eISSN: 2379-6367

Short Communication Volume 7 Issue 5

1Poste de Sante Catholique, Senegal

2Le Relais-Maison de l’Artemisia, Senegal

3IFBV-BELHERB, Luxembourg

Correspondence: Pierre Lutgen, IFBV-BELHERB, BP 98 L-6905, Niederanven, Luxembourg

Received: August 22, 2019 | Published: October 11, 2019

Citation: Cissé F, Vandamme P, Binta Sy, et al. Artemisia and beeswax against Tinea capitis (teigne tondante). Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2019;7(5):245-248. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2019.07.00258

A catholic sister in Senegal has developed a very efficient topical treatment against Tinea capitis. It is based on Artemisia extracts, beeswax and a few other minor ingredients.

Keywords: Tinea capitis, Artemisia, drug resistance, antifungal, beeswax

Dermatophytosis, also known as ringworm or tinea, is caused by a group of fungi that infect keratinized tissues in human and animals and are known as dermatophytes. Infection occurs through different ways such as contacting with contaminated soil, hair, or animal scales, and infected individuals. After adhering to keratinized tissues, such as nail, hair, and stratum corneum, dermatophytes release enzymes which break and damage keratinized tissues.

Fungi can evade the immune system via different processes, including recombination, mitosis, and expression of genes involved in oxidative stress responses. These processes can lead to chronic fungal diseases. Despite the growth of health care facilities, the incidence rate of fungal infections is still considerably high. Tinea capitis, teigne tondante in French, Ringworm in English, is a cutaneous fungal infection (dermatophytosis) of the scalp. At least eight species of dermatophytes are associated with Tinea capitis. The clinical presentation is typically single or multiple patches of hair loss, sometimes with a 'black dot' pattern (often with broken-off hairs), that may be accompanied by inflammation, scaling, pustules, and itching. Uncommon in adults, Tinea capitis is predominantly seen in pre-pubertal children, more often boys than girls.

Tinea capitis is a major neglected disease. 200 million cases were registered in 2017. The incidence of fungal infections is escalating worldwide. The serious nature of these infections is compounded by increasing levels of pharmaceutical drug resistance. Tinea capitis always requires systemic (per os) treatment, because topical antifungal agents do not penetrate down to the deepest part of the hair follicle. Furthermore, these drugs are expensive and some have side effects. Our partners in Senegal have developed an ointment which over the last 2-3 years has shown excellent results in the treatment of Tinea capitis. The administration is topical, versus systemic for the above mentioned pharmaceutical drugs. In parallel they use a soap enriched in Artemisia aqueous extracts. They keep records on age, gender, description of disease and treatment outcome. Over the last 15 months 134 persons have been treated. At least 80% have been totally cured with disappearance of the mycosis. A few more recent patients continue the treatment (report is available on request, see excerpt in Table 1).

Date |

Gender |

Age |

City |

Description of disease |

Kind of treatment |

Outcome of treatment |

|

19.03.2019 |

M |

53 months |

Nguinth |

Wounds, allergy, pruritis, tinea capitis |

Artemisia ointment+ Artemisia soap |

Healed |

|

F |

5 months |

Diayane |

Mycosis, pruritis on scalp, tinea capitis |

Artemisia ointment |

Completely healed |

||

F |

33 months |

Thakhio |

Loss of hair, tinea capitis |

Artemisia ointment+ Artemisia soap |

Mycoses disappeared partially and treatment will be continued |

||

19.06.2019 |

F |

11 years |

K.m.elhadj |

Mycosis of scalp, tinea capitits |

Artemisia ointment |

Completely healed |

|

F |

5 months |

Khombole |

Mycosis of scalp, tinea capitis |

Artemisia ointment |

Completely healed |

||

F |

3 years |

Nguinth |

Mycosis of scalp, tinea capitis |

Artemisia ointment |

Completely healed |

||

Table 1 Excerpt of the Excel control tables established by Sr Fr Cissé over the last 2 months

The major components of the ointment are Artemisia annua or Artemisia afra powder, beeswax and groundnut oil. For proprietary reasons we do not want to disclose at this stage the exact composition and the nature of some other minor ingredients of plant origin. The purpose of this document is to investigate the contribution of the three major constituents.

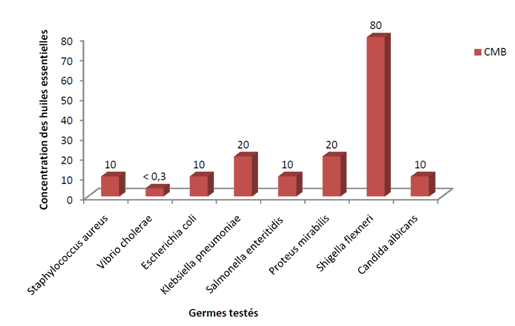

Many encouraging results for the fungicidal properties of Artemisia plants have been reported. This has been demonstrated in Iran for Artemisia scoparia, Artemisia sieberi, Artemisia aucheri. And in Russia for Artemisia maritima, Artemisia austriaca, Artemisia dracunculus, Artemisia abrotanum.1‒4 A seminal work is that of the Université des Montagnes in Cameroon (Figure 1).5

Figure 1 Minimal bactericidal and fungicidal concentrations of the Artemisia annua essential oil on 8 bacterial strains and a Candida Albicans.

In a trial with Artemisia against Malassezia fungi the minimum fungicidal concentrations from most of the strains tested were from 0.78µL/mL to 1.56µL/mL, and only three strains of Malassezia sympodialis required a higher concentration of 3.125µL/mL. Malassezia fungi are known to cause skin disorders.6 But the question remains open, which are the key components of Artemisia plants responsible for their antifungal properties. The antifungal activity of twelve monoterpenes, camphene, (R)-camphor, (R)-carvone, 1,8-cineole, cuminaldehyde, (S)-fenchone, geraniol, (S)-limonene, (R)-linalool, (1R,2S,5R)-menthol, myrcene and thymol was evaluated against several plant pathogenic fungi Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium oxysporum. Limonene and thymol showed the highest potential. Limonene is well present in Artemisia annua.7,8 An Indian study concludes that the strong effects of Artemisia are probably due to the high amount of terpenoids and flavonoids especially the α-thujone content.9

The antifungal activity of Artemisia herba alba was found to be associated with two volatile compounds isolated from the leaves of the plant.10 Ketones and aldehydes play a role too, and Artemisia annua can contain up to 68% of artemisia ketone in its essential oil.11,12 A study in Iran demonstrated that Artemisia sieberi 5% lotion was more effective than clotrimazole 1% lotion in the treatment of Pityriasis versicolor.13,14 Davanone, another constituent of Artemisia plants has antifungal activity. Five tetrahydrofuran sesquiterpenes, so-called davanones isolated from Artemisia lobelii, were tested for antifungal activity. All the compounds inhibited the growth of the fungi. The overall activity of one of them was comparable to that of the antibiotic bifonazole.15 Some amino acids, like aspartic acid, have strong antifungal properties. Artemisia annua is rich in aspartic acid, which is absent in many other plants.16,17

Eugenol and other alcohols which are present in the essential oil of Artemisia also have antifungal properties.18

A major role is probably played by saponins. Artemisia plants contain saponins, some more than others, for example Artemisia annua from Luxembourg much more than the variety from Cameroon, as shown by the froth test.19‒21 Many Artemisia plants have allelopathic properties and this is largely related to tannins. It needs to be studied if tannins also have an antifungal effect. One paper reports that the aqueous extract of a bark has such properties, the organic solvent extracts not.22,23 Herbicides, glyphosate for example, also have inhibitory properties on amino acids. The latter are essential for the growing of plants or fungi (nonregistered paper by John Iachetta, Dow). The aqueous extracts of some medicinal plants, like Artemisia herba alba, growing wild in the Northern Saharian environment of Algeria exhibited good antifungal activities and were capable of reducing growth of fungi responsible for alterations in wheat. The fact that it is the aqueous extract which has these properties indicates that it is related to water soluble substances like saponins, and not only to essential oils.24 Artemisia plants also show antifungal properties for other phytopathogens.25

Beeswax

The interest in natural products for renewed medicinal applications is growing. This is also the case for products from bees: honey, propolis, beeswax, jelly royal. They have been used extensively in popular medicine. Many honeys have significant antifungal activity against clinical isolates of Candida species.26,27 Beeswax is vitamin-rich, containing plenty of vitamin A, which helps to improve wound healing, reduces wrinkles, protects the skin against UV radiation, and stimulates skin cell turnover.28 Retinoic acid, a derivative of vitamin A is active against mycotic infections and tinea when applied topically.29 Four Malaysian honey samples from different floral sources (Gelam, Tualang, Nenas and Acacia) were studied for their ability to inhibit the growth of fungi and yeast strains (Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger, Epidermophyton floccosum, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes). All tested Malaysian honeys except Gelam showed antifungal activity against all species analysed, with the MIC ranging from 25% (v/v) to 50% (v/v) Candida albicans was more susceptible to honey than other species tested.30

Most of these products contain lactoferrin. Lactoferrin is generated by the metabolism of bees. Bee sting contains the highest concentration of lactoferrin. It is secreted by the serous cells of the major and minor salivary glands. It has an iron-chelating property which deprives microorganisms of this essential element. In addition, lactoferrin has demonstrated potent antiviral, antifungal and antiparasitic activity, towards a broad spectrum of species. Lactoferrin exhibits in vitro anti-inflammatory activities and several domains are present within its polypeptide chain that demonstrate antimicrobial effects.31 Lactoferrin was first identified 80 years ago in bovine milk, but isolated only in 1960. It is only found in mammalians, with the highest concentration in colostrum.32

Grapevine powdery mildew, caused by the fungus Erysiphe (Uncinula) necator, is a major disease affecting grape yield and quality worldwide. In conventional vineyards, the disease is controlled mainly by regular applications of sulfur and synthetic fungicides. Research has identified milk and whey as potential replacements for synthetic fungicides and sulfur in the control of powdery mildew. The studies and results of the authors of an Australian paper support the hypothesis that free radical production and the action of lactoferrin are associated with the control of powdery mildew by milk.33 The first function attributed to lactoferrin was related to its capability of sequestering iron. Many other antimicrobial and antiviral functions have been ascribed to lactoferrin. In vitro activity towards human pathogenic fungi on the part of both human and bovine lactoferrin has been well documented as well. The antifungal activity appears to be related to lactoferrin interference with the fungal cell surface rather than iron deprivation and some host-mediated mechanisms of action cannot be ruled out. Lactoferrin also displays anti-parasitic activity, although the molecular mechanisms of such activity are even more complex. This should not be astonishing as even the mechanisms of action of artemisinin are not understood.34

Groundnut oil (huile d’arachide)

Vegetable oils are complex mixtures of essential oils and many papers document their synergistic action with other compounds.35,36

It is the interaction and synergy between these molecules which is responsible for the antifungal efficacy on Tinea capitis, a new field of research.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Cissé, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.