eISSN: 2379-6367

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 6

1University of Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo

2Maisons de l'Artemisia, Paris

3CAE, Lubumbashi, Congo

4IFBV-BELHERB, Luxembourg

Correspondence: Pierre Lutgen, IFBV-BELHERB, BP 98 L-6905, Niederanven, Luxembourg

Received: October 30, 2018 | Published: December 4, 2018

Citation: Munyangi J, Cornet-Vernet L, Tchandema C, et al. Deleterious effects of Artemisia infusions on Paramecium, Vibrio and Plasmodium. Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2018;6(6):462-466. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2018.06.00219

Paramecium is an alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites (Plasmodium, Toxoplasma). As in vivo trials with antimalarial drugs are difficult to perform, mostly for ethical reasons, and as in vitro trials may be meaningless because the protozon Plasmodium, which needs a specific culture medium which interfers itself with the antimalarial drug, may react in a completely different way in vivo, where antimalarial drugs are dismantled by metabolism. Cultures of Paramecium tetraurelia are easy to cultivate and to handle. In vitro trials were run in 2014-2015 at the Laboratoire de Biologie cellulaire et moléculaire de l’Université Paris 11 with infusions of Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra and showed several detrimental effects on the behaviour of this parasite. This confirms similar effects on Vibrio fischeri and Vibrio cholerae which had been identified earlier.

Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra

The in vivo effects of Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra on Plasmodium falciparum have been documented in scientific publications since 2005 in Kenya, Cameroon, Mozambique, Uganda, Togo, Senegal, Ethiopia, Mali, Benin and RDCongo.1‒13 In this most recent clinical trial a team of medical doctors in RDCongo, J. Munyangi and M. Idumbo, have run randomized clinical trials on a large scale in the Maniema province with the participation of some 1000 malaria infected patients. The trials were run in conformity with the WHO procedures and compared Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra with ACTs (Coartem and ASAQ). For all the parameters tested herbal treatment was significantly better than ACTs: faster clearance for fever and parasitemia, absence of parasites on day 28 for 99.5% of the Artemisia treatments and 79.5% only for the ACT treatments. A total absence of side effects was evident for the treatments with the plants, but for the 498 patients treated with ACTs, 210 suffered from diarrhea, and/or nausea, pruritus, hypoglycemia etc. The efficiency was equivalent for Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra. More important even is the observation for the total absence of gametocytes after 7 and 28 days treatment with the herb. The effects of Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra on other parasites, helminths and micobacteria has also been studied in vivo by our research group. Against all these diseases it shows a surprising activity and efficacy.

Paramecia tetraurelia

Paramecia is an unicellular eukariot. It is easily cultivated in the laboratory, its observation under the microscope is evident (120μm large) and permits to follow the cellular cycle, the behaviour, the morphogenesis, its secretions and a large set of other biological functions. Its autogamy produces 100% homozygotic clones where toxicological impacts are easy to follow. It has the elongated form of a slipper (Pantoffeltierchen in German with a dorsal-ventral polarity. The dorsal side carries two pulsatile vacuoles which also control osmolarity. The oral aperture is on the bottom side and allows to swallow bacteria. Metabolic waste is expulsed by the anal cytoprocte. A very specific feature of Paramecium are thousands of cilia on its surface which contribute to great motility and allow forward and backward swimming. At the encounter of an obstacle Paramecium will retreat brusquely. Cilia also serve as antennae for chemical signals (attraction and repulsion).14‒16

This ciliated protozoan can alter its swimming behaviour in response to a change in the ionic concentration of the environment. Calcium serves as a messenger in all eukaryotes, from man to protozoa, including ciliates. Ca²⁺ may govern widely different processes, including cell movements, cytokinesis, morphogenesis. Cells dispose not only of Ca²⁺ influx channels, but also of intracellular release channels. It is likely that the Artemisia infusions act on the SERCA channels of Paramecium, but we do not know by which constituent. In this ciliated protozoan alveolar sacs underlie the somatic cell membrane. These sacs are targets of Ca⁺² stimulation.17,18 Inhibitors of SERCA (sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺ dependent ATPase) calcium pumps have an impact on internal Ca²⁺ stores in Paramecium. External application of inhibitors may dramatically alter the typical behavioral and electrophysiological responses of Paramecium to extracellular chemical stimulation.19

The influence of potassium on calcium has been studied more extensively in the case of Toxoplasma gondii, another apicomplexan. The reduction of extraparasitic K⁺ and calcium fluxes within the parasite are known to activate the parasite’s motility machinery. For instance, buffers containing K⁺ levels that mimic the high concentration normally found within host cells block the motility of extracellular parasites. Similarly, intraparasitic calcium fluxes activate and regulate motility related events.20,21 When the K⁺ concentration of the surrounding medium is lowered, the cells initiatially accelerate forward swimming. However, when they are transferred to a solution of higher K+ concentration, they show transient backward swimming and then recover.22,23 Artemisia plants are very rich in potassium and basically don’t contain any sodium.24

Paramecium has a mitochondrion. It has been shown that silica nanoparticles induce an oxidative stress which could play an important role of the mitochondrial membrane damage and the cell apoptosis. Artemisia plants are rich in silica nanoparticles.25‒27 Paramecium has been used to evaluate sludge toxicity, pyrethroid toxicity, Paramat toxicity. Many bioassays for herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, antimicrobials, heavy metals are based on Paramecium.28 Nickel is known as one of the most effective immobilization agents for protozoa. It was found to have a high toxicity on Paramecium bursaria. At concentrations of 5x10-²g/dm3 it completely immobilizes the cells, stops rotary movement and leads to deformation and death. In humans, it accumulates to a large extent in the liver.29‒32 The solubility of nickel from medicinal plants in aqueous infusions is higher than that of other metals and it has been estimated that the daily intake of Ni⁺⁺ from infusions of medicinal herbs is 4-5 times higher than from tap drinking water.33

Many Asteraceae plants are known as hyperaccumulators of heavy metals and Artemisia plants are part of this familiy. They are even used for bioremediation of contaminated soils.34,35 A detailed study on the influence of tin oxide SnO₂ nanoparticles on Paramecia tetraurelia was made in Algeria. An increase in the number of Paramecium at low concentrations of SnO₂ and its inhibition at high concentrations was noticed. An obvious effect of hormesis: low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition.36 The antimalarial drugs, quinacrine, quinine and mefloquine induce calcium-dependent backward swimming in Paramecium calkinsi. These drugs are also toxic to Paramecia at high concentrations. Therefore, one site of toxic action of the drugs may be the calcium channel. This is definitely the case for pyrethroids.37,38 The Alveolates (Paramecium, Tetrahymena) are close relatives of the Apicomplexa (Plasmodium, Toxoplasma). The toxic effects of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin on the growth metabolism of Tetrahymena thermophila were studied by microcalorimetry. The results showed that: low concentrations of artesunate (<or=1mg L-1) and dihydroartemisinin (<or=2mg L-1) promoted the growth metabolism of T. thermophila , whereas high concentrations of artesunate (1-60 mg L-1) and dihydroartemisinin (2-60 mg L-1) inhibited its growth.39

Preparation of Artemisia infusions

A mixture of Artemisia leaves and twigs (Artemisia annua or Artemisa afra) was used in powder form. 2g are weighted on a precision electronic scale, placed in a tube and a litre of boiling demineralized water at 100°C is added. pH of the cold infusion was measured routinely and is between 7.0–7.8 for the different media used in the Paramecium test. The original infusion was used at different dilutions. For the trials we used progressive dilutions: 100, 50, 20, 10, 0 mg/L

Preparation of the Paramecia tetraurelia culture

The techniques used for the culture of Paramecium are those described by Sonneborn revised by Janine Beisson.40,41 Paramecium tetraurelia feeds on bacteria and develops best at 27°C with 4 to 5 divisions per day. The culture medium was BHB: an infusion of wheat grass, containing 50μM of calcium and 0.4µM of Na⁺ and the day before its use Klebsiella pneumoniae were added. A fresh culture is established every 3 days in order to use Paramecium during its exponential growth phase. We prepared infusions with 2, 4, 6, 8 g/L of Artemisia powdered leaves and added them to the culture, before adding the Paramecia

Measurement of growth kinetics

The growth kinetics of Paramecia vs time were established by counting them under the microscope (Leica DL 1000) following the procedure of Bouaricha at a 10x enlargment. The cell number is counted immediately after addition of the Artemisia infusion, and than after one hour and after 72 hours. For some measures we also used a binocular magnifier Nikon with continuous zoom. A camera (CCD 2048*2048px) is mounted on this magnifier allowing video recording.42

Percentage of response

Percentage of response is a parameter used to evaluate the xenobiotic effect of Artemisia via the inhibition of cell growth of protists. Percentage of response is calculated by the formula

Response (%)=(CN-EN)/CNx100

where CN is the number of control cells and EN the number of treated cells. Positive values of response Percentage indicate an inhibition of growth, while negative values indicate a stimulation of growth

Mortality rate

Mortality rate is established by counting the cells up to 72 hours.

Malformation rate

Malformations are detected by observations under the microscope at an enlargment of 100 following the procedure of Azouz. Malformations include changes in scape, loss of cilia, budding and sprouting on the membrane.43

Modification in the endocytose and exocytose functions

These modifications are evaluated after the addition of picric acid and are based on the number of digestive vacuoles. The observations are made by placing the Paramecia between slides and plates under the microscope (Leica DL 1000) at an enlargment of 10.

Study of the calcium receptors

Was based on the SERCA inhibition.

Previous results showing the effect of Artemisia infusions on Vibrio fischeri and Vibrio cholerae

In 2008 IFBV-BELHERB had run some experiments with Artemisia annua infusions on Vibrio fischeri. Infusions were prepared by adding a liter of boiling tap water to 5 g of the dry Artemisia annua herb and leaving to infuse for 10 minutes before filtering (Figure 1). This effect on Vibrio was later confirmed by the University des Montagnes in Cameroun. Among 8 bacterial strains tested Vibrio cholerae showed the greatest antibacterial sensitivity to Artemisia annua essentiel oil.44 In 2009 IFBV-BELHERB had used Paramecium to study the influence of UV radiation and Artemisia annua infusions on the sterilization of waste water (report Pollutec Paris dec 2009).

Dose-effect relationship on swimming behaviour.

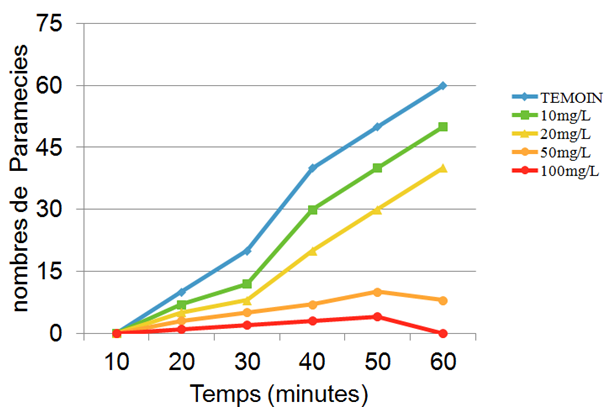

This parameter is studied by comparing controls with Paramecia treated with different doses of Artemisia infusion. Figure 2 describes the swimming behaviour at different doses. For the control Paramecia we notice an increase starting after 10 minutes and reaching a plateau after 50 to 60 minutes. At the beginning Paramecia treated with Artemisia infusion behave in the same way, but rapidly a dose dependent inhibition is noticeable. At a concentration of 100mg/L the movement is completely inhibited. At low concentrations of 20 mg/L the swimming speed was reduced and sometimes backward swimming was noticed.

Figure 2 Effect of increasing concentrations of Artemisia infusions on the swimming behaviour of Paramecia.

Observation of immobilized Paramecia

This observation was done under the microscope at an enlargement of 40 on plates having small cavities. These immobilized Paramecia are still alive. Some have lost their cilia. Pictures with further enlargements were obtained with the binocular lens, a Basler camera coupled with an USB 3.0 computer

Study of exocytosis

This was done by comparing Paramecia treated and immobilized by Artemisia infusions with those immobilized by picric acid. In Paramecia tetraurelia, a crucial step in the secretory process is the transport of secretory organelles to the cell surface, before exocytosis can occur. It has been postulated that micro-tubules might represent long-range signals or guiding rails for secreta transport. An enhanced Ca²⁺ to the attack of xenobiotics may trigger this excretion process. We could not observe this feature in Artemisia treated parasites although their cellular membrane was inflated. In the control Paramecia, some excreta could be observed around the buccal cavity.

Comparing the effect of the two Artemisia species used: annua and afra.

For growth rate the comparisons are always made during the exponential growth phase of the parasites. For Artemisia annua we were not able to notice a difference in the behaviour of the cells treated by the infusion and the control cells at the early stages of the treatment. Only after one hour do we notice a difference in the growth rate and the inhibition steadily increases, and is dose dependent. After 48 hours growth inhibition is complete. For Artemisia afra we notice an immediate decrease in the Paramecia count which progressively becomes more severe for higher doses. Percentage of response was established according to the procedure of Wong.45 For both plants we notice a dose dependence. For Artemisia annua we find 38.26% at 2g/L for the reponse percentage and 88.26% at 8g/L. For Artemisia afra it is 11.0% at 2g/L and 90.3% at 8/gL.

Mortality rate

For Artemisia annua the mortality rate is of 4.2% after 1 one hour treatment at 6g/L. After 72 hours of the 6g/L treatment it reaches 16.35%. For Artemisia afra we notice a mortality rate of 4.15% after 72 hours of exposure to 6g/L. At the dose of 8g/L we notice 16.35%.

Morphological changes and malformations

The control Paramecia keep their elongated shape and a regular trajectory. Those treated by both Artemisia infusions see a significant and dose dependant increase of invaginations.

Evolution of number of digestive vacuoles

The Artemisia infusion treatments lead to a significant diminution in the number of digestive vacuoles when compared to controls. Controls carry between 7 to 10 vacuoles. For Artemisia annua at a dose of 4g/L we only find 4 vacuoles an at 4 g/L and this number goes down to 2 at 8g/L. For Artemisia afra we also notice a 80% diminution at the dose of 8g/L.

SERCA receptors

A dose dependent decrease of SERCA receptors was noticed for Paramecia treated by Artemisia infusions.

All the parameters we have studied show a deleterious effect of Artemisia infusions on Paramecia tetraurelia. Similar effects were found for other Apicomplexa. The ease of Paramecia culture and handling justifies further studies on the effect of Artemisia plants. The eukaryote Paramecium carries a nucleus, a mitochondria and a cytoskeleton. The impact of toxic substances on Paramecia could thus be extrapolated to pluricellular organisms. It is also worth while to consider the hypothesis that the effect Artemisia has on the motility of Paramecium may also play a role in the gliding behaviour of Plasmodium sporozoites, and consequently the invasion of hepatocytes.

The work of Jerome Munyangi shows that the effects of Artemisia annua and Artemisia afra are similar. Artemisia afra does not contain artemisinin. Artemisia afra is an indigenous plant of Africa. WHO/EDM/TRM/2000.1 stipulates that if documentary evidence shows that a plant has been used over three or more generations for a specific health related purpose, there is no requirement for pre-clinical toxicity testing. It remains to be assessed if either the prooxidant organic constituants of Artemisia or the minerals it contains are responsible for the detrimental effects on Paramecium.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

©2018 Munyangi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.