eISSN: 2577-8250

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 1

1University of Zanjan, Iran

2Farhangian University of Tabriz (Allameh Amini Campus), Iran

Correspondence: Shaham Asadi, Master of Architecture, Teacher of Architectural Drawing, Education, University of Zanjan, East Azarbaijan Province, Iran

Received: January 06, 2023 | Published: January 25, 2023

Citation: Asadi S, Sodagar B. Kanaqah, Silent Irfan. Art Human Open Acc J. 2023;5(1):11-21. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2023.05.00182

Architecture has always been associated in some way with a fundamental thought. It seems that the collection of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili, as one of the important centers of mysticism and Sufism, has also been influenced by mystical ideas and concepts, and these concepts have been effective in shaping the architecture of this collection. Sheikh Safi al-Din's collection was built during different periods, but historical texts state that Sadr al-Din Musa - the son and successor of Sheikh Safi - designed the order and structure of the tomb himself and through a dream or imagination inspired its structure to the architects of this building (Ḵānaqāh).1

Therefore, it may be possible to recognize the architectural connection of this collection with mystical thought and concepts. In the course of mysticism, the seven stages are mentioned, through which the seeker reaches the stage of annihilation in the sight of God. This article tries to explore its connection with the formation of Sheikh Safi al-Din collection by knowing exactly the characteristics of each of these stages. To reach the question of the present article, first the thought of "Tariqat" is studied and then the collection of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili is introduced. In the next step, the relationship between these two areas will be examined based on the available evidence and documentation (Silent Irfan).2

Keywords: Sheikh safi al-din ardabili, mysticism, Kānaqāh, the seven levels of mysticism in the body of architecture

1In Persian ḵānaqāh, literally a ‘dwelling place,’ or a ‘place of residence,’ refers to an Islamic institution and physical establishment, principally reserved for Sufi dervishes to meet, reside, study, and assemble and pray together as a group in the presence of a Sufi master (Arabic, šayḵ, Persian, pir), who is teacher, educator, and leader of the group.

2In Islam, ‘Irfan (Arabic/Persian/Urdu: عرفان; Turkish: İrfan), literally ‘knowledge, awareness, wisdom’, is gnosis. Islamic mysticism can be considered as a vast range that engulfs theoretical and practical and conventional mysticism and has been intertwined with Sufism and in some cases they are assumed identical. However, Islamic mysticism is assumed as one of the Islamic sciences alongside theology and philosophy.

The Irfan of the method of wisdom, according to many people of argument, depends on enthusiasm and taste in the beloved rather than rational reasoning. From the first days of the formation of "Mysticism Tariqa3" in Islamic society, due to the social and individual behavior of this tribe (pioneers and followers of Sufism), they have been referred to as "Ahlullah", "Ahl Tasawwu4f" and "Motasawwfe". Different and sometimes conflicting views have been presented about Sufism and Islamic mysticism and the origin of it, which makes it difficult or even impossible to draw a precise and official limit in this case. Some consider it a non-Islamic phenomenon, the legacy of Neo-Platonism philosophy, which was transmitted from the Christian world to the Islamic community by Syrian monks. Some consider the origins of Sufism to be the teachings of the Zoroastrian and Manichaean religions, which have been propagated by Muslimized Zoroastrians in the Islamic community. It is also considered the reaction of Iranian-Aryan thought to Arabic thought-Semitic. "Some consider Islamic Sufism to be influenced by Buddhism, Hindu mysticism, and asceticism and practical austerity that has infiltrated Islamic society through the Iranians. Among the many definitions of mysticism and Sufism, what has been emphasized as the true manifestation of the spirit of Sufism is its reliance on the elements of asceticism, poverty, purification, self-cultivation, and stepping on material and physical possessions to connect to the source of knowledge.

"It's not more than two steps all this way / the road approached and a short speech.

Take a step towards existence / "And you take that next step in the love of God." (Sanai)

In this regard, in the early periods of Sufism, Sufi circles centered on prominent shaykhs gradually established the first ḵānaqāhs (on the one hand, seclusion to stay away from the world, and on the other hand, raising the banner of opposing the caliphs' palace and staying in the mosque of Shariat) as They formed the largest and most extensive Sufi social institution. After the establishment of Sufism, the ḵānaqāh became the main gathering place of elders and shaykhs Sufis in Islamic-Iranian Irfan, and as a result, the Murid5 were trained, and the ḵānaqāhs played an important role in the upbringing, training and development of the Murids. The purpose of this article is to introduce the mystical silent symbols in the monastic contexts and how the mystical elements are reflected in the geometric shapes used in the body of the ḵānaqāhs (in the case of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili ḵānaqāh) in a descriptive-analytical manner.

3A Tariqa (or tariqah; Arabic: طريقة ṭarīqah) is a school or order of Sufism, or specifically a concept for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking haqiqa, which translates as "ultimate truth". A tariqa has a murshid (guide) who plays the role of leader or spiritual director. The members or followers of a tariqa are known as muridin (singular murid), meaning "desirous", viz. "desiring the knowledge of God and loving God" (also called a faqir).

4Sufism

5In Sufism, a Murīd (Arabic مُرِيد 'one who seeks') is a novice committed to spiritual enlightenment by sulūk (traversing a path) under a spiritual guide, who may take the title murshid, pir or shaykh. A sālik or Sufi follower only becomes a murīd when he makes a pledge (bayʿah) to a murshid. The equivalent Persian term is shāgird

The word Sufi literally means "woolen" and by extension "Wearing wool". Undoubtedly, in the pre-Islamic period, woolen clothing was associated with spirituality.1 Lings attributes wool to Moses and considers Sufism to be one of the most important and original aspects of Islamic culture and civilization. A Sufi purifies the soul by turning away from carnal and worldly desires through inner spiritual journey. Along with Sufism, mysticism, and the life of the great Sufis, familiarity with monastic centers and the history of its developments is very useful and important.2 The first Sufi ḵānaqāhs was established in a place called "Ramla Sham" or somewhere in the "Ibbadan" and around the year one hundred and fifty AH. Formation of a ḵānaqāh officially in Iran by Abu Saeed Abolkhair 440 AH. It originated in Khorasan and the city of Neishabour in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Sufism is very important in the Ilkhanate period. The peak of the popularity and prosperity of Sufism and the construction of ḵānaqāhs in this period. But at the same time, in this period, Sufism became vulgar.2 The eighth century can be considered the peak of ḵānaqāh construction, as there were close relations between Shiites and Sunnis.

John Spencer Terry Ingham presents a plan to explain the social developments of the Sufis and the formation of Sufi communities, which consists of three parts:

Considering the subject of this article, which is to study the causes of the emergence of the early Sufi communities, here we refer only to the first stage, i.e the stage of monastic Sufism.

Do not travel next to your lover Darwish / that is enough spiritual journey and the corner of monasteries" (Hafez)

The ḵānaqāhs is a house and is composed of “Khaneh” and "Gah" (Dehkhoda under the ḵānaqāh) and has been used to refer to the residence and community of Sufis. The word "Khan" is next to "Khanak" and in the Old Persian "Ahaneh", which is considered to be derived from the Avestan source "Kan" and in Arabic it was "Khaneh". Of course, for a long time in different regions and at different times, there have been other words to refer to the house of Zahedan and Sufis; Including " ribat", "tekije ", " Zawiyya ", "Tomb", "Langar", "Madrasa"," ḵānaqāh" and "Dovayreh".The word ḵānaqāh itself has been recorded in several forms in various old works and books; Such as "Khaneh Gah", "Khanjah", "Khangah", "Khangeh", "Khorangeh", "Khordgeh", "Khornqah", "Al-Kharnakah", "Khangeh".3–5 Dr. Mohammad Reza Adli in his article "Causes of the expansion of early Sufi communities and the formation of ḵānaqāhs "provides various interpretations of history and documents about the meanings of the word ḵānaqāh: For example, Yaqut Hamavi and Samani and the anonymous author of "Hudud al-Alam6" interpret the word ḵānaqāh as follows: The first part of this word, "Khan", from the word Khaneh means place of residence and Gah the suffix of place.6–8 Khan in the Persian word is used in multiple meanings:

Khanagah is the name of a town in Kharazm and a neighborhood in Tehran. Also, a Khanagah means the world, the “Majles Gah” and the home, that is, the amount of land on which a house can be built, its purpose has been used as a special house, and it has been ruled as science, and it can be more against the khan.3 In later sources, Khan has been considered to be derived from Khawn meaning tablecloth or from the act of reciting. Therefore, it is not correct in terms of etymology and derivation; because in Persian writing and Arabic phonology, the omission of "w" in the word reader has no precedent; as the word Persian reader in Arabic is recorded as reader.9 The word “Khawn " in Persian means:

Maghrizi also considers Khan to mean eating the sultan and Khaneghah to Khanak, which is the plural of Khankah in Persian, which originally considers it to be Khonqah, which is the meaning of Khankah. The word khanak was found in Islam around the fourth century and has been called the place of worship and solitude of Sufis.4,10

6In English, the title is also translated as "The Regions of the World" following Vladimir Minorsky's 1937 translation,

Many scholars have long traced the lineage of the Sufis to the "Ahl al-Safa": a group of immigrants with the Prophet (pbuh) who left their wives in Mecca and lived in poverty in Medina. He lived and served with asceticism and contentment in "Safa" or a platform near the Prophet's Mosque and was close to the Prophet in the Greater and Lesser Jihad.11–13 If the "people of Safa" are the ancestors of the Sufis, "Safa" itself is the ancestor of the ḵānaqāh.14

The first official and planned ḵānaqāh has been attributed to Abu Saeed Abu al-Khair.15 The formation of the ḵānaqāh was officially established in Iran by Abu Sa'id Abi al-Khair 440 AH in Khorasan and the city of Neishabour in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Although there were places before him called Khaneghah or Dovayreh, ḵānaqāh was officially established by him in Iran with specific and codified plans.2 Apparently, the word ḵānaqāh was first mentioned in the works of writers and in the column of Manichaean and Karamian works of the fourth century and increased in the fifth century AH with the expansion of Sufi communities and monasteries.5,14 The anonymous author Hudud al-Alam (written in 372 AH) refers to the Manichaean house: "Samarkand is a large and prosperous city and inside it is the Manichaean house and they are called Naghushak (drinkers)".6

The Manichaean ḵānaqāh was stretched from Babylon to Sogdia, which can even be seen in Ibn Nadim's report in the list, and this can be considered as evidence of the presence of the Manichaeans in Samarkand. The Khorasan region was important in terms of mysticism and Sufism, because some of the true founders of the Islamic Sufism school came from there and Khorasan's share in Sufism was more than other Islamic regions, even some of the great Sufis of Baghdad and other centers were born and They were the product of the land of Khorasan.4 Moghaddasi considers the Karamians in Khorasan, Jorjan, Transoxiana, Tabarestan and in the west to Jerusalem.16 Until the middle of the fifth century, Moghaddasi considered the Sufis to be separate from the monasteries and even described the places of Sufism as a place separate from the ḵānaqāhs: I ate Porridge7 With the Sufis and ate Tarid8 with the Khanaqis and halva9 with the shipwrights ”.16 In the Ilkhanid period, we see the increase of ḵānaqāhs and their remarkable growth, so that there is important evidence from this period that indicates the vastness of Sufism and the number of Sufis in the Ilkhanid realm, which shows the special support of the rulers of the time for ḵānaqāhs and Sufis.

The eighth century is a period of closeness between Shiism and Sufism and their further fusion and the spread of Shiism in Iranian society. The prevalence of Shiism causes that Sufi dynasty that have a Sunni status in the beginning, such as "Safi al-Din Ardabili" dynasty, gradually approach Shiism and establish the Shiite government of Iran in later periods. The Safavids were Sufis who, after gaining power and concentrating on it, tore their woolen clothes and instead wore the clothes of war and the caliphate, and instead of ḵānaqāhs, established the centers of government and converted Sufi Shi'ism to jurisprudential Shi'ism. There are several reasons for the prevalence of ḵānaqāhs construction in the Ilkhanid period, which we will briefly discuss below:

7Porridge (historically also spelled porage, porrige, or parritch) is a food commonly eaten as a breakfast cereal dish, made by boiling ground, crushed or chopped starchy plants—typically grain—in water or milk. In Persian harissa

8Tarid is a type of grilled food and is also known as Arabic lasagna. This dish includes vegetables such as carrots, beans, onions, potatoes cooked with chicken or mutton with tomato sauce and spicy spices. Tarid is often served with bread. The bread is soaked in the stew of this dish and wrapped in it.

9Halva (also halvah, halwa and other spellings) refers to various local conformance recipes in west asia and its vicinity. The name is used for referring to a huge variety of confections, with the most geographically common variety based on fried semolina. (Wikipedia)

Sufi life had rites and requirements that could not be fulfilled in the mosque; Needs such as solitude, companionship with dervishes, service of dervishes and following the Peers10, and basically a religious system that was not compatible with the religious system of the jurists who usually ruled the affairs of mosques.14 Edward Joseph writes in the definition of a ḵānaqāh: "A ḵānaqāh is a place where Sufis gather and practice Sufi customs and traditions, and their needy dervishes take refuge in it".19 Ibn Khafif in his book Al-Iqtisad warns his seekers and Muslims in the first place from associating with "Ibn al-Dunya11" and political rulers, Ibn Khafif says: "Seekers should wear simple clothes, avoid eating meat. Be sleepy and undernourished and practice sincerity and sincerity.20 Ibn Khafif in his book "Al-Iqtisad" warns his seekers in the first stage of associating with "Ibn al-Dunya" and political rulers, Ibn Khafif says: "Seekers should wear simple clothes, avoid eating meat. Be sleep deprived and have little food and practice sincerity and sincerity.20

"A Sufi must take his heart out of this world and sit in solitude and raise his eyes and procrastinate his senses and accompany his heart with the knowledge of the kingdom and avoid worldliness". The Murids disciple turned his back on the ordinary life and joined the monastic life. In this way of life, he had responsibilities; From obedience to shrewdness in understanding the advice of the Peer, honesty, commitment, confidentiality, sacrifice, light style, keeping the Peer's honor, serving the old man and other disciples, and accompanying the community.13,21 In the ninth century, many ḵānaqāhs were destroyed for political reasons, and a number of them were renamed. For example, the "Rosht-e-Khwar" building, which had changed its use throughout history due to these pressures, and many scholars, considered it a mosque-tomb. But in the article "Rasht Eater Building, Mosque or ḵānaqāh" by Dr. Bidhandi, it is proved that this building is a ḵānaqāh. Therefore, familiarity with the functional and physical hierarchy of the building for the structure is one of the priorities that must be addressed, because only then can the effects of Sufi thought be found in the ḵānaqāh. In terms of physical hierarchy, the ḵānaqāh space is open, semi-open and closed; the open space is the courtyard of the ḵānaqāh and the semi-open space is the porch (Sefeh), it includes the closed space of the dome and the rooms, which is a space for Chilla12 and leaving the world. And in terms of functional hierarchy, it is public, semi-public and private. The public arena is a place where everyone except the people of the ḵānaqāh is allowed to be present, and that is the courtyard of the ḵānaqāh. The semi-public space is where the people of the ḵānaqāh are, but those who enter the ḵānaqāh also see them. It is the plateau or porch that is the place where the sheikh or the guide speaks. Private space is only the place of the residents of the ḵānaqāh, whether for remembrance or for residence, education, seclusion in the rooms and According to Imam Mohammad Ghazali, "let the heart come out of this world".22 (Diagram 1)

10Elders

11The children of the world are human beings who consider themselves the children of the world and always work for worldly life. In their imagination, the world is like their father, and their desire, will and love are for the world. Secularists.

12Chilla (Persian: چله, Arabic: أربعين, both literally "forty") is a spiritual practice of penance and solitude in Sufism known mostly in Indian and Persian traditions.

Dedicating the ḵānaqāh to the Sufi gathering place is an official practice that existed in the time of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) as a Sufa13 that was the residence of the poor and the companions. In his article "ḵānaqāh", Mohammad Hussein Tasbihi quotes the benefits of establishing a ḵānaqāh from the words of Izz al-Din Mahmud ibn Ali Kashani, who considers it the best commentary on the ḵānaqāh:

13"Sufa" was a platform where the poor and homeless lived.

Ḵānaqāh is a place for dervishes to gather and perform Sufi acts and programs.4 The discussion of "Ribat” is of particular importance because it is the origin of the ḵānaqāh. Before the emergence of ḵānaqāh, it was the central border Ribat of Sufis and seekers and performed monastic acts.24 ḵānaqāh is the center where eligible people can learn the teachings of the highest form of knowledge. After the Mongol invasion, the ḵānaqāh became the center of other aspects of traditional Islamic education and many rational and religious sciences were taught there.25

So ḵānaqāh was a place for education, austerity, providing food and shelter, teaching Islamic sciences, writing and publishing books, and creating a library of socio-cultural activities that took place in ḵānaqāh. It was a place for the mystics and ascetics of the Sufis, which began with solitary asceticism and individual asceticism, which gradually became isolated for various reasons and separated from society and gradually gathered around the early Sufi elders. In fact, the elders were the connecting point and the attraction, connecting all the members of these congregations. He mentioned the circle of Junaid's companions in Baghdad and the students of "Testari" in Basra. In Iran, groups of Sufis were also being formed in the eastern lands of the Islamic realm; for example, in Shiraz, where the number of Ibn Khafif's followers is said to have reached thousands.26 For this reason, a field was created to expand the rituals and ceremonies of ḵānaqāh, and it had different parts, the most important of which are:

A place for travelers, rooms for the inhabitants, halls for group activities such as spiritual dancing, prayer and supplication, a place for preaching, a special place for ḵānaqāh guide, a place for feeding, a center for teaching books, a library, a building for the kitchen and a food warehouse Existence of a bath for the use of residents and travelers, stables for travelers' livestock, a place for nursing patients, lands and gardens around it for agricultural affairs, as well as other related buildings that need to be present.4 Jonathan Bloom, in an article entitled “ḵhānaqāh" in the Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, wrote, "Unlike the school, he considers the ḵānaqāh to have no significant plan".27

In the past, it was a temporary and public house for those who did not have shelter. Mystics called it a building where they gathered and had training and lessons or formed a circle and held a meeting of ecstasy. They also had large houses within a four wall called “Hazira”. Some mystics had a special place for themselves, where they gathered their disciples and called it "Langar ". Langar means home, Examples are the Mahan Langar in Kerman and the Jam Langar in Mashhad.28 Below are the places and buildings that were used as monasteries.

Mosque

The first building built in Islam is a mosque. In addition to the function of praying, mosques were also among the educational buildings. The issue of using mosques for education continued until the fourth and fifth centuries AH, when schools entered the education scene independently during the reign of Khajeh Nizam al-Mulk. In the meantime, various groups, including Sufis, gathered in mosques around each other, because in the early centuries of Islam, there were no official centers such as monasteries for the Sufis, and another was the proper position of mosques for propaganda, which attracted a group of monks to mosques. "As Junaid in 298 AH was engaged in guiding the people in the Grand Mosque and Husari in 371 AH in the courtyard of Mansour in Baghdad spoke about monotheism".

Mountaineering and cave-dwelling and the cult of "Shekftieh"

Caves have long been considered a natural refuge for human habitation and are considered archetypes in literature. Jung says about the secret of the cave: "Cave means a person communicates with the contents of his subconscious mind by penetrating the subconscious mind".29,30 In mystical literature, the mountain next to the cave is a place that causes the souls of the prophets to rise and fall, and for this reason, the Sufis used nature to seek solitude and cultivate their souls in order to help strengthen their souls.

The history of human cave-dwelling lies in the distant past, as we read in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh about ancient religion: "Jamshid tells his clerics (Katozian group) to go to the mountains and worship there". Those who were isolated in the caves gradually established a sect for them and called it the "Blossoming Sect". The word "Shekoft" which means crypt and cave in Persian and in the book "Awarf Al-Ma'aref" by Sheikh Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi has also confirmed the existence of such people. It is also said about the Zoroastrian clerics that: "Moghans climbed on top of a mountain that had a kind of stone and was adorned with springs and rare trees and washed themselves and then worshiped God for three days".31 This issue of the spirituality of the mountain and the God-seeking of the prophets in the cave mountain attracted Islamic Sufis as well. It is as if people like Ibn Taymiyyah do not accept mysticism and seclusion in the mountains, arguing that the Prophet's solitude in the Hara Cave was before his mission and he did not do so during his mission.

Ribat

This word has been used in Dehkhoda dictionary in different meanings such as border Checkpoint, Caravanserai, ḵānaqāh, Navakhaneh14, Gharibkhaneh15, guest house, castle, temple, and temple has been used in virtual meanings.32 The root Ribat is used in Arabic to mean "gathering horses for battle"; or it is a place where they keep no more than five horses and it also means the border to join the enemy.5,10,33 Perhaps the Sufis of Baghdad preferred the word Ribat to the Persian word Khaneghah, or they saw its implicit reference to jihad as more in line with their ideal, the Great Jihad.9

At the end of the fourth century AH, this word refers to a kind of fortress that was used as a basis for the continuity of the world. The term was also used to describe urban structures that had commercial purposes or where Sufis gathered.33 Sometimes monasteries were built outside the city, which was a very cozy, comfortable and relaxing place, and these monasteries were called Ribat. The Ribats "had a room called the" Zāwiyah" which was a secluded and cozy corner where mystics and ascetics worshiped and roamed free from the evils of the world. The Ribats were sometimes very far away. In the first centuries of Islam, with the advent of Sufism in Iran, mystics brought together individuals and groups who were in a simple position. Gradually, the ḵānaqāh became one of the valuable and sacred buildings where people took refuge and recited Fateha16 and made pilgrimages.

Ribat has been used for the first time in the book "Surah Al-Arz" by Ibn Hawqal and Ahsan Al-Taqasim Al-Maqdisi. According to these two writers, Ribats was seen in all parts of Khorasan, Transoxiana, and South Caucasus. Ibn Hawqal and Muqaddisi have mentioned the number of Ribats in Bikand (on the border of Bukhara).10,34 The first use of this word is used as a border checkpoint. Kiani believes that in the first centuries of Islam, the world was divided into two parts, Dar al-Islam (Islamic-dominated lands) and Dar al-Harb (and lands outside the control of Islam), and ligaments were established on the border between Dar al-Islam and Dar al-Harb.4 And Abu al-Mafakher Bakhrezi writes in Orad al-Ahbab: "The service of Rabat is several things: cooking and baking bread and washing comprehensive clothes, washing and cleaning the Rabat and cleaning the house of purity.35,36

In these Ribats, some ascetics, such as the people of Sefeh, practiced asceticism and fought in battles, such as Ibrahim Adham. Gradually, with the spread of Islam and its strengthening, these ligaments became special for wool and became centers of worship or study and discussion. In his book "Al-Daras Fi Tarikh Al-Madaras", Naimi mentions one of the Ribats, which was first a military fort and then a caravanserai, and then a meeting place for Sufis). Thus Rabat became a place of Sufi worship in the cities; it is not clear exactly why the Sufis are called monasteries, but what appears is that the ḵānaqāh was first practiced in the Karamyan religion, and from the second half of the fifth century, with the rise of the Sufi sect, the ligaments also increased. Of course, the Sufi ḵhānaqāhs of Baghdad were often called Rabat. In other Islamic lands, the word ḵhānaqāh was more common.

Zāwiyah or corner

Zāwiyah literally means corner and seclusion, and functionally it means ḵānaqāh and also means an independent room in a ḵānaqāh, mosque, or school. Zawiyah in Kharqani's cases means "carpet" and in Asrar al-Tawhid it means "all the contents of the sheikh". Zawiyah of the institution was small and the sheikh was at the head of it, and unlike ḵhānaqāhs and Zawiyahs, there were no endowed places. However, they did not enlist in the post-acceptance period.4,5,37,38 And that the Zāwiyah of an independent room or a secluded corner or a single building with its own function is something that has arisen throughout the history of its formation, and in general the local angle has not been a Sufi seeker except for worship and self-cultivation.

These buildings were built in remote places. Like Khomeini's corner, this was built next to a spring full of beautiful and colorful fish. In the mountains of Yazd, there is a cave where water drips from the sky and collects in rocks. People believe that whatever is taken away from it will not diminish. This was the Zāwiyah of the "Chillakhaneh". A tree grew in this cave that comes out of the mouth following the light and creates a beautiful landscape. The architectural design of the ḵhānaqāh was generally similar to that of Ribat and the Caravanserai, with a central courtyard and a number of rooms around it. Of course, in larger ḵhānaqāhs such as Mahan or Ardabil and Ahar, there was also a meeting hall or dome.28

Dovayreh

Another word used instead of ḵhānaqāh is Dovayreh, which means Sara and small house. The word “Dovayreh" is used in Yaqut Hamavi's book Ma'jam al-Baldan to mean a village around Neishabour and as a neighborhood in Baghdad.8 Dr. Shafiee Kadkani believes that the translation Dovayreh of Khaneghah and Khaneghah is its translation, which means that Dovayreh means Khanak, which later became Khaneqat, Khanateh, and finally Khaneghah. The Dovayreh also means the home of the Sufi sheikh and scholar, such as the Qushairi Dovayreh, the Dovayreh of Abu Sa'id ibn Abu al-Khair, and so on. In a hadith narrated by Jabir Ibn Abdullah Ansari from the words of the Prophet, the word "Ahl al-Dawarat and Dawarat al-Hawla17" is used about the people of the house and its inhabitants.39 And Yaqut Hamavi in the dictionary of the country defines the flower house of the old woman and Anoushirvan Sassanid, the flower house of this old woman as a small circle. The whole Dovayreh has undergone many changes throughout its history, but in the end it had no meaning other than a ḵhānaqāh and a gathering place for Sufis, and gradually ḵhānaqāh programs became common there as well.

Tekije

Tekije on the Arabic word is from the root "waka18" and means to put something behind and rely on, and in Sufism, it refers to a place where dervishes and poor people are fed. The German Kempfer considers Tekije as "a cozy corner and hut that is for resting and socializing with others and its expenses are low and most of its income is obtained through beggars".40 Tekije was used in Turkey during the Ottoman period to mean a ḵhānaqāh, and later found a similar meaning in other lands. Eventually, the word Tekije gradually moved away from the concept of a ḵhānaqāh and a tomb. With the arrival of taziyeh and roza recitation ceremonies, he gave his field of activity to a Shiite religious ceremony. One of the most famous supports is the support of the government.

Qalandar, Langar and Kharabat19:

"Qalandar" was the name of the place until Saadi's time; which was a place for Kharabat and thugs. People attributed to Qalandar were called "Qalandari", not Qalandar. This word is a form of "Calandar20", meaning "Calangar21 “and "Langar22"; these were also the gathering places of Rendans and thugs.41 Qalandar, as Shafi'i Kadkani shows, was the name of the place until the seventh century; That is, where the Qalandarians lived; Of course, Qalandar was more than a place of asceticism and worship, it was a gathering place for the people of Kharabat, Rendan and Qalashan23.42 Manuchehri Damghani in 430 AH considers the ruins as a casino and Saadi as a wine cellar, and Khajeh Rashid al-Din Fazlullah in his book "The History of Mubarak Ghazani" does not consider the ruins as a brothel where all the evil people gathered.

Langar is used in Dehkhoda dictionary to mean the means of keeping a ship and in Anandraj culture it also means beggar and poor. In the “culture of Nezam", Da'i al-Islam considers the word Langar in Sanskrit and considers it to consist of two components: "Lan + Agar", "Lan" means to give and "Agar" means house, and in general it means to give a house and It is charity. The use of this word was more common in eastern Iran and India and was also used in Turkey.

Thus, in the evolution of Iranian architecture, tombs can be considered as one of the important institutions that have played a significant role in the spread of religious thought and prejudice. In some cases, it was even a political base for influencing the people, because these tombs had become sacred buildings and places, and in many cases, even vows were offered to the "Vali" in cash or non-cash.

14Prison.

15Asylum for the poor and homeless.

16It is a term used to refer to the recitation of the Qur'an or a prayer for the dead. This may be done at a funeral home, a pilgrimage, or anywhere else.

17 اهل دویرته و دوایرت حوله

18 وکأ

19Ruins

20کالندر

21 کالنگر

22لنگر

23Qalashan (قلاشانin Persian) in the apparent sense refers to homeless people and thugs, but in fact it refers to those who are happy and in love and has lost interest in the world.

Sufism began in the late first century and early second century AH. At the beginning of the fifth century AH, it reached its peak by people such as Abolhassan Kharghani (352-425 AH) and Abu Sa'id Abu al-Khair Mihani (357-440 AH). Abu Sa'id was one of those who led the systematization of Sufism because a large number of Sufis did not have a specific gathering place and the ḵānaqāh settlement can be considered one of the achievements of Abu Sa'id. After Abu Saeed, Abu Hamid Mohammad Ghazali (450-505 AH) became one of the greatest jurists and theorists of Sufism and had an important role in strengthening its position in the eyes of the people of Sharia and the government. Of course, the Seljuks themselves respected the ḵhānaqāh settlement, and even Khajeh Nizam al-Mulk built a ḵhānaqāh for them. But with the attack of the Ghaznavid Turkmens on Khorasan, many Sufi scholars stained their blood and killed them.43 This attack had such a profound effect on the material and spiritual life of the people in eastern Iran that it was called the end of happiness and the beginning of unrest in the land of Muslims and the time of "only the religion and the inept Muslim".13 Martin Lings considers Sufism to be nothing but Islamic mysticism and introduces it as the strongest tidal current in Islamic revelation that "Sufism is both valid and effective".1

Stages of Sufism in Islam

In his article "An Analysis of Sufism with Emphasis on the Dhahabiyah Sect", Hossein Dezfuli considers the stages of Sufism in Islam from the Sunnis, which begins as a social current from the heart of society and eventually expands in an eclectic and deviant manner. The stages of Sufism include three stages that appear in different processes. Sufism is in the beginning stage which starts from the step of Sunnah and opposes Shiism and expands with the thoughts and ideas of Hassan Basri or Abu Hashem Kofi or Sufyan Thori and only one current. Includes society without having scientific theories about Sufism.

In the second step, Sufism appears as a relative and empathetic current due to the theories of people such as: Siraj, Qushayri, Ain Al-Qodat Hamedani, Mohi-ud-Din Ibn Arabi, Qonavi, etc., and appears as a kind of Sunni-Shiite Sufism. Although these people did not believe in the direct leadership of Imam Ali (as), they believed in him as the “Qutb al-Aqtab24" and the head of the Sufi dynasty. Even in the issue of Mahdism, mystical and formative guardianship, and even jurisprudential issues, this group of Sufis followed the Shiite religion more.

In the third step, we see eclectic Shiite Sufism, which ultimately leads to the separation of Sufism and Shiism. In this step, the eclecticism of Sunni and Shiite teachings that can be seen in the sects of Nemat Elahi from the time of Shah Nematullah Vali and the sect of Zahabiya from the time of Seyyed Abdullah Barzeshabadi. In the final step, mysticism and Sufism are separated from each other, which were dedicated to the era of the late Sheikh Ansari, Mullah Husseinghli Hamedani, Ayatollah Behjat and Seyyed Ali Ghazi Tabatabai (Diagram 2).

One of the best examples to be examined is the ḵānaqāh of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili. This building has unique features in terms of location and texture, which can finally be found in the sense of mystical interpretation and symbolic components in an unparalleled unity.

24Great leader, Supreme guide

Burckhardt writes about Islamic art: “for a Muslim, art to the extent that is beautiful, without having any sign of mental or individual inspiration, is only the “evidence and proof of Allah’s existence”; its beauty like a sky full of stars should be impersonal. In fact, Islamic art reaches grace in a way that it seems to be independent from its creator, its glories and faults are evaded in front of general character of forms”.44

Each work of art tries to achieve a specific thinking.45,46 Violet Ludouk also considers the work of art to be the product of thought, and thinking is nothing but a conceptual and symbolic connection with the work of art, that is, in better expression, the same concept of experience and meaning of James Ackerman that engages the audience through the experience of being in space. The presence of an intermediate link between meaning and fundamental thinking that shapes the architectural work. In the Table 1 below, we can deduce the relationship between monastic thinking, which results from mysticism, in the architecture of Sheikh Safi ḵānaqāh.

In the design of the building, the architect evokes a kind of journey that starts from the square and ends at the dome, which is a symbolic connection with the concept of unity of existence and esoteric drawing of "Huwa25". Imam Mohammad Al-Ghazali considers two types of journeys for human beings, one is the apparent journey which is in the material world and the other is the inner journey and departure which he prefers this journey. "Know that travel causes disgust and grows to achieve the desired and travel is of two kinds: one that is the most apparent to go from home and homeland to the desert and the second that was in the heart of the journey from the bottom of the saflin to the kingdom.22 With this statement, Al-Ghazali considers knowledge to be dependent on journey and behavior, and the artist achieves it in his heart, because he does not design with enthusiasm unless his heart is dependent on divine knowledge.49 Sheikh Mahmoud Shabestari in "Golshan Raz" confirms this:

"Because he was a traveler, who is the traveler? / Who can say that he is a complete man?"

In other words, who is the passenger on the way / someone tries to be aware of his origin

The traveler was to pass soon / to clear himself like fire from smoke”.50

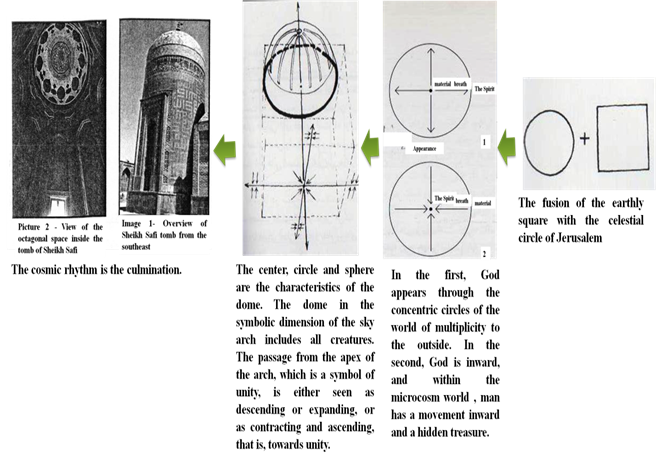

Thus, one of the most basic principles that can be mentioned in Iranian architecture, especially religious architecture, is the relationship between the realm of the heavenly world and the realm of the earth. In this view, architecture should be a representation of the upper world, and for this to happen, the only language of sacred art is symbolism, which is reflected in the aspects of architecture. "Memarian" says about the architect, the work and the world of mysticism: "Man of the Islamic mystical world has a special attitude towards the Creator of the universe and its components. In this world, everything but the essence of truth moves towards him. This person or expert or architect lives in a society that is governed by the principles of tradition. These principles are in him and within him, and guide him towards the ultimate goal” (Diagram 3).

In the view of Eastern mystics, the architecture of the terrestrial world is a picture of the exemplary world. The world of Meisal is a world between the world of meaning and the world of matter; therefore, this world is a barrier between the world of meaning and the world of matter, and therefore it can be called the "world of purgatory". Therefore, this world is the world of form, so with the other two worlds, in general, it provides three worlds: the world Meaning, the world of form and the world of matter.

The building of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili is one of the historical and religious buildings of the middle of the eighth century AH. This complex was originally the ḵānaqāh and residence of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ishaq Ardabili, the great Sufi of the seventh century AH, who taught his followers in this place. This house was developed after the death of the sheikh by his children and later by the order of the Safavid kings and new buildings were added to it.51

This building includes a collection of tombs of Safavid princes and rulers. This building includes several buildings named as the tombs of Sheikh Safi, Shah Ismail, Sultan Haidar and Junaid, Chinikhaneh, Jannat Sara Mosque, Khaneghah, Chelekhaneh, Shahidgah, Cheraghkhaneh. "The construction of the above collection started today in the time of Shah Tahmasb Safavid and then was completed in the period of the next kings. During the reign of Shah Abbas I, a very exquisite collection of porcelain (made in China) and a precious library and porcelain house were added to it. One of the most exquisite objects in the tomb of Sheikh Safi is the famous carpet of Ardabil, which is currently kept in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London”.52 Careful design of Iranian carpets confirms that the designer's intention was not only to create a work of art. Rather, behind its appearance, there is a very deep thought in order to explain the myths and create a symbol. This is the same feature of Iranian art; Which has two dimensions, one body and face and the other dimension of meaning or content; The face is the apparent beauty of the design and color that can be seen with the eyes, and the meaning is the same hidden and sometimes unconscious thought of a person who begins to create a visual front with different designs.53 The main part of Sheikh Safi's collection is "Gonbad Allah Allah", the architect of which is a person from Medina. According to Olearius, he had implemented the plan of Sadr al-Din Musa.54

Although the various buildings in the complex were completed during different periods, it is said that their design was inspired by a design that miraculously occurred to the architect. Adam Olearius writes that: "The role and design of the building was miraculously given by Sheikh Sadr al-Din himself. He ordered the master to close his eyes and the master did so and in his dream he was inspired by the image of a mansion from which he had to build from it ”.55 The map shows the subset of Sheikh Safi, but before entering into the discussion we must be familiar with mystical thinking and its stages (Figure 5).

25God means in the Qur'an

There are different levels in "Tariqat" that it is necessary to know the relationship between these levels and the stages designed in the collection of Sheikh Safi al-Din, it is necessary to know each of these levels and stages. Siraj Tusi considers mystics to have seven positions, which are:

But Attar's view is more influential among different experts, and the evidence in Sheikh Safi al-Din's collection shows that these steps are more closely related to Attar's views. In his poems, Attar mentions seven "Vadi26" and after these steps, he mentions a level that can no longer be named, and there other methods and principles lose their meaning:

"The Vadi of wanting is the beginning of work / The Vadi of love is, from then on, unstoppable So the third Vadi is that Wisdom / So the fourth Vadi is a needless adjective

There is the fifth Vadi of pure monotheism / then the sixth Vadi of astonishment

The seventh is the Vadi of poverty and annihilation / after this there is no way"

26Land, space, place

The first Vadi (wanting)

First, entering the Sheikh Safi complex, we enter the first square or courtyard. A field that is a public arena and everyone has an equal share in its use, and this is the first Vadi, or wanting or Sharia, which creates a way for man to live in this world in a healthy way and according to God's will. The square with the shape of a rectangle is reminiscent of the microcosm world and the material world is earthly, it is the world of multiplicity. Because the square is a symbol of the earth. The square of the earth is a bed on which the transcendent wisdom acts in order to re-integrate the earth with the circle of the sky. It is at this point that one begins one's journey and prepares to be free from the pleasures of the world. At this stage, he begins to ascend and enters the seven stages, which is an objective example in Sheikh Safi ḵhānaqāh. It also leads to alleys that distinguish it from other courtyards. Even the gate to enter and exit this courtyard is not located in the main axis. It is as if the lack of direction of the courtyard and its intermingling with urban functions, in a way, indicates the characteristics of “Vadi wants " (Figure 6&7).

The second vadi (Love)

The second Vadi is love. It is the largest and most terrifying Vadi in which a Sufi walks. The criterion of measurement and the most important element is the "Tariqa". In Sufism, love is opposite to reason, so it cannot be fully defined, because Sufism is constantly striving to evolve, and this Vadi is the second courtyard Figure 9, which is a kind of connection between the microcosm and the higher world. In Sheikh Safi, the second courtyard plays the role of the second Vadi, in which fireworks were performed Figure 8, and fire is like fiery love that draws the lover to the beloved. The seeker is exposed to a fire that burns and is drowned in light. As Rumi says about love:

"Wisdom in its description, the donkey fell in the flower / the description of love and a lover also said love"

The third vadi (Wisdom)

”Chelekhaneh" and the altar27 is the third Vadi. The seeker comes to the status of Wisdom after passing the Vadi of love. According to the scholars, Wisdom is the same as cognition, and every scholar is aware of God, and every mystic is a scholar. This Vadi is associated with self-austerity and the destruction of worldly desires and greed, and is always in obedience to God Almighty. The altar is a small space in which human attention is drawn to the sky, as if the truth of wisdom has tried to manifest here. From behind a small door, some of the space of the field or inner courtyard, which can be called the field of presence, can be seen and invites people. But passing this stage, the reverse of the previous stage, is not accompanied by speed and acceleration, but by delay and reflection. From behind a small door, some of the space of the field or inner courtyard, which can be called the Saahat28 of presence, can be seen and invites people. But passing this stage, the reverse of the previous stage, is not accompanied by speed and acceleration, but by delay and reflection. Thinking about the meaning of the word altar also reveals points to us. Sacrifice can be traced back to the story of the sacrifice of Ishmael by Abraham. Here, Abraham, after learning the truth of the dream he had seen, sacrificed his son and brought him to the altar. This is the characteristic of the position of knowledge that man gives up his desires with full awareness of God.

The fourth vadi (Needless)

In this Vadi, spatial and temporal beings, the greatest dimensions they can have, are drawn into the allegory of humiliation: "Two worlds turn to pebbles", "planets and stars become leaves" and "parts and whole to sometimes". In this Vadi, the needlessness of everything either leads man to nothingness or leads him to the truth and mystery in how he views the earth and time, and nothing else (Figure 10&11).

The Saahat or inner courtyard with its special tiles and proportions gives the audience the feeling of reaching. Especially when, after passing through the altar, he acquaints us with the dome of "Allah Allah" and obtains satisfaction from the current situation. Here, the play of colors and the presence of water, sky and tiles together leave no other place for the world we came from, and the feeling of needlessness from everything we have experienced so far manifests in us. In the southern part of the courtyard was the "Dar al-Hadith Saahat" where jurisprudential and educational issues were discussed. On the other side of this courtyard and in front of Dar al-Hadith, there was Jannat Sara, which is the place of Dervish dance and has a square stone. This place was later known as Jannat Sara Mosque, but it did not have an altar and was not built in the direction of Qibla. In fact, Dar al-Hadith and Jannat Sara formed the two jurisprudential and mystical wings of the people of Tariqah in order to reach the truth, and it was in this position that knowledge and circumstances were presented to the seeker. The naming of this courtyard as its own Saahat indicates that this is the Saahat of presence and different aspects of truth are presented to the seeker and make him unnecessary. But crossing this yard and the possibility of entering the fifth place can only be done through one event, which happens here in the form of an entrance in the corner of this yard. The entrance here, unlike the geometry of various Iranian entrances, is not located in the main axis of the courtyard, but is located in a corner of the courtyard at the farthest point from the dome of "Allah Allah". This is what can be related to what happened to cross the needless Vadi (Figures 12&13).

The fifth vadi (pure Tawhid29)

Tawhid in the word is a ruling that something is one and knowing it is one in the same. In the term of the people of truth, it is the abstraction of the divine essence from what comes in the imagination or understanding or dream or illusion or mind. Before entering the “Jannat Sara " space, there is an Saahat which is the space of pause and transcendent wisdom, which acts in the direction of the integration of the celestial circle, which is the space of the Jannat Sara. For this reason, the Vadi of Needless and monotheism can be seen in the space of Jannat Sara, a space that is octagonal, which confirms the principles of unity of existence30 and emphasizes the "word of God". Unificationism is something that the seeker is moving towards from the day of his awakening, and this is the journey of Imam Mohammad Ghazali and the Substance theory of Mulla Sadra that can be seen in the whole architectural structure of Sheikh Safi. As a result, pushing the seeker to a point is at its peak, which is also an example of the architect's work in designing such spaces.

"The point appeared in the circle and was not / but that point indicated the circle

The point is around the circle / to the person who walked the circle

The first and the last joined / the point as the end of the circle went When the circle was finished, Pergar / after that, he easily rested "From the lyric poems of Shah Nematullah Vali (15th century) (Figure 14).

The sixth vadi (astonishment)

This Vadi is bewilderment, and in the term of Ahl al-Allah it is something that enters the hearts of mystics while contemplating and attending. Attar quotes the following in Mantiq al-Tair about this valley:

“After this Vadi, you will be amazed / you will be in constant pain and regret

Every breath here is like a razor, Tora / every breath here makes you regret

But I have no awareness of love / I have a heart full of love and empty “

"Dar al-Hifaz and the play of light and shadow on the ceiling, which brings with it all the patterns and decorations, connect the earth and the sky with a carpet with a beautiful pattern that reflects the patterns on the ceiling of this space ". (Figure 15) The qualitative nature of all geometric shapes, as seen in the Dar al-Hifaz carpet, tends to a central purpose. The qualitative nature of all geometric shapes, as seen in the Dar al-Hifaz carpet, tends to a central purpose. The central emblem is a set of pendants with spiral branches like a cosmic tree in praise of the Garden of Eden. These Islamic motifs are a combination of both time and positive space in the action of geometric patterns that lead the suspension to a single point.

Figure 15 Dar al-Hifaz carpet, the garden of paradise and explaining the concept of eternity and infinity. Source: Author.

The seventh vadi (poverty and Fana31)

The seventh Vadi is the Vadi of poverty and destruction. Abu Turab Nakhshbi said: The truth of wealth is that you do not need anyone like you and the truth of poverty is that you are in need of anyone like you; But Fana: In Sufi terminology, the fall of the ugly attributes of the seeker is achieved by adding austerity, and another type of Fana is the lack of feeling of the seeker.56 And this Vadi is the last stage of the seeker who enters when the seeker enters a single space and and acquires his knowledge in the position of annihilation in the way of God. At this stage, pure totality pervades the seeker, and the only thing that can show such thinking is the dome-shaped and circular form that guides the seeker from the multiplicity of the microcosm world to the unity of the world of multiplicity. The dome is a representation of the dome of Mina or the seventh sky or Horaqlia and in the words of Balkhari Ghahi "represents the inclusion of all creation (by the sky) and this point corresponds to the meaning that it is the circle of wholeness and perfection". The color and atmosphere of the dome of "Allah Allah" is manifested as the lover of the beloved and is like the union and connection of the seeker to the truth. The seeker has reached the end of the road and is finishing his spiritual journey, and the ḵhānaqāh is a place of pilgrimage and a journey from God to the people. (Figure 16)

Figure 16 The concept of dome in Islamic architecture with reference to the dome Allah Allah as the seventh Vida. Source: Author.

27An altar is a structure upon which offerings such as sacrifices are made for religious purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches and other places of worship.

28Territory, scope, square, yard, courtyard,

29Tawhid (Arabic: توحيد, tawḥīd, meaning "unification or oneness of God as per Islam (Arabic: الله Allāh)"; also romanized as Tawheed, Touheed, Tauheed or Tevhid) is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single most important concept, upon which a Muslim's entire religious adherence rests. It unequivocally holds that God as per Islam (Arabic: الله Allāh) is One (Al-ʾAḥad) and Single (Al-Wāḥid).

30Sufi metaphysics

31"Fana" literally means nothingness and destruction. The opposite of survival, which means to remain and remain.

What was said in this article about the relationship between the way of thinking and the architecture of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili can be summarized in the Table 2 below.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2023 Asadi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.