eISSN: 2379-6367

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 2

1Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, Canada

2Infectious Diseases/Internal Medicine, Horizon Health Network, Canada

3Clinical Resource Pharmacist, Infectious Disease, Horizon Health Network, Canada

4Chief Statistician, Horizon Health Network, Canada

Correspondence: Andrew Dalziel, Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, 135 MacBeath Ave, Suite 6400, Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada, Tel (902) 789-6575

Received: March 01, 2018 | Published: April 18, 2018

Citation: Dalziel SA, Ghaly A, Smyth D, et al. The management of outpatient cellulitis at the Moncton hospital before and after the initiation of a clinical treatment pathway. Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2018;6(2):138-147. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2018.06.00170

Introduction: Antimicrobial stewardship is a coordinated effort to improve the appropriate use of antimicrobials. Inappropriate antibiotic use is a major contributor of emerging antibiotic resistance. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are commonly used for moderate to severe skin and soft tissue infections when narrower-spectrum options would be adequate.

Objective: Objectives included characterizing the antibiotic prescribing for the management of uncomplicated cellulitis in an outpatient setting. In addition, a clinical treatment pathway (CTP) was developed and its use was evaluated.

Methods: The study was a retrospective chart review looking at antibiotic prescribing in The Moncton Hospital Emergency Department and included patients treated before and after the introduction of an outpatient management pathway for cellulitis. The pathway recommended once daily probenecid 1g followed by cefazolin 2g IV. Antibiotic usage, treatment failure rates, and adverse events were compared between the two groups.

Results: In the pre-intervention group; 3 patients received cefazolin, 50 received Ceftriaxone, and 1 received Levofloxacin. After the introduction of the clinical treatment pathway there was an absolute increase of 53.8% (n=35) in the use of cefazolin and absolute decrease of 53.7% (n=23) in the use of Ceftriaxone. Both results were statistically significant (p<0.001). In eligible patients, the treatment pathway was utilized 61.1% of the time.

Conclusion: The introduction of a clinical treatment pathway outlining the preferential use of once daily cefazolin plus probenecid for the treatment of outpatient cellulitis led to a significant increase in the use of cefazolin, and decrease use of Ceftriaxone, thus demonstrating a positive stewardship effect at a local level.

Keywords: cellulitis, antibiotic stewardship, skin & soft tissue infections, beta-hemolytic Streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, antibiotic therapy

Cefazolin: a first-generation cephalosporin antibiotic

Ceftriaxone: a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic

Cellulitis: recent onset of soft-tissue erythema associated with signs of infection that include ≥1 of the following symptoms: pain, swelling, lymphangitis, and fever

CTP: clinical treatment pathway

IV: intravenous

Probenecid: a uricosuric medication that prevents the excretion of cefazolin in the urine

Broad spectrum therapy: an antibiotic that has a wide range of activity against disease-causing bacteria

Narrow spectrum therapy: an antibiotic that has a narrow range of activity against disease-causing bacteria

Primary outcomes: The type and duration of antibiotics used to treat outpatient cellulitis and adherence to the clinical order set

Secondary outcomes: Treatment failure and rate of C. difficileinfection within 30 days of treatment.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America defines antimicrobial stewardship as a coordinated effort to improve and measure the appropriate use of antimicrobials by promoting the selection of the optimal antimicrobial drug regimen, dose, duration of therapy, and route of administration.1 One of the recommendations they make is through the use of guidelines and clinical treatment pathways that involve evidence-based approaches to treating common infections. This aims to improve prescribing patterns while trying to avoid the unintended consequences such as antimicrobial resistance, adverse drug events, and cost.1 Skin and soft tissue infections are a common reason for patients to seek medical care.2 Cellulitis is generally defined as recent onset of soft-tissue erythema associated with signs of infection that include ≥1 of the following symptoms: pain, swelling, lymphangitis and fever.3 Many of these patients are systemically well and can be managed in an outpatient setting.

A retrospective chart review in one Canadian city with 5 urban Emergency Departments reported a principal diagnosis of cellulitis in almost 4000 people in just one year. This represented 1.3% of all ED visits.2 These infections are generally treated empirically as microbiologic culture is difficult and not practical to obtain.4 Although difficult to isolate a pathogen, the microbiology of uncomplicated cellulitis remains fairly well known with Staphylococcus aureus and beta-hemolytic Streptococci species being the most common causative organisms.5‒7 Traditionally, moderate to severe cases of cellulitis require intravenous antibiotics. One of the first line treatments is cefazolin, a first-generation cephalosporin administered intravenously every 8 hours due to its short half-life.8 This provides relatively narrow spectrum, targeted therapy, against the most common bacteria responsible for cellulitis.8‒10

The ability to manage moderate cellulitis in an outpatient setting using parenteral therapy was demonstrated in several trials investigating the effectiveness of a once daily injection of Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin, compared to cefazolin that required dosing every 8 hours. Study authors found that once daily administration of Ceftriaxone was highly effective in treating skin and soft tissue infections because of its broad spectrum of activity and safety, as well as a huge cost saving measure allowing the option of outpatient treatment.11‒13 Although Ceftriaxone-dosing frequency makes it a convenient choice, it is unnecessarily broad in spectrum when compared to cefazolin. Recently there has been a worldwide emphasis on antibiotic resistance with the development of “superbugs” resistant to many common antibiotics.14 Other unintended consequences of antibiotic overuse include the depletion of normal gut bacteria, potentially leading to secondary infection with Clostridium difficile. This infection is associated with extensive use of broad spectrum cephalosporins such as Ceftriaxone.14 The impact of these infections on the health care system is massive with one review article estimating an annual cost for the management of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States to be approximately $800 million.15

In an effort to reduce unnecessary use of broad spectrum antibiotics there has been a push to use once daily cefazolin with probenecid in treating outpatient cellulitis. Probenecid is a uricosuric agent that inhibits the renal clearance of cefazolin thereby prolonging its half-life.16 Studies have shown that in combination, cefazolin concentrations remained above the minimum inhibitory concentration for the twenty-four hour dosing interval.17‒19 This leads to a reduction in the number and frequency of intravenous infusions and also leads to less resource utilization. There have been two randomized controlled trials to date that compared the efficacy of once daily cefazolin plus probenecid versus once daily Ceftriaxone in the management of outpatient cellulitis. Both authors concluded that once daily cefazolin plus probenecid was equally efficacious compared to Ceftriaxone.20,21 Many Emergency Departments in Canada have adopted this approach to managing outpatient cellulitis requiring intravenous antibiotics.2 A separate retrospective study identified chronic venous disease as a risk factor for treatment failure with once daily cefazolin plus probenecid.22

The objectives of this study were:

Study design

This is a retrospective before and after intervention study. The goal was to identify at least 50 patients that received intravenous antibiotics both before and after the intervention. The before intervention analysis consisted of a retrospective chart review identifying patients that were discharged from the Emergency Department at The Moncton Hospital with a diagnosis of cellulitis which was considered severe enough to require the patient to return daily for intravenous antibiotics. A clinical treatment pathway for the outpatient management of cellulitis with intravenous antibiotics was produced and made available before the second half of data collection. The treatment pathway had defined usage criteria, exclusion criteria, and outlined management using once daily cefazolin plus probenecid (Appendix 1). The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the chart review aligned with the treatment pathway to assess its applicability. A standard data collection form was used to collect demographics, co-morbidities, antimicrobial treatment, inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment failure, rates of C. difficile infection, and use of the CTP (Appendix 2). The chart review identified patients from September 2015 to February 2017. The CTP was made available in May 2016, along with hospital promotion and physician education. Prior to release of the CTP, feedback was obtained from the Departments of Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and Pharmacy.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included:

Secondary outcomes included:

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software, version 3.2.5 ©GNU General Public License, 2016. A MANOVA test has been used for comparing demographics. A chi-square test was used to compare the amount of cefazolin and Ceftriaxone being prescribed, before versus after implementation of the CTP. A two-way ANOVA test was used to compare failure rates and C. difficile infection in patients receiving IV Ceftriaxone versus IV cefazolin. Research Ethics Board approval was granted through the Horizon Health Network.

A total of 295 charts were reviewed during the study period. Of these charts, 222 patients were diagnosed with cellulitis and treated with an antibiotic as an outpatient. Intravenous antibiotics were given to 113 (50.9%) of these patients, with 54 in the pre-CTP group and 59 in the post-CTP group, while the rest received oral antibiotics. The remaining patients did not meet diagnostic inclusion criteria or were admitted for treatment. Baseline characteristics of patients receiving IV antibiotics were not statistically different between the pre- and post-CTP groups (Table 1). The median ages were 54.5 versus 57. Co-morbidities were similar with diabetes mellitus present in 12% versus 15%, chronic kidney disease in 2% versus 3%, and immunosuppression in 2% versus 1%. One patient in the pre-group had a documented allergy to cefazolin while none in the post group did.

Characteristic |

Before intervention |

After intervention |

Median age–years |

54.5 |

57 |

Male sex–no. (%) |

31 (57.4) |

32 (54.2) |

Diabetes Mellitus–no. (%) |

12 (22.2) |

15 (26.3) |

Chronic Kidney Disease–no. (%) |

2 (3.7) |

3 (5.1) |

Immunosuppressed–no. (%) |

2 (3.7) |

1 (1.7) |

Allergy to Cefazolin–no. (%) |

1 (1.8) |

0 (0) |

Table 1 Baseline demographics

Baseline characteristic of the patients included in the study. There were 54 patients in the before intervention group and 59 patients in the after intervention group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in any characteristic using a MANOVA test with p=0.83.

Primary Outcomes

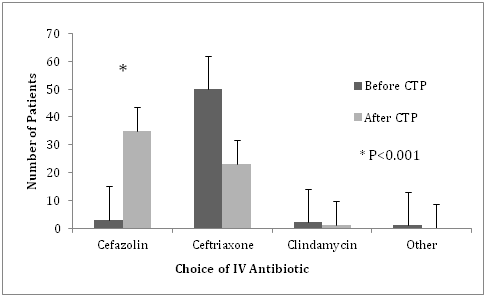

In the pre-CTP arm, there were 54 patients that received IV antibiotics, consisting of cefazolin (3), ceftriaxone (50), clindamycin (2), and Levofloxacin (1). There were two patients in this arm that received double coverage with clindamycin, and Levofloxacin, respectively, in addition to their cephalosporin. The median duration of IV therapy in the pre-CTP group was 4 days (Table 2). In the post-CTP arm, there were 59 patients that received IV antibiotics, consisting of cefazolin (35), Ceftriaxone (23), and clindamycin (1). The median duration of IV therapy was 3.5 days (Table 2). There was a statistically significant increase in the use of cefazolin, 3 patients versus 35 patients (p<0.001), corresponding to a 53.8% absolute increase, after the introduction of the CTP. There was also a statistically significant decrease in the use of Ceftriaxone, 50 patients versus 23 patients (p<0.001), corresponding to 53.7% absolute decrease, after the introduction of the CTP (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Intravenous antibiotic usage.

Use of Cefazolin and Ceftriaxone before and after the introduction of a clinical treatment pathway outlining preferential use of once daily cefazolin plus probenecid for the treatment of moderate to severe cellulitis. There was a significant increase use of cefazolin and decrease use of Ceftriaxone (*p<0.001) after the introduction of the clinical treatment pathway. Error bars represent standard error within both groups.

|

Before intervention |

After intervention |

P-value |

Number of patients |

54 |

59 |

|

Cefazolin |

3 |

35 |

P<0.001 |

Ceftriaxone |

50 |

23 |

P<0.001 |

Clindamycin |

2* |

1 |

P=0.831 |

Levofloxacin |

1* |

0 |

P=1.000 |

Median duration of therapy (days) |

4 |

3.5 |

P=0.719 |

Table 2 IV antibiotic usage

Choice of intravenous antibiotic prescribed before and after the introduction of a clinical treatment pathway outlining preferential use of once daily cefazolin plus probenecid. *There were two patients in the before intervention group that received double coverage; one patient received clindamycin and the other received Levofloxacin in addition to a cephalosporin.

In the post-CTP arm, there were 53 (out of 59) patients eligible for therapy with cefazolin based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the treatment pathway (Appendix 1). Of these 53 patients, 34 (64.1%) were started on the protocol. The protocol was only deviated from once where a patient was prescribed oral clindamycin during day 3 of cefazolin therapy due to “minimal improvement” as documented on the chart. The majority of follow up for patients on the CTP was completed in the Emergency Department (83.1% of patients) by either the Emergency Room Physician or Nurse Practitioner on duty. Various other services provided follow up for the remaining patients: Infectious Disease (3.4%), other (10.2% consisting of Family Medicine, General Surgery, Dermatology, Gynecology, and Ophthalmology), while 3.4% of patients were not followed up.

Secondary outcomes

There was no statistically significant difference in rates of treatment failure defined as admission to hospital within 30 days with worsening or similar infection in that area or escalation in antibiotic therapy when comparing cefazolin versus Ceftriaxone (Table 3). There were no cases of diagnosis of C. difficile infection in either group within 30 days of antibiotic therapy (Table 3).

Outcome Measure |

Cefazolin* |

Ceftriaxone* |

P-value |

Treatment Failure |

|||

Admission–no. (%) |

5 (13.1) |

10 (13.6) |

P=0.781 |

Change of therapy–no. (%) |

7 (18.4) |

11 (15.0) |

P=0.831 |

C. difficile infection–no. (%) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

P=1.000 |

Table 3 Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures comparing patients who received cefazolin versus Ceftriaxone. Both groups include patients from before and after the introduction of the treatment pathway. Admission was defined as admission to hospital within 30 days of initial diagnosis, for cellulitis or another infection at that same site. Change of therapy indicated an escalation or change in intravenous antibiotic therapy within 30 days of diagnosis. C. difficile infection was defined as occurring within 30 days of receiving antibiotics as evidence from microbiology results in the electronic medical record.

The microbiology of skin and soft tissue infections remains primarily beta-hemolytic Streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. Historically patients were admitted to the hospital for frequent intravenous infusions of antibiotics when treating moderate to severe cellulitis until the use of once daily administration of Ceftriaxone, a broad spectrum third-generation cephalosporin, was favored.11‒13 This therapy allowed outpatient treatment without the need to hospitalize patients but with the growing emergence of antibiotic resistance it is desirable to use more targeted, narrow spectrum therapy. In recent years there has been a push to use once daily cefazolin with probenecid for the management of outpatient cellulitis. Cefazolin provides excellent coverage for the usual pathogens without the unintended drawbacks of broad spectrum coverage.23 When given with probenecid, a uricosuric agent that prevents its renal elimination thereby prolonging its half-life, it allows for once daily dosing instead of traditional dosing every eight hours, facilitating convenient outpatient therapy.18‒20 The purpose of this study was to characterize current patterns in antibiotic prescribing for the treatment of cellulitis at the Moncton Hospital, and also to assess the effectiveness of a clinical treatment pathway outlining optimal treatment of these infections. We hypothesized that the majority of patients being treated at The Moncton Hospital were receiving unnecessarily broad spectrum antibiotics and that with the introduction of a clinical treatment pathway outlining therapy with once daily cefazolin; we would see a shift in this prescribing pattern.

The results demonstrated that the majority of patients (92.6%) received Ceftriaxone while only a small minority (5.6%) of patients received cefazolin before the introduction of the CTP. This confirmed the overwhelming preference for Ceftriaxone in this population of patients treated for cellulitis. We suspect this is primarily due to once daily dosing of Ceftriaxone versus dosing every eight hours with cefazolin. After the introduction of the CTP, cefazolin was used in 59.3% of patients while Ceftriaxone use fell to 39.0%. This represented a significant increase in the use of cefazolin and a significant decrease in the use of Ceftriaxone. We attributed this in part to the use of the clinical treatment pathway. Looking at treatment outcomes, there was no significant difference in rates of treatment failure comparing cefazolin versus Ceftriaxone. This aligns with prior research indicating their similar efficacy in treating cellulitis.20,21 Although Ceftriaxone is associated with an increased risk of secondary C. difficile infection24 we did not see a difference in this outcome compared to cefazolin. This is perhaps due to the overall low numbers included in the study. When comparing costs, the hospital price of Ceftriaxone and cefazolin were similar therefore no cost saving measures were recorded after the CTP. It should be noted that there are extremely low rates of MRSA colonization in Moncton, NB, which is reflected by the low use of MRSA active antimicrobials during the study. A limitation of this study was that it was retrospective in nature. There was no randomization of antibiotic therapy and could therefore introduce selection bias on the part of the treating clinician based on how severe they determined the infection to be. Small study numbers may have been insufficient to detect differences in efficacy and adverse events. Data collection also relied upon review of paper and electronic charting which is prone to error or omission.

There is a growing trend of antimicrobial resistance worldwide due to overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The concept of antimicrobial stewardship was developed to help combat this problem, promoting optimal antimicrobial therapy and monitoring. This study supported the introduction of a clinical treatment pathway outlining the treatment of outpatient cellulitis with the use of once daily cefazolin plus probenecid as a narrower alternative to once daily Ceftriaxone. The study also demonstrated a measurable change in prescribing patterns when the CTP was introduced leading to more use of cefazolin and less use of Ceftriaxone in managing outpatient cellulitis.

I would like to thank Dr. Ahmed Ghaly, Dr. Daniel Smyth, and Timothy MacLaggan for their guidance, support, and manuscript revision in this study. I would also like to thank Dr. George Stoica for statistical analysis.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

©2018 Dalziel, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.