International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 1

1Managing Institute of Hunting, Territorial Hunting Area ATCMS13, Italy

2Freelancer, Sarzana, Italy

3Freelancer, Pontedera Pisa, Italy

Correspondence: Marco Del Frate, Pontedera Pisa, Italy, Tel +393470788268

Received: January 12, 2025 | Published: January 30, 2025

Citation: Bongi P, Fabbri MC, Ulivi S, et al. Spatial use and habitat selection of two differently bred samples of European hares (Lepus europaeus) in the Apennines and its implications in hunting management. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2025;9(1):21-26. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2025.09.00228

Our study focused on habitat use of 21 radio collared European hares in a mountainous area in Tuscany from February to September 2010. The whole sample was constituted by hares of different breeding typologies: 10 hares farmed in cages (farmed hares) and 11 hares bred in a fenced natural area (captured hares). Farmed hares showed smaller home ranges than captured ones during the second bimonthly period, corresponding to the rutting period; while during the first and third bimonthly periods (pre-rutting and post-rutting period, respectively) the hare spatial use was not statistically different for the two typologies. The average home range size of captured hares during the second bimonthly period was 35,5 ± 15,8 ha; whereas farmed hares’ home range was 19,4 ± 6,3 ha. Mean distance between the centers of the bimonthly home ranges was different in relation to the considered typology. The survival rate of the two monitored samples was similar. Farmed hares increased their movement range and reached the maximum spatial use measured for captured ones later than the latter. This aspect could influence the mating success and the consequences related to population density along with useful insights for hunting management.

Keywords: radio tracking, lepus europaeus, habitat selection, spatial behaviour, home range, hare management

The European hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas, 1778) is a game species that has been introduced to many parts of the world1. In the last few decades, the European hare population has suffered a progressive decline,1–3 mainly in reason of habitat modifications, such as changing type of agricultural,4–8 climate changes, hunting pressure, predation and diseases.9 Hares require different habitat structures at different times of the year, and diversity at the localized, within-habitat scale is particularly important in a predominantly pastoral landscape.10

As a matter of fact, trophic requirements affect the spatial behavior and habitat selection of wild animals. Still, little is known about spatial behaviour and habitat use of European hare in mountainous habitat. In the 1980s several studies have used radio tracking techniques4,11–12 to study hares in agricultural landscapes in different parts of Europe, obtaining differing results. Kunst13 reported an average home range size of 28.7 ha in a salt marsh habitat. In contrast, larger home range sizes have been observed in various other landscapes, including intensively farmed agricultural areas,14 lowland pastoral regions,15 harvested arable fields,16 and open habitats in the southern hemisphere.17,18 The spatial behaviour of mountain hare (Lepus timidus) investigated in a mountainous habitat showed a home range size varying between 11.9 ha and 77.2 ha.19 Several studies have focused on European hare spatial use and responses to seasonal changes in habitats characterized by farms,14,16 arable crops, grassland and woodland.7,9 Still, very little is known about habitat selection in mountainous and non-agricultural landscapes, where crops are scarce or absent.7,20,21

In Italy, the managing institute (A.T.C.) releases a high number of hares for hunting purpose every year. Generally, released hares are either born and bred in large fenced areas or born and bred in cages. Information about spatial behaviour and introduction success of these two typologies of hares is very scarce. Some studies show that hare mortality rate after 3 months from release was between 60% and 80%22,23 thus, the managing institute often goes to great expenses without certain results.

Considering the request whether of A.T.C. or of hunters we conducted a study from February to September, when hare hunting is forbidden. Our main purpose was to assess hare home range size and habitat selection in a mountainous area, also taking into consideration the possible behavioural differences due to different breeding conditions: hares bred in open areas or hares bred in cages. Assessing the survival rate of these two typologies. Could be useful with respect to hunting management.

Study area

The study was carried out in Prati di Logarghena (44° 23’ N, 9° 56’ E), a mountainous area located in the province of Massa-Carrara, Tuscany – Italy. The altitude varies from 500 to 1100 m a.s.l. The climate is temperate and characterized by a high humidity rate, with hot and dry summers, and cold and rainy winters. The snow falls from November to February/March with moderate intensity. The area is characterized by three different habitats: on the top of the Apennine pasture characterized by herbaceous species (Juncus trifidus, Anemone narcissiflora, Aquilegia alpine); the mid-altitude area is covered with woodland characterized by beeches (Fagus sylvatica), birch-trees (Betula alba) and hornbeams (Carpinus betulus); in the lowest part there are meadows characterized by herbaceous species such as Nardus stricta, Festuca spp. Manyanthes trifoliata, Bromus erectus, Sassifraga oppostifolia, and Euphorbia spp. The most widespread and typical species of this area is the jonquil (Narcissus jonquilla). Hare natural predators are represented by marten species (Martes martes and Martes foina), fox (Vulpes vulpes) and wolf (Canis lupus), whereas birds of prey were chiefly represented by the common buzzard (Buteo buteo) and goshawk (Accipiter gentilis).

Data collection

Radio-tracking techniques were used to collect data from 21 adult hares monitored by discontinuous radio tracking from 1 February 2010 to 31 August 2010. The released sample was constituted by hares bred in captivity and foraged artificially, (“Farmed hares”; n = 9) and hares bred in a wild fenced area (“Captured hares”; n = 12). The latter were captured with vertical drop nets and released in the study area the following day, while “Farmed hares” were taken from the cages and released the same day.

Locations were calculated by triangulation, with bearings obtained from three different landmarks24 using the “loudest signal” technique,25 and then plotted onto a 1:10,000 digitized map of the study area.26 On January the 30th, adult hares were fitted with Bio track collars (Bio track, UK) equipped with mortality sensors and released in the area. Sika Bio track receivers and three-element hand-held Yagi antennas were used to locate animals. At least 12 locations per animal were taken every month, uniformly distributed over the day. The accuracy of the fixes was determined on the field using test transmitters placed in different habitats,27 during each monitoring session. The average of error per localization was 47.3 meters, therefore an error polygon of 50 square meters was used.

Statistical analysis

Using Ranges VI software, the Kernel method was used to assess home range size in each bimonthly period, using 95% (K95%) of available locations. We estimated home ranges with fixed kernel estimator,28 as it has so far proven to be one of the most reliable estimators of animals actual range use.28,29 K95% represents the core area within which the hare is most likely to perform its activities.30 The following bimonthly periods were set apart: pre-rutting period (February-March), rutting period (April–May), post-rutting period (June–July). Home range sizes were log-transformed and successfully checked for normality with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We checked for variations between the home-range sizes of “Farmed” and “Captured” hares using the t-test for independent samples. The overlap of consecutive bimonthly period home range was assessed calculating the distance from the previous home range center and testing the different data with ANOVA.

The habitat selection was assessed using compositional analysis, in order to solve the unit-sum constraint typical of compositional data.31,32 Used and available habitats were compared on two levels. We first analyzed the home range selection within the study area by comparing the proportion of habitats in the K95% home range with the proportion of habitats in the study area (therefore on a broad scale). The study site was defined as the area including all the locations collected during this research and calculated using the Minimum Convex Polygon Method 100%.33 Secondly, we examined the habitat use within the home range on a fine scale, by comparing the number of fixes in each of the different habitat types with the proportion of the habitat in the K95% contour line. All data necessary for compositional analysis were obtained with the use of Arc View GIS 3.2. Assuming that habitat use differed from random use, we ranked the habitats according to their respective use on both levels and tested for significant differences among them. Compositional analysis and statistics were computed with an Excel macro,34 which also carried out the randomization procedure recommended by Aebischer32, a procedure made necessary by the potential non-normality of our data.32 For each compositional analysis of “Farmed” and “Captured” hares, habitat use, Wilks’s λ and randomized P values were reported as P values of each significant difference between ranks (univariate t-test).

We used four habitat types for compositional analysis: deciduous coppice forests (DCF: 336.44 ha, 49.4%), meadows and shrubs (MS: 259.34 ha, 38.1%), chestnut wood (CW: 55.29 ha, 8.1%) and pasture with tree (PA: 29.92 ha, 4.4%). We reduced the number of habitat types to three at the second level of compositional analysis, by pooling those habitats that were characterized by a similar vegetal structure, i.e. chestnut wood without undergrowth and pasture with some other species of trees (CWP=CW+PA). According to this classification, all habitats in our database were documented as being utilized by the monitored hares. This approach ensured accurate resource selection classification, thereby avoiding misclassification, as strongly recommended by Bingham.35 We finally tested for variations in habitat use by “Farmed” vs. “Captured” hares by adding the different breeding typology (parameter) as an independent variable in Wilk’s log-ratio matrices and by analyzing these matrices with a MANOVA test.32 All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 13.0 program.

Survival rate

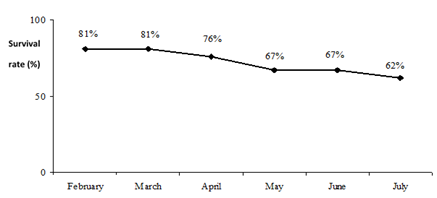

Survival rate was assessed on a monthly scale, recording deaths in relation to the monitoring period and to the typology of breeding. Since deaths were few, a statistical approach would not have been relevant, and so the survival rate was only reported in a graphic way (Figure 1). However, our results show that there is no significant difference within the survival rates of the two typologies. On table 1 we reported the specific of dead individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hares survival rate during the study period, expressed in proportion to the original sample.

|

Month |

Total number of deaths |

Number of dead Farmed hares |

Number of dead captured hares |

|

February |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

March |

- |

- |

- |

|

April |

- |

- |

- |

|

May |

1 |

- |

1 |

|

June |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

July |

1 |

- |

1 |

Table 1 Number of hares found dead in different months, in relation to the different breeding typology

Space use

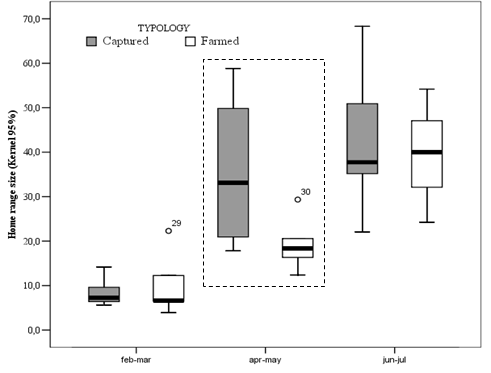

Bimonthly home range size (Figure 2) of Farmed (n = 7) and Captured (n = 9) hares did not statistically differ in the pre-rutting period (Farmed hares: mean ± SD: 10.3 ± 7.4 ha; Captured hares: 8.4 ± 2.9 ha; t-test for independent samples: d.f. = 15, t = -0.234, P = 0.824). Similarly, the home range size in the post-rutting period of Farmed (n = 6) and Captured (n = 6) hares did not statistically differ either (Farmed hares: mean ± SD: 39.5 ± 15.0 ha; Captured hares: 42.9 ± 16.2 ha; t-test for independent samples: d.f. = 11, t = 0.282, P = 0.785). In contrast, home range size of Farmed (n = 7) and Captured (n = 8) hares during the rutting period were statistically different with Farmed hares showing a smaller home range than Captured ones (Farmed hares: mean ± SD: 19.4 ± 6.3 ha; Captured hares: 35.5 ± 15.8 ha; t-test for independent samples: d.f. = 14, t = 2.576, P = 0.024).

Figure 2 Seasonal home-range sizes recorded for the two typologies of hares in the Prati di Logarghena, in the Appennines (central Italy), assessed using Kernel 95% methods. Broken boxes show significant differences (P<0.05) between the two categories (t-test for independent samples; see text for details).

The center of the home range from the second to the first bimonthly period shifted with an average of 357.12 ± 83.37 meters for Farmed hares and with an average of 210.93 ± 186.72 meters for Captured hares. The center of the home range from the third to the second bimonthly period of Farmed hares varied an average of 177.66 ± 100.78 meters and that of Captured hares varied an average of 374.88 ± 136.17 meters. The differences between center distance of Farmed and Captured hares during the study period were statistically significant (ANOVA farmed vs captured: F = 6.9; P = 0.017) (Table 2, Figure 2).

|

Typology |

Bimonthly |

Mean of HR centre distance (meters) |

SD |

|

Captured |

1 |

210,93 |

186,72 |

|

Farmed |

2 |

357,12 |

83,37 |

|

Captured |

1 |

374,88 |

136,17 |

|

Farmed |

2 |

177,66 |

100,78 |

Table 2 Mean and standard Deviation of Home Range center distance in relation to typology and bimonthly period

Composition analysis

The compositional analysis of the home ranges within the study area (first level) revealed a non-significant departure from random use during each bimonthly period for both typology of hares (Table 3). Variations occurred in the rank of meadows and coppice wood. Farmed hares always selected meadows and shrubs first, while Captured hares preferred coppice wood during the two first bimonthly periods. As reported in table 3, both typologies avoided pasture with trees and chestnut wood. Therefore, at the first level of compositional analysis there was no difference in habitat use between the two samples of hares as confirmed by MANOVA test (first level: λ = 0.795, F = 2.497, P = 0.079). At the second level of compositional analysis, as the proportion of fixes for each habitat was compared with the proportion of the habitat in the Kernel 95% contour line, both Farmed and Captured hares showed again a non-significant departure from random use in the study period (Table 3).

|

Farmed hares |

Captured hares |

||||||

|

Level of analysis |

Bimontlhy |

Wilk’s λ |

Pr |

Ranked habitat types |

Wilk’s λ |

Pr |

Ranked habitat types |

|

first |

pre-rutting |

0,0233 |

0,121 |

MS>DCF>PA>CW |

0,6248 |

0,321 |

DCF>MS>CW>PA |

|

rutting |

0,0004 |

0,064 |

MS>DCF>PA>CW |

0,3820 |

0,146 |

DCF>MS>CW>PA |

|

|

post-rutting |

0,0001 |

0,255 |

MS>DCF>PA>CW |

0,8052 |

1,000 |

MS>DCF>CW>PA |

|

|

second |

pre-rutting |

0,5819 |

0,510 |

DCF>MS>CWP |

0,8160 |

0,498 |

DCF>MS>CWP |

|

rutting |

0,2247 |

0,258 |

MS>DCF>CWP |

0,6582 |

0,344 |

DCF>MS>CWP |

|

|

post-rutting |

0,0022 |

0,271 |

MS>DCF>CWP |

0,8326 |

0,874 |

MS>DCF>CWP |

|

Table 3 Habitat selection by Farmed and Captured hares determined by compositional analysis in the Apennines study site, in central Italy

The analysis also ranked the habitats used by Farmed and Captured hares in the same order of preference, with the exception of the second bimonthly period, when Farmed hares selected meadows and shrubs as first choice while Captured hares preferred deciduous coppice wood. After the rutting season (third bimonthly period), Captured hares also used meadows and shrubs as first vegetation type. The same habitat preference of Farmed and Captured hares was confirmed by MANOVA test, performed at this second level of analysis (second level: λ = 0.917, F = 1.366, P = 0.270).

Therefore, the rank of selected habitat types was the same for the two differently bred typologies during the study period, as all hares preferred meadows, shrub land and coppice forest on pasture with tree and chestnut wood. As a matter of fact, there were no differences in selection between different bimonthly periods, as confirmed by results of the univariate t-test at the first and second level of analysis, for Farmed and Captured hares (Table 4).

|

Farmed hares |

Captured hares |

|||||||

|

First level |

Deciduous coppice wood |

Pasture with tree |

Chestnut wood |

Deciduous coppice wood |

Pasture with tree |

Chestnut wood |

||

|

Pre-rutting |

||||||||

|

Meadows |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

||

|

and shrub |

||||||||

|

Deciduous coppice wood |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||

|

Pasture |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

||||

|

with tree |

||||||||

|

Rutting |

||||||||

|

Meadows |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

||

|

and shrub |

||||||||

|

Deciduous coppice wood |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||

|

Pasture |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

||||

|

with tree |

||||||||

|

Post-rutting |

||||||||

|

Meadows |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||

|

and shrub |

||||||||

|

Deciduous coppice wood |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||

|

Pasture |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

||||

|

with tree |

||||||||

|

Second level |

Deciduous coppice wood |

Pasture and chestnut |

Deciduous coppice wood |

Pasture and chestnut |

||||

|

Pre-rutting |

||||||||

|

Meadows |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

||||

|

and shrub |

||||||||

|

Deciduous coppice wood |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

Rutting |

||||||||

|

Meadows |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

||||

|

and shrub |

||||||||

|

Deciduous coppice wood |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

Post-rutting |

||||||||

|

Meadows |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||

|

and shrub |

||||||||

|

Deciduous coppice wood |

+ |

+ |

||||||

Table 4 Results of univariate t-tests of compositional analysis of habitat on first level (upper panel) and second level (lower panel) for Farmed (left panel) and Captured (right panel) hares in the “Prati di Logarghena”

Randomized P values (1000 interactions).a

On each line habitat classes to the left of the symbol > are selected over those to the right (>>> when the difference between two consecutive habitat classes is P<0.05). Significant departures from random use are indicated by λ and randomized bold P values (1000 interactions). On the second level of analysis, Pasture with chestnut (CWP) were obtained by pooling the habitats Pasture with tree (PA) with chestnut wood (CW). DCF, deciduous coppice forests; MS, meadows and shrubs (Table 4).

Our results show that there were differences in the home range size of the two typologies of released hares. The size of territorial range occupied by released hares ranked among the highest ranges ever reported for free-living hare populations.13,14,16 Different factors are known to account for the size of the hare home range, such as population density,36 seasonal availability of resources,10, 37 farming and agricultural practices,4,7,8 and body conditions.38 This study showed that the different breeding typology also influences hare’s spatial behaviour.

As a matter of fact, both Farmed and Captured hares had the same home range size in the first bimonthly period after release, when it is important to adapt to the new area. Then, during the rutting period, Captured hares had a larger home range than farmed ones. Within two months the Captured hares learned to move on the new territory and to cover a larger area, thus enhancing the chances to meet a potential partner and ensuring the breeding success.

In the third bimonthly period, Farmed hares expanded their home range and occupied an area as wide as that occupied by Captured hares. It was interesting to observe the trend of home range shift. As a matter of fact, the distance between the home range centres of third and second bimonthly period was higher for Captured hares than for Farmed hares. Rühe and Hohmann36 pointed out that habitat structure and availability of resources do not influence the variations in hares’ home ranges, while the breeding typology seems to influence the home range patterns.38

Accordingly, our study showed that habitat selection did not vary in reason of resources distribution. Hewson39 and Späth40 showed that hares preferred to feed on cereal fields and other studies revealed a preference for cultivated crops rather than weeds and wild grasses.7,20 Where crops fields were absent, hares shifted their diet on grasses species.41-43 Dingerkus and Montgomery44 found that grasses were a very important food source for Irish hare (Lepus timidus hibernicus) and similar results were shown by Paupério and Alves45 for Iberian hare (Lepus granatensis).

In our study hares did not show a preference for any particular habitat type and selected resources according to their availability. This could be related to the poor habitat type and even though habitat selection was not statistically significant, the first chosen habitat was always meadows and open areas, characterized by herbaceous species that are more energetic than undergrowth species present in the woodland. European hare includes many plants species in its diet, but the most important ones were genus Bromus, Festuca, Euphorbia46 as hares must satisfy energetic request of 122 kcal per kilogram during spring-summer, and 160 Kcal per kilogram during autumn-winter.47 So, the food intake is the same for Farmed and Captured hares, and this could account for the similar habitat selection.

In contrast with other studies conducted in Italy, survival rate was acceptable and 62% of released hares were still alive after 6 months. The unusually low mortality rate may be attributed to the low density of natural predators and the mild weather conditions during the winter and spring of 2010. These favorable conditions allowed us to extend the study until the onset of the hunting season. Further research is needed to investigate spatial use and habitat selection during the winter months when hunting is permitted.

This study has some useful information for understanding spatial behavior, home range, and habitat selection by released European hares in mountainous conditions when breeding was in captivity versus free living. Our results indicated a significant influence of the breeding typology on the home range size and movement pattern. Captured hares had a greater home range size during the rutting period, probably to increase mating opportunities, whereas farmed hares extended their home ranges later in the study. These behavioral differences emphasize the importance of considering breeding origin in hare management and release strategies. Although habitat selection did not show any statistical significance, hares always preferred grassland and open regions with herbaceous species than regions with undergrowth species presumably for higher energetic values. Thus, it may be possible that habitat features are enough to fulfill the nutritional requirements of the species in these mountainous regions. The survival rate of 62% six months after release was higher than reported in similar studies. This may be attributed to the low density of predators and mild weather conditions during the study period, emphasizing the importance of environmental factors in release success.

Future research should concentrate on spatial behavior and survival during the hunting season to further refine management strategies. The resource selection and habitat use study in areas of different environmental pressures will also give a more complete understanding of hare adaptability and long-term conservation success.

As regards the success of released hares, breeding typology has been found to play no key role in hare adaptation; therefore the hunting management might invest in the least expensive typology. On the other hand, when we take into consideration the different spatial behaviour and its consequences, Captured hares seemed nevertheless to benefit from their ability to quickly control a wider home range in a smaller amount of time then Farmed hares, thus enhancing their chances of survival and their reproductive success. Hence, from an economic point of view Captured hares should be preferred, since a higher number of offspring would increase the availability of preys.

B.P, U.S, and D.F.M. data collection, data analysis, wrote the main manuscript text; F.M.C. wrote the main manuscript text; B.P., D.F.M., and F.M.C. prepared all figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

None of the animals considered in this study were ever handled or otherwise altered.

Not available.

This study was funded by Province of Massa-Carrara and Ambito Territoriale di Caccia ATC MS13. We wish say thanks to each hunters of ATC MS13 that support us in filed operation and capturing hares.

The authors haven no competing interests.

©2025 Bongi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.