Case Report Volume 2 Issue 3

An unusual case of Esophageal Varies: “Downhill” type

Georges El Jammal

Regret for the inconvenience: we are taking measures to prevent fraudulent form submissions by extractors and page crawlers. Please type the correct Captcha word to see email ID.

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, UAE

Correspondence: Georges El Jammal, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, NMC Specialty Hospital, Dubai, UAE

Received: May 08, 2015 | Published: May 28, 2015

Citation: Jammal GEL (2015) An unusual case of Esophageal Varices: “Downhill” type.Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access 2(3):00040. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2015.02.00040

Download PDF

Abstract

Downhill esophageal varices is a rare condition, less common than the classical “uphill” varies characterized by the presence of esophageal varies in the absence of portal hypertension. Because of the rarity of this condition, there are no clear guidelines or recommendations regarding its management. This is a case of Downhill esophageal varies incidentally discovered during endoscopy.

Introduction

“Downhill” esophageal varices is a rare condition, less common than the classical “uphill” varices,1–4 it was first reported in 1964 by Felson and Lessure.5 Obstruction of blood flow through the inferior vena cava and/or its tributaries, forces the blood to find an alternative way back to the right heart. This is achieved through the portal circulation via the esophageal veins. The esophageal veins will have to accommodate the backflow of blood coming from the azygos, hemiazygos, superior intercostal, bronchial, and the inferior thyroid veins.

Case presentation

A 31 year old female presented to the Gastroenterology Clinic in 2009 for abdominal pain. Her past surgical history includes a successful renal transplant in 2006. Her past medical history includes renal insufficiency in 2000, managed with Dialysis until 2006, complicated by fistula thrombosis so multiple central lines were inserted. Other past medical history includes Lupus, High Blood Pressure, and Hypercholesterolemia. Her medical treatment included Amlodipine, Bisoprolol, Atorvastatin, Mycophenolic Acid, and Tacrolimus.

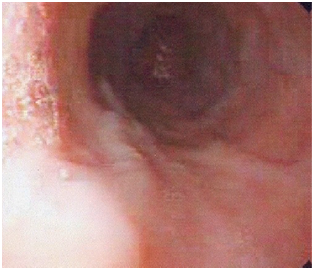

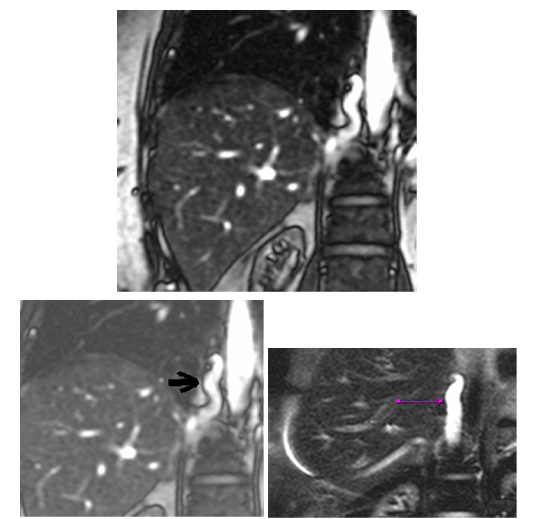

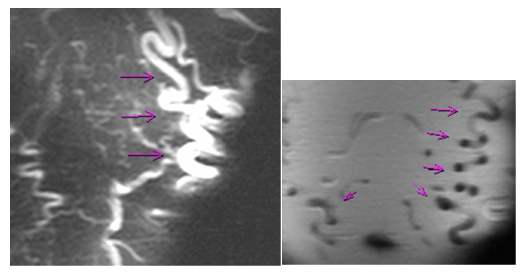

The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy Figure 1,2 revealed small and medium size esophageal varices in the upper and middle thirds of the esophagus, without red signs, and “snake skin” antritis. The presence of esophageal varies warranted a workup for portal hypertension. ALTS, Albumin, Bilirubin were normal. Ferritin was elevated (771 ng/ml), Transferrin saturation was 38%. Genetic test for hemochromatosis revealed heterozygous mutation on Cys 282Tyr and His 63Asp, and no mutation on Ser 65Cys. Ceruloplasmin, 24h Urine copper, a1 Anti trypsin, Anti mitochondria, ANA, and Anti SM, were all normal. Anti LKM was border line. Abdominal US with Doppler confirmed normal portal venous system. A Chest CT scan and Abdominal MRI Figure 3,4,5 revealed a thrombosed SVC with venous drainage into the heart through the IVC, azygous and hemiazygous veins and through the multiple collateral vessels in the anterior and posterior wall of chest and abdomen bilaterally. Liver and Portal network was normal. The retained diagnosis was Downhill Esophageal Varices, secondary to thrombosis of the Superior Vena Cava.

Figure 1 Esophagoscopy of the presented case showing a variceal vein situated at the upper third of the esophagus.

Figure 2 Esophagoscopy of the presented case showing esophageal veins at the middle third of the esophagus.

Figure 3 Prominent Azygos vein.

Figure 4 Chest and Abdominal wall collaterals.

Etiologies of “Downhill” esophageal varices

Thrombosis of the Superior Vena Cava or its tributaries is the most common etiology of “Downhill” esophageal varices. There is a long list of etiologies described in the literature including central venous catheterization,2,6,7 mediastinal fibrosis,8–14 primary and metastatic mediastinal tumors,3,10,11,15–19 mediastinal lymphadenopathy secondary to head and neck cancers such as carcinoma of the tongue,20 substernal goiters and thyroid masses,21–23 thyroid carcinoma,3,21–25 lung cancer,3,10,16,18–20,26,27,28 thymoma,3,29 systemic venulitis,30 Behcet’s disease,31–36 Castleman’s disease (angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia),4 and as a late complication after correction of congenital heart defect.37 Downhill varices may also develop without superior vena cava thrombosis,4,38 as seen in goiter,39–41,43–45,46 history of thyroid surgery,22,40–42 severe pulmonary hypertension,47 thyroid tumors,22 abnormal cricopharyngeal muscle constriction or any abnormal muscular constriction of the hypopharyngeal veins.48

Clinical picture of SVC syndrome

Clinical presentation of “Downhill” esophageal varices is dominated by clinical symptoms of Superior vena cava obstruction that were present in 91.4% of the cases described in the literature.3 Patients may present with Face, neck, and arm swelling, tongue swelling, hoarseness, epistaxis, dyspnea, cough, headache, visual disturbance, syncope, dysphagia, upper gastro-intestinal bleeding, haemoptysis, and dilated chest collaterals. Accidentally discovered “Downhill” esophageal varices and upper gastrointestinal bleeding may be the first presentation.31

Incidence

Downhill varices are less common than the so called uphill distal esophageal varices caused by portal hypertension.49,3,50,8,21,10,51,23,52 We found little information about the incidence of downhill varices in the literature. In patients with thyroid disease, Downhill varices were found in 4% of patients with primary goiters, 12% of patients after thyroidectomy, and 54% of patients with recurrent thyroid tumors.22 Similar results were found in a series of 1051 patients with cervical and retrosternal goiter, where 3% of patients developed non-bleeding downhill varices.46

Mechanism of variceal formation

“Downhill” esophageal varices develop when there is an increase in blood flow in the esophageal plexuses.

Case of superior vena cava obstruction. Esophageal varices serve as collateral branches to bypass an obstruction in the superior vena cava, either via azygos vein if the obstruction is located above the level of the azygos vein (proximal), or via the portal system if the obstruction is involving the azygos vein.6,40,8,53,21,10,51,23,52,11,12,14 The most important factors that determine the extension of “Downhill” esophageal varices are the level of Superior Vena Cavaobstruction and its duration.3,8 Obstruction of the Superior Vena Cava above the level of the azygos vein will result in the formation of varices in the upper third of the esophagus. In contrast, obstruction of the Superior Vena Cava below the level of the azygos vein will result in the formation of varices along the entire length of the esophagus.

Case without superior vena cava obstruction

Increase in blood flow in the esophageal plexuses may occur without superior vena cava obstruction. Examples include

- Castleman’s disease4

- Thyroid diseases

In thyroid, blood from the thyroid plexus normally flows through the inferior thyroid veins into the brachiocephalic vein to reach the superior vena cava. In case of obstruction of the inferior thyroid veins, blood flows into esophageal venous plexus (via the deep esophageal veins) leading to “Downhill” esophageal varices. Inferior thyroid veins can be occluded by different mechanisms, such as accidental surgical ligation during thyroidectomy, fibrogenesis secondary to surgery,40,22 or by primary or recurrent thyroid tumors,22 leading to development of proximal esophageal varices.

- Primary esophageal motor disorders "Nutcracker”esophagus and diffuse esophageal spasm were considered as a possible causes of proximal "downhill" varices esophageal.53,54

- Unknown causes: three patients with downhill varices of unknown cause have been reported, probably as a consequence of obstruction of the posterior hypopharyngeal venous plexus by abnormal cricopharyngeus muscle contractions.48

Complications of “downhill” esophageal varices

“Downhill” esophageal varices that are presenting with bleeding are extremely rare in the literature.21,30,51,18,12,14,48 It was reported that 7 to 9 % of patients with “Downhill” esophageal varices presented with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage,5,3,30 with some cases of life-threatening bleeding.6,30 Most of the bleeding varices are caused by vena cava obstruction due to tumors or mediastinal fibrosis.21,51,18,12,14 “Downhill” varices represent only 0.1% of all esophageal variceal bleeding.55 Two explanations were suggested: the first is the lack of coagulopathy usually associated with chronic liver disease in varices secondary to portal hypertension, and the second is the higher location of “Downhill” varices in the esophagus, away from erosive gastroesophageal reflux. “Downhill” varices are located in the submucosa of the proximal esophagus, in contrast to the esophageal varices of portal hypertension that are located in the superficial subepithelium of the distal esophagus.49,40

Treatment

Treatment plan needs to be individualized. Primary treatment of “downhill” esophageal varices is directed toward the etiology.49 In superior vena cava thrombosis, removal of a catheter, chemical or mechanical thrombolysis of the clot [56] and/or venoplasty and stenting2,57,58 has been reported to resolve the problem. In surgical candidates a vascular bypass of the superior vena cava can be attempted.6 Treatment of the underlying medical condition was sufficient in some cases to resolve the varices, such as steroids and dapsone in systemic vasculitis,30 chemoradiotherapy or resection of a tumor,4,26,15,59,60 thyroidectomy41,43,21,45 and radioactive iodine therapy40 in case of goiter, and surgical resection for Castleman's disease.4 Inferior thyroid artery embolization was attempted in a case of downhill varices caused by a goiter.39 Sclerotherapy was complicated by spinal cord infarction in some cases,48,61,62 caused by flow of sclerosant from the azygos to spinal veins when injected at the level of the middle and upper esophagus.61 Complication with pulmonary embolism was also described.63

Variceal band ligation is effective for controlling bleeding in patients with uncorrectable underlying disorders.49,31,64 The site of banding was not clearly defined. Some suggest banding proximal to the varices for hemodynamic reasons, as opposed to the distal banding in esophageal varices due to portal hypertension.67 The risk of bleeding or perforation seems higher because of the weakness of the proximal esophageal posterior wall and overall lack of serosa.65,66 Endoscopic treatment of “downhill” varices should be undertaken only in severe cases.46 The use of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube can be lifesaving in case of uncontrolled bleeding.40 When all the above measures fail, palliative measures may be applied.6,46 Possible technical complications of the treatment are not well studied because of the rarity of this condition.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Chandra A, Tso R, Cynamon J, et al. Massive Upper GI Bleeding in a Long-term Hemodialysis Patient. Chest. 2005;128(3):1868–1873.

- Greenwell MW, Basye SL, Dhawan SS, et al. Dialysis catheter-induced superior vena cava syndrome and downhill oesophageal varices. Clin Nephrol. 2007;67(5):325–330.

- Papazian A, Capron JP, Rémond A, et al. Upper esophageal varices: a study of 6 cases and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1983;7(11):903–910.

- Serin E, Ozer B, Gumurdulu Y, et al. A case of Castleman's disease with "downhill" varices in the absence of superior vena cava obstruction. Endoscopy. 2002;34(2):160–162.

- Felson B, Lessure AP. “Downhill” varices of the esophagus. Dis Chest. 1964;46:740–746.

- Pop A, Cutler AF. Bleeding downhill esophageal varices: a complication of upper extremity hemodialysis access. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(3):299–303.

- Hussein FA, Mawla N, Befeler AS, et al. Formation of downhill esophageal varices as a rare but serious complication of hemodialysis access: a case report and comprehensive literature review. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2008;12(5):407–415.

- Rosenblatt ML, Rabinowitz M. Downhill esophageal varices (EV) secondary to fibrosing mediastinitis (FM) AJG 95: 2602-2603. 2000.

- Basaranoglu M, Ozdemir S, Celik AF, et al. A case of fibrosing mediastinitis with obstruction of superior vena cava and "downhill" esophageal varices: a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;28(3):268–270.

- Otto DL, Kurtzman RS. Esophageal varices in superior vena cava obstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 1964;92:1000–1012.

- Sheiner NM, Palayew MJ. "Downhill" esophageal varices in superior vena caval obstruction. Can Med Assoc J. 19649;100(20):961–964.

- Snodgrass RW, Mellinkoff SM. Bleeding varices in the upper esophagus due to obstruction of the superior vena cava. Gastroenterology. 1961;41:505–508.

- Anderson IF, Dannheimer I. A case of "downhill varices". S Afr Med J. 1970;44(36):1035–1037.

- Pugliese FM. A surgical approach to bleeding downhill varices. Angiology. 1973;24(10):606–611.

- Shirakusa T, Iwasaki A, Okazaki M. "Downhill" esophageal varices caused by benign giant lymphoma. Case report and review of "downhill" varices cases in Japan. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;22(2):135–138.

- Weinberg T. Observations on occurrence of varices of esophagus in routine autopsy material. Am J Clin Pathol. 1949;19(6):554–557.

- Garrett NJ, Gall EA. Esophageal varices without hepatic cirrhosis. AMA Arch Pathol. 1953;55(3):196–202.

- Mikkelsen WJ. Varices of the upper esophagus in superior vena caval obstruction. Radiology. 1963;81:945–948.

- Subramaniam R, Madanagopalan N, Krishnan KT, et al. A case of anaplastic bronchogenic carcinoma with "downhill" varices of the esophagus. Dis Chest. 1967;51(5):545–549.

- Kokubo M, Sasaki H, Sakai S, et al. "Downhill" esophageal varices due to superior vena cava syndrome]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;29(7):854–857.

- Johnson LS, Kinnear DG, Brown RA, et al. "Downhill" esophageal varices. A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Surg. 1978;113(12):1463–1464.

- Lagemann K. Upper oesophageal varices due to thyroid enlargement. Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed. 1973;118(4):440–445.

- Sorokin JJ, Levine SM, Moss EG, et al. Downhill varices: report of a case 29 years after resection of a substernal thyroid gland. Gastroenterology. 1977;73(2):345–348.

- Van Beusekom HJ, Beex LV, Smals AG, et al. Downhill esophageal varices in thyroid carcinoma. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1978;122(2):38–41.

- Ignjatović M, Cerović S, Stanić V, et al. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid in intrathoracic goiter. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2003;50(3):85–91.

- Tanaka H, Nakahara K, Goto K. [Two cases of "downhill" esophageal varices associated with superior vena cava syndrome due to lung cancer]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;29(11):1484–1488.

- Woodring JH. Unusual radiographic manifestations of lung cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 1991;28(3):599–618.

- Ishikawa M, Kozasa K, Munechika H, et al. [A case of downhill esophageal varices with bronchogenic carcinoma]. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1987;32(10):1153–1156.

- Bos GM, Saleh A, Schouten HC, et al. "Downhill" oesophagus varices: a clue to a serious disease. Neth J Med. 1992;40(1–2):27–30.

- Maton PN, Allison DJ, Chadwick VS. Downhill esophageal varices and occlusion of superior and inferior vena cavas due to a systemic venulitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7(4):331–337.

- Tavakkoli H, Asadi M, Haghighi M, et al. Therapeutic approach to downhill esophageal varices bleeding due to superior vena cava syndrome in Behcet's disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:43.

- Orikasa H, Ejiri Y, Suzuki S, et al. A case of Behcet's disease with occlusion of both caval veins and downhill esophageal varices. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(4):506–510.

- Ichikawa M, Kobayashi H, Mukai M, et al. [Superior vena cava syndrome as initial symptom of Vasculo-Behcet's disease-case report]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;29(10):1344–1348.

- Tsuji S, Suzuki Y, Tomii M, et al. [Behcet's disease associated with multiple cerebral aneurysms and "downhill" esophageal varices caused by superior vena cava obstruction: a case report]. Ryumachi. 1990;30(5):375–381.

- Ishikawa R, Noguchi T, Matsumoto K. [A case of downhill esophageal varices-Behcet disease associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm and occlusions of the superior and inferior vena cava]. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1986;87(12):1576–1582.

- Suzuki H, Mizuguchi A, Fujii M, et al. A case of vasculo-Behçet with esophageal downhill varices (author's transl). Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1982;79(1):93–96.

- Miller LT, Lang P, Liberthson R, et al. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage as a late complication of congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23(4):452–456.

- Savoy AD, Wolfsen HC, Paz-Fumagalli R, et al. Endoscopic therapy for bleeding proximal esophageal varices: a case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(2):310–313.

- Ibis M, Ucar E, Ertugrul I, et al. Inferior thyroid artery embolization for downhill varices caused by a goiter. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(3):543–545.

- Fleig WE, Stange EF, Ditschuneit H. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from downhill esophageal varices. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27(1):23–27.

- Kelly TR, Mayors DJ, Boutsicaris PS. Downhill varices; a cause of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am Surg. 1982;48(1):35–38.

- Smallridge RC. Metabolic and anatomic thyroid emergencies: a review. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(2):276–291.

- Bedard EL, Deslauriers J. Bleeding "downhill" varices: a rare complication of intrathoracic goiter. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(1):358–360.

- Anders HJ. Compression syndromes caused by substernal goitres. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74(872):327–329.

- Van der Veldt AA, Hadithi M, Paul MA, et al. An unusual cause of hematemesis: Goiter. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(33):5412–5415.

- Schmidt KJ, Lindner H, Bungartz A, et al. Mechanical and functional complications in endemic struma. MMW Munch Med Wochenschr. 1976;118(1):7–12.

- Areia M, Romãozinho JM, Ferreira M, et al. Downhill varices. A rare cause of esophageal hemorrhage. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2006;98(5):359–361.

- Palmer ED. Primary varices of the cervical esophagus as a source of massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Dig Dis. 1952;19(12):375–377.

- Vorlop E, Zaidman J, Moss SF. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Downhill esophageal varices secondary to superior vena cava occlusion. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(6):1863–2158.

- Calderwood AH, Mishkin DS. Downhill esophageal varices caused by catheter-related thrombosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(1):e1.

- Martorell F. Esophageal varices due to superior caval hypertension. Angiologia. 1955;7(2):49–53.

- Hirose J, Takashima T, Suzuki M, et al. "Downhill" esophageal varices demonstrated by dynamic computed tomography. J Compute Assist Tomogr. 1984;8(5):1007–1009.

- Pashankar D, Jamieson DH, Israel DM. Downhill esophageal varices. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29(3):360–362.

- Micklefield GH, Schwegler U, Hüppe D, et al. Circumscribed venous ectasia of the upper esophagus and downhill varices in primary disorders of esophageal motility. Z Gastroenterol. 1991;29(7):346–348.

- Areia M, Romãozinho JM, Ferreira M. Unidadede CuidadosIntensivos de Gastrenterologia – 13 anos de vida. GE-J Port Gastrenterol. 2005;12(3)(Supl.):62.

- Rose SC, Kinney TB, Bundens WP, et al. Importance of Doppler analysis of transmitted atrial waveforms prior to placement of central venous access catheter. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1998;9(6):927–934.

- Carcao MD, Connolly BL, Chait P, et al. Central venous catheter-related thrombosis presenting as superior vena cava syndrome in a haemophilic patient with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2003;9(5):578–583.

- Hennequin LM, Fade O, Fays JG, et al. Superiorvena cava stent placement: results with the Wallstent endoprosthesis. Radiology. 1995;196(2):353–361.

- Armstrong BA, Perez CA, Simpson JR, et al. Role of irradiation in the management of superior vena cava syndrome. Int J Radiate Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13(4):531–539.

- Pérez-Soler R, McLaughlin P, Velasquez WS, et al. Clinical features and results of management of superior vena cava syndrome secondary to lymphoma. J Clin Onco. 1984;2(4):260–266.

- Heller SK, Meyer JR, Russell EJ. Spinal cord venous infarction following endoscopic sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. Neurology. 1996;47(4):1081–1085.

- Seidman E, Weber AM, Morin CL, et al. Spinal cord paralysis following sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1984;4(5):950–954.

- Tsokos M, Bartel A, Schoel R, et al. Fatal pulmonary embolism after endoscopic embolization of downhill esophageal varix. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123(22):691–695.

- Palmer ED. The sources of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Nebr State Med J. 1967;52(11):490.

- Conklin JL, Christensen J. Motor function of the pharynx and esophagus. In: Johnson LR et al., editors. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Raven Press, New York, USA. 1994.

- Boyce GA, Boyce HW. Esophagus: anatomy and structural anomalies. In: Yamaria T et al., editoros. Textbook of gastroenterology. Lippincott, Philadelphia, USA. 1995.

- Dhawan SS. Downhill varices-banding proximal to varix? Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(1):359–360.

©2015 Jammal. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the,

which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.