eISSN: 2379-6367

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 4

1Central Public Health Laboratory, Ministry of Health, Ramallah, Palestine

2Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Quds University, P. O. Box 20002, Abu- Dies, Palestine

Correspondence: Saleh Abu-Lafi, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Quds University, Abu-Dies, Palestine, Tel ++972-2-2799360

Received: July 04, 2025 | Published: July 30, 2025

Citation: Jahajha A, Abu-Lafi S. Comparative evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Calamintha incana essential oil. Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2025;13(4):127-132. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2025.13.00476

Calamintha incana (C. incana), a wild aromatic plant native to the Mediterranean region, was investigated for its antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The plant essential oil was extracted via steam distillation (SD) and chemically characterized in our previous studies using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). In this work, its antioxidant activity was evaluated using the 2,2'-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay and compared to the standard antioxidant, Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT). The results showed that the oil exhibited moderate free radical scavenging activity that increased with time and concentration but remained lower than BHT, likely due to its lower phenolic content. The antimicrobial potential of the oil was assessed using the disc diffusion method against a range of microorganisms, including Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Candida albicans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The oil demonstrated strong activity, outperforming gentamicin against Escherichia coli and Salmonella, and exceeding the effectiveness of nystatin against both fungi. However, it showed no activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis. The oil’s antimicrobial effects are probably attributed to bioactive compounds present in the oil such as pulegone and carvone.

Keywords: Calamintha incana, essential oils, antioxidant activity, antimicrobial activity, DPPH assay, gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria

C. incana, Calamintha incana; SD, steam distillation; GC-MS, gas chromatography–mass Spectrometry; DPPH, 2,2'-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; BHT, butylated hydroxytoluene; UV-Vis, ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer; NaCl, sodium chloride; CFU, colony forming unit; ATCC, American type culture collection; E. coli, Escherichia coli; IU, international unit; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; ROS, reactive oxygen species

Calamintha incana (family: Lamiaceae) is an aromatic medicinal plant traditionally used in Mediterranean herbal practices for its calming, digestive, and antimicrobial properties. As with many species in the Calamintha genus, C. incana is rich in bioactive compounds such as flavonoids and essential oils, many of which have been linked to potent pharmacological activities.1–5

Antimicrobial resistance is an escalating global threat, reducing the efficacy of conventional antibiotics and creating an urgent need for novel, natural alternatives.6,7 At the same time, concerns about the safety of synthetic antioxidants have fueled interest in natural compounds capable of neutralizing free radicals and reducing oxidative stress-processes implicated in the onset of chronic diseases like cancer, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular conditions.8–10 In this context, essential oils from aromatic plants are increasingly investigated for their dual role as natural preservatives and therapeutic agents, thanks to their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.11,12

Despite this global interest, the biological properties of C. incana-particularly from Palestine-have remained largely unexamined. In response to this gap, our research group recently initiated a series of studies to characterize and evaluate the bioactivity of C. incana growing wild in Palestine. In the first of these investigations, we determined the chemical composition of the plant’s essential oil using Steam Distillation-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (SD-GCMS), and observed variation in the presence of key monoterpenes such as pulegone, menthone, and isomenthone based on geographical origin.13 Following this, we assessed the metal content of the plant leaves to explore both their environmental implications and safety for use.14

Our work complements findings from other parts of the region. In Turkey, for example, the essential oil of C. incana was shown to possess antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.4 Similarly, a study from Jordan evaluated the methanolic extract of C. incana, identifying phenolic compounds responsible for significant antibacterial and free radical-scavenging activity.5 While these studies highlight the plant’s potential, none have comprehensively investigated the essential oil of C. incana from Palestine in terms of both its antioxidant and broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties.

The aim of this research is to evaluate the antioxidant activity of C. incana essential oil using spectrophotometric methods. Moreover, it seeks to determine the oil's antimicrobial activity against a range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as selected fungal strains, and to compare its effectiveness with that of standard antimicrobial agents.

Material and instruments

The following chemicals and reagents were used in this study: methanol, 2,2'-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), and tert-butyl-4-hydroxy toluene (BHT), all sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Microbiological media included nutrient agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco), with the latter used specifically for Candida albicans. Additional reagents such as purified water, 0.9% sodium chloride (analytical grade), ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, nystatin (used as antimicrobial standards), barium chloride, and sulfuric acid (both AR grade) were provided by the Central Public Health Laboratory, Ministry of Health, Ramallah, Palestine. The microbial strains used in the antimicrobial assays were obtained from Becton Dickinson (France) and included:

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923)

Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 12228)

Escherichia coli (ATCC 8739)

Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC 14028)

Candida albicans (ATCC 10231)

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ATCC 9763)

Instrumentation included a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Lambda 25, Perkin Elmer, USA), an analytical balance (Sartorius, Germany; accuracy ±0.0001 g), an incubator (B-series BD15, Binder, Germany), and an autoclave (Model 3870e, Tuttnauer, USA).

Preparation of essential of wild C. incana

Essential oil was extracted from wild C. incana leaves via steam distillation using a Clevenger-type apparatus. Approximately 10 g of finely ground leaves were mixed with 300 mL of distilled water and distilled for 3 hours. The aqueous distillate was then extracted twice with 100 mL of hexane using a separatory funnel. The combined hexane layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. An aliquot of 500 µL from the hexane extract was diluted to 1 mL with hexane for GC-MS analysis; 1 µL of this mixture was injected into the instrument under optimized conditions. The remaining hexane extract was evaporated under vacuum using a rotary evaporator. The obtained essential oil was stored in sealed amber vials at low temperature for subsequent antioxidant and antimicrobial evaluations.

Assessment of the anti-oxidant activity

The antioxidant capacity of C. incana essential oil was evaluated using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay. The method is based on the discoloration of a purple methanolic DPPH solution upon reduction by antioxidant compounds, which is measured spectrophotometrically at 517 nm.

Various concentrations of the essential oil were prepared in methanol. From each dilution, 50 µL was added to 2 mL of DPPH solution (6 × 10⁻⁵ M). The mixtures were wrapped in aluminum foil to protect from light and incubated in the dark. Absorbance was recorded at three time points: 30, 60, and 90 minutes.

BHT was used as a reference antioxidant control. A dilution series of BHT was prepared, and 5 µL from each was mixed with 2 mL of DPPH solution, yielding final concentrations ranging from 0.015 to 0.125 mg/mL. The radical scavenging activity was calculated using the following equation:

% DPPH radical scavenging activity (AI %) = [1- (As/Ac)] x 100

Where:

AI% = Antioxidant Index

Aₛ = Absorbance of the sample

A𝑐 = Absorbance of the control

Methanol was used as the blank. The resulting data were plotted to determine the IC₅₀ (concentration at which 50% of DPPH radicals are scavenged).

Preparation of microbial suspensions

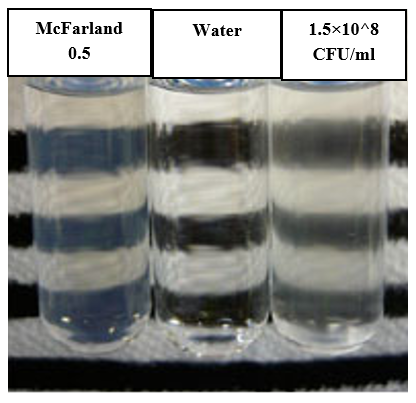

Each strain was suspended in a 0.9% NaCl solution until it reached 0.5 McFarland standards. This was achieved by measuring transmittance using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. McFarland standards were used to standardize the approximate number of microbes in the liquid suspension by visually comparing the turbidity of microbial suspension with the turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standard as in Figure 1 and was prepared as follows: 85 ml of 1% (v/v) sulfuric acid was added into a 100 volumetric flask. 0.5 ml of 1.175% barium chloride solution was added drop wisely to the above flask with continuous swirling and stirring. The volume was completed to 100 ml by 1% (v/v) sulfuric acid. The optical density (amount of light scattered by bacteria) was measured at 625nm and should be in the range (0.08-0.1).

Figure 1 Visual comparison of microbial suspension turbidity with the 0.5 McFarland standard, using a Wickerham card as a contrasting background to ensure accurate matching.

Media preparation

One liter of nutrient agar (Difco) and sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco) was prepared in water, dissolved, boiled and sterilized at 121°C for 20 min. 20 ml of agar was added to each plate. 0.1 ml of microbial NaCl suspensions was diluted with NaCl to 10 ml then 0.1 ml of the new suspension was spread with glass rod on the surface of the agar plate by streaking. The final concentration of both bacteria and fungi on each plate was about 1.5 x 106 CFU/ ml.

Positive control preparation and antimicrobial testing

Solutions of gentamicin (10µg/ml), ciprofloxacin (10µg/ml) and nystatin (115 IU/ml) were prepared and used as positive control.

The test was carried out using disk diffusion method. Four disks were spread on the surface of the media in each plate. 5 µl of sample (C. incana oil)/positive control was added to each disk. Each plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 hr for bacteria while for Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae it was incubated at 25 °C for 72 hr. Negative control for each plate type was performed by following the same procedure. The zone of inhibition was measured by calibrated digital caliber and the result was documented.

Antioxidant activity of C. incana essential oil

Antioxidants play a crucial role in both the medical and food industries due to their ability to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are known to cause oxidative stress. Oxidative damage has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic diseases, including liver disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular conditions. In recent years, considerable interest has been directed toward natural antioxidants derived from plants and food sources.

The antioxidant capacity of C. incana essential oil was evaluated using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay. Various concentrations of the essential oil were prepared in methanol, ranging from 0.122 to 1.35 mg/mL. For each concentration, 50 µL of the oil solution was added to 2 mL of a methanolic DPPH solution (6 × 10⁻⁵ M). Samples were protected from light by wrapping in aluminum foil and incubated in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm after three time intervals: 30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 90 minutes. As a positive control, tert-butyl-4-hydroxy toluene (BHT) was tested in parallel under identical conditions. A series of BHT concentrations (0.015 to 0.125 mg/mL) was prepared, and 5 µL from each was mixed with 2 mL of DPPH solution. The antioxidant index (AI%), reflecting the DPPH radical scavenging activity, was calculated using the following formula:

(AI %), %DPPH radical scavenging activity = [1- (As/Ac)] x100

Where:

Aₛ is the absorbance of the sample

A𝑐 is the absorbance of the control

The AI% values were plotted against the respective concentrations to determine the antioxidant efficiency of both oil sample and BHT.

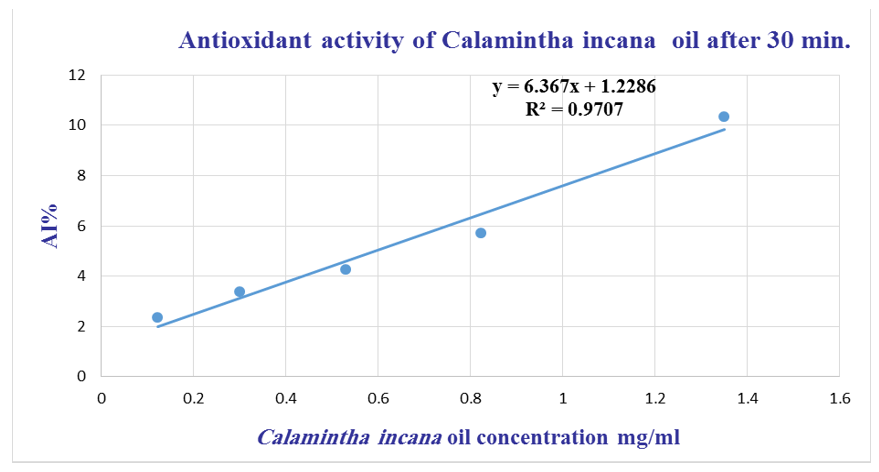

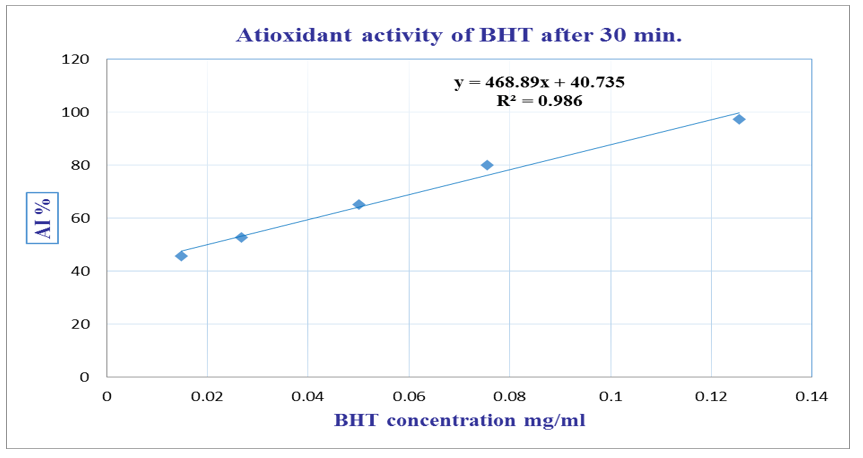

Figure 2 illustrates the antioxidant activity of C. incana essential oil after 30 minutes of incubation, while Figure 3 displays the antioxidant performance of BHT under the same conditions.

Figure 2 Antioxidant activity of C. incana essential oil measured by DPPH radical scavenging assay after 30 minutes.

Figure 3 Antioxidant activity of the positive control (BHT) measured by DPPH radical scavenging assay after 30 minutes.

Antioxidant activity after 30 minutes

The antioxidant activity of C. incana essential oil after 30 minutes of reaction time is illustrated in Figure 2, showing the dose-dependent radical scavenging effect. For comparison, the antioxidant activity of the standard compound BHT under identical conditions is presented in Figure 3. Both curves demonstrate the ability of the test substances to scavenge DPPH free radicals, with activity increasing proportionally with concentration.

From the data presented in Figures 2 & 3, a linear relationship was observed between concentration and antioxidant activity for both C. incana essential oil and the positive control (BHT). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) was determined to be 7.66 mg/mL for the essential oil and 0.02 mg/mL for BHT. These results indicate that while the essential oil exhibits antioxidant activity, it is significantly less potent than the synthetic antioxidant BHT positive control.

Antioxidant activity after 60 minutes

The antioxidant activity of C. incana essential oil after 60 minutes of incubation is shown in Figure 4, demonstrating its free radical scavenging capacity over time. For comparison, the antioxidant activity of the positive control, BHT, under the same conditions is presented in Figure 5.

The IC₅₀ values calculated after 60 minutes of incubation were 7.019 mg/mL for C. incana essential oil and 0.004 mg/mL for BHT. These results indicate that, although the antioxidant activity of the oil improved slightly over time, it remains considerably lower than that of the positive control.

Antioxidant activity after 90 minutes

The antioxidant activity of the oil after 90 min. is illustrated in Figure 6.

IC50 for C. incana oil was 4.767 mg/ml, while it was excluded for BHT because of un- harmonized values. IC50 values for both sample and positive control were represented in the following histogram in Figure 7.

The histogram above clearly demonstrates that C. incana essential oil exhibits antioxidant activity, although it is considerably lower than that of the positive control. Within the tested concentration range, the free radical scavenging capacity of the oil increased in a concentration-dependent manner. Specifically, DPPH scavenging activity (%) rose significantly as the concentration of C. incana essential oil increased from 0.122 to 1.35 mg/mL. Furthermore, the antioxidant activity improved over time, indicating that sufficient incubation time is necessary to achieve optimal scavenging effects.

This antioxidant activity is primarily attributed to the major bioactive components of the oil, such as oxygenated compounds and Terpenes. Preliminary GC-MS analyses confirmed the presence of these compounds, which are well-known for their free radical scavenging properties.15,16

There is growing interest in identifying natural antioxidants to replace synthetic ones, particularly in the food and cosmetic industries. Synthetic antioxidants like BHT and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) have been extensively studied for safety concerns, revealing that prolonged exposure may cause thyroid, liver, and kidney dysfunctions. Additionally, high doses of BHT have been suggested to mimic estrogen, potentially disrupting reproductive system functions.17,18

Antimicrobial activity

In the present study, an initial screening of the antimicrobial activity of C. incana essential oil was conducted against various microorganisms. The antimicrobial effects of 5 µL of the essential oil were tested on Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis), Gram-negative bacteria (Salmonella typhimurium, Escherichia coli), and fungi (Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae), alongside positive controls (gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and nystatin) using the disc diffusion method. The resulting zones of inhibition, illustrated in Figure 8, were measured, and the average diameters are summarized in Tables 1 & 2.

|

Zone of inhibition (Average ± SD) mm |

||||

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

Salmonella typhimurium |

Staphylococcus epidermis |

Escherichia Coli |

|

|

C. incana oil (5 µl) |

10.74 ±1.10 |

18.57±1.68 |

N.S |

16.13±1.39 |

|

Gentamicin 10 µg/ml |

8.7±0.49 |

9.84± 0.66 |

12.36±0.32 |

9.81± 0.73 |

|

Ciprofloxacin 10 µg/ml |

N.T |

21.73± 0.51 |

N.S |

24.11±0.54 |

|

Blank |

N.S |

N.S |

N.S |

N.S |

Table 1 Antimicrobial activity of C. incana essential oil and positive controls against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, presented as average inhibition zone diameters (mm).

N.S: Not Sensitive

N.T: Not tested

|

Zone of inhibition (Average ± SD) mm |

||

|

Candida Albicans |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|

|

C. incana oil (5 µl) |

15.86±0.59 |

18.94 ±1.10 |

|

Nystatin 115 IU/ml |

6.78 ±0.19 |

6.96 ± 0.29 |

|

Blank |

N.S |

N.S |

Table 2 Antifungal activity of C. incana essential oil and positive control (nystatin) against Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, expressed as average inhibition zone diameters (mm).

N.S: Not Sensitive

A comparative overview of the antimicrobial activities of C. incana essential oil against the tested microorganisms is illustrated in Figure 9.

The results revealed that C. incana essential oil exhibited strong antibacterial activity against most of the tested fungi and bacteria. Both groups showed sensitivity, with 5 µL of the oil demonstrating notable antimicrobial effects against certain Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium). Remarkably, the activity of the oil at this volume was superior to gentamicin against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella typhimurium. Moreover, this quantity of C. incana oil was approximately three times more effective than nystatin against Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Conversely, the oil showed no inhibitory effect against Staphylococcus epidermidis. Although ciprofloxacin exhibited greater antimicrobial activity than 5 µL of the essential oil against the tested organisms, the toxicity associated with gentamicin restricts its clinical use.19,20 Similarly, nystatin resistance has been reported following gradual exposure, with several Candida isolates becoming resistant.21

The antifungal activity of C. incana essential oil is primarily attributed to its antimicrobial constituents, which disrupt fungal cells by altering mucous membrane structure and moisture, interfering with respiratory processes, and ultimately eliminating the pathogen.22 The antimicrobial mechanisms of essential oils are multifaceted but may largely be due to their hydrophobic nature, which enables them to partition into the lipid bilayers of bacterial cell membranes and mitochondria. This disrupts cell integrity, increases permeability, and causes leakage of vital molecules and ions, leading to cell death.16

The antimicrobial activity of C. incana oil has been linked to key constituents such as the Menthone, Pipertone oxide and Pulegone. Thus, the overall therapeutic effect of C. incana oil could be attributed to the synergistic interactions of individual components and to the anti-inflammatory approved effect of this oil which can lead to easier passage of the essential oils through mucous membrane. Initial screening of oil's activity revealed that this oil might be active against both bacteria and fungus which might be superior to the available antibiotics which usually act on one type only. Further studies are needed to estimate the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the safety of this oil.

The antioxidant activity results showed that the essential oil’s activity was lower than that of the positive control (BHT) but increased over time. This reduced antioxidant capacity may be attributed to the relatively low phenolic content in C. incana.

Antimicrobial testing demonstrated that the essential oil is effective against both bacteria and fungi. Specifically, 5 µL of the oil exhibited significant antimicrobial activity against certain Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli and Salmonella). The oil’s activity was comparable to gentamicin against Staphylococcus aureus and nearly twice as effective as gentamicin against Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Additionally, the oil was three times more effective than nystatin against Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These promising results are especially important given the rising resistance to existing antimicrobial agents and their known toxicities. These findings are consistent with studies from Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, where similar bioactivities of C. incana extracts were reported. This cross-regional validation strengthens the evidence for its potential therapeutic value

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2025 Jahajha, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.