Journal of

eISSN: 2378-3184

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

Department of Marine Science Mawlamyine University Myanmar

Correspondence: Naung Naung Oo Assistant Lecturer Department of Marine Science Mawlamyine University Myanmar

Received: May 09, 2018 | Published: May 25, 2018

Citation: Naung NO. Top shells of Andrew Bay in Rakhine coastal region of Myanmar with notes on habitat, local distribution and utilization. J Aquac Mar Biol. 2018;7(3):127?133 DOI: 10.15406/jamb.2018.07.00198

Top shells on intertidal and subtidal areas of Andrew Bay in Rakhine Coastal Region of Myanmar are composed of 2 species of genus Monodonta Lamarck, 1799; 2 species of genus Tectus Montfort, 1810; 6 species of genus Trochus Linnaeus, 1758 and 2 species of genus Umbonium Link, 1807 belonging to family Trochidae Rafinesque, 1815 falling under the order Archaeogastropoda Thiele, 1925 collected from field observation during 2005-2017, were identified, using liquid-preserved materials and living specimens in the field, based on the external characters of shell structures. The collected specimens comprised Monodonta labio (Linnaeus, 1758) and M. canalifera Lamarck, 1816; Tectus fenestratus (Gmelin, 1791) and T. pyramis (Born, 1778); Trochus conus Gmelin, 1791, T. maculatus Linnaeus, 1758, T. niloticus Linnaeus, 1767, T. radiatus Gmelin, 1791, T. triserialis Lamarck, 1822 and T. erithreus Brocchi, 1821; Umbonium vestiarium (Linnaeus, 1758) and U. costatum (Kiener, 1838). The distribution of top shells in intertidal and subtidal zone of Andrew Bay was studied in brief. Moreover, the habitats and utilization, comparison of some conchological features and the ecological aspects of top shells around the Andrew Bay were described.

Keywords: Top shells, Trochidae, conchological features, ecological aspects, Andrew Bay, Rakhine Coastal Region, Myanmar

Andrew Bay in Rakhine Coastal Region of Myanmar is rich ground for a variety of commercially important molluscs. Among the sea shells, monodonts and trochid or top shell occupy a unique position for their utility and abundance. Marine benthic organisms often exhibit distinct pattern in distribution throughout their geographical range, which were evidence in both spatial as well as temporal scale.1 The patterns of distribution were largely determined by the habitat characteristics, which include the physical, as well as the biological environments in Myanmar coastal water. Combinations of physical and biological characteristics were generally involved where in most occasions not one factor alone can explain the distributional patterns of a species. Determination of these factors and how organisms react when changes in environmental condition occurs, are very important for management of the marine resources.2 Gastropods from the family Trochidae are group of commercially important marine snails, which occurred throughout the tropical and subtropical regions.3 The variety of seashells in Myanmar is mentioned in even the oldest reports of the first explorers.4 Monodonts and trochids are one of the most diverse group of marine gastropods in Rakine Coastal Region. Some authors have reported significant variations in spatial and temporal distribution and abundance of some species within this family.4‒12 Much information such as their distribution pattern, habitat preferences and habitat range were still remained unknown.

The objectives of current study are 1) to identify the diversified species of top shells; and 2) to investigate the species distribution of top shell population in their natural habit. This information is very important for conservation and for better management of top shell species.

Some top shells were collected in the forms of drift and live specimens living in intertidal and shallow subtidal areas such as Geik Taw, Pearl I, Thanban Gyaing, Abae Chaung, Thanbayar Gyaing, Mayoe Bay, Kathit I, Thabyu Gyaing, Ponenyat Gyaing, Kwinwine Gyaing, Kyauk pone gyi hmaw and Maung shwe lay Gyaing around the Andrew Bay (Lat. 18º 25′ N, Long. 94º 15′ E), Rakhine State (Figure 1) during the field trip in 2014. All collections were preserved in 10 % formalin in seawater. The epifaun as were removed by soaking the shells in a solution of caustic soda and then cleaned, washed, dried, and ready for storage, they are lightly rubbed with a small amount of oil applied with a brush to make them fresh-looking in a slight luster to the surface, and aid in presenting the delicate colouring for further study. All voucher specimens were deposited at the Museum of the Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University (MLM.MS). Zoogeographical distribution of each species was prepared with the data from the literature available. Ecological notes and associated species of these molluscs were also recorded in the field.

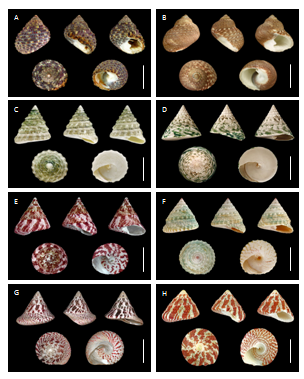

Totally 12 species of top shells from different habitats of coral reef, rocky shore and fine sandy bottom found along the intertidal zone of Andrew Bay in Rakhine Coastal Region of Myanmar. This systematic account follows the identifying set out by Morris et al. in detailed12‒27 (Table 1) (Figure 2).

The family Trochidae is a moderately diverse group mostly found at littoral and shallow sublittoral, occurring in large numbers on hard substrates like rocky shores or coral reefs.28 However, there are also species living among seagrass or on deep-water bottoms of sand or mud (Table 2) (Table 4). Slow moving animals, browsing on detritus and algae, sometimes filter-feeding (genus Umbonium). Larger or most common species of Trochidae are traditionally used as food by coastal populations in Southeast Asia and oceanic islands of the Southwest Pacific.3 Shells are utilized by the shell craft industries and food, sometimes serving as mother-of-pearl or as lime material in Myanmar (Table 5). The distribution of many trochids species extend northwards to Central deltaic, and to southern parts of Taninthayi. In order to undertake a biogeographic study on the distribution a comprehensive species-distribution table was compiled for the Andrew Bay top shells, comprising 2 species of Monodonts, 8 species of Trochids, and 2 species of Umbonics (Table 3).

The present study has provided qualitative and quantitative information on distribution patterns of top shells around the Andrew Bay regions. No previous study has provided detailed description of distribution patterns, habitats, utilization and identification of top shells on intertidal to subtidal water in this region. Few studies have been done on intertidal seashells survey since many years ago. Soe Thu6 reported 46 species of marine molluscs on intertidal water at Ngapali and also found that the distribution, habitats and local utilization of each species was considerable to ecological aspects. Members of the family Trochidae are also widely distributed in Myanmar water with high frequency. Out of the three genera that occurred, Umbonium is very abundant in Gwa area along the Rakhine Coastal Region, but rare in other areas. However, the members of the family range to Indo-West Pacific, from Madagascar to Micronesia; from East Africa to Melanesia; from Sri Lanka to western Polynesia; from India to the Philippines; from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan Province of China to the Philippines; north to southern Japan, and south to Indonesia; north to Japan and south to Queensland and New Caledonia.3,29,30

Characteristics of family trochidae: Shell pyramidal, conical to globose in shape, with a moderately large, rounded to angular body whorl and often with a flattened base. Umbilicus more or less narrow to closed, sometimes with a calloused plug. Outer surface smooth or sculptured axially and spirally, with beads, nodules, or tubercles. Periostracum sometimes conspicuous. Aperture rounded to squarish, without a siphonal canal, nacreous inside. Columella and margin of the outer lip generally not in the same plane (Table 6). Operculum corneous, nearly circular, with many coils and a central nucleus. Head with a short snout, a pair of conical, often papillate tentacles and cup-shaped, open eyes on distinct stalks. Foot moderately small, often medially grooved, with a large fleshy ridge on either side bearing sensitive tentaculate processes.

Characteristics of monodonts: The very heavy in shell construction, thick, solid shell has a turbinate-conic or globular shape. The shell is smooth or surface beaded and spirally ridged. Apex is slightly pointed and the last body whorl is inflated (Table 6). The outer lip is plicate within. The short, porcellanous columella is strong, cylindrical, bulging or more or less toothed near or at the base. Between this tooth and the basal margin there is a square notch or channel. The aperture is as high as wide and nacreous.

Characteristics of tectids: Shell large, conical in shape, about as wide as long or slightly longer. Spire tall, with pointed apex, flat-sided whorls and reduced sculpture usually weakening with growth and becoming obsolete on body whorl of large specimens. Umbilicus absent (Table 6). Aperture squarish in outline. Outer lip markedly angulated at periphery and strongly oblique above, nearly smooth inside apart from a few short spiral grooves near columella, corresponding with the outer sculpture of base. Columella with a strong, concave spiral fold.

Characteristics of Trochids: Shell large, thick and very heavy, conical in shape, about as long as wide (Table 6). Spire tall, with pointed apex and shallow sculpture, weakening with growth and disappearing on later whorls. Umbilicus present, partly filled with a spiral ridge of columella. Periostracum fibrous, enhancing the strongly oblique incremental lines, usually rubbed off from upper part of the spire. Aperture squarish, broader than high. Outer lip strongly oblique above periphery, smooth inside. Columella long, curved and smooth, somewhat thickened marginally, ending abruptly in an obtuse anterior knob.

Characteristics of Umbonic: Shell small, lenticular in shape, much wider than long. Spire low, with faintly convex, somewhat embracing whorls and shallowly incised suture. Periphery of body whorl regularly rounded. Base of shell flattened, with a very large, smooth callus plug filling completely the umbilicus. Entire surface of shell smooth and polished, devoid of concentric grooves on the spire whorls. Outer lip of the aperture sharp, smooth inside. Columella smooth, strongly curved anteriorly (Table 6).

Andrew Bay environments are high biologically diverse of marine and estuarine ecosystems in Rakhine Coastal Region but are being degraded region-wide by human activities potentially leading to numerous extinctions. Trochidae is most common of the molluscan fauna of intertidal water in the Indo-West Pacific area and in the past their identification has been problematic.31 These shells play important role in coastal ecosystem. In general, the molluscan fauna of Myanmar is not well known and so a study of this kind is necessary. In this study, 1867 individuals of seashell of which 78 individuals of top shells collected from random sampling at different habitats in Andrew Bay areas (Table 2-4). Top shells lives on muddy-sandy substrata in intertidal and supra-tidal estuarine habitats, coral reef slope, sandy bottom and seagrass beds. Although most top shells are immersed in water during very high tides, adults tend to stay subtidal bottom about 5-10 meters at low water mark and may be found almost a meter above the high tide zone where they lie beneath or crawl up the vegetation bordering the water.

Thanbyar Gyaing was highest abundance and Geik Taw, Pearl I, Thanban Gyaing, Thabyu Gyaing, Ponenyat Gyaing, Kwinwine Gyaing and Kyauk pone gyi hmaw, and Abae Chaung were the second and third abundance, respectively (Table 2). In study areas, top shells had a wide tolerance to temperature, salinity and desiccation. Salinity is normally 33‰ but varies considerably during the year due to periods of heavy rainfall. The entire 12 study sites are rich in detritus and microalgae that form a flocculent mass at the water-substratum interface. Many species of top shells are found around the bay and inlet water which have great variety of environments provide suitable habitats for molluscs with diverse ecological requirements. Many are the utilizable molluscs which occur in fresh water, salt water and terrestrial habitats, but those found in marine and brackish water environs are particularly plentiful and are put to divergent uses.32‒33 In Andrew Bay regions, top shells are harvested for different reasons: for human consumption, for bait, especially in line fishing, for feeding animals, and even for fertilizer. Their shells are used for the production of worked shell pieces for decoration, or for tools and last not least for lime-burning or in the form of meal as admixture to feeding stuffs (Table 5). These different uses have some influence on the fishing methods concerning the quantities to be caught and especially whether the shells have to be unbroken or not.

Figure 2 (A–H) Top Shell: (A) Monodonta labio (Linnaeus, 1758), (B) M. canalifera Lamarck, 1816, (C) Tectus fenestratus (Gmelin, 1791), (D) T. pyramis (Born, 1778), (E) Trochus conus Gmelin, 1791, (F) T. maculatus Linnaeus, 1758, (G) T. niloticus Linnaeus, 1767, (H) T. radiatus Gmelin, 1791. Scale bars=10 cm.

Phylum: Mollusca Linnaeus, 1758 |

||

Class: Gastropoda Cuvier, 1795 |

||

Order: Archaeogastropoda Thiele, 1925 |

||

Family: Trochidae Rafinesque, 1815 |

||

Genus: Monodonta Lamarck, 1799 |

||

M. labio (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Labio Monodont |

Ngwe-nar-jae |

M. canalifera Lamarck, 1816 |

Canal Monodont |

Ngwe-nar-jae |

Genus: Tectus Montfort, 1810 |

||

T. fenestratus (Gmelin, 1791) |

Latticed Top |

Baung-gyi |

T. pyramis (Born, 1778) |

Pyramid Top |

Baung-gyi |

Genus: Trochus Linnaeus, 1758 |

||

T. conus Gmelin, 1791 |

Cone-shaped Top |

Baung-lay |

T. maculatus Linnaeus, 1758 |

Maculated Top |

Baung-lay |

T. niloticus Linnaeus, 1767 |

Commercial Top |

Baung-lay |

T. radiatus Gmelin, 1791 |

Radiate Top |

Baung-lay |

T. triserialis Lamarck, 1822 |

Serial Top |

Baung-lay |

T. erithreus Brocchi, 1821 |

Red Top |

Baung-lay |

Genus: Umbonium Link, 1807 |

||

U. vestiarium (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Common Button Top |

Kyal-thee-kha-yu |

U. costatum (Kiener, 1838) |

Costate Button Top |

Kyal-thee-kha-yu |

Table 1 Systematic of Top Shells in Andrew Bay, Rakhine Coastal Region

Sampling site |

Habitat |

No. of shells |

Geik Taw |

rocky intertidal, sand with seagrass |

193/7 |

Pearl I. |

rocky intertidal, coral patches |

160/7 |

Thanban Gyaing |

sand between coral patches |

178/7 |

Abae Chaung |

muddy sand, mangrove-channel |

121/3 |

Thanbayar Gyaing |

muddy sand with seagrass |

194/8 |

Mayoe Bay |

muddy sand with seagrass |

184/6 |

Kathit I. |

rocky intertidal, reef slope |

135/4 |

Thabyu Gyaing |

sand with seagrass, reef slope |

146/7 |

Ponenyat Gyaing |

sand on rocky intertidal, reef slope |

128/7 |

Kwinwine Gyaing |

sand on rocky intertidal, seagrass |

103/7 |

Kyauk pone gyi hmaw |

sand on rocky intertidal, seagrass |

155/7 |

Maung shwe lay Gyaing |

sand on rocky intertidal, seagrass |

170/8 |

Table 2 Habitat of sampling site in Andrew Bay, Rakhine Coastal Region.

Sampling site |

Recorded species |

|||||||||||

M. labio |

M. canalifera |

T. fenestratus |

T. pyramis |

T. conus |

T. maculatus |

T. niloticus |

T. radiatus |

T. triserialis |

T. erithreus |

U. vestiarium |

U. costatum |

|

Geik Taw |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pearl I. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thanban Gyaing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abae Chaung |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thanbayar Gyaing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mayoe Bay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kathit I. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thabyu Gyaing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ponenyat Gyaing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kwinwine Gyaing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kyauk pone gyi hmaw |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maung shwe lay Gyaing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3 Distribution of top shells in Andrew Bay, Rakhine Coastal Region.

Species |

Habitat |

Monodonta labio |

On rocks and coral reefs. From high in the intertidal zone to shallow subtidal depths |

M. canalifera |

Sand between coral patches, sand from the reef slope, coral carpet with a faviid association, Millepora fringing reef, rock bottom |

Tectus fenestratus |

On rocky shores, usually in muddy areas |

T. pyramis |

Abundant in coral reef and rocky shore habitats. Littoral and shallow subtidal zones to a depth of about 10 m |

Trochus conus |

Near coral reefs, on subtidal bottoms to a depth of 5 m |

T. maculatus |

Common in coral reefs and rocky shores, from low in the intertidal zone to a depth of about 10 m |

T. niloticus |

In coral reef areas, typically in shallow, high-energy portions of barrier and fringing reefs. Feeds on filamentous algae and generally avoids bottoms of sand and living corals. Densities of populations generally decreasing in deeper areas, while the mean size of individuals increases. Rarely occurring beyond a depth of 10 m |

T. radiatus |

Shells occurred in sand between coral patches, sand with seagrass and mostly in sand on the reef slope |

T. triserialis |

Shells occurred in sand between coral patches, sand on the reef slope, muddy sand, sand with seagrass and mostly in muddy sand with seagrass |

T. erithreus |

Shells were found in sand between coral patches, sand with seagrass and in the mangrove |

Umbonium vestiarium |

Abundant on fine sandy bottoms. Low tide and shallow subtidal water to a depth of about 5 m |

U. costatum |

On fine sandy bottoms of open coasts. Low tide and shallow sublittoral zone to a depth of about 20 m |

Table 4 Habitat of top shells in Andrew Bay, Rakhine Coastal Region

Species |

Pacific Ocean Regions* |

Indian Ocean Regions* |

Andrew Bay (present study) |

Monodonta labio |

F, Sc |

F |

Sc |

M. canalifera |

F |

F |

Sc |

Tectus fenestratus |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, Ds |

T. pyramis |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, Ds |

Trochus conus |

F, Ns |

F |

F, Sc, Ds, Ns, Ai |

T. maculatus |

F |

F |

F, Sc, Ds |

T. niloticus |

F, Ns, Ai, L |

F, Sc, Ns, Ai, L |

F, Sc, Ds, Ns, Ai |

T. radiatus |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, Ds, L, Tm |

T. triserialis |

F, Sc |

F, Sc |

F, Sc, Ds |

T. erithreus |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, L |

F, Sc, Ds, L, Tm |

Umbonium vestiarium |

F, Ds |

F |

Sc, Ds |

U. costatum |

F, Ds |

F |

Sc, Ds |

Conchological features |

Species |

Type of coiling |

|

Planispiral |

|

Pseudoplanispiral |

Uv, Uc |

Conispiral shell (orthostrophic type) |

Ml, Mc, Tf, Tp, Tc, Tm, Tn, Tr, Tt, Te |

Conispiral shell (hyperstrophic type) |

|

Type of umbilicus |

|

Phaneromphalous |

Tc, Tm, Tn, Tr, Tt, Te |

Hemiomphalous |

Tc, Tn |

Cryptomphalous |

Uv, Uc |

Anomphalous |

Ml, Mc, Tf, Tp, Uv, Uc |

Form of shell |

|

Conical |

Tc |

Discoidal |

Uv, Uc |

Ovoid |

Ml, Mc |

Trochiform |

Tf, Tp, Tm, Tn, Tr, Tt, Te |

Table 6 Conchological features of top shells in Andrew Bay, Rakhine Coastal Region.

Symbols: Ml, Monodonta labio; Mc, M. canalifera; Tf, Tectus fenestratus; Tp, T. pyramis; Tc, Trochus conus; Tm, T. maculates; Tn, T. niloticus; Tr, T. radiates; Tt, Trochus triserialis; Te=T. erithreus, Uv, Umbonium vestiarium, Uc, U. costatum.

There were 12 species of top shells collected from Andrew Bay in Rakhine Coastal Region during the field observation in 2014. The identification is done on the basis of external morphological characters. The Maculated Top Trochus maculatus is highest occurrence and the Latticed Top Tectus fenestratus is lowest populated in intertidal zone of Andrew Bay. During the study, the distribution of top shells widely disperses along the sandy, muddy, rocky, mangrove mud flat, coral rubble, seaweeds and seagrass beds. In this study showed Thanbayar Gyaing and Maung shwe lay Gyaing are the most species distribution and occurrence and the lowest station is Abae Chaung. Andrew Bay is receiving increasing pressure as people continue to utilize the coastal zone for housing, recreation and industrial purposes. This is evident from the disappearance of most of expensive marine commercial species in aquatic ecosystem indicates that the habitat destruction has changed enough to result in the disappearance of these more environmentally sensitive species. Thus it is better in the long term to improve the marine environment so that the existing species can reproduce and grow in abundant and contribute to the local fisheries.

I am indebted to Dr Aung Myat Kyaw Sein, Rector of Mawlamyine University and Dr Mie Mie Sein and Dr San San Aye, Pro-Rectors of Mawlamyine University, for their encouragement and supports in preparing this work. I am very grateful to Dr San Tha Tun, Professor and Head of the Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, for his valuable suggestions and constructive criticisms on this study. I would like to express my sincere thanks to colleagues of Andrew Bay Field Observation Group, Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, for their kindly help me in many ways during field trip. Many thanks go to Daw Lwin Lwin, Retired Lecturer of the Department of Marine Science, Mawlamyine University, for her assistance in preparations of the manuscript. I would like to thank my beloved parents, U Win Maung and Daw Than Than Aye, for their physical, moral and financial supports throughout this study.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Naung. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.