Geometrical setups

A scalar field defined on a four dimensional space time manifold

with a

symmetry is considered in this study. First, classical general relativity and the scalar field defined on

are summarized using a vierbein formalism. The formalism and terminology in this study follow our previous works.21–23 At each point on

, a local Lorentz manifold

with a Poincaé symmetry

is associated, where

is a four–dimensional translation group. On a open neighborhood around any point

, a trivial frame vector is expressed as

, and a trivial vector bundle (frame bundle) can be introduced. An orthonormal basis of

in

and

in

are also introduced. A short–hand notations of

are used through out this study. The Einstein’s equivalent theorem insists an existence of an isomorphism

at any point in

. A metric tensor

in

is mapped to

in

using a vierbein

as

. An orthogonal basis in

and

are respectively expressed as

and

using a vierbein and its inverse. The Einstein convention for repeated indices is used though out this study. In addition, Greek and Roman indices are used for a coordinate on

and

, respectively. A local Lorentz metric and the Levi Civita tensor are respectively defined as

and

with

. Dummy Roman–indices are often abbreviate to dots (or asterisks), when the index pairing of the Einstein convention is obvious, such as

. When multiple dots appear in an expression, pairing must be a left–to–right order at both upper and lower indices, e.g.

. A principal connection of the fiber bundle

is represented as

, which is referred to as the spin connection. The spin connection satisfies a metric compatibility condition as

. A vierbein for

and a

invariant volume form

are introduced. Similarly, the three–dimensional volume form and two–dimensional surface form are also introduced as

and

, respectively. The volume form

is a three–dimensional volume perpendicular to

, and the surface form

is a two–dimensional plane perpendicular to both

and

. Fraktur letters are used for differential forms. A unit of

is used while the reduced Planck constant

and Newtonian gravitational constant

(or the Einstein constant

in our convention) written explicitly. In this units, there are two physical dimensions, the length and mass dimensions, which are denoted as

and

, respectively.

The Lagrangian for pure gravity without the cosmological term and matter fields is expressed as

(1)

(2)

where

is the spin one–form, which is defined as

. A two form

is referred to as the curvature form, that is a rank–

Lorentz tensor on

.

A Lagrangian of a scalar field

can be expressed in the vierbein formalism as

(3)

where

is a potential energy. A scalar–field two–form

is defined as

(4)

Here

is a contraction operator with respect to the trivial coordinate–vector field

. A physical dimension of the scalar field is set as

in this study. In consequence, a Lagrangian form has null physical dimension as

(5)

where

shows the physical dimension of a quantity

. On the other hand, the gravitational Lagrangian has a length square dimension

. An action integral is defined as

(6)

Physical constants in front of the gravitational and scalar–field Lagrangian are chosen to adjust the physical dimension of the action integral to be null. Owing to require a stationary condition on a variation of the action integral with respect to the vierbein form

, one can obtain the Euler–Lagrange equation as

(7)

where

is the energy–momentum three–form of the scalar field, which can be represented as

(8)

Here, rising and lowering Roman indices are performed using a Lorentz metric tensor, e.g.

. A torsionless condition and Klein–Gordon equation can be obtained from

and

, respectively.

The scalar–filed Lagrangian

given in (3) can be expressed using a trivial frame vector in

or

as

(9)

where

is a determinant of a metric tensor

. Here a relation

is used. The Einstein equation (7) can be expressed using components of a trivial basis on

as

(10)

(11)

where

and

are the Ricci and scalar curvature, respectively. An energy–momentum tensor

is defined through the relation

.

Conformal metric and scaled field method

The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric24–27 is considered in the homogeneous and isotropic universe using a coordinate

on

such as;

(12)

where

, and

is a constant related the space–time curvature. This metric can be expressed using a conformal time

as

(13)

From the metric (13) and the torsion–less condition, the spin form can be obtained as

(14)

where

. The lower half is omitted because it is obvious due to antisymmetry of the spin form. From (14) and the surface form, we can obtain the classical Hamiltonian as22

(15)

and the Liouville form as

(16)

A canonical quantization of general relativity requires the commutation relation between the spin form and surface from as22

(17)

and otherwise zero, where

. Here,

and

are operators respectively corresponding to the spin and surface forms, which are formally described as

(18)

The commutation relation (17) can be represented using terms of the FLRM metric. The metric tensor is a functional of two functions

and

other than the integration measure. On the other hand, the Liouville–form (16) includes a derivative

, and it does not have a term

. Therefore, quantization of the system can be performed by replacing a scale faction

by the corresponding operator as

. The conformal–time derivative1

is included only in the last term of (16). Thus, a non–zero component of the commutation relation can be obtained from (16) and (17) as

(19)

where

,

and

,

are three–dimensional spacial vectors. The three–dimensional integration can be expressed as

(20)

On the other hand, the tight hand side of (17) is represented as

(21)

Therefore, the commutation relation is obtained as

(22)

This can be understood as the equal–time commutation relation of the conformal metric. While this commutation relation is obtained from the commutation relation (17), one can obtain the same result based on quantization by Nakanishi28 as shown in Appendix A.

The scalar field can be defined in the conformal metric with

in the Cartesian coordinate for three–dimensional space

(23)

Instead of a polar–coordinate because virbeins are now independent of

. The action integral of a scalar Lagrangian (9) in the conformal FLRW metric can be obtained as29

(24)

using a local conformal coordinate, where

. We note that

for the conformal metric (23). For further discussions, we specify the potential energy as the Higgs–type field as;

(25)

where

and

is real constants. Here the physical dimension of each term is given as;

(26)

This field

is provided owing to scale the scalar field

by the conformal function

, which is referred to as the scaled scalar field (SSF). While a quartic term has no corrections, a quadratic term receives corrections from the conformal function and its second derivative. According to a standard procedure for field quantization (canonical quantization), the field and its conjugate momentum are replaced by corresponding operators. Here, the non–zero component of equal–time commutation relations of the SSF are naturally introduced from (21) as;

(27)

where

is a scaler field operator. The overall factor

can absorbed by re–definition of the scalar field. Although the

is an operator, it is assumed to commutes each other as

. Non–commutativity of

and

is induced by that of

and

.

Since the commutation relation (27) for the scaled–field operator

is the same as the standard Klein–Gordon field–operator, the standard procedure of the field quantization in a momentum space using the Fock Hilbert–space can be performed as usual. We note that, in the SSF formalism, the commutation relation is required only on the space–time metric (vierbein). Any observers in the local space time cannot observe the scalar field independently form the space time metric. This is one of a realization of the concept given in Kurihara30 such that “Classical mechanics in the stochastic space is equivalent to quantum mechanics on the standard space time manifold”. According to this concept, only the vierbein is quantized using the quantum commutation relations with keeping the scalar field classical. Even if the local observer is in the flat space–time, one may observe the SSF which is quantized due to the quantum space time. From equations (24) and (25), the effective potential can be obtained as;

(28)

where

(29)

An effective mass of the SSF has time dependence through the relation (29), and the electroweak phase–transition from unbroken to broken phases can occur through it. Although the SSF mass was very small, which corresponds to the unbroken phase, owing to a small value of

and

at the early universe, it can be large as the same as that in the current universe after the inflation due to the second term with a large value of

. In the current universe, the first term of (29) is negligibly small compared with the second term, and the time dependence of the mass term through

is much smaller than the current accuracy of Higgs mass measurements.

A vacuum expectation value

and higgs mass

can be extracted from the effective potential. The Klein–Gordon equation obtained from the action (24) with respect to the scaled field

can be expressed as

(30)

where

. For the uniform and isotoropic universe, one can set

. In this case, the energy–momentum tensor (11) is represented as

(31)

(32)

and other components are zero. This energy–momentum tensor can be interpreted as a density (

) and pressure (

) of a perfect fluid as

and

, respectively.

Friedmann equation

The Einstein equation (10) for perfect fluid with the conformal metric (13) can be expressed as follows:

(33)

(34)

where the curvature

is put buck in this subsection. These equations, refereed to as the Friedmann equations, can be rearranged as

(35)

(36)

When the density and pressure are provided from the SSF, the Friedmann equations have a form

(37)

(38)

If appropriate initial conditions are given, the history of the universe can be obtained by solving equations (30), (37) and (38), simultaneously. Further simplification is possible in this case as follows: A conformal–time derivative of (37) provides a equation

(39)

where the Klein–Gordon equation (30) is used. Under the assumption that the SSF is the uniform and isotoropic, a spacial derivative are set to zero again as

. Therefore, the equation (39) can be expressed as

(40)

Due to definitions of

in (29), its conformal time derivative is expressed as

(41)

Under the assume that higher derivatives of the scale function

are much smaller than both the scale function itself and first derivative of that, the first term on the righthand side can be ignored compared with the second term. The validity of this assumption will be confirmed later in this section. In this case, the equation (40) can be approximated as

(42)

where

is assumed through any

. This equation can be express using the proper time

using a relation

as

(43)

The second Friedmann equation (38) can be approximated under the same assumptions as

(44)

Above two Friemann equations (43) and (44) must be consistent each other within the approximation. It leads a following differential equation

(45)

with respect to the conformal time

. This equation can be solved as

(46)

where

. This solution does not give any oscillating fields because of the requirement

.

Numerical calculations

Next the scaling function for the cosmic inflation era is treated in this section. During the cosmic inflation, a condition

is expected naturally. Due to the definition of the SSF, this condition can be satisfied if

and

during the cosmic inflation. A validity of this assumption will be discussed later in this section. The Friedmann equation (43) can be solved under the assumption as;

(47)

where

with an initial condition of

. Due to the assumption above, the SSF stays constant at

during the inflation. An inflation starting time is set to

. An initial value of the SSF may be given by a quantum fluctuation of the field, which is naturally expected to be an order unity. Here the initial value

in the Planck units is assumed. On the other hand, the Higgs potential parameters,

and

, at the beginning of the universe are set to be the same as the current universe at the tree level for simplicity. From the recent measurement of the Higgs mass,31 the quadratic term can be obtained as

and

. Therefore, the initial value

is obtained in the Planck units as

, where

is the Planck mass in the natural units. In order to make the inflation scenario working well, the e–folding number

defined as

must be greater than or around 70. When the normalization

and the e–folding number

are required, the initial value of the scaling function can be obtained as

. The inflation termination–time can be obtained by solving the

such as

second. In our scenario, a speed of changing a vacuum expectation value was very high, and thus, the SSF vacuum is staying at the origin

for a short period. Then, delayed explosion of the SSF field

caught the vacuum expectation value up and the inflation was terminated. Therefore, the electroweak phase–transition must be the second kind.

The evolution of the scaling function can be fixed completely using above parameters under the approximations. Before a starting time of the inflation, the first term of (29) was much smaller than the second term. At that period, the potential energy of the SSF had a minimum at

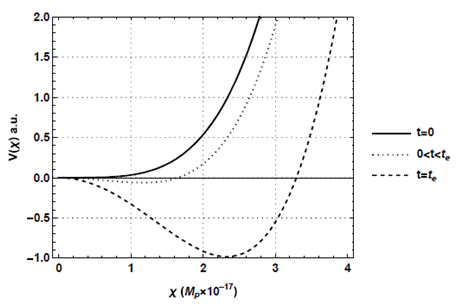

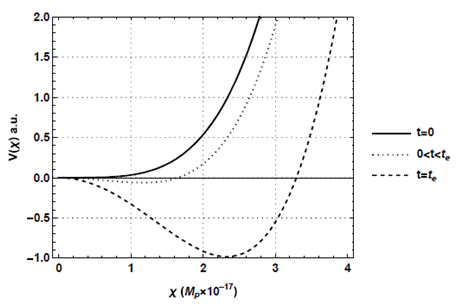

as shown in Figure 1

. During the inflation, the SSF had a finite vacuum expectation value (Figure 1

). At the end of the inflation, the vacuum expectation value arrived at the same value as that in the current universe (Figure 1

). Although the vacuum expectation value stayed almost constant at the beginning inflation, it grew very rapidly after the second term of (29) became dominant in the potential energy as shown in Figure 2. The inflation was terminated when the SSF arrived at the vacuum expectation value, and it fixed the e–folding number. A precise value of the inflation ending time must be evaluated by solving equations (43) and (45) (or equivalently (46)), simultaneously. We note that the relation between the conformal and proper times can be fixed only after the solution of the scaling function is obtained. One cannot solve equations analytically without the approximation that the SFF is constant during the inflation. When the inflation duration changed

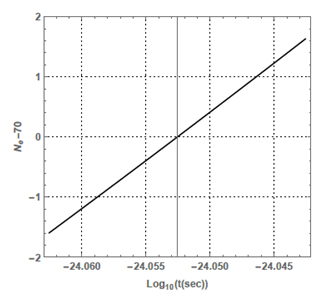

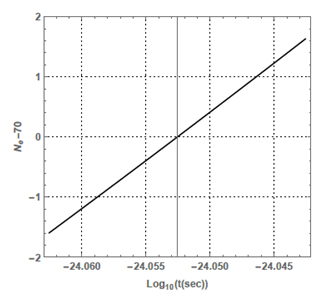

around its nominal value, the e–folding number varied about

as shown in Figure 3. On the other hand, the same variation for the duration of the inflation affects the vacuum expectation value about

to

, as shown in Figure 2. A tolerance of the inflation duration is rather narrow to realize a current observed value of the vacuum expectation value.

Figure 1 The potential energy of the SSF before the inflation (solid line), during the inflation (dotted line), and at the end of the inflation (dashed line).

Figure 2 The potential–energy term of the SSF normalized using the SM value in the current universe. If we require that the cosmic inflation terminated when the potential–energy term of the SSF arrived at the current value

, a duration of the in ation is

second.

Figure 3 The e–folding number different from nominal value

is shown with respect to the duration time of the ination. When the ination duration changed

around its nominal value, the e–folding number varied about

.

The solution (47) is obtained under the assumption of

. The validity of this assumption during the cosmic inflation must be confirmed. If the time dependence of the SSF is put back in the solution as

, the time derivative of the scaling function becomes

(48)

In calculations for the cosmic inflation, the time derivative term in the right hand side is neglected. The validity of this approximation can be examined using the equation of motion. The time evolution of the SSF is governed by the equation (46) with respect to the conformal time. For a conversion from the conformal time to the proper time, the approximated solution of (47) is used for a numerical calculation. A numerical result of a time evolution of the tern

is shown in Figure 4. It is shown that that term is less than unity during the cosmic inflation, and thus the effect on the result is a factor of two on

at most.

Figure 4 A term

is shown with respect to the inflation duration. The approximation used in this report requires a value must be small compare with unity.