eISSN: 2379-6367

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 4

Department of Pharmacy, VA North Texas Health Care System, USA

Correspondence: Frank Chen, Associate Chief of Pharmacy, Bonham Operations, Adjunct Faculty Clinical Instructor/Assistant Professor-UT Austin/Texas Tech, VA North Texas Health Care System Pharmacy Service, Sam Rayburn Memorial Veterans Center, 1201 E. 9th St, Bonham, Texas 75418, USA, Tel 9035836253

Received: June 22, 2017 | Published: August 11, 2017

Citation: Chen F, Rosemeier K, Weideman R. Safety and efficacy of dofetilide therapy in a veteran’s affairs population: the DT-VAP study. Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2017;5(4):131-138. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2017.05.00127

Purpose: Data on Dofetilide use in the veteran population remains limited. In clinical trials, Dofetilide has been shown to successfully cardiovert ~30% of atrial fibrillation (AF) patients, while demonstrating variable sinus rhythm (SR) maintenance rates over long-term follow-up. This study investigates Dofetilide therapy in a Veterans Affairs population.

Methods: We included patients 18years of age or older who initiated Dofetilide at the Dallas VA Medical Center between 1/1/2007 and 10/1/2011 in this retrospective cohort study. Efficacy endpoints were incidence of successful cardio version and maintenance of SR through 1months after Dofetilide initiation. Safety end points included all-cause mortality, changes in QTC, frequency of shocks from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), Dofetilide dose changes, and reasons for withdrawal from Dofetilide.

Results: Overall cardio version to SR with Dofetilide was 72%, with 56% in combination with direct current cardio version (DCCV) and 16% with Dofetilide alone. Long-term SR maintenance rates appeared somewhat similar starting at the thirdmonth (~38%) and trended upwards through 12months (~75% at best) regardless of whether patients successfully cardioverted to SR during Dofetilide initiation. Patients who were not in active AF during initiation appeared to have lower long-term SR maintenance rates (~40% at best). Three patients died during the study, but there were no cases of torsades de pointes. Sixty-seven percent of Dofetilide dose decreases were due to QT prolongation, and ~33% of patients with an ICD received at least one shock during the study.

Conclusion: Dofetilide is safe and effective during initiation and long-term follow-up in the veteran population.

Keywords: dofetilide, tikosyn, veterans, VA, dt vap, efficacy, safety, cardiovert, cardio version

AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; SR, sinus rhythm; VA, veterans affairs; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; DCCV, direct current cardio version; VANTHCS, va north texas health care system; SAFIRE-D, symptomatic atrial fibrillation investigation and randomized evaluation of dofetilide; DIAMOND-HF, danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide in congestive heart failure; DIAMOND-MI, danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide in acute myocardial infarction; DT-VAP, safety and efficacy of dofetilide therapy in a veterans affairs population; EKG, electrocardiogram; VT, ventricular tachycardia; PM, pacemaker; BiV: biventricular; EP, electrophysiology

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and is the most frequent arrhythmic cause of hospitalization in the United States.1 Its prevalence is expected to increase in the future, and it is a progressive disease state strongly associated with adverse clinical outcomes such as heart failure, stroke, and death.2 AF starts off as paroxysmal in nature, however can develop into persistent AF and eventually become permanent. Although sometimes asymptomatic, AF in severe cases can cause palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, anxiety, and as some patients describe it-a feeling of impending doom or an uneasy feeling that they are going to die. All of these symptoms increase morbidity and can severely impact the patient’s quality of life. Current guidelines for managing persistent symptomatic AF and atrial flutter (AFL) include using Dofetilide (Tikosyn®) as a treatment modality for the termination of arrhythmia and maintenance of sinus rhythm (SR).3 Dofetilide is a pure class III antiarrhythmic agent that selectively inhibits potassium channels, prolonging the effective refractory period without affecting cardiac conduction.4,5 Although Dofetilide has been used in the market for over a decade, data on its use in the veteran population remain limited; sparking interest in this research project to investigate how Dofetilide use at the VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) compares to published data in available literature. Landmark trials on Dofetilide include the Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigation and Randomized Evaluation of Dofetilide (SAFIRE-D) and Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide in CHF and acute myocardial infarction (DIAMOND-HF and DIAMOND-MI) studies.6-8 Dofetilide has been shown to successfully cardiovert about 30% of AF patients to SR,6 while demonstrating variable SR maintenance rates over long-term follow-up through 12 months.6-8 We hypothesized in the Safety and Efficacy of Dofetilide Therapy in a Veterans Affairs Population (DT-VAP) trial that Dofetilide is effective in cardioverting and maintaining SR over long-term follow-up in the veteran population, and that Dofetilide can be safely used in these patients. Our objective was to investigate the safety and efficacy of Dofetilide therapy at the VANTHCS in Dallas. Incidence of successful cardio version and maintenance of SR at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after Dofetilide initiation was investigated. Other endpoints included the incidence of cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality and changes in QTC, frequency of shocks from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), Dofetilide dose changes, and reasons for withdrawal from Dofetilide. The results of this study could potentially advance clinical knowledge, improve patient care, and contribute to future research.

Design

After the study received approval from the VANTHCS Institutional Review Board, data on age, gender, weight, height, and race were collected retrospectively from patients who initiated Dofetilide and who had received at least one order for Dofetilide as an outpatient at the Dallas VA Medical Center between January 1, 2007 and October 1, 2011. Pertinent past medical history, laboratory values, electrocardiograms (EKG), and safety data were evaluated in all patients. For the study portion investigating the efficacy of Dofetilide therapy, patients were included whether or not they had active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation. Patients were then separated into those who were in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation as shown by EKG, and those who were not in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation. All patients who remained on Dofetilide therapy were entered into the maintenance phase of the study. Conversion to SR during Dofetilide initiation and maintenance of SR while on Dofetilide during the 12-month maintenance phase were both defined as having at least one EKG showing SR during time of study follow-up. For patients with active pacemakers who were in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation, successful cardio version to SR was considered if the pacemaker was turned off for at least one EKG reading and the intrinsic rhythm on the EKG showed SR. For the safety portion of the study, all patients were evaluated for the duration of time that they remained on Dofetilide. All patients were followed closely by the Cardiac Electrophysiology providers at the Dallas VA Medical Center. QTC intervals from patients were obtained and renal functions and serum electrolytes were monitored during Dofetilide treatment.

Study participants and data collection

We included all patients ≥18 years of age who initiated Dofetilide and who had received at least one order for Dofetilide as an outpatient at the Dallas VA Medical Center between January 1, 2007 and October 1, 2011. Patients were excluded if they had a Cockcroft-Gault calculated creatinine clearance of <20 milliliters per minute, active thyrotoxicosis, a QTC interval of >440 milliseconds or >500 milliseconds in patients with ventricular conduction abnormalities in the absence of ICDs or pacemakers during Dofetilide initiation, a QTC interval of >500 milliseconds or >550 milliseconds in patients with ventricular conduction abnormalities in the absence of ICDs or pacemakers during Dofetilide follow-up maintenance, a serum potassium level of <3.6 or >5.5 mill equivalents per liter, or if they were pregnant or breastfeeding during Dofetilide initiation.

The following data was collected for each patient given Dofetilide where appropriate: age, gender, weight, height, race, indication, cardio version method (Dofetilide plus direct current cardio version or Dofetilide alone), past medical history, previous history of cardio versions and ablations, prior antiarrhythmic use, concurrent health conditions, presence of implanted ICDs and pacemakers, concomitant medications, comprehensive metabolic panels, magnesium, EKGs, Dofetilide starting dose, Dofetilide dose changes, pertinent concomitant medication changes, Dofetilide stop dates, incidence of cardiovascular events, changes in QTC intervals, all-cause mortality, and frequency of shocks from ICDs.

Study endpoints

The primary study endpoint was the incidence of successful cardio version to SR and maintenance of SR at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after Dofetilide initiation. Secondary endpoints included the incidence of cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, changes in QTC interval during treatment, frequency of shocks from ICDs, Dofetilide dose changes, and reasons for withdrawal from Dofetilide.

Nominal data was analyzed using the Fisher exact test. For all analyses, a significance level of 0.05 was used.

Thirty-one patients were excluded from the study due to being given Dofetilide with QTC intervals greater than the preset exclusion criteria. Of the remaining patients, a total of 55 patients received Dofetilide during the study period and met inclusion criteria, and all 55 were analyzed. Our mean baseline patient age of 64 years appeared slightly younger than in the DIAMOND-HF, DIAMOND-MI, and SAFIRE-D studies; however our patient population also appeared to have more overall health conditions (full baseline comparisons on Table 1). Seven patients in DT-VAP were initiated on Dofetilide for suppression of ventricular tachycardia, which was not studied in the landmark trials. The DIAMOND studies also excluded antiarrhythmic use in the previous three months prior to starting Dofetilide, as well as patients with ICDs in place. More than half of the patients in DT-VAP had at least one prior cardio version attempt in the past, and about one in four also had at least one prior ablation. During the Dofetilide initiation phase of the study, about three out of every five patients pursued cardio version with Dofetilide alone, while about two out of every five patients did it with Dofetilide in combination with direct current cardio version (DCCV). A total of 25 of the 55 patients were in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation.

Characteristic |

DT-VAP (n=55) |

DIAMOND-HF (n=762) |

DIAMOND-MI (n=749) |

SAFIRE-D (n=77)† |

Age, mean in years (range) |

64 (41-82) |

70 (26-94) |

68 (34-89) |

67 (33-87) |

Gender, n (%) |

||||

Men |

55 (100%) |

546 (71.6%) |

542 (72.4%) |

63 (81.2%) |

Race, n (%) |

||||

White |

4 (72.7%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

African American |

3(5.5%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Unknown/Other |

12(21.8%) |

|||

Indication, n (%) |

||||

AF/AFL |

4 (87.3%) |

190 (25%) |

59 (8%) |

77 (100%) |

VT suppression |

7 (12.7%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Cardio version, n (%) |

||||

Dofetilide alone |

34 (61.8%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Dofetilide/DCCV |

21 (38.2%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Previous Procedure Attempted, n(%) |

||||

Ablation |

14 (25.5%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Cardio version |

29 (52.7%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Both |

11 (20.0%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Antiarrhythmic History, n (%) |

29 (52.7%) |

Excluded‡ |

Excluded‡ |

24 (31.2%) ‡ |

Sotalol |

19 (65.5%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Amiodarone |

12 (41.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Digoxin |

6 (20.7%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Propafenone |

3 (10.3%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Mexiletine |

1 (3.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Flecainide |

1 (3.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Esmolol |

1 (3.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Health Conditions, n (%) |

||||

Hypertension |

48 (87.3%) |

111 (14.6%) |

120 (16%) |

46 (59.7%) |

Hyperlipidaemia |

47 (85.5%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

CAD |

31 (56.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

CHF |

25 (45.5%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

LVEF ≤40% |

23 (41.8%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Diabetes |

20 (36.4%) |

152 (20%) |

97 (13%) |

--- |

Cardiomyopathy |

13 (23.6%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

CABG |

9 (16.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

COPD |

6 (10.9%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Implanted Device |

||||

ICD, n (%) |

17 (30.9%) |

Excluded |

Excluded |

--- |

Dual PM, n (%) |

16 (29.1%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Concurrent Therapy |

||||

Digoxin |

5 (9.1%) |

--- |

213 (28%) |

60 (77.9%) |

Mexiletine |

1 (1.8%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

ACEI/ARB |

39 (70.9%) |

552 (72%) |

445 (59%) |

46 (59.7%) |

BB |

47 (85.5%) |

72 (9%) |

266 (36%) |

|

CCB |

13 (23.6%) |

153 (20%) |

129 (17%) |

19 (24.7%) |

Nitrates |

10 (18.2%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Diuretics |

26 (47.3%) |

--- |

--- |

36 (46.7%) |

Statins |

37 (67.3%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Aspirin |

31 (56.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Clopidogrel |

7 (12.7%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

Warfarin |

42 (76.4%) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

LMWH/Heparin |

11 (20.0%) |

--- |

--- |

70 (90.9%) |

Table 1 Baseline Demographics

†In the 500mcg twice daily arm

‡Excluded in the previous 3-6 months

DT-VAP: Safety and Efficacy of Dofetilide Therapy in a Veterans Affairs Population; DIAMOND-HF: Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide in congestive Heart Failure; DIAMOND-MI: Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide in acute Myocardial Infarction; SAFIRE-D: Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigation and Randomized Evaluation of Dofetilide; AF: Atrial Fibrillation; AFL: Atrial Flutter; VT: Ventricular Tachycardia; DCCV: Direct Current Cardio Version; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ICD: Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator; PM: Pacemaker; ACEI: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor; ARB: Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; BB: Beta Blocker; CCB: Calcium Channel Blocker; LMWH: Low-Molecular Weight Heparin

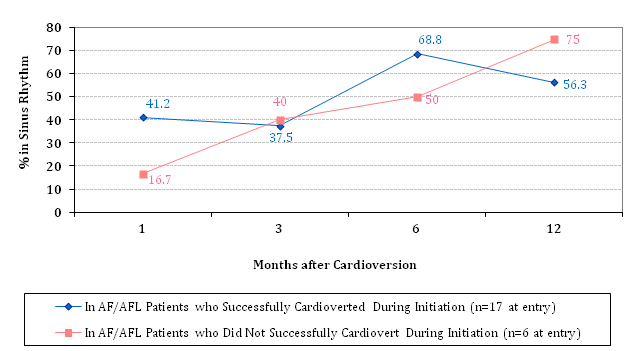

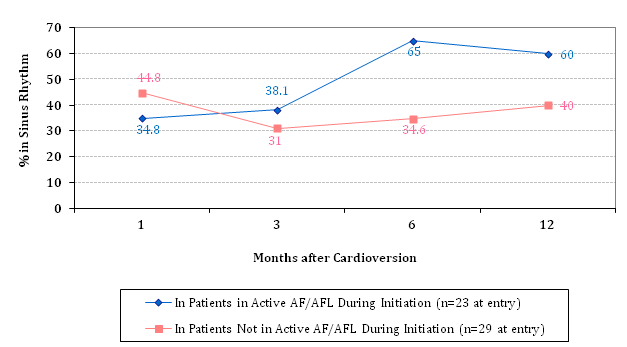

Overall cardio version efficacy with Dofetilide from AF/AFL to SR was 72% (18/25). However, most of this success was due to the combination use of Dofetilide with DCCV, rather than from Dofetilide alone (Table 2A). In these patients who successfully cardioverted during Dofetilide initiation and who remained on Dofetilide during the maintenance phase, maintenance of SR appeared to improve over time, particularly starting at the 3-month time point (Table 2B). This maintenance phase pattern was roughly similar in those who did not successfully convert to SR during Dofetilide initiation, with long-term SR maintenance rates of 40% at 3 months, 50% at 6 months, and 75% at 12 months, all of which were not significantly different from the long-term SR maintenance rates of those who successfully cardioverted during initiation (Figure 1A). Meanwhile, patients who were not in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation appeared to have worse long-term SR maintenance rates, at ~40% at best (Figure 1B).

Endpoint |

DT-VAP(n=25) |

DIAMOND-MI(n=59) |

SAFIRE-D(n=77)† |

Overall Conversion to SR |

18 (72%) |

29 (49.1%) |

62 (80.5%) |

% Converted by Dofetilide alone |

4 (16%) |

25 (42.4%) |

23 (29.9%) |

% Converted by Dofetilide + DCCV |

14 (56%) |

4 (6.8%) |

39 (50.6%) |

Table 2A Efficacy in cardio version of AF/AFL to SR during Dofetilide initiation

†In the 500mcg twice daily arm.

AF: Atrial Fibrillation; AFL: Atrial Flutter; SR: Sinus Rhythm; DT-VAP: Safety and Efficacy of Dofetilide Therapy in a Veterans Affairs Population; DIAMOND-MI: Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide in acute Myocardial Infarction; SAFIRE-D: Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigation and Randomized Evaluation of Dofetilide; DCCV: Direct Current Cardio version

The mean QTC interval at Dofetilide initiation in patients without pacemakers or ICDs was 423 milliseconds (n=22 patients; range 399-439 milliseconds), and 445 milliseconds in those with a pacemaker or ICD in place (n=28 patients; range 386-498 milliseconds). The remaining five patients studied in this trial initiated Dofetilide at an outside hospital before transferring to the Dallas VA Medical Center for their Dofetilide orders and long-term follow-up by the Cardiac Electrophysiology Service. From a mortality standpoint, about one in every 18 patients died during the study, however there were no cases of torsades de pointes. As far as Dofetilide dose adjustments and Dofetilide discontinuations, about one in four to five patients had a Dofetilide dose increase during the study, which is in contrast to zero in the landmark trials (full comparisons in Table 3A). Sixty-seven percent of Dofetilide dose decreases were due to QT prolongation (Table 3B), and treatment failure was the leading reason for Dofetilide discontinuation, although overall incidence of Dofetilide discontinuations still appeared slightly less than those in the DIAMOND studies (Table 3C). About 33% (6/18) of patients with an ICD in place received at least one shock during the study. Three of these patients remained on Dofetilide; 2 switched to amiodarone; and 1 was admitted to an outside hospital and died one month later.

Endpoint |

DT-VAP(n=18) |

DIAMOND-HF (n=190) |

DIAMOND-MI (n=25)‡ |

SAFIRE-D(n=62)† |

SR at 1 month |

7/17 |

12% |

60% |

--- |

SR at 3 months |

6/16 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

SR at 6 months |

11/16 |

--- |

--- |

62% |

SR at 12 months |

9/16 |

44% |

88% |

58% |

Table 2B Efficacy in Maintenance of SR in Those Who Successfully Cardioverted

†In the 500mcg twice daily arm

‡Study only reported maintenance data from AF/AFL patients who successfully converted with dofetilide alone (so n=25); rates were NOT statistically significant when compared to placebo.

SR: Sinus Rhythm; DT-VAP: Safety and Efficacy of Dofetilide Therapy in a Veterans Affairs Population; DIAMOND-HF: Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide in congestive Heart Failure; DIAMOND-MI: Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality ON Dofetilide in acute Myocardial Infarction; SAFIRE-D: Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigation and Randomized Evaluation of Dofetilide; AF: Atrial Fibrillation; AFL: Atrial Flutter

Figure 1A SR Maintenance Rates† in successfully vs. unsuccessfully cardioverted patients

†Differences in SR maintenance rates at each time point were not statistically significant.

Figure 1B SR Maintenance Rates† in Baseline Active AF/AFL vs. Non-AF/AFL Patients.

†Differences in SR maintenance rates at each time point were not statistically significant.

Endpoint |

DT-VAP(n=55) |

Diamond-HF(n=762) |

Diamond-MI(n=749) |

Safire-D(n=241) |

Torsades de Pointes, n(%) |

0 |

25(3.3%) |

7(0.9%) |

2(0.8%) |

Dofetilide Discontinuations |

19(34.5%) |

341(44.8%) |

304(40.6%) |

--- |

Patients with Dofetilide Dose Adjustments |

23(41.8%)† |

--- |

--- |

79(32.8%) |

Dose Decreases |

21(91.3%) |

100% |

100% |

79(100%) |

Dose Increases |

6(26.1%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Mortality at 12months, n(%) |

3(5.5%) |

208(27.3%) |

165(22%) |

6(2.5%) |

Table 3A Safety endpoints

†4 of the 23 patients who had a change in dose had both an increase and decrease or vice versa, so the actual number of dose adjustments was 23+4=27

DT-VAP, safety and efficacy of dofetilide therapy in a veterans affairs population; DIAMOND-HF, danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide in congestive heart failure; DIAMOND-MI, danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide in acute myocardial infarction; SAFIRE-D, symptomatic atrial fibrillation investigation and randomized evaluation of dofetilide

Reasons for dofetilide dose decreases |

DT-VAP(n=21) |

QT prolongation |

14 |

Decreased renal function |

1 |

Decreased AF/AFL burden s/p ablation |

4 |

Unclear/unknown |

2 |

Increases |

DT-VAP(n=6) |

Increased renal function |

1 |

VT storm on ICD |

1 |

Suboptimal starting dose |

1 |

Inappropriate dose reduction(ICD/BiV-paced) |

2 |

Decreased risk of QT prolongation |

1† |

Table 3B Reasons for dofetilide dose adjustments

†Post sotalol discontinuation in the morning prior to the evening dofetilide dose

DT-VAP, safety and efficacy of dofetilide therapy in a veterans affairs population; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; s/p, status post; VT, ventricular tachycardia; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; BiV, biventricular

Reasons for dofetilide discontinuations |

DT-VAP(n=19) |

Diamond-HF(n=341) |

Diamond-MI(n=304) |

Mortality |

3(15.8%) † |

208(61%) |

165(54.3%) |

QT prolongation |

2(10.5%) |

14(4.1%) |

19(6.3%) |

Torsades de Pointes |

0 |

25(7.3%) |

7(2.3%) |

Decreased renal function |

0 |

--- |

--- |

Treatment failure |

6(31.6%) |

--- |

--- |

Ventricular tachycardia |

2(10.5%) |

--- |

--- |

Decreased AF burden s/p ablation |

2(10.5%) |

--- |

--- |

Other |

4(21.1%) ‡ |

--- |

--- |

Table 3C Reasons for dofetilide discontinuations

Causes unclear, however two patients had a recent admission to the hospital for cardiac-related issues prior to death; both died in the outpatient setting. The third death occurred at an outside hospital, where the patient was admitted for worsening shingles that according to the patient’s son started attacking the patient’s nerves

‡Includes post successful orthotopic heart transplant(1), discharge from cardiac EP service(1), patient choice(1), discontinuation at outside hospital(1)

DT-VAP, safety and efficacy of dofetilide therapy in a veterans affairs population; DIAMOND-HF, danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide in congestive heart failure; DIAMOND-MI, danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide in acute myocardial infarction; AF, atrial fibrillation; s/p, status post; EP, electrophysiology

Although efficacy during cardio version with Dofetilide alone was quite low in our study compared to landmark trials, our study may have included patients with more baseline chronic comorbidities and overall health conditions. This was potentially illustrated from the amount of previous ablations or cardio versions our patients received, the amount of patients who attempted a previous antiarrhythmic trial other than Dofetilide, the numerous comorbid health conditions that patients had, the amount of patients who already had an ICD in place prior to starting Dofetilide, and the concomitant medications that patients were on during the study. The obvious caveat to making these direct comparisons with the DIAMOND and SAFIRE-D studies is that the landmark trials did not report and may not have gathered some of the data that we have reported in DT-VAP. However there were points of interest as some clinical characteristics were explicitly excluded by these trials.

The DIAMOND and SAFIRE-D studies both excluded in their patient selection criteria the recent use of a class I or class III antiarrhythmic drug (AAD). Although the DIAMOND trials defined the exclusion of recent use of an AAD as within the previous 3 months before starting Dofetilide, and the SAFIRE-D defined it as use within the previous 6 months, our study could not be as accurate in this department as it was a retrospective chart review, and therefore by nature some patients’ documentation was more complete than others, while others less complete, particularly when some patients may have been treated at outside hospitals before switching to the Dallas VA Medical Center. DT-VAP however did include many patients who were fresh off of another AAD right before Dofetilide initiation. Most of these initiations were secondary to persistent sinus bradycardia caused by sotalol, prompting the switch to Dofetilide which has less beta blocking effects. There was even a case captured in Table 3B where a patient’s theoretical risk of QT prolongation decreased secondary to sotalol discontinuation, with the last sotalol dose in the morning of the evening Dofetilide dose. So where solid, direct comparisons cannot be made, at the same time some inferences can be drawn, hinting that at least some of our patients may not have been able to wait for an entire 3-6 months due to their health conditions before starting Dofetilide.

The DIAMOND studies also excluded in their patient selection criteria the presence of ICDs in patients. This was an immediately easy comparison as it was a during-trial initiation criteria-ICD presence yes or no? Here we can see that 30.9% (17/55) of our study patients had an ICD on board even before starting Dofetilide. That meant about 3 out of every 10 patients in DT-VAP had heart failure or ventricular conduction problems so severe that they already needed an ICD for prevention purposes of sudden cardiac death. Seven of our patients were even administered Dofetilide for ventricular tachycardia suppression, not AF/AFL. None of these patients were studied in the DIAMOND or SAFIRE-D studies. The SAFIRE-D trial neither mentions nor denies the inclusion or exclusion of patients with ICDs.

Other notable differences between DT-VAP and the DIAMOND studies include that the DIAMOND trials actually included patients without ventricular conduction abnormalities who had QTC intervals <460 milliseconds, which is above the FDA and manufacturer’s maximum recommended limit of 440 milliseconds. While this may not have affected the long-term follow-up in those studies, it may have potentially increased their mortality rate as their patients were either within 7 days of suffering from an acute myocardial infarction or within 7 days of developing new-onset or worsening heart failure. It is important to remember that the DIAMOND studies were not intended to investigate cardio version success rate during Dofetilide initiation; they were conducted for the purpose to show or dismiss mortality benefit with Dofetilide. Though their patients’ baseline chronic health conditions appeared relatively few and stable compared to our patients in DT-VAP, the severe acute decompensations in the DIAMOND studies may have led to their higher mortality rates, and also the failed chance to prove any mortality benefit on Dofetilide. The physiology behind acute myocardial infarction and AF/AFL is well-documented but also a controversial AAD target. This revealed itself during the long-term SR maintenance phase of the DIAMOND-MI study as the percentages of SR with Dofetilide was not statistically different from placebo. Therefore, if the DIAMOND-MI’s very high SR maintenance rates were removed from comparison, DT-VAP’s SR maintenance rates actually compared very favorably, nearly identical to those in the SAFIRE-D study, and also appeared to be better than those published in DIAMOND-HF.

What was very fascinating to see from our results was that the chance of staying in SR may not have had to do with anything other than baseline AF/AFL status during Dofetilide initiation. Despite a slight type II error between patients who successfully cardioverted during Dofetilide initiation and those who did not successfully cardiovert, what we saw was a general trend upwards in terms of maintaining SR, starting at the third month after the initiation phase, with a pattern almost mimicking each other as seen in Figure 1A. There was no statistical difference at any time point between the two groups, suggesting a relation that may have aligned with each other much more from a graphing/plotting perspective if we had a larger sample size, such as if this study were designed to include all-comers who started Dofetilide at the Dallas VA Medical Center. What was interesting from this finding however was that it did not matter whether or not the patient successfully cardioverted to SR during Dofetilide initiation-in other words, whether they were successful or not, they had just about an equal amount of chance to maintain SR over long-term follow-up as long as they remained on Dofetilide. When these two groups were combined into a composite to compare patients in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation versus patients not in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation (Figure 1B), what was even more interesting to see was that those not in active AF/AFL when starting Dofetilide appeared to have lower SR maintenance rates all across the board, and this difference manifested starting at the 3-month mark after starting Dofetilide. This suggests that baseline AF/AFL status may actually be an important factor in determining long-term success with Dofetilide as far as maintaining SR. Furthermore, the long-term benefits of Dofetilide appear to reveal itself after 3 months of starting Dofetilide.

From a safety perspective, we believe the reason we saw no cases of torsades de pointes in our study was that it was retrospective in nature, so when these patients were actually being treated in real-time, the clinicians were not aggressively looking for this endpoint like they would in the landmark prospective clinical trials. We do however report that 6 out of 18 patients who had an ICD in place during the study received at least one shock from their defibrillator, and therefore may have had their lives saved. Whether or not these cases were due to torsades de pointes, we cannot be sure as there were no associated EKGs and no further tests that were conducted during the actual time. However, the Dofetilide patients at the Dallas VA Medical Center are closely followed by the Cardiac Electrophysiology Service providers, who manage the patients’ Dofetilide as aggressively as they can without compromising patient safety. This could be illustrated from the fact that we had more Dofetilide dose adjustments compared to the SAFIRE-D trial, even dose increases which are not recommended by the FDA or manufacturer, but that our trial still demonstrated to have slightly less Dofetilide discontinuations overall compared to the published literature from the landmark trials (Table 3A). It is also important to consider that our patients, as mentioned previously, may have had more chronic standing health conditions, requiring expert management that may occasionally require going beyond protocol or manufacturer guidelines. Oftentimes patients had exhausted their other antiarrhythmic options and still have had symptomatic arrhythmias severely impacting their quality of life. These patients had to resort to Dofetilide therapy but safety remained at the top of the Cardiac Electrophysiology Service considerations.

There were several limitations to our study. First and foremost, DT-VAP was retrospective in design. Being that it was retrospectively conducted, data collection was performed as thoroughly as possible but still unavoidably with many missing pieces. Hardcopy EKGs were oftentimes unable to be located. Electronic medical notes were occasionally missing or did not coincide with BCMA records. Sometimes no hardcopy EKG was available at all, particularly if the patient were a medicine floor patient, and all that we could rely on were written QTC intervals in medical notes that may or may not have been determined by an adequately trained clinician. Other times management of Dofetilide slipped through the proper channels, leading to adjustments made by non-Cardiac Electrophysiology Service providers. Furthermore, in cases of differing QTC intervals such as in between medical notes and hardcopy EKGs, we had to try to be as objective as possible by using the hardcopy EKGs for all patients, unless unavailable, knowing that this in itself also presented with limitations as the EKG machine reading can sometimes be wrong. If we used the QTC intervals documented in some medical notes and hardcopy EKGs in others, it would have caused less homogeneity as the EKG results would have come from multiple sources and probably led to a greater degree of error in the end. Also, since our study included patients with pacemakers, it was impossible to determine if a patient with an active pacemaker was in SR or not unless the pacer was turned off for the time being. If unable to determine SR, Dofetilide patients with pacemakers were counted only towards the denominator representing the total number of patients on Dofetilide, but not the numerator representing the number of patients in SR. Theoretically, therefore, our reported rates of successful cardio version and rates of SR maintenance may have been slightly higher if all patients’ pacemakers were turned off during the time of EKG reading, because their intrinsic rhythm may have been in sinus although we will never know.

Although the aforementioned limitations were all weaknesses to our study, at the same time one could argue that altogether these also become strength, given that DT-VAP was conducted as close to a real-life, real world scenario as one could get. The practice of medicine, at best, follows evidence-based medicine and practice-based guidelines, but where these resources are limiting to real-life patients, clinical judgment, innovation, and sometimes even a bit of chance come into play. We feel that DT-VAP was able to capture Dofetilide use in the Veterans Affairs population at a single VA Medical Center to the realist extent possible, because in real-life it is impossible to control for everything like in prospective clinical trials. Overall, despite sample size, we feel our data was very robust and we are impressed with the results.

Dofetilide use is safe and effective in the Veterans Affairs population both during initiation and long-term follow-up. Baseline AF/AFL status however may be an indicator in determining long-term success with Dofetilide, as patients not in active AF/AFL during Dofetilide initiation tended to have lower SR maintenance rates than those in active AF/AFL during initiation. Long-term efficacy with Dofetilide appeared to manifest three months into using Dofetilide. The majority of our Dofetilide dose reductions were due to QT prolongation.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Chen, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.