eISSN: 2373-6372

Mini Review Volume 7 Issue 5

Department of Internal Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

Correspondence: Fady Maher Wadea, Assistant professor of Internal Medicine department, Gastroenterology and Hepatology division, faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt

Received: May 22, 2017 | Published: September 7, 2017

Citation: Wadea FM (2017) Insights to Indications and Harm of Proton Pump Inhibitors Usage in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access 7(5): 00250. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2017.07.00250

P.P.I therapy is often used in patients with cirrhosis, sometimes, in the absence of a specific indication (e.g.: acid related diseases), there are conflicting reports for their use in cirrhotic patients. The dosage of most PPIs should be reduced in cirrhotic as they are metabolized by the liver and associated with adverse effects of prolonged use.

Keywords: proton pump inhibitors, liver cirrhosis, peptic ulcer, H. pylori, esophageal band ligation

PPI, proton pump inhibitors; EVS, esophageal variceal sclerotherapy; EVL, esophageal variceal ligation; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; CDI, clostridium difficile infection; PHG, portal hypertensive gastropathy; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; LES, lower esophageal sphincter

A significant proportion of cirrhotic patients are prescribed for PPIs.1 The indication for PPI prescription in many of these patients is weak or unclear,2,3 in their study, Bajaj et al. Found that half of their patient population did not have either an established or appropriate indication for PPI therapy usage.4 Proton pump inhibitors facilitate bacterial overgrowth in G.I.T and may promote serious infections leading to liver function deterioration and increasing mortality so, a careful use of PPI in cirrhotic should be announced, especially when they are used away from hard indications. We aimed to review strict indications for their use in this group of patients.

Esophageal varices

EVS and EVL procedures produce local complications such as esophageal ulcerations, strictures, and perforations.5 Uncontrolled non-randomized studies showed that PPI may have a role in the prevention and healing of post-EVS ulcerations6 and in prevention of gastro esophageal reflux produced by esophageal wall motor dysfunction.7 Pantoprazole has been shown to reduce the size of ulcers in patients undergoing elective band ligation and PPI treatment is advisable in patients undergoing this procedure. A short course for 10 days post-EVL may be reasonable if we concern for ulcer healing. However, high-dose infusion (e.g., pantoprazole 8 mg/h) and prolonged use in the absence of endoscopic procedures is not supported by the literature and should be discouraged until evidence of benefit becomes available.8

GERD

Functional studies showed decreased LES function with low amplitude of acid clearance and primary esophageal peristalsis in cirrhotic patients with large varices.9 These phenomena could be due to a mechanical effect of the varices. Cirrhotic patients without EV have also esophageal motor disorders and mixed acid and bile reflux as the main pattern, whereas the cirrhosis itself is an important causative factor. It is unclear whether this might contribute to bleeding from varices.8 Data on management of GERD in cirrhosis are few, however, the indications of use for PPIs may remain exactly the same in patient with cirrhosis of the liver as general population for the treatment of erosive esophagitis, or in general the pathology secondary to gastroesophageal reflux of acid.10

Peptic ulcer and H. pylori infection

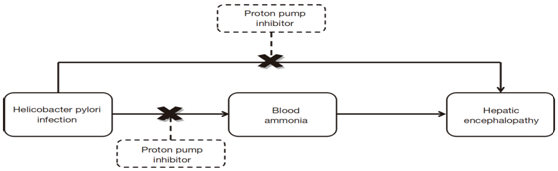

Prevalence of duodenal and gastric ulcers in patients with liver cirrhosis increases as the disease progress11 and this prevalence becomes higher in decompensated cirrhosis than in compensated cirrhosis.12 Currently, PPIs are the mainstay treatment option of peptic ulcers in the general population.13 Helicobacter pylori infection contributes to the development of hyperammonemia14 and subsequent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis .15. H. Pylori eradication has been improved by the use of PPIs-based triple therapy.16 Blood ammonia concentration was significantly reduced after PPIs-based triple treatment in cirrhotic patients.14,15 Therefore, it might be of value that PPIs can reduce the risk of hepatic encephalopathy development in cirrhotic patients infected with Helicobacter pylori .17

A meta-analysis done by Vergara et al.18 showed that Helicobacter pylori infection was a risk factor for developing peptic ulcers in cirrhotic patients.18 Similar observations were found in Calvet et al.19 study. Thus, Helicobacter pylori eradication with PPIs treatment may be necessary. If H. Pylori infection were an etiopathological factor implicated in digestive bleeding in cirrhosis, eradication of infection would decrease the risk of ulcer recurrence, however; other studies show conflicting results as regards no decreased risk of ulcer recurrence.17

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

Proton pump inhibitors, sucralfate, and histamine-2 receptor antagonists are not very effective at reducing bleeding from PHG because most patients with PHG already have hypochlorhydria.20 However, proton pump inhibitors may indirectly stop bleeding from the stomach by raising intraluminal gastric pH and thereby stabilizing blood clots.21,22 Additionally, patients whose bleeding were refractory to vasopressin benefited from omeprazole co-administration and vice versa.

Harms of P.P.I usage in cirrhotic patients

Harms unique to the liver: SBP and HE:8 PPI decrease gastric acid production and raise the pH of the stomach, elimination of the gastric acid barrier facilitates intestinal bacterial overgrowth. This increases the risk of translocation of gut bacteria to the mesenteric lymph nodes and from there to the blood and lymph with the end result is systemic inflammation, which is an important second hit-after the first hit, hyperammonemia-in HE development.23

PPIs promote the small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and altered intestinal motility, which might be the pathogenesis of SBP. Some evidence had shown that PPIs treatment was a predisposing factor for SBP in patients with cirrhosis which might be related to the dosage and duration of PPIs.24

Acute hepatitis: In patients with hepatic dysfunction, the pharmacokinetics of PPIs changes.25 Case reports of acute hepatitis in even subjects without previous liver disease have been reported for omeprazole, lansoprazole and recently pantoprazole. It is difficult to state whether the hepatotoxicity related to these drugs is a class effect due to the basic benzimidazole structure shared by these drugs. However, cross-hepatotoxicity between different PPIs has not been described.26

Harms occur in cirrhotic patients and general populations

Osteoporosis and bone fractures due to hypocalcemia. Infectious enteric complications, such as a twofold increased risk of Clostridium (CDI) difficile infection27 and a higher frequency of community .28 and ventilator acquired pneumonia.29 PPIs may contribute to deficiencies of B12, iron and magnesium, acute interstitial nephritis and rebound acid hypersecretion with drug cessation.30

Dosing of P.P.I in liver diseases

In the case of liver impairment, the Area Under the Curve for PPIs increases and their half-life becomes 4 h to 8 h greater,31 the risk of their accumulation increase. This effect was also seen with rabeprazole32 however; a dose reduction seems to be unnecessary with a 20 mg, once daily dose in patients with mild to moderate liver cirrhosis. When using other PPIs or rabeprazole at 40 mg/d, dose reduction is advisable (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Possible relationship between proton pump inhibitor and decreased risk of hepatic encephalopathy in H. pylori infected patients.17

YP2C19 is the main metabolic pathway for P.P.I, the affinity for different PPIs is different and rabeprazole is metabolized mainly by a non enzymatic pathway. There are two CYP2C19 phenotypes: extensive and poor metabolisers. Poor metabolisers have higher plasma levels of PPI, which could lead to higher efficacy, but also to potential adverse events. The effects of these genotypes varies according to the specific PPI used and in general is greater when using omeprazole decreasing progressively to lansoprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole and finally rabeprazole.33

The widespread prescription of PPIs in cirrhotic patients needs to be revised. PPIs can be used to effectively control the complications following endoscopic treatment for esophageal varices and reduce the risk of ulcers or hepatic encephalopathy related to the Helicobacter pylori infection or stabilization of blood clot in bleeding ulcer or PHG which are the potential indications. On the other hand, the use of PPIs may increase the incidence of serious adverse events as bone fracture, CDI, pneumonia, SBP and HE with long term use.

None.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2017 Wadea. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.