International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9862

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 1

1Department of Zoology, Asutosh College, India

2South Duillya High School Sankrail, India

3Arambagh Vivekananda Academy, India

4Chaltakhali R.G.B.C. Institution, India

Correspondence: Deep Chandan Chakraborty, Department of Zoology, Asutosh College, India., Tel +919836969215

Received: January 13, 2025 | Published: January 31, 2025

Citation: Chakraborty DC, Mal M, Dhara A, et al. Behavioural ecology of Asian paradise flycatcher (Terpsiphone paradisi) with special reference to nesting and foraging within a bamboo-dominated forest patch of Damodar River floodplain, Howrah, West Bengal. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2025;9(1):28-32. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2025.09.00229

The study centered upon a summer visiting population of Asian Paradise Flycatcher (Terpsiphone paradisi; Linnaeus, 1758; IUCN: Least Concern), a medium-sized passerine bird nesting within a bamboo-dominated habitat in a flood plain of Damodar river at Bangalpur, Howrah, West Bengal. Ad libitum sampling, focal group sampling and time budget analysis has been conducted for three consecutive breeding seasons (March to August of 2022-24) to develop an understanding of their behavioural ecology related to foraging and nesting. Rich entomofaunal diversity in and around agricultural landscapes provides ample foraging resources for establishing their breeding territories. Adults prefer actively flying insects, predominantly dragonflies breeding in freshwater sources nearby, and opt for foraging strategies like sally, sally gleans, perch to ground sallying. Findings show both parents engage in nest construction, foraging and incubation duties. Breeding groups were found to employ non-aggressive anti-predator strategies like dummy nest construction, and proximity nesting with drongo nests. They optimize the nest elevation, foraging radius and duration of foraging outings at different stages of breeding.

Keywords: Asian paradise flycatcher, passerine, Howrah, behavioural ecology, foraging ecology, nesting ecology

The Asian paradise flycatcher (T. paradisi; Linnaeus, 1758; IUCN: least concern), is a medium-sized passerine that inhabits forests and well-wooded habitats in different parts of Asia. It is a widespread resident in the Indian subcontinent and migrates seasonally. In the state of West Bengal, it is a summer visitor comes to breed in the riverine plains where an abundance of non-cultivated vegetation still exists.1,2 Being socially monogamous, both males and females take part in the nest-building, incubation, brooding, and feeding of the young.3 Males occur in four morphs in the same population (WL-white in colour with a long tail, RL-rufous in colour with a long tail, MM-Moulting morph in rufous-white colour with a long tail and RS-rufous in colour with a short tail). Females are always rufous coloured (much like RS males) and lack elongated tail feathers unlike their counterparts.3 They primarily are insectivores and rely on the entomofaunal abundance of an area. These birds prefer to choose undisturbed, shady riverine alluvial plains with an abundance of vegetation predominated by bamboo (Bambusa bambos) thickets and its associated entomofaunal diversity.1,4 Young bamboo shoots and saps offer rich resources for different larval stages of insects, which in turn serve as forage for a community of insectivore birds, including T. paradisi. In this study, we document the foraging and nesting ecology in detail, particularly the way they manage both while nest enemies are around. Here, we studied the foraging behaviour with respect to foraging materials, foraging strata, foraging strategies, rate of foraging, and roles played by males and females in foraging. Moreover the study focuses to document minute details related to behavioural ecology, factors associated with the nesting success, which in turn will serve as useful information for species monitoring and designing site-specific conservation measures.

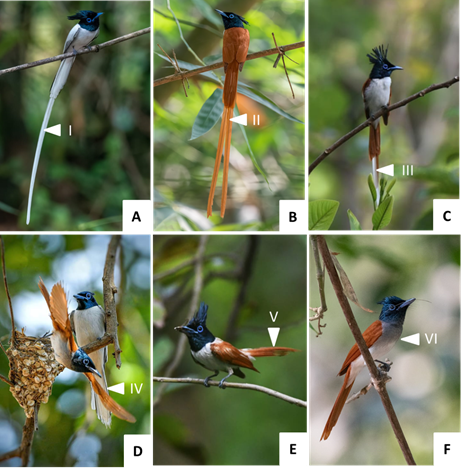

Breeding pairs and male morphs

The study site was occupied by 5 male morphs (WL: white, long-tailed, RL: long-tailed rufous, MM: moulting, morph-long tailed, WS: moulting white, short-tailed, RS: rufous, short-tailed) and the rufous female (RF). The rufous female has a shorter square-ended tail without the long central feathers, greyish chin and throat, shorter crest, and comparatively dull bluish eye ring (Figure 1: A-F). All five morphs of males comprised of paired bright blue eye ring, long well-developed black crest on the head and bright black neck, differing in body colour - white and rufous body plumage.3, 2 Moulting male morphs, both short and long-tailed, were seen to participate in nest construction and differ in plumage from one another (Figure 1).

Figure 1 a) Male-WL: paired white long central tail feather; b) Male-RL: paired rufous long central tail feather;

c) Male-MM: paired rufous-white long central tail feather; d) Male-WS: square-ended white short tail feather;

e) Male-RS: rufous short tail feather; f) Female-RS: shorter crest, grey chin and throat, rufous short square-ended tail without a long central feather.

Study site

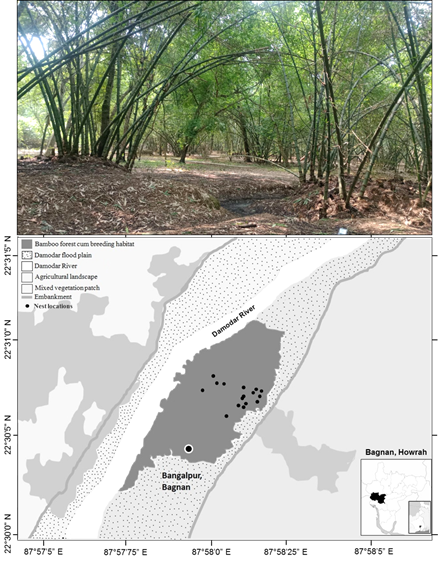

The study site is located at Bangalpur village, Bagnan block-I, Howrah (22°30'52.8"N, 87°58'06.2"E) at the flood plain of Damodar river covering roughly 914.3 acre predominated by seasonally harvested bamboo vegetation, mixed with mango (Mangifera indica), sirish (Albizia lebbeck), shaal (Shorea robusta) and variety of herbs, shrubs and grasses (Figure 2). This area supports a diverse bird community for its rich entomofauna and relatively undisturbed characteristics. Insectivores such as Black-hooded Orioles, Black-napped Monarch, Rufous Woodpecker, White-throated Fantail also seen to construct nests in tandem with T. paradisi. Rich supply of nesting materials and foraging resources makes the site abode for bird community. For many years the landscape attracts the T. paradisi for nesting purposes in summer. The area gets seasonally flooded in late monsoon (Aug-Oct) by the rain-fed Damodar River, making it a suitable maturing ground for bamboo. While the T. paradisi nesting completed by July well before the area becomes water-logged (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Location of the potential habitat - bamboo forest patch at the floodplain of Damodar River in Bangalpur, Bagnan area (22°30'52.8"N, 87°58'06.2"E) within Howrah district. Nest locations (small black dots), landuse and vegetational features have been mentioned.

Data collection

Data were collected during three breeding seasons (2022–24). The study has been conducted during summer months (March 2022-24) up to the late monsoon (August, 2022-24). The majority of the nests were identified and observed during construction, egg-laying, incubation and nursing of nestlings. Each nest were marked with a number with year tags for data keeping and analysis (N=16). For all nests, the nest site parameters were recorded along with the behavioural repertoire. Time budget analysis and focal group sampling were performed to estimate relative Habitat features and foraging resource diversity were recorded.

Ad libitum sampling followed by focal group sampling of a nesting group of T. paradisi: Volunteers had recorded various behavioural repertoire of free-ranging T. paradisi at the nesting site for separate three-time slots (morning: 7:00 - 10:00 hrs; mid-day: 10:00 - 13:00 hrs & afternoon: 1:00 - 5:00 hrs.). During this period detailed behavioural activities and patterns were identified (based on field survey and literature reviewed) and assigned names for future discrimination. Later on, the time budget of each behaviour was performed. 2 hours each from three-time slots were invested for focal group sampling.

Study on foraging ecology and foraging resource diversity

Foraging activities were recorded in three-time slots (stated earlier) from their arrival to the spot (mid-March) up to the completion of nesting (mid-August) for three consecutive seasons (2022-24). Direct observational records (photographs/videos/notes) on relative preferences of forage resources, foraging strata, strategies, and sex-wise responsibilities were studied on the nesting groups of T. paradisi. Nest-wise foraging data were recorded each year to identify the overall foraging strategy depending on the position, and stages of nesting. Along with the foraging ecology of the bird, a seasonal sampling of local entomofauna has been performed to assess the diversity within the foraging range from the nesting site. Quadrate sampling (ground-dwellers), sweep netting (active flyers), aquatic netting (aquatic larvae of amphibiotic insects) bush beating (passive flyers) pan-trapping (floral visitors) etc. used for collecting entomofauna. As per the nest concealment hypothesis, open cup-shaped nests are at high risk of nest predation, thus concealment within ambient foliage is key to nest success. During our routine survey, we measured (Nikon Forestry Pro II Laser Rangefinder) the nest-wise minimum distance (d min) from which nests were not visible (discriminated from the foliage) at each phase of the breeding season.

Behavioural repertoire of foraging and nesting

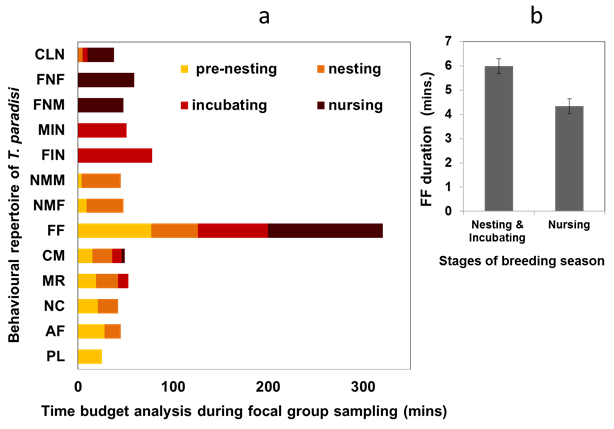

Seasonal observations of the breeding group of T paradisi give a detailed repertoire of behaviours. Major phases of their breeding are identified as pre-nesting, nesting, incubating and nursing. Time budget analysis indicates the phase-wise prevalence and decay of certain behaviours while some stay relevant throughout. Foraging flight (FF) for searching for insects from the surroundings has been persistent and performed by both sexes (Figure 3a). However, time (mins) invested in FF declines during the nesting and incubation period since both sexes equally share the responsibilities of nest construction, attendance and egg incubation. Both sexes are reported to alternate their foraging flights for nest guarding, although the breeding period. Parental investments like feeding the nestling and nesting material collection were shared among partners almost equally though it is slightly inclined towards females. Grubs were fed to the nestlings rapidly cast out as faecal sacs, removed and thrown 5-10 metres away from the nest location (Figure 5e). From a hygiene point of view, cleaning of feces (CLN) behaviour is significant since both sexes perform it dutifully in the nursing stages. However other cleansing jobs were done by the pair during the nesting and incubating stages to keep nests free of ectoparasites and fungus5. Studies show growth of the fungi is detrimental to nests since it can decompose the nesting materials6 and infect newly hatched as well.7 These passerines are strongly territorial and engage in male-male rivalry to establish breeding supremacy. The male nest owners attack and chase down the opportunistic intruders (ACM) all through the breeding period. Territorial displays from prominent perch or coordinated flight displays are less frequent in T. paradisi unlike the other bird species.8 The duties of nest construction and incubation were often equally shared;1 however, some inter-nest variations were reported (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Time budget analysis (mins. spent) from Ad libitum sampling and followed by focal group sampling done at a specific nest site. Behavioural repertoire recorded in T. paradisi in phases of breeding seasons. b) Foraging flight duration varies in various stages of breeding.

Abbreviations: CLN, cleaning of nests; FNF, feeding nestlings (Female); FNM, feeding nestlings (Male); FIN, female incubating on nest; MIN, male incubating on nest; NMM, bringing nesting materials (Male); NMF, bringing nesting materials (Female); FF, foraging flight; CM, chasing other males; MR, male rivalry; NC, nest construction; AF, attracting females; PL, play

Behavioural ecology of foraging

Based on the behavioural survey and insect sampling data, it can be stated that T. paradisi chooses to feed on actively flying insects compared to sedentary forms. Dragonflies (order – Odonata) are the initial preference followed by honey bees, wasps & other flies (order – Hymenoptera), spiders (order -Araneae), moths & butterflies (order – Lepidoptera), crickets and grasshoppers (order – Orthoptera). Rarely did they feed upon insects belonging to the order – Coleoptera, Isoptera, and Hemiptera (Figure 4). Being agile birds they access the air, stem and base of bamboo, mango tree etc. available for collecting the foraging materials. They make use of sally, glean, and perch to ground sallying as the foraging strategies. Rarely, they pick up foraging materials from the ground. If required they try to restrict themselves upto the height 4-5 ft from the ground. It seems that foraging specialization in T. paradisi has a close relation with their habitat selection, similar scenarios of strong habitat-diet relation were reported by other authors (Höhnet al. 2024).

Observational evidence shows FF duration remains around 6 mins (5.98 ± 0.3 S.E.) in nesting and incubating stages, while it drops to 4.3 mins (4.33 ± 0.46 S.E.) with an increase in FF frequency during the nursing stage (Figure 3b). It seems they have optimized their foraging outings in such a way so that they can search a prey within 4-6 mins on average. Considering nest predation as one of the major causes of reproductive failure, optimization of FF duration plays an important role in many passerine birds since it benefits through better nest guarding and eventual offspring survival.9–11 Studies show many bird species, go through a crucial trade-off between optimum foraging and nest protection during the nesting period.12

The foraging frequency and radius depend on the condition of the nest and the distance between the nesting site and the foraging site. Generally, they prefer to collect foraging materials (foraging radius) ranges within 10-50 m with few exceptions (Figure 6a). But the frequency of foraging is higher in the brooding period which is about 15–20 times per hour. The strategy has been associated with nest success since unattended nests attract predators, they shorten the empty nest period first by alternating foraging outings between the sexes, and second by fixing an optimum radius for foraging. While feeding they feed one sibling at a time as per their age generally. But, sometimes as per the type of food, they choose the sibling. Though the foraging responsibility is executed by males and females, in most cases females are active in feeding chicks. While males are active in territory protection while foraging and incubation (Figure 4).

Nest site parameters and nest success

Similar to other studies conducted on other closely related species13,14 some nest site parameters were recognized on which nest success depends variedly. Height above ground (ft), dbh (inch), concealment (distance from which nest is unidentifiable), foraging flight time (mins), temperature and employing anti-predatory strategies like constructing a nest close to other aggressive species or occurrence of dummy nests were studied. Moreover, in several studies, nest elevation in particular is seen to depend on multiple habitat factors such as tree types, branch point availability, and number of competing nesting pairs in close range, distance from foraging resources, freshwater bodies, wind direction and occasional dummy nesting habit.15,16 In our case, the vegetation type chosen for building nests is exclusively bamboo (Bamboo bambusa) and rarely Mangifera sp. and Shorea sp (Figure 5f-h). Nest concealment is considered crucial for offspring survival and better clutch size. In this connection, we found the average minimum distance (d min) of nest concealment is 15.4 ft (15.43 ± 1.35 S.E.) (Figure 6cs). Foliage colour in summer remains pale brown, dominated by dry bamboo leaves that provide good camouflage for the nests while after a few showers, fresh leaves create contrast in the habitat making it easier to spot nests even from closer distances even if there is no active bird movement. Nesting materials chosen are primarily the midribs of dry bamboo leaves that do not decompose even after heavy rain, along with spider web threads, dry seed pods of Dioscorea sp. were used to decorate from outside (Figure 5b-c). We have performed a nest-wise focal sampling of T. paradisi pairs (N=16), showing different nest elevations and foraging radii were explored during their nesting attempt (2022-24) out of which few (03) nests failed to produce fledglings Figure 6b (Figure-5).

Figure 5 Nests attribute - substrate, placements and vegetation type. a) Close-up of the cup-shaped nest architectures; b) concealment; view of bamboo leaf midribs used in nest construction; c) locally common Dioscorea sp. seeds used to decorate the exterior of the nests. d) concealment of nests; e) Fecal sac cleaning behaviour; f–h) nesting trees – bamboo (predominant) mango& shaal tree.

Besides this, some pairs were reported to construct 2 to 3 nests during nesting season, considered a common nesting strategy decoy for predator diversion.17,18 Selection of nest sites close to the drongo nest is an anti-predator strategy often opted by many species.19,20 Such proximity nesting has been reported in the case of some T. paradisi nests and benefitted from their aggressive defense strategy against the raptor raids. We have calculated the nesting success percentage of proximity nesting compared to non-proximity among the nests (N=16) studied overall (percentage of success: prox. = 77.77 % & away = 57.14 %). The morphological features such as nest (outer diameter, depth of nest cavity etc.) are mostly phylogenetically conserved within species and are least likely contributors to nesting success.21,22 In our study habitat and various other locations (not reported in this study), the close availability of artificial and natural freshwater bodies is integral to nesting success since these aquatic bodies serve as the breeding pool for many of the odonate species. These odonate flies serve as vital diet components of nestlings and fledglings of T. paradise (Figure 6).

T. paradisi is the summer visiting breeding populations that use naturally forested landscapes in southern West Bengal. In this study, one unique breeding patch has been reported that supports a highly diverse and abundant entomofaunal community with suitable vegetation for nesting and a supply of freshwater bodies for the maturation of insect larval stages. Various behavioural strategies associated with nesting and foraging and their possible ecological significance were discussed in detail. T. paradisi was seen to optimize foraging flight radius, foraging flight duration, nest elevation, construct dummy nests, and also adopt other anti-predator strategies to ensure offspring survival. The study generates useful information on the behavioural ecology of the nesting, breeding and foraging strategies and preferences of T. paradisi. We look forward to the successful application of these insights in habitat restoration conservation initiatives to favor the breeding populations of paradise flycatchers in floodplains of southern Bengal.

DC have conceptualized, designed the experiments and DC and AD have written the manuscript. TM MM and DC have collected field data and documented photographically. DC, AD and MM have analyzed the observations.

We extend our gratitude to Soumyadip Mondal, Snehasish Choudhury, Baharuddin Sk, Suvendu Kha, Subhadeep Saha, Jayanta Halder and Debarnab Sen for their field and photographic inputs specific for the study area. We would like to thank the heads of the affiliated Institutes for providing the necessary infrastructure for this research, and the locals of Bangalpur village for cooperation during the study tenure.

Authors declares that they do not have any kind competing interests in the work described in this manuscript.

©2025 Chakraborty, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.