and off Yemen,29 Somalia19 and Sri Lanka.30 The natural mortality (M) compares well with many other estimates, excluding values of Jakody30 and Mehanna et al.6 The exploitation rates (E) obtained in the present study (0.65–0.69)are slightly higher than 0.52–0.68 estimated by Al-Marzouqi et al.;5 however, notably lower than reported by Mehanna et al.6 The values of total mortality, fishing mortality and exploitation rate estimated by Mehanna et al.6 seems to be very high for Omani waters. However, present study also shows high values of both fishing mortality and exploitation rate suggesting an intensive exploitation of the species along the Arabian Sea coast of Oman. Unfortunately, the shift of the fishing season did not reduce the fishing pressure on the population that remains higher than the optimum level.

|

Country |

Z |

M |

F |

E |

Reference |

|

Yemen |

♂2.33 |

0.63-1.44 |

1.25 |

0.6 |

Sanders & Bouhlel29 |

|

♀2.04 |

-0.85 |

||||

|

2.1 |

|||||

|

Somalia |

♂2.70 |

0.6-0.85 |

1.0-2.1 |

0.37-0.78 |

Fielding & Mann19 |

|

♀1.84 |

|||||

|

Sri Lanka |

1.08 |

1.04 |

0.04* |

0.04 |

Jayaweckrema31 |

|

Sri Lanka |

♂2.10 |

0.98 |

1.12* |

0.53 |

Jakody30 |

|

♀1.60 |

0.92 |

0.68* |

0.43 |

||

|

Sri Lanka |

- |

♂0.76 |

- |

- |

Sanders & Liyanage32 |

|

♀0.73 |

|||||

|

Oman |

1.49-2.21 (1.86) |

0.59-0.89 |

0.97-1.27 |

0.52-0.68 |

Al-Marzouqi et al.5 |

|

2003–2005 |

|||||

|

Oman |

♂4.11 |

0.95 |

3.16 |

0.78 |

Mehanna et al.6 |

|

2011–2012 |

♀4.76 |

0.95 |

3.81 |

0.8 |

|

|

Oman |

1.71-2.03 |

0.58–0.64 |

1.17-1.40 |

0.65-0.69 |

Present study |

|

2013–2014 |

-1.85 |

-0.62 |

-1.23 |

Table 7 Mortalities and exploitation rate of P. homarus in different regions of the Western Indian Ocean

The yield-per-recruit analysis indicates that the current level of fishing mortality (Fcurr = 1.22–1.30 yr-1) appeared lower than that given by the maximum Y/R (FMSY = 3.91–6.03 yr-1) during the2-month fishing season. However, if we take into account illegal fisheries out of the season, which may last7 months (October–April), the estimations of FMSY and other conservative reference points (equilibrium FMSY and F0.1) are close to Fcurr or notably lower. In this case, the lobster stock appears to be overfished The Y/R would be higher, if lobsters landed have reached 70–80 mm CL, instead of being captured once they reach 40–50 mm CL. Therefore, optimization of the lobster fishery cannot be achieved only through reduction of the fishing effort; strict implementation of all current fishing regulations is also required.

The present study shows that the change of the fishing season from 15 October-15 December to 1 March – 30 April in 2010 had several positive effects on the biological structure of the lobster population. During recent years (2012–2014), compared to 2003–2005, the mean lobster size in landings increased significantly and at the same time, there was a decrease in the percentages of undersized animals and egg-bearing females and also an increase in the size at first sexual maturity. These are positive indicators of improvement for the lobster fishing stock. However, lobster landings continue to decline gradually due to the violation of the fishing regulations. The strict enforcement of the current regulations is not possible without a special legislative system. The implementation of a licensing system will decrease the number of lobstermen and the fishing effort and promote more control from officials and self-control of fishery communities. Furthermore, it is recommended to encourage private and government companies to increase the purchase price of the lobster and discouraging traders to buy small lobsters and egg-berried females. As additional measures to protect and rebuild the lobster stock, we suggest to consider various forms of spatial-temporal management, including regional size limits, different fishing season periods and regional quota system. Apart from the regulation of the fishery, there are other approaches, such as stock recovery and production enhancement by means of organizing protected areas, construction of special artificial reefs, collection of undersized lobsters and their grow-out in sea cages. The strategy for managing the Omani lobster fishery should also take into account of socio-economic and ecological aspects. Local fishing communities should be made aware of the adverse effects of overfishing their fishing grounds. Co-operation and co-management among fishers, scientists and government officials is very important for implementing sustainable development of the lobster fishery in Oman.

None.

None.

©2015 Al-Marzouqi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.