eISSN: 2373-6372

Case Report Volume 7 Issue 6

1Pakistan Health Research Council (PHRC), Pakistan

2Consultant Radiologist, Islamabad, Pakistan

Correspondence: Hassan Mahmood, Medical Officer for Viral Hepatitis, Pakistan Health Research Council (PHRC), Islamabad, Pakistan Independent Consultant, Cooperative Agreement, TEPHINET-CDC, Pakistan, Tel +92-300-5416871

Received: September 20, 2017 | Published: October 30, 2017

Citation: Mahmood H, Raja R (2017) Risk Factors of Hepatitis C in Pakistan. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access 7(6): 00259. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2017.07.00259

Pakistan is facing an epidemic of hepatitis C in the country. Almost 10 million people are affected with hepatitis C in Pakistan. Most of the people are unaware of their health status because the disease is asymptomatic in its initial course. The major causes of disease spread are unsafe blood transfusions, re-use of therapeutic syringes, unsafe medical and surgical practices, shaving at barbers, ear and nose piercing. Pakistan is a middle income country and has limited resources. Therefore, it should more focus on devising and implementing the effective preventive strategies to reduce the disease burden of hepatitis C.

Keywords: Prevention; HCV; Pakistan; Risk factors; Prevalence; Disease patterns

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is major causes of infectious disease morbidity and mortality globally, most morbidity and mortality is due to sequel of chronic infection such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and decompensated cirrhosis [1]. WHO estimates that 170 million people are living with chronic HCV worldwide [2,3]. Hepatitis C is estimated to cause 366,000 deaths annually [4].

Pakistan has one of the world’s largest burdens of viral hepatitis [2]. According to a National Hepatitis Survey, approximately 08 million people are living with HCV in Pakistan [5]. Most of the people infected with HCV are not aware of their infection status resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment [6]. Delayed diagnosis can result in sequel such as cirrhosis, decompensated chronic liver disease (DCLD) and HCC, ultimately increasing the disease burden for a poor resource country like Pakistan [6].

Many studies have been conducted to evaluate risk factors for transmission of HCV. One study conducted in 1994 in Pakistan found that household members who had received four or more injections per year have 9–11 times greater chance of being infected with HCV [7]. Bari et al. [8] found that increased use of unsafe injections and receiving shave from barbers are significant risk factors [8]. Shah et al. [9] found that blood transfusions, surgical procedures, therapeutic injections by quacks, dental procedures, and shaving from barbers were important risk factors for hepatitis C [9]. Rehman et al. [10] showed that health care workers (HCW) are at high risk of suffering from hepatitis [10]. Akhtar S et al. [11] determined that patients with history of hospitalization or those who have received multiple therapeutic injections are at high risk of getting the disease [11].

WHO named HCV as a “viral time bomb” because 170 million people are infected with HCV infection worldwide [12]. Out of these, 130 million are chronic carriers of the disease and at risk of developing complications of infection particularly chronic liver disease (CLD), such as chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis hepatocellular carcinoma [12]. HCV seroprevalence was found to have a range from 1 % to 12% in South Asia [13,14]. There are three to four million incident cases annually and 70% of them are at risk of developing chronic hepatitis. In developed countries, two third of liver transplant and 50-76% of liver cancers are caused by HCV infection [12]. According to World Health Statistics 2008, liver cirrhosis was the 18th commonest cause of mortality worldwide and if it remains uncontrolled, by 2030, it will become the 13th commonest cause of mortality [15].

It is said that about 20 to 30 % patients with chronic HCV infection will develop cirrhosis over a period of 20 years. Thus the quality of life of these patients is greatly impaired due to the complications caused by cirrhosis like; encephalopathy, ascites, coagulopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal bleeding and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Some of HCV related mortality statistics by worldwide region are as follows (Table 1) [15].

Region |

No. of HCV Related Deaths in 2002 |

Africa |

8,000 |

America |

7,000 |

South East Asia |

14,000 |

Europe |

4,000 |

Eastern Mediterranean |

5,000 |

Western Pacific |

14,000 |

Table 1: HCV related mortality statistics worldwide.

Global Prevalence of HCV infection

Prevalence of HCV varies in different parts of the world because of different medical, social, cultural, political and behavioural practices. Following Table 2 shows HCV prevalence submitted to WHO by different countries [16].

Region |

Total Population (Millions) |

Infected Population (Millions) |

Prevalence (%) |

Africa |

602 |

31.9 |

5.3 |

America |

785 |

13.1 |

1.7 |

Eastern Mediterranean |

466 |

21.3 |

4.6 |

Europe |

858 |

8.9 |

1.03 |

South-East Asia |

1500 |

32.3 |

2.15 |

Western Pacific |

1600 |

62.2 |

3.9 |

Total |

5811 |

169.7 |

18.7 |

Table 2: Global prevalence of HCV.

Incidence of HCV

Incidence rate of HCV fluctuates greatly owing to the asymptomatic and latent course of infection [17]. Much less data are available about the incidence of HCV infection because of silent nature of the disease [17]. A difficulty in establishing the incidence of HCV infection leads to difficulties in monitoring the effectiveness of primary preventive measures since prevalence data are not enough for this. However, the reported incidence rate for HCV seroconversion is 11-29/100 persons/year [18]. Seroconversion is termed as the development of detectable specific antibodies to microorganisms in the blood serum as a result of infection. HCV is found in the blood at low levels and routine serological tests are not very reliable to detect the disease [19]. Therefore, more sensitive and specific tests like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are required to confirm the diagnosis [19].

Demographic features of Pakistan

Pakistan has a population of 173 million people with the highest fertility rate of more than four children per woman [2,20]. It is a developing country with population of low socioeconomic status and poor education. According to human development index of the United Nations, it was ranked 134th out of 174 countries [20]. It covers an area of 796,096 sq. Kilo-metres and is divided into four provinces (Figure 1); Punjab, Sindh, Khyberpakhtunkhwa (Previously known as NWFP), and Balochistan as well as federally administered areas including the capital (Islamabad) [2].

Current situation in Pakistan

HCV infection is endemic in different parts of the world [5]. However, prevalence and incidence of HCV considerably changes with geographic and temporal variation [21]. Although HCV is becoming a major threat to public health, yet there is very limited information about prevalence and incidence of HCV in Pakistan as compared to most of the developed countries (e.g.UK and USA) of the world where there is enough information about the prevalence and incidence [22]. However, attempts have been made to measure seroprevalence of HCV in Pakistan for example; it is found that frequency of HCV infection ranges from 0.4% in Karachi (Sindh) to 33.7% in Jarwar. The mean frequency is 4.7% with 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.6 - 4.8 [12]. It is more common among males. In males it mostly occurs between 40-49 years of age while in females between 50-59 years of age.

Different studies show that therapeutic use of contaminated needles in medical care, unsafe blood transfusion; intravenous drug abuse, non sterile surgical and dental procedures are major factors responsible for transmission of HCV [23]. Prevalence of HCV varies in the four provinces of Pakistan being highest in Punjab. According to a recent survey conducted by Pakistan medical and research council, the prevalence of HCV in four provinces of Pakistan is as follows; [1,24]

Why is it a major public health problem in Pakistan?

More than 10 million people are infected with HCV in Pakistan [25]. Data suggest that 60-70 % patients who present with chronic liver disease (CLD) are anti HCV positive [26]. Nearly 50 % patients with liver cell carcinoma or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are anti HCV positive [27].

Major factors responsible for this high disease burden in Pakistan are;

In developed countries, more concerns and efforts have been made to control the transmission of HCV infection. As a result the incidence and prevalence of HCV infections has decreased for example prevalence of HCV infection in England is 0.4% [37]. But it still remains a big problem in developing countries like Pakistan because of factors mentioned above.

Common risk factors for HCV transmission in Pakistan

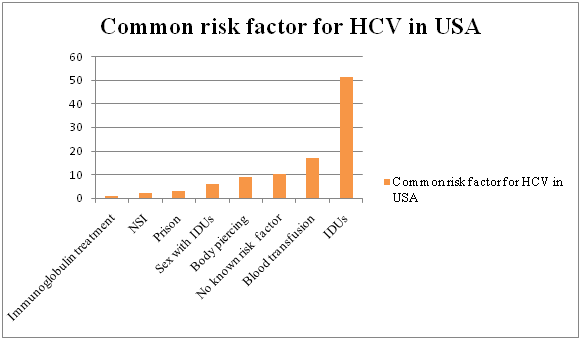

Risk factors for HCV transmission in Pakistan are different as compared to the developed world [38]. In developed countries, IDUs are recognised as major risk factor for transmission of HCV infection [39]. Murphy et al. [39] conducted a study in USA and found IDUs as a major risk factor for HCV transmission with a seroprevalence of 51%. Other important risk factors were blood transfusions (17%), no known risk factor (10%), body piercing (9%), sex with IDUs (6%), prisons (3%), needle stick injuries (2%) and immunoglobulin treatment (1%) as shown in Figure 2 [39].M

Figure 2: Prevalence (%) of HCV in USA as per risk factors showing risk factors on horizontal axis and percentage of prevalence of HCV on vertical axis.

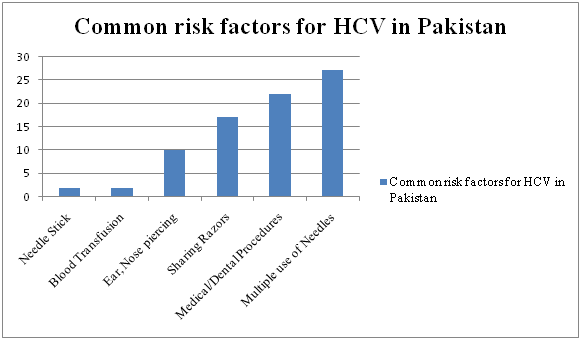

But this is not the case in Pakistan. Several studies have shown that multiple and unnecessary use of injections, unsafe medical/surgical procedures, use of contaminated razors by barbers, ear, nose piercing, blood transfusions and needle stick injuries (NSI) are major risk factors for HCV infection in Pakistan.29 Following Figure 3 shows the prevalence of HCV infection in Pakistan due to different risk factors ranging from 27% because of multiple use of needles to 2% due to needle stick injuries [29].

Figure 3: Prevalence (%) of HCV in Pakistan as per risk factors, showing risk factors on horizontal axis and percentage of prevalence of HCV on vertical axis.

Reuse of syringes for therapeutic purposes was found to be the most significant factor associated with the transmission of HCV infection [42]. A large number of patients, almost 26% got the infection because they were administered intravenous injections from the GP clinics, which were recognized for reusing the syringes [29]. People who got the injections were more likely to get HCV infection as compared to those who did not get the injections as shown in Table 3 [43]. Also, household members who received more than four injections per year were 11.9 times more likely to be infected than others with a p value of 0.02 [7].

Average No. Of Injections Annually in Last 10 years |

HCV Positive |

HCV Negative |

Odds Ratio |

1 |

0 |

8 |

0.00 |

2-4 |

2 |

13 |

1.54 |

5-9 |

2 |

8 |

2.50 |

>10 |

9 |

13 |

6.92 |

Table 3: Relationship between therapeutic injections and HCV infection.

Several studies show that factors responsible for unsafe medical and surgical practices are: poor knowledge [45], poor skills [46], lack of riskawareness [47], variance of interests [45], not wanting to offend patients [48], lack of equipment [49] and time, uncomfortable personal protective equipment, inconvenience, work stress and perceiving a weak organizational commitment to safety climate [45,46,49].

In Pakistan, poor qualifications, lack of training, lack of knowledge, absence of a system for prevention of blood borne pathogens and post exposure prophylaxis at health care facilities are the most common factors responsible for increased transmission of HCV infection [31].

Natural history of the disease

Natural history of HCV is not completely understood as the disease may take different courses among infected individuals [60]. HCV can lead to;

The appearance of anti HCV antibody may take 5 to 12 weeks after exposure but HCV RNA can be detected as early as 1 to 2 weeks following exposure [60].

Chronic effects of HCV infection

As mentioned earlier, chronic infection by HCV causes slow progression of liver disease that leads to liver cirrhosis, CLD and hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC) over a period of 30 years [61]. Chronic liver hepatitis is the 5th most common cause of death worldwide [62]. The mean seroprevalence of HCV infection in the above mentioned diseases is shown in the following Table 4 [12].

Type of the Disease |

Mean Seroprevalence of HCV Infection (%) |

Liver cirrhosis |

44.9 |

Chronic liver disease (CLD) |

52.9 |

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) |

50.6 |

Table 4: Prevalence of HCV in patients with liver diseases.

Above table shows the high prevalence of HCV in different hepatic (Liver) diseases. These diseases are the end stage of HCV infection and can lead to many complications which cause a great number of deaths in Pakistan [12]. The mean age for developing CLD is lower in Pakistan than any other developed country, revealing that individuals are infected at an early age in this region of the world [63]. Thus, if patients are provided proper preventive measures and timely diagnosis, they can be saved from such complications.

Reducing the incidence of HCV infection without preventive interventions, can be a major public health challenge [64]. Therefore, more focus should be on primary prevention to control the disease burden of hepatitis C [65].

Majority of patients only discover that they are infected with HCV, when the disease expresses itself after a long period of time with all its complications. At that point of time, majority of the patients are beyond the scope of treatment and cannot even bear the expenses of treatment. Therefore, developing effective primary preventive measures is vital in order to prevent and control disease transmission.

None.

None.

©2017 Mahmood, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.