eISSN: 2379-6367

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 5

1Macedonian Agency for Medicines and Medical devices, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia

2Institute of preclinical and clinical pharmacology with toxicology, Faculty of Medicine, University St. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia

3Institute of epidemiology and biostatistics with medical informatics, Faculty of Medicine, University St. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia

4Zan Mitrev Clinic, Clinical Hospital, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia

5Faculty of Medical Sciences, Goce Delcev University, Shtip, Republic of North Macedonia

6Bionika Pharmaceuticals, Republic of North Macedonia

Correspondence: Iskra Pechijareva Sadikarijo, Macedonian Agency for Medicines and Medical devices, St. Cyril and Methodius 54, 1000 Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia, Tel 0038975430177

Received: August 25, 2025 | Published: September 18, 2025

Citation: Sadikarijo IP, Petrovski O, Lazarevska L, et al. Assessing knowledge of the pharmacovigilance system and the contribution of continuing medical education among medical students and active stakeholders. Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2025;13(5):155-161. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2025.13.00479

Post-marketing surveillance requires the establishment of a system to monitor drug effects in real-world practice, including the collection and analysis of safety data after marketing authorization, known as pharmacovigilance (PV). Healthcare professionals are key elements in PV, as they are directly involved in prescribing, dispensing, and monitoring drug therapy. Their knowledge, clinical experience, and direct access to patients are crucial for the timely detection, assessment, and minimization of risks related to drug use.

Objectives: The main objective of our study is to assess the knowledge and attitudes regarding the PV system among active stakeholders - healthcare professionals (medical doctors, pharmacists, and nurses/medical technicians employed in various positions) and medical students.

Materials and methods: The research was designed as a descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study with MCQ test prepared for assessing the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals and third-year medical students regarding the PV system.

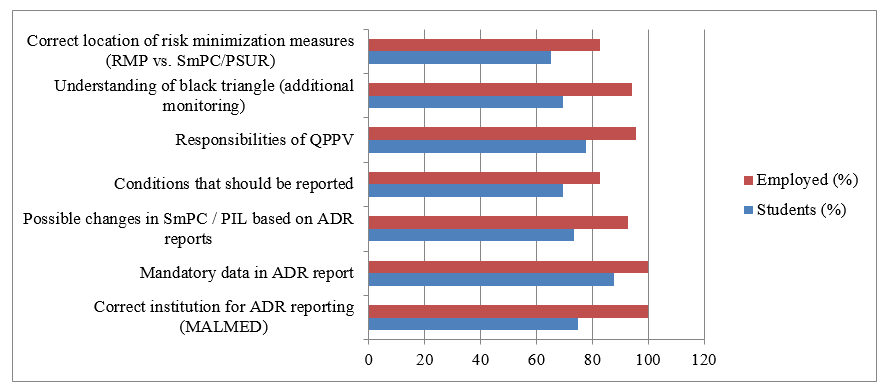

Results: According to this study, employed participants were better informed about the PV system and highly noligable on reporting of adverse reactions, mandatory data in the report as well possible changes in the SmPC and PIL based on reported adverse reactions, and the duties and responsibilities of the QPPV Students demonstrated statistically significantly lower knowledge compared to employed participants, particularly regarding where adverse reactions are reported (75% vs. 100%, p=0.000072), mandatory data in the report (87.76% vs. 100%, p=0.002661), possible changes in SmPC and PIL (73.47% vs. 92.86%, p=0.000381), conditions to report (69.39% vs. 82.86%, p=0.017804), responsibilities of the QPPV (77.55% vs. 95.71%, p=0.016367), and where risk minimization measures are described (65.31% vs. 82.86%, p=0.000271).

Conclusion: These findings highlight the need for systematic strengthening of educational content and continuous medical education in PV, with an emphasis on practical examples, simulations, and direct exposure to adverse reaction reporting procedures.

Keywords: healthcare professionals, students, pharmacovigilance system, knowledge and attitudes

MCQ, multiple chose questionnaire; QPPV, qualified person for pharmacovigilance; SmPC, summary of product characteristics; PIL, patient information leaflet; MALMED, Macedonian agency for medicines and medical devices; PV, pharmacovigilance; ADR, adverse drug reaction; CNS, central nervous system; PSUR, in periodic safety update reports; RMP, risk management plan; EMA, european medicine agency

Drug safety represents one of the key aspects in the process of drug development and use. A drug is considered safe if its expected benefits significantly outweigh the potential risks of adverse reactions when used appropriately.1,2 Nevertheless, every drug can cause adverse effects — varying in frequency, form, and severity.

Each new drug undergoes a pre-marketing phase, which is a complex and extensive process consisting of preclinical studies on experimental animals (to assess toxicological properties, pharmacokinetics, and potential efficacy) and clinical trials in humans (divided into three phases, designed for the systematic evaluation of safety, efficacy, and the benefit–risk ratio, based on a pre-approved protocol, in strictly selected participants from a defined patient population, for a specific indication).3 However, these studies are performed on a limited number of subjects and within a restricted timeframe, providing data on the most common adverse reactions, but not on rare or delayed effects.2

Following drug registration, i.e., approval by a regulatory authority, the drug is placed on the market and used in everyday clinical practice in a broader, uncontrolled, and more diverse population. This increases the likelihood of new, rare, or unexpected serious reactions, unknown effects of long-term use, drug–drug interactions in patients receiving multiple therapies, medical errors (arising from complex regimens or look-alike/sound-alike drug names), off-label use (beyond the approved indication), misuse or abuse (particularly in psychoactive drugs), and administration in vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and patients with chronic conditions (e.g., hepatic or renal insufficiency).1,4,5

Post-marketing surveillance requires the establishment of a system to monitor drug effects in real-world practice, including the collection and analysis of safety data after marketing authorization, known as PV. According to the WHO, PV is defined as “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problem”.6,7 The Law on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices of the Republic of North Macedonia defines PV as a set of activities related to the detection, assessment, understanding, prevention, and management of adverse drug reactions, as well as new information regarding adverse reactions or risks associated with drug use.1,8 Through post-marketing studies and adverse event reporting the safety profile is further complemented, warnings are introduced into package inserts and summary product characteristics, and in some cases, restrictions are applied or the drug is withdrawn from the market.3,9

Spontaneous reporting represents a fundamental pillar of the PV system and plays a key role in identifying and monitoring the safety profile of drugs after they are marketed.4,7 It relies on voluntary reporting of suspected adverse reactions by healthcare professionals (physicians, pharmacists, and nurses), patients, and other stakeholders, without a pre-structured study. Spontaneous reporting is essential for detecting new and rare adverse reactions because clinical trials are usually limited in number and duration. Such reports allow identification of reactions that occur rarely or after prolonged use, and they provide insight into effects in populations not included in clinical trials (e.g., children, elderly, pregnant women, patients with chronic diseases), as well as detection of drug interactions and misuse. These reports reflect real-world clinical practice since they come from everyday clinical use, representing the “actual” use of the drug. Through spontaneous reporting, the speed and quality of regulatory response can be improved; with a sufficient number of signals, a drug can be withdrawn, the SmPC or PIL revised, or restrictions imposed. Spontaneous reporting is a simple, cost-effective, and efficient method for identifying new drug risks in real practice. Without it, many serious adverse effects would remain undetected. Despite its importance, spontaneous reporting has challenges and limitations: only 5–10% of all adverse reactions are reported, and data quality is often low, with insufficient information to establish a definitive causal relationship.10

In the past decade, new European directives (2010/84/EU) and regulations ((EU) No 1235/2010) on PV have been introduced. These amendments came into force in July 2012 and have been gradually implemented since 2015, with the aim of strengthening the drug safety system through greater transparency, enhanced risk assessment, improved monitoring and coordination, and the active involvement of healthcare professionals and patients in reporting adverse reactions.2,3

According to EMA and MALMED guidelines, healthcare professionals are required to report any suspected adverse reaction, regardless of severity or the certainty of causality.1,8 Without active participation of healthcare professionals, the PV system cannot function fully.4,11,12 The Qualified Person for Pharmacovigilance (QPPV) is a key figure in the drug safety system within pharmaceutical companies and marketing authorization holders. According to the Law on Medicines and Medical Devices of the Republic of North Macedonia, this should be a physician or pharmacist appropriately trained in PV.1,8 Their role is central to organized, timely, and accurate reporting of adverse reactions, which forms the basis for patient safety. The QPPV is not merely an administrative role but a pillar of the drug safety system and an active participant in PV.

According to the Law on Medicines and Medical Devices, healthcare professionals who come into contact with patients, drug manufacturers, marketing authorization holders, and wholesalers are obliged to notify the Agency of:

Healthcare professionals — particularly physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and dentists — are key elements in PV, as they are directly involved in prescribing, dispensing, and monitoring drug therapy.11–15 Their knowledge, clinical experience, and direct access to patients are crucial for the timely detection, assessment, and minimization of risks related to drug use.

Aim

The main objective of our study is to assess the knowledge and attitudes regarding the PV system among healthcare professionals (medical doctors, pharmacists, and nurses/medical technicians employed in various positions) and medical students.

The research was designed as a descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study for assessment of the knowledge and attitudes regarding the PV system.

A total of 119 respondents participated in the study: 70 healthcare professionals (individuals responsible for the PV system among marketing authorization holders in the Republic of North Macedonia, of whom the majority - 70% were pharmacists) and 49 medical students who had successfully passed the pharmacology exam.

(Table 1–Table 3)

|

Education |

N |

% |

|

|

Healthcare professionals |

Faculty of Medicine |

8 |

6.72 |

|

Faculty of Pharmacy |

49 |

41.18 |

|

|

Faculty of Veterine |

2 |

1.68 |

|

|

Other University degree (Faculty of Natural Sciences and other) |

7 |

5.88 |

|

|

High school graduated in medical field |

3 |

2.52 |

|

|

Medical Technician |

1 |

0.84 |

|

|

Medical Students |

49 |

41.18 |

|

Table 1 Education data

|

Mean |

Min |

Max |

SD |

|

30.28 |

21.0 |

54.0 |

9.823996 |

Table 2 Average age of respondents (years)

|

Variable |

No |

% |

|

Men |

30 |

25.21 |

|

Women |

89 |

74.79 |

Table 3 Respondent gender

The research was conducted using an anonymous questionnaire (MCQ) consisting of 19 questions, over a period of two years (2023–2025).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Statistical analysis

The collected data were processed using the statistical software package SPSS for Windows 13.0:

The results are presented in tables and figures.

|

Knowledge of the pharmacovigilance system and attended training |

Participants |

|

|

No |

% |

|

|

Yes |

25 |

21.00 |

|

No |

92 |

77.32 |

|

Unknown |

1 |

0.84 |

Table 4 Data on knowledge of the pharmacovigilance system and attended training

Before conducting the survey, it was determined that only 21% of the respondents had received specific training in PV.

Out of the 19 questions posed, the answers to 12 questions were similar in both groups of respondents, and no statistically significant difference was demonstrated. (Table 4 & Table 5)

|

Question |

Offered answers |

Correct answer |

Employees |

Students |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

|||

|

What is an adverse drug reaction? |

А) Appropriate response to the use of a drug or medical device. B) Any adverse and harmful reaction to a drug that occurs when the drug is used according to the prescribed method of use. C) Change in the color of the medication. |

B) |

70 |

100 |

49 |

100 |

|

Which adverse reactions are reported? |

A) serious adverse reactions B) non-serious adverse reactions C) expected D) unexpected E) all F) none of the above |

Е) |

66 |

94.29 |

47 |

95.92 |

|

Within what time frame should a report be submitted for a serious ADR without a fatal outcome? |

A) there is no deadline B) 24 hours C) 15 days |

C) |

56 |

80 |

34 |

69.39 |

|

Within what time frame should a report be submitted for a serious ADR with a fatal outcome |

A) there is no deadline B) 24 hours C) 15 days |

B) |

66 |

94.29 |

44 |

89.8 |

|

"How can an ADR be reported to MALMED? |

A) via e-mail on the website www.malmed.gov.mk B) by filling out an application form through the MALMED Archive C) both ways |

C) |

67 |

95.71 |

45 |

91.84 |

|

Who can report an ADR? |

A) doctor, nurse, pharmacist B) patient C) family member, caregiver, relative D) all of the above |

D) |

66 |

94.29 |

44 |

89.8 |

|

Where is the processed report of ADR from the National PV Centre forwarded? |

A) Ministry of Health B) Global Database – Uppsala Monitoring Center C) European Medicines Agency |

B) |

62 |

88.57 |

44 |

89.8 |

|

What are the goals of pharmacovigilance? |

A) adverse drug events/reactions B) counterfeit drugs C) drug interactions D) drug abuse and overdose E) all of the above |

E) |

61 |

87.14 |

37 |

75.51 |

|

In which section of the summary of product characteristics can the described ADR be found? |

A) in 4.8 B) in 4.1 C) in 4.4 |

А) |

50 |

71.43 |

36 |

73.47 |

|

Who are not targets of pharmacovigilance? |

A) Adverse drug events/reactions B) Drug interactions C) Drug abuse and overdose D) Drug ineffectiveness E) Drug advertising F) Off-label use |

E) |

54 |

77.14 |

40 |

81.63 |

|

Should off-label use of a drug be reported to MALMED? |

А) Yes B) No |

А) |

68 |

97.14 |

47 |

95.92 |

|

Should PSURs be submitted for medicines that have an indefinite marketing authorisation? |

А) Yes B) No |

А) |

67 |

95.71 |

46 |

93.88 |

Table 5 Results of the 12 questions for which no statistically significant difference exists between employed respondents and students (p<0.05)

Employees (active stakeholders) consistently scored higher in time-sensitive and regulatory aspects (reporting deadlines, broader goals of PV). This reflects their practical exposure and responsibilities.

Students showed strong theoretical knowledge, particularly in some areas (SmPC location, targets of PV), but weaker understanding of timelines and broader PV objectives (within what time frame should a report be submitted for a serious ADR with or without a fatal outcome; who can report an ADR and ect.).

There is a statistically significant difference in the responses of the participants to the following six questions from the questionnaire: (Table 6)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (Ministry of Health) |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

0.000072 |

|

B (Institute of Public Health) |

/ |

/ |

1 |

2.04 |

|

|

C (Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (MALMED)) |

70 |

100 |

37 |

75.51 |

|

|

D (Health Insurance Fund) |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

|

E (All of the above) |

/ |

/ |

11 |

22.54 |

|

Table 6 Results of the question: Where an adverse drug reaction should be reported? (Correct answer: C)

All employed participants answered correctly which mean they are familiar with the correct institution for reporting in the Republic of North Macedonia (MALMED), whereas 12 students confuse it with other institutions or select more than one answer. This suggests a lack of clear and practical knowledge among students regarding the actual reporting procedure, likely due to limited PV practice during their studies. (Table 7)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (Patient information, description of the adverse reaction, drug name, and reporter details) |

70 |

100 |

43 |

87.76 |

0.002661 |

|

B (Patient information, expired drug use, and reporter details) |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

|

C (Description of the adverse reaction, tablet colour, and reporter details) |

/ |

/ |

6 |

12.24 |

|

Table 7 Results of the question: Which mandatory data does a healthcare professional fill in the report of an adverse reaction? (Correct answer: A)

Employed participants are significantly more familiar with the required elements for a valid report. This is most likely due to the practical experience of employed participants in filling out reports, as opposed to the theoretical knowledge of students. (Table 8)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (New indications, contraindications) |

/ |

/ |

9 |

18.37 |

0.000381 |

|

B (Removal of existing contraindications) |

/ |

/ |

3 |

6.12 |

|

|

C (Change in the method of dosing) |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

|

|

D (Change in the safety profile of the drug) |

3 |

4.29 |

/ |

/ |

|

|

E (All of the above) |

65 |

92.86 |

36 |

73.47 |

|

|

F (None of the above) |

2 |

2.86 |

1 |

2.04 |

|

Table 8 Results of the question: Based on the received reports, what changes can be made in the content of the SmPC and PIL? (Correct answer: E)

Employed participants more frequently recognize all possible changes (new indications, contraindications, changes in dosing, and the safety profile) as part of the regulatory process, whereas students often limit themselves to only one or two categories of changes. This suggests that students have a partial understanding of the impact of reported adverse reactions on drug safety and the regulatory documents that arise from these reports. (Table 9)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (A confirmed causal relationship between the drug and the adverse reaction is required for reporting) |

11 |

15.71 |

7 |

14.29 |

0.017804 |

|

B (Suspicion that the adverse reaction was caused by the drug) |

52 |

82.86 |

34 |

69.39 |

|

|

C (Adverse reactions are reported only based on the patient’s opinion) |

/ |

/ |

6 |

12.24 |

|

|

No answer |

1 |

1.43 |

2 |

4.08 |

|

Table 9 Results of the question: Which conditions should healthcare professionals report? (Correct answer: B)

Employed participants more frequently adopt the correct approach – reporting even when there is only suspicion, not just when a confirmed causal relationship with the drug exists. Some students refrain from reporting without full certainty, which may lead to underestimation of the real situation and a lower frequency of reported adverse reactions. (Table 10)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (Must be appropriately qualified, trained, and competent personnel to perform pharmacovigilance activities, with higher education in medicine or pharmacy) |

2 |

2.86 |

9 |

18.37 |

0.016367 |

|

B (Must be continuously and readily available) |

/ |

/ |

1 |

2.04 |

|

|

C (Must influence the effectiveness of the quality system and the company’s pharmacovigilance activities and is responsible for establishing and maintaining a pharmacovigilance system) |

/ |

/ |

1 |

2.04 |

|

|

D (All of the above) |

67 |

95.71 |

38 |

77.55 |

|

|

No answer |

1 |

1.43 |

/ |

/ |

|

Table 10 Results of the question: Who is the responsible person for pharmacovigilance? (Correct answer: D)

Employed participants much more frequently recognize the full scope of responsibilities (qualifications, availability, and system maintenance), whereas students often focus on only one segment. This is likely a result of the greater practical familiarity of employed participants with regulations. (Table 11)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (It indicates that the drug has an effect on the CNS) |

2 |

2.86 |

8 |

16.33 |

0.003938 |

|

B (It indicates that the drug should not be used during pregnancy) |

1 |

1.43 |

4 |

8.16 |

|

|

C (It indicates that the drug is subject to additional monitoring) |

66 |

94.29 |

34 |

69.39 |

|

|

No answer |

1 |

1.43 |

3 |

6.12 |

|

Table 11 Results of the question: What does it mean if a drug is marked with a black triangle? (Correct answer: C)

Employed participants more frequently recognize the significance of additional monitoring, whereas students often confuse it with pharmacodynamics characteristics or safety recommendations during pregnancy. This highlights the need for greater emphasis on post-marketing symbols and labels in education. (Table 12)

|

Answers |

Employees |

Students |

p value (Pearson Chi-square) |

||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

A (In Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSUR)) |

8 |

11.43 |

4 |

8.16 |

0.000271 |

|

B (In the Risk Management Plan (RMP)) |

58 |

82.86 |

32 |

65.31 |

|

|

C (In the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)) |

1 |

1.43 |

13 |

26.53 |

|

|

No answer |

3 |

4.29 |

/ |

/ |

|

Table 12 Results of the question: Where are risk minimization measures described? (Correct answer: B)

Employed participants more frequently know that these measures are included in the Risk Management Plan (RMP), whereas students more often locate them in the SmPC or PSUR. This indicates insufficient knowledge of the PV system among students. Figure 1

Figure 1 Comparative knowledge of pharmacovigilance between students and employed pharmaceutical professionals.

The figure shows statistically significant differences in knowledge regarding ADR reporting, mandatory data in ADR reports, possible SmPC/PIL changes, conditions to be reported, QPPV responsibilities, black triangle meaning, and location of risk minimization measures. Employed professionals demonstrated consistently higher knowledge across all domains compared to students (p < 0.05 for all listed domains).

Pharmacovigilance plays a central role in safeguarding patient safety by ensuring the timely detection, reporting, and prevention of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Despite established regulatory requirements, evidence shows that underreporting remains a global challenge, with only a fraction of ADRs being submitted through spontaneous reporting systems.4,7,10 The PV system cannot achieve its full potential in improving therapeutic outcomes and protecting public health without strengthening awareness and knowledge.

Negative experiences from the past indicate that it often took several years or even decades to reach significant discoveries regarding the toxicity of certain drugs, such as aspirin, chloramphenicol, and thalidomide.9 Tragedies caused by drug use due to incomplete information on drug safety inevitably led to the introduction of legal frameworks regulating the relationships among all stakeholders.2

The study results indicate statistically significant differences between students and employed pharmaceutical professionals regarding knowledge and application of PV principles.16,17

According to this study, employed participants were significantly better informed about the PV system. particularly regarding: reporting of adverse reactions, mandatory data to be included in reports, possible changes in the SmPC and PIL based on reported adverse reactions, which conditions should be reported, the duties and responsibilities of the QPPV, and where risk minimization measures are described (82.86%).

The students’ demonstrated statistically significantly lower knowledge compared to employed participants, likely related to their lack of practical work experience. They frequently confused MALMED with other bodies, attributed to the greater practical experience and direct communication of employed participants with regulatory authorities. The students exhibited gaps in administrative knowledge, although theoretically informed. They often mentioned only some possible changes in SmPC and PIL and they need a more complete understanding of regulatory interventions. The students required a higher knowledge for reporting even the suspicion and threshold of certainty, which may lead to underreporting. It is expected the employed participants to demonstrated greater knowledge of the full scope of QPPV’s responsibilities and tasks, while students focused on a limited subset. The meaning of the black triangle is not clear for the students – they are confusing it with other safety information. The students more frequently mislocated the location of risk minimization measures and the Risk Management Plan (RMP).

Studies conducted in North Macedonia indicate a need for greater education and awareness among healthcare professionals regarding adverse reaction reporting.2,16,17 Similar findings have been observed in other Balkan countries such as Albania,11 Serbia,18 and Montenegro,13 where studies show that education and practical training significantly improve healthcare professional participation in PV.

Globally, barriers to adverse reaction reporting remain, including lack of knowledge, perception that only serious reactions should be reported, and insufficient motivation among healthcare professionals.4,5,10,12 Multiple authors emphasize the need for modernization and integration of PV into medical, pharmacy, and dental curricula.14,19–25 Improved collaboration between healthcare professionals, institutions, and regulatory authorities, along with continuous education, can significantly enhance the quality and quantity of reports.2,9,26

According to published global studies, education of healthcare personnel is crucial for improving knowledge and the quality of adverse effect reporting (Nepal, Jordan, Egypt, and Brazil).19–26 Key conclusions from these studies include:

The results of this study clearly indicate a significant difference in knowledge of the PV system between employed healthcare professionals and students. Employed participants demonstrated a higher level of awareness and accuracy regarding procedures, institutions, and regulatory requirements, likely stemming from their practical experience and direct interaction with the system. In contrast, students, although possessing basic theoretical knowledge, showed insufficient familiarity with administrative and regulatory aspects, as well as with specific responsibilities in post-marketing surveillance.

These findings highlight the need for systematic strengthening of educational content and continuous medical education in PV, with an emphasis on practical examples, simulations, and direct exposure to adverse reaction reporting procedures. Additional education and training, implemented during the study period, could contribute to the development of competent future healthcare professionals capable of actively participating in the PV system and ensuring greater drug safety in clinical practice.

None.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2025 Sadikarijo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.