eISSN: 2576-4497

Case Report Volume 1 Issue 1

1Clinical of Maxillo-Facial Surgery, Belgium

2Clinical oncology Medical, Belgium

3Department of Laser Therapy Unit, Belgium

4Service of Medicine, Belgium

Correspondence: Jean Klastersky, Service of Medicine, Jules Bordet Institute, Universite Libre de Bruxelles ULB Tumor Center, Rue Heger-Bordet 1, 1000 Brussels, Belgium

Received: February 13, 2017 | Published: March 20, 2017

Citation: Massaut E, Klastersky J, Genot MT, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case report and a critical review of surgical management. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2017;1(1):1–5. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2017.01.00001

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a relatively rare but serious complication of bisphosphonates (and denosumab) therapy for which conservative or surgical treatment is advocated. We report an exemplative case and review recently published studies of surgical management of ONJ. The total population surveyed in those 7 studies included 1459 patients. Operative treatment was applied in 53-100% of the patients and non-operative treatment in 0-47%. Response after surgery was seen in 59-87% (actually 938 patients out of 1204-77% - responded). Non-operative treatment was successful in 20-100% (40 out of 250–16%-patients responded). The highest range of response was seen in stage 2 diseases (22-67%). Our review supports the use of a relatively early surgical approach in the management of ONJ.

Keywords: osteonecrosis, reconstructive surgery, jaw surgery, immunology

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) has been initially reported in the early 2000s in patients with cancer having received bisphosphonates for the management of skeletal metastases; later ONJ was also described in cancer patients treated with denosumab, for the same indication. The extensive discussion of the pathogenesis of ONJ is beyond the scope of this review; suffice it to say that bisphosphonates and denosumab strongly inhibit the function of osteoclasts, resulting at the end in a status of “frozen bone” which causes a reduced capability of resistance to infection and reparation after injury.1,2 In a recent meta-analysis, it was found that ONJ occurred in 89(1.6%) of 5,723 enrolled cancer patients; 37(1.3%) received zoledronic acid and 52(1.8%) received denosumab. Tooth extraction was reported in 62% of these patients with ONJ. Therapy was conservative in >95% of the patients; ONJ resolved in 36% of the patients.3 Other reviews found higher incidence of ONJ (4%) in bisphosphonates-treated cancer patients.4 Recent guidelines issued by the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) define ONJ as an area of exposed bone in the jaw persisting for >8 weeks in patients without prior radiation to the jaws.5 AAOMS recommends that ONJ be managed conservatively with antibiotics, oral rinses and limited debridement. More aggressive therapies such as bone resection may be needed in patients with more advanced stages of ONJ. These approaches are summarized in Table 1 & 2. The conservative treatment of ONJ has been extensively reviewed and will not be discussed in details here.6 Let us say that, in addition to antibiotics, antiseptic rinse, local debridement, and the use of low level laser irradiation might improve the rate of overall response.7 These observations have been confirmed by a systematic review suggesting that combined treatment with antibiotics, minimally invasive surgery and low level laser therapy in the early stages of the disease might be helpful.8 Other adjunctive approaches to the “standard” treatment such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy, teriparatide, platelets-rich plasma, and others have been recently reviewed and it was concluded to a lack of evidence for the use of these treatments.9

Stage |

Description |

0 |

No clinical evidence of necrotic bone, but nonspecific clinical findings, radiographic changes, and symptoms present |

1 |

Exposed and necrotic bone or a fistula that probes to bone in asymptomatic patients with no evidence of infection |

2 |

Exposed and necrotic bone or a fistula that probes to bone, associated with infection, evidenced by pain and erythema in region of exposed bone with or without purulent drainage |

3 |

Exposed and necrotic bone or a fistula that probes to bone in patients with pain, infection, and ≥1 of the following: exposed and necrotic bone extending beyond the region of alveolar bone (i.e., inferior border and ramus in mandible, maxillary sinus, and zygoma in the maxilla), resulting in pathologic fracture, extraoral fistula, oral antral/oral nasal communication, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border of the mandible of the sinus floor |

Table 1 AAOMS Staging for MRONJ.

AAOMS: American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; MRONJ: Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

Bronj Stage |

Description |

Treatment Strategies |

At risk category |

Patients who have been treated with either oral or IV bisphosphonates or denosumab |

No treatment |

Patients education |

||

Stage 0 |

No clinical evidence of necrotic bone, but non-specific clinical findings and symptoms |

Pain medications and antibiotics |

Stage I |

Bone exposure with non-symptomatic lesions ; absence of infection |

Add topical antiseptic therapy |

Stage II |

Bone exposure with pain, infection and swelling |

Oral antibiotics – antibacterial mouth rinse – pain control |

Superficial debridement to relieve soft tissues irritation |

||

Stage III |

Bone exposure, pain, inflammation, maxillary sinus involvement, cutaneous fistulas and/or pathological fractures |

Antibiotic therapy, pain control, and antibacterial mouth rinse |

Surgical debridement and resection as clinically indicated |

Table 2 Clinical classification of BRONJ by Ruggiero et al. [5] and successive modifications by AAOMS 2009.

A recent systematic review of the therapeutically approaches in ONJ has suggested that the overall outcome results (for every disease stage) were the highest when patients were treated with extensive surgery or extensive laser assisted surgery.10

Silva et al.11 recently reported on the surgical management of bisphosphonates-related Osteonecrosis of the jaws. A variety of surgical approaches was found in their review (debridement, bone resection, bone reconstruction) as well as various adjunctive therapies (hyperbaric oxygen, laser therapy, growth factors, ozone…). Considerable differences were found between these studies and it was concluded that “clinical studies with larger number of patients and longer follow-up are required to provide best information for each surgical treatment modality…”.

Oncology aspects

Mrs S.L. was a 51-year-old lady, without significant medical history, when she received in 2009 a diagnosis of breast cancer that was already metastatic at the time (metastases in bones and liver). Because the tumor was strongly expressing hormonal receptors, she was treated with tamoxifen, gosereline and IV zoledronic acid as well as radiotherapy (9Gy) on a painful hip lesion. The patient remained asymptomatic with a normalized CA15-3, until January 2011 when a progression of the breast tumor was observed; the patient declined a mastectomy. At the same time, the liver and bone metastases were progressing and the CA 15-3 was 364U/ml. An ovariectomy was performed and letrozole was started. By the end of 2012, a new progression (liver and bone) was documented; the patient was switched on fulvestrant and denosumab. In June 2014, the patient was still in remission but complained of mandibular pain; denosumab therapy was discontinued (see Stomatology aspects). In May 2015, there was a progression within the breast as well as for the liver and bone metastases. Therapy was changed to exemestane plus everolimus, with a favorable response; this therapy is still continued (May 2016).

Stomatology aspects

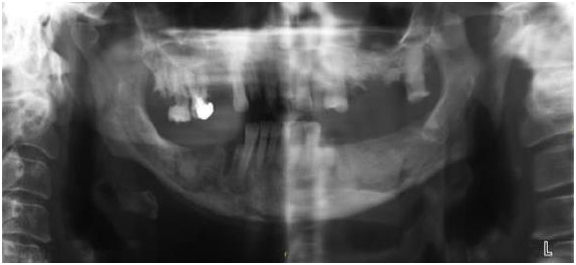

The first oral complaints appeared in June 2014; the patient reported mandibulary pain on the right side. Examination showed an abscess on 44 (right first pre-molar), which was extracted in November 2014. Denosumab was discontinued. Healing was very slow and incomplete. In April 2015, an external fistula with purulent discharge appeared at the inferior portion of the chin; intra-oral examination showed exposed mandibulary bone and loose teeth with an overall bad oral hygiene. Panoramic X-ray showed mandibulary Osteonecrosis involving both sides of the mandibulary symphysis (left 34-35) and right (45-46) with a fracture of the jaw (Figure 1). Therapy with amoxicillin (orally) and H2O2 rinses was started. In July 2015, the situation was unchanged but a large abscess had appeared under the chin; a surgical drainage was undertaken; amoxicillin and H2O2 rinses were continued. In October 2015, the situation was unchanged and the same therapy was continued; at the same time the patient was receiving everolimus, in addition to exemestane and extensive aphtosis was successfully treated with low level laser therapy. Because the stage III mandibulary Osteonecrosis was still progressing with extensive bone necrosis and multiple external fistulae, in spite of continuing therapy with various antibiotics, the decision to perform a wide resection of the lesions was taken in April 2016, following extensive discussion between the patient, the oncologist and the oral surgeon.

Figure 1 Mandibular osteonecrosis involving both sides of the mandibular symphysis (March 30, 2015).

Indeed, proposing to our patient a major respective and reconstructive surgery that might be curative for her Osteonecrosis was a major and difficult decision given the post-operative morbidity (tracheotomy, enteral nutrition, prolonged hospitalization, etc.), the always possible (although unlikely) failure of the procedure and the metastatic breast cancer for which, in spite of the present control, the long term prognosis was relatively poor. All these issues were explained and discussed with the patient. The main reason for her to accept the procedure was the importance she was putting on her external and feminine look, which she wanted to be preserved as much as possible, as well as her overall quality of life, namely normal eating. These considerations balanced for her the risk of surgery and the context of metastatic disease.

Operative procedure

Phase 1: tracheostomy: tracheal incision and insertion of a laryngo flex n°8.

Phase 2: resection of necrotic teeth (35 up to 48) and bone and neck dissection for exposure of the neck vessels. Cervicotomy on the right side up to the submandibular level and exposure of the right facial artery and vein as well as the right external jugular vein in preparation for micro-anastomosis.

Phase 3: preparation of the left fibula free flap. Preparation of the vessels: tibial artery and 2 tibial veins.

Phase 4: clamping the peroneal pedicle and mounting the flap with adaptation of the bone pieces to rebuild the angle of the mandibulary symphysis and osteosynthesis. Micro-anastomosis of the tibial artery and left facial artery as well as the tibial veins to either the left facial vein or the left external jugular vein.

Phase 5: closing the head and neck field, suturing the skin paddle to the mouth floor and vestibule; revision of homeostasis and setting two suction drains (right and left). At the left leg level, placement of two suction drains (superficial and deep); suture of muscles, and fascias; skin staples.

Phase 6: replacement of laryngo-flex by Shiley 8.0 and placement of a naso-gastric tube.

Figure 2 shows the respected portion of the mandibulary bone and Figure 3 shows the reconstructed mandible and Figures 4 & 5 the end cosmetic result. At the present time (9 months after the procedure), the patient’s metastatic disease is still under control with hormone therapy. After a smooth post-operative course, her maxillary bone is healed and she is being prepared to receive dental implants (Figure 4).

ONJ is a relatively rare but serious complication of bisphosphonates (and denosumab) therapy.3 Older guidelines recommend that surgery should be deferred as long as possible.6 Such an attitude has been supported by international and national reviews.12,13On the other hand, others, like Carston, believe that segmental resection of the mandible and partial maxillectomies; in order to achieve vital bone margins are crucial for the management of ONJ.14 The choice between conservative treatment and surgery is thus a major issue. Recently, Silva et al.11 reported a literature review on surgical management of ONJ; they concluded that, although there well-documented reports of successful surgical therapy of ONJ, considerable differences existed regarding sample size, surgical modalities and outcomes.11

In order to try and clarify these issues, we reviewed recently published studies of surgical management of ONJ. We concentrated on papers published during the last 5 years (in order to maintain homogeneity in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures) and involving more than 100 patients (in order to benefit from sufficient clinical expertise).

Mücke et al.15 examined the success of resection of ONJ prospectively in 108 patients,15 10 of whom were managed only conservatively. They concluded, from multiple logistic regression analysis that the type of treatment (with a lower recurrence rate for surgery), the extent of surgical treatment (better outcome in larger resections) and the number of debridements were significantly and independently associated with a lower rate of recurrence of ONJ. The overall success rate (lack of recurrence was 71.3% in the surgically treated patients).

Eckardt et al.16 analyzed retrospectively 142 patients with ONJ referred to a single institution,16 86% of whom had a surgical approach (sequestrectomy with local or myofascial flap closure, marginal bone resection and segmental resection with or without reconstruction); additional surgical interventions were needed in 40% of these patients. The patients who received only conservative therapy (14%) with antibiotics and oral irrigation with chlorhexidine did apparently well, but no details about the initial stage of their disease was provided. No clear recommendation was made given the lack of consensus on the extent of surgical resection and reconstruction.

Graziani et al.17 conducted a retrospective cohort multicenter study of 347 cases of ONJ.17 Improvement was noted in 59% and 11% showed worsening. Improvement was observed in 49% of cases treated with local debridement and in 68% of cases treated with resection. As shown in Table 3, the positive outcome was 61% in patients with stage 2 and 8% in those with stage 3; patients with stage 1 responded in 31%, but no details were provided regarding the extent of the surgical procedures in those 3 groups, which was based “on the personal experience of the surgeon”.

Total Number of Patients |

108-347 (Total 1,459) |

Mean age (years) |

62-69 |

Male/female ratio |

25-33/67-75 |

Underlying cancer (%) |

70-100 |

Mandibular location (%) |

58-75 |

Maxillary location (%) |

20-32 |

Duration of exposure to bisphosphonates (months) |

16-51 |

Triggering event (trauma, surgery) (%) |

57-99 |

Initial stage 1 (%) |

13-28 |

Initial stage 2 (%) |

28-62 |

Initial stage 3 (%) |

Oct-41 |

Operative management (%) |

53-100 |

Non operative management (%) |

0-47 |

Response in stage 1 (%) |

16-31 |

Response in stage 2 (%) |

22-67 |

Response in stage 3 (%) |

Aug-40 |

Response to operative treatment |

59-87: total 938 patients/1,204 (77%) |

Response to non-operative treatment |

20-100: total 40 patients/250 (16%) |

Table 3 Range of results in 7 recently published studies (2011-2015) including each more than 100 patients each after surgical resection.

Vescovi et al.18 reported on 151 treated in a single center.18 The authors used a specific classification of ONJ (G1-G5) with clearly defined therapeutic approaches for each of them, which made the translation into the AAOMS staging delicate. Nonetheless, they found better results with the surgical approach (87% of responses) than with the medical treatment (26%) that was used in the least extensive ONJ. The authors also stated low level laser therapy could improve the results. They also used surgical laser (e.g.: YAG laser 2940mm) for the treatment of necrotic bone in addition to resection and concluded that the introduction of laser-assisted and surgical approaches improved the therapeutic results.

Holzinger et al.19 reported on 108 patients with ONJ, among which 88 could be followed in the long term.19 Surgery significantly down staged ONJ for patients with initial stage 2 and 3; overall, the response rate was 59%. They found also that patients with underlying malignant disease and those with a triggering factor for ONJ had a poorer prognosis. Patients with ONJ in the maxilla required earlier and more recurrent surgery than those with ONJ in the mandible.

Franco et al.20 published a long-term follow-up of 266 patients in a single institution.20 They found an overall response rate (lack of recurrence) of 85% in patients with an underlying neoplastic disease and 94% in osteoporotic patients. The authors insisted on the importance of dimensional staging for the choice of surgery and the possible role of piezosurgery and LLLT in improving the results.

Finally, a last study by Ruggiero et al.21 involved a retrospective cohort study of 337 patients. Patients with ONJ who presented with a less severe disease or who underwent operative treatment were more likely to have complete healing; the overall success rate for operated patients was 79% and patients who had received operative care were 28 times more likely to have a positive outcome. Underlying neoplastic disease was found to be a negative prognostic factor. That study is the only one in which 23% of the patients had been treated with denosumab; in all the other studies, only bisphosphonates had been used.

The overall results of these 7 studies are shown in Table 3 which indicates the ranges of results observed. The total population surveyed in those 7 studies includes 1,459 patients with a mean age of 62-69 years and a male/female ratio of approximately 1 out of 3. Most patients (70%) had an underlying neoplastic disease and have been exposed to bisphosphonates for prolonged periods (16-51 months). ONJ was located to the mandible in most patients (50-75%) and was preceded by a triggering event (trauma, surgery) in most patients (57-99%). Initially, stage 1 was diagnosed in 16-31% of the patients, stage 2 in 22-67% and stage 3 in 8-40%. Operative management was applied in 53-100% of the patients and non-operative treatment in 0-47%; response after surgery was seen in 59-87% of the patients (actually 938 patients out of 1,204(77%) responded). Non-operative treatment was successful in 20-100% of the patients (actually 40 out of 250(16%) patients responded). The highest range of response (overall) was seen in patients with stage 2 disease (22-67%). These results should be put into the context of what has been published so far. Migliorati et al.2 reported percentages of healing from 17% for medical therapy or surgical debridement to 46% for free flap or surgical resection procedures.2 Clearly, our review of recently published data supports the use of a surgical approach, a view supported by Stockman et al.22 in a recent paper.22

Our analysis has several limitations. Firstly, even if one selects recently published relatively large series, the population of patients remains heterogeneous in terms of prognostic factors, co-morbidities, staging and surgical interventions, which are often inadequately described. In addition, the precise relationship between the stage of ONJ and the elected treatment is often not stated and the operative modalities were applied without a specific protocol. Moreover, the non-operative approach is not uniform between these studies and various additional approaches such as low level laser therapy were used in some instances. Finally, there is no unique way to assess the response to therapy: although “lack of recurrence” is often cited as the criteria of response, other evaluations of response have been used as well. Therefore, our conclusions about the potential efficacy of surgical interventions (77% of favorable responses) must be tempered by these caveats. It remains that early surgical interventions might prevent catastrophic progression of ONJ such as seen in our patient. Further progresses in the management of ONJ should require multi-centre cooperation with the use of strict diagnostic and therapeutic protocols.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Massaut, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.