eISSN: 2373-6372

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 4

1Department of Gastroenterology Physician, Lauro Wanderley University Hospital, Brazil

2Department of Pathology, Paraíba Federal University, Brazil

3Department of Gastroenterology, Paraíba Federal University, Brazil

4Department of Surgery and Anatomy, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Correspondence: Mônica Souza de Miranda Henriques, Rua Rita Sabino de Andrade, 354, Bessa, João Pessoa, Brazil, Tel +5583991125527

Received: June 26, 2020 | Published: July 27, 2020

Citation: Filho AFM, Nóbrega FJF, Paz AR, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infection mimetizing pancreatic pseudotumor in immunocompetent patient. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2020;11(4):130-132. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2020.11.00428

Strongyloides stercoralis is one of the most prevalent species of parasites in the world and is considered endemic in Latin America. Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal parasite, transmitted by soil and highly prevalent in hot regions with inadequate sanitation. Commonly reported symptoms of strongyloids infestation include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, hives, and "larva currens". In the present report, a man without comorbidities, with no immunosuppressive conditions, developed an exuberant clinical picture, whose infection spread in a way to cause uncommon clinical manifestations, such as intestinal ulcerations, running with duodenal stenosis and pancreatic pseudotumor. The diagnosis was made by computer tomography and histopathological examination of duodenal lesions. After the antiparasitic treatment, the patient evolved with complete remission of gastrointestinal symptoms, of imaging findings and with adequate nutritional recovery. Although pancreatic involvement related to Strongyloides stercoralis infection is a rare condition, should be considered as a diferential diagnosis in pancreatic pseudotumors.

Keywords: strongyloidiasis, pancreas, pseudotumor

Strongyloides stercoralis is a nematode intestinal parasite, transmitted by soil and highly prevalent in hot regions with inadequate sanitation.1,2 It is estimated to have between 200 and 370 million cases worldwide.3 Commonly reported symptoms of strongyloid infestation include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, hives, and "larva currens". While infection is asymptomatic in half cases, it can be potentially fatal in immunocompromised patients.4-6 We present a rare case of strongyloidiasis in an immunocompetent patient, whose extensive inflammatory process simulated the presence of a pancreatic tumor.

A forty three-year-old male admitted with diffuse and intermittent abdominal pain, associated with nausea, vomiting and estimated weight loss of 14 kilos in 2 months. He also referred a change in intestinal habit, with episodes of diarrheal evacuations of large volume (average 4 times a day) with feces of pasty consistency and without abnormal elements. He denied the use of continuous medications. His mother was treated for tuberculosis 20 years ago. Alcoholism and smoking were abandoned. At clinical examination, he presented at a regular condition, with BMI = 18.2 kg/m2, blood pressure 110 x 70 mmHg, tachycardic, anicteric, afebrile, hypochoric, dehydrated and referring diffuse abdominal pain.

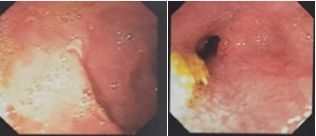

Among laboratory tests, increased levels of CA 19-9 (68.5 U/mL), normocytic and hypochromic anemia (Hb = 10.2 g/dL), besides the absence of eosinophilia, stands out. Enzymes and liver function, amylase, lipase, serologies for viral hepatitis, HIV, VDRL and fecal propaedeutic tests all within normality. Chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasonography also showed no changes. Actives duodenal bulb ulcers (Sakita's A1 classification) and partial duodenal stenosis at second duodenal portion were found in upper digestive endoscopy (Figure 1). Colonoscopy demonstrated aphthoids ulcers in descending colon (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Evidence of upper Digestive Endoscopy with active duodenal bulb ulcers (Sakita's A1 classification) and partial duodenal stenosis at second duodenal portion.

Histopathology revealed chronic duodenitis, eggs and adult forms of Strongyloides stercoralis, ulcerated chronic colitis in mild activity, with microabscesses of crypts and architectural glandular alterations. No signs of malignancy (Figures 3 & 4).

Figure 3 Histopathological examination of duodenal ulcers with chronic duodenitis, eggs end some adult forms of Strongyloides stercoralis, focis of ulceration and fibrino-leukocyte crust, without signs of malignancy - HE-200x.

Figure 4 Colonic mucosa with microabscesses of crypts (black arrow) and architectural glandular distortion (white arrow) - HE-200x.

Due to significant abdominal pain, associated with nausea and vomiting, an abdominal contrast computed tomography (CT) was performed. A nodulariform and hypodense area (1.5 x 1.2 cm) located in pancreatic uncinate process was found, with dilation of choledochus (9 mm) and main pancreatic duct (4 mm) (Figure 5). The patient underwent treatment for strongyloidiasis with albendazole 400 mg every 12 hours for 7 days, evolving with a complete remission of gastrointestinal symptoms and nutritional recovery. An abdominal nuclear magnetic resonance was performed 30 days after treatment and showed no pancreatic lesion.

Strongyloides are parasites of vertebrates, and the genus comprises more than 50 species.7 They infect different hosts, such as amphibians, birds and mammals, including humans. The latter can be infected by three different species of Strongyloides, named Strongyloides stercoralis, Strongyloides fuelleborni and Strongyloides fuelleborni kelleyi.8 Strongyloides stercoralis is the most prevalent species in the world and is considered endemic in Latin America.9

Most immunocompetent infected hosts are asymptomatic, that is why it’s true prevalence may be underestimated.10 After the establishment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection, the immune system tries to contain the infection constantly. However, in the presence of specific risk factors, such as the use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants, and coinfection by HTLV-1, severe forms of infection can appear.11–13

In the present report, a man without comorbidities, using no immunosuppressive medications, and with HIV and HTLV-1 negative serologies, developed an exuberant clinical picture, whose infection spread in a way to cause uncommon clinical manifestations, such as intestinal ulcerations, running with duodenal stenosis and pancreatic pseudotumor. Although there is no gold standard for diagnosing S. stercoralis. Diagnostic methods range from simple stool examination to serological tests and molecular techniques based on nucleic acid amplification. However, all of these techniques have problems with sensitivity, specificity, or availability in endemic areas. It has been shown that a single stool examination fails to detect larvae in up to 70% of patients. Repeated examinations of stool specimens are required to improve the chances of finding the excreted forms. Although serologic tests are useful, limitations concerning cross-reactions still remain. Serum antibody levels may not differentiate between active infection and suspected cases or false positive serological results. Immunological tests are not able to distinguish cases with positive parasitological tests from those with negative stool tests for S. stercoralis.10 Strongyloidiasis can involve any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. The most common endoscopic findings are ulceration, duodenal spasm, bleeding, mucosal edema, thickened duodenal folds, or brown discoloration of the mucosa. It was of great importance in this case, since the patient had normal stool tests and no peripheral eosinophilia.

The presence of architectural glandular alterations and microabscesses of crypts in the histopathological examination of the descending colon ulcer, associated with partial stenosis of the duodenum, mimicked inflammatory bowel disease. The dramatic response to the use of albendazole and the presence of similar microscopic changes already described in the literature in strongyloid infection made such a diagnostic hypothesis unlikely.14

Pancreatic involvement related to Strongyloides stercoralis infection is rare. Five cases of pancreatitis have been reported in the English and Spanish literature.10,15–18 Association with pancreatic cystoadenocarcinoma and pancreatic head mass have also been reported.19,20 Faced with the finding of a nodulariform lesion in an uncinate process associated with high levels of CA 19.9, a further etiological investigation of the condition became mandatory.

CA 19-9 is currently the most used biomarker for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in symptomatic patients. However, it is worth remembering that serum levels of CA 19-9 may also be elevated in a variety of nonpancreatic neoplastic conditions, as well as in benign conditions, such as pancreatic inflammatory processes, heart failure, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis and diverticulitis.17–20 The explanation for the increase in CA 19-9 levels, observed in this case, was due to the involvement of the duodenal ampoule and main pancreatic duct, leading to intense inflammation and edema. However, the possibility of an expansion process was still real.

Currently, three drugs are approved for the treatment of strongyloidiasis: Albendazole, Mebendazole and Ivermectin. Albendazole belongs to a group of anthelmintic drugs benzimidazole, which act on the microtubular system of the parasite. The usual oral dose of albendazole is 400 mg twice a day for three days and can be up to seven times as reported.12 Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging performed 30 days after treatment showed no signs of pancreatic disease.

We present an uncommon case of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an immunocompetent adult man associated with pancreatic pseudotumor. The infection was not associated with eosinophilia, or with findings of parasitic elements in stool tests. The diagnosis was made by histopathological examination of duodenal lesions. After the antiparasitic treatment, the patient evolved with complete remission of gastrointestinal symptoms, of imaging findings and with adequate nutritional recovery.

No conflict of interest to disclosure.

Professor Juliene Paiva de Araújo Osias for translation and reviewing process.

None.

©2020 Filho, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.