eISSN: 2377-4304

Case Report Volume 15 Issue 5

Ministry of Higher Education, Iraq

Correspondence: Saadi AlJadir, MB ChB, PhD, MRCP, FACE, FRCP (L), FRCP (G), Ministry of Higher Education, AlMansour, AlMutanabi, District 607, Alley 20, House 9, Baghdad, Iraq, Tel +964 7813902926

Received: October 13, 2024 | Published: October 28, 2024

Citation: AlJadir S. Unveiling a syndrome through recurrent hypoglycemia. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2024;15(5):247-253. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2024.15.00767

Post-partum hypopituitarism, widely known as Sheehan syndrome, is an ischemic necrosis of the pituitary gland. This event is the result of profound hypotension that is usually caused by massive bleeding or less often in disseminated intravascular coagulation in the peripartum or more frequently during the postpartum period. The sequelae of this catastrophic event are generally subtle, with varying degrees of anterior pituitary hormonal deficiency. Despite this syndrome decreasing worldwide, some cases are occasionally diagnosed in underdeveloped countries because of the improvements and advances in obstetric overall care, and the long-standing experience and recognition of the syndrome, especially in developed countries. The syndrome often progresses slowly; therefore, clinicians face great challenges in making early diagnoses. The most distinctive feature is usually the history of postpartum bleeding, with failure of lactation, cessation of menstruation, and ill-health with vague symptoms that jeopardize the quality of the patient’s life. We had handled a young lady with previously mentioned symptoms but with striking bouts of recurrent hypoglycemia, especially during long fasting. The early noticeable constellation of symptoms and signs with classical history can facilitate early diagnosis, alleviate morbidity and mortality, and improve the overall quality of the patient's life. Most patients will lead a normal life after they have a timely diagnosis and receive the optimal hormonal substitutions.

Keywords: hypoglycemia, Post-partum hypopituitarism, hormonal deficiency, pregnancy

Sheehan syndrome is postpartum pituitary ischemic infarction in women, first described by the British pathologist Harold L. Sheehan, who differentiated this condition from Simmond’s syndrome, which occurs invariably in men and women and is unrelated to pregnancy.9 Overall progress in peripartum and postpartum care in developed countries has minimized the occurrence of this syndrome. However, there are still sporadic cases detected in developing countries, and I should consider in this setting some social (or rather religious) rituals that are imposed on the victims to decline accepting blood transfusions despite shock and profound hypovolemia!

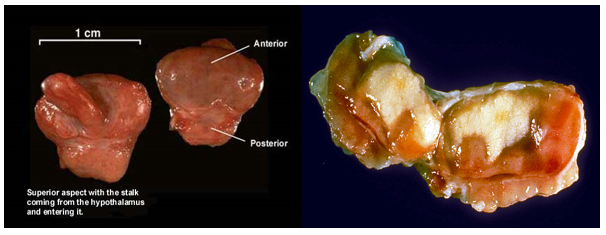

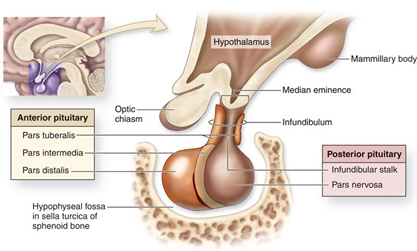

The main culprit of etiology is the damage of the vulnerable anterior pituitary gland during pregnancy, mainly attributed to massive blood loss, particularly during and after delivery, Ischemic necrosis on a variable scale will ensue in the anterior territory of the gland. Generally, the diagnosis of the condition is not feasible immediately after birth, and symptomatology might be showing many months after birth. The early common feature is the absence of lactation; subsequently, other symptoms and signs are associated with a lack of pituitary hormonal production, cessation of menstruation, hot flashes, and decreased libido. Months later, the woman may experience features of thyroid hormonal deficiency; fatigue, mood swings, bradycardia, weight gain, constipation intermingled with adrenal insufficiency in the form of fatigue, loss of weight, loss of axillary and pubic hair, hypotension, and hypoglycemia.2,3 Rarely the posterior hormonal deficiency is involved, and very few reports of some patients might present with diabetes insipidus (Figure 1) (Figure 2).4

Figure 1 The position of the pituitary gland within the skull, courtesy of; national library of medicine.

Figure 2 Gross specimen of the pituitary gland by courtesy to: Junqueira's Basic Histology Text and Atlas (13th Ed).

Pathophysiology

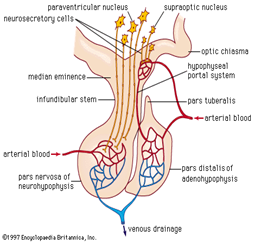

During pregnancy, an increase in pituitary volume as well as cell content usually occurs many weeks before childbirth; moreover, increased estrogen levels cause hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the lactotroph cells, increasing pituitary volume. The volume changes will result in increased nutritional and metabolic demand while not matching the increase in blood supply. Despite the increase in size throughout pregnancy, pituitary functions remain stable and within the normal range. A piece of note: the blood supply of the anterior gland is of the low-pressure portal system Figure 3; hence, it renders the part vulnerable to ischemia. Therefore, the cells in this compartment are susceptible to necrosis in pregnancy, which is usually complicated by postpartum blood loss and shock. The posterior gland has its blood supply, which is under high pressure; therefore, it is still functioning during a shock state. This syndrome typically manifests as panhypopituitarism, or less frequently, as a selective pituitary dysfunction. It also varies in severity, with prolactin and growth hormone severely affected. The posterior pituitary is not commonly affected; hence, only a small number of patients may present with diabetes insipidus.2–6

Figure 3 The inferior hypophyseal artery supplies the posterior lobe, the superior h. a. supplies infundibulum and forms capillary networks from which vessels pass down and form sinusoids into the anterior lobe (Hypophyseal portal system).

Epidemiology

The frequency of SS is decreasing worldwide, and it is a rare cause of hypopituitarism in developed countries because of improvement and progress in obstetric care. However, it is still frequent in underdeveloped and developing countries. Recent epidemiological data obtained from Kashmir Valley has estimated the prevalence to be around 3% of women above 20 years and above; nearly two-thirds of them have the practice of home delivery. 3 in a study of 1034 adult women with hypopituitarism, the sixth most common cause of growth hormone deficiency, SS was responsible for 3.1 % of cases. The national retrospective records (2009) in Iceland the prevalence of SS was estimated to be 5.1/100, 00 women7

Highlights on the history

Sheehan’s syndrome

1913 – Leon Konrad Glinski (1870-1918) was a Polish physician

1914 – Morris Simmonds (1855-1925), a German Physician recognized the clinical features associated with the destruction of the anterior lobe of the pituitary.

1928 – Reye

1937 – Sheehan

In 1949 – Sheehan and Vincent Kirwan Summers (1914-1975) published in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine on the syndrome of hypopituitarism. This early report on pituitary necrosis had given the syndrome of postpartum pituitary insult uniquely the imminent title of Sheehan syndrome.1,8,9

The most common presentation of SS is the long-protracted course; however, some patients present acutely. The dilemma of the presentation might be many months to years elapsed after the inciting event of hypovolemia and shock. The acute presenting condition of Sheehan syndrome is strikingly evident lactation failure or difficulty in initiating lactation. However, many women are asymptomatic for months to years after delivery. Many report gradual cessation of menstruation and some might not have menses after the event but stay so until being diagnosed with SS. The acute form of Sheehan syndrome is presented by profound hypotension and tachycardia associated with hyponatremia and persistent hypoglycemia, the latter two will raise suspicion and will make the diagnosis of SS feasible. The patient may complain of symptoms related to hypothyroidism like fatigue, weakness, hair loss, constipation, weight gain, memory problems or slowing in reaction time, and cold intolerance. Occasionally some Patients may also show features of secondary adrenal insufficiency in the form of fatigue and weight loss.4 Lab values might be helpful in the detection of hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and normochromic normocytic anemia and will establish the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency. Other endocrine failure might be shown as amenorrhea, genital and pubic hair loss, asthenia, weakness, fine wrinkles around the lips and eyes with signs of premature aging, dry skin with hypopigmentation, and other features of hormonal insufficiencies. However, the lack of some evidence like the presence of lactation failure, and amenorrhea doesn’t stand against the diagnosis of SS. Less often patients might present acutely with a shock state, signs of circulatory hypoperfusion, severe hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, diabetes insipidus, and in extreme cases psychotic behavior and cardiac decompensation. Central hypothyroidism and secondary adrenal insufficiency cause free water clearance, moreover, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) are the contributing factors to hyponatremia.2,3,5,6,10

Biochemical evaluations & imaging

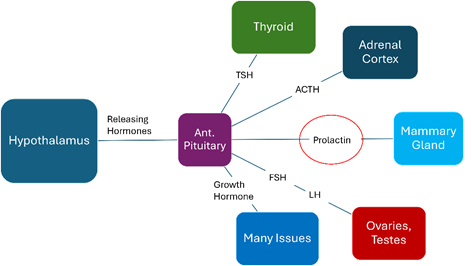

The hormones that are manufactured under central and peripheral feedback (hypothalamus, peripheral target organs) in the anterior pituitary gland are:

The hormones that are affected in SS, are in the following order: GH first followed by PRL, FSH, LH, ACTH, and lastly TSH (Figure 4).

Figure 4 The regulation of anterior Pituitary Hormones (releasing hormones from the Hypothalamus & anterior pituitary hormones production) and the target tissues.

Laboratory tests to order would include a complete blood count (CBC) with differential count, basic metabolic profile, thyroid function tests (TSH, FT3, FT4), FSH, LH, prolactin, estrogen, cortisol, and growth hormone.

Finding a low basal hormone level in the setting of a history and physical features of SS will herald the diagnosis, therefore dynamic tests are usually not required.

Blood pictures may exhibit normocytic/normochromic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and in extreme cases pancytopenia. Hyponatremia and hypoglycemia may also be present as well.

Some authors recommend specific tests for immunological phenomena, as they consider an associated immune basis besides the labor insult.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation of the pituitary is the basic cornerstone of establishing a diagnosis. Generally, the presence of an empty sell in nearly 70% of patients while a partially empty is present in about 30%.in the acute stage, the image may show acute central infarction without bleeding in the hypertrophied gland. Over time subsequent imaging might demonstrate gland atrophy and partially or fully empty sella.10–12

The case history and presentation

Labor history

Clinical impression

Standing: 84/55 mmHg

Working diagnosis

Sheehan’s syndrome: Post-Partum Anterior Pituitary Necrosis (Figure 5) (Figure 6)

Figure 5 Anatomy of the Pituitary Gland, (Permission from Junqueira's Basic Histology Text and Atlas (13th Ed))./p>

Early blood chemistry

|

|

16.09 |

25.09 |

|

S. Na |

132 mmol/L |

135 |

|

S. K |

4.2 mmol/L |

4.1 |

|

S.CL |

100 mmol/L |

104 |

|

S.HCO3 |

20.4 mmol/L |

23.4 |

|

FBG |

3.8 mmo/L |

3.7 |

|

|

(68.4mg) |

(66.6mg) |

Hormonal Profile…

2nd hormonal study

Initial workup 25.09.07

Growth Hormone

Initial blood tests

Blood picture CBP

Urine testing

Imaging: MRI of pituitary gland

Sheehan’s syndrome

Management12–14

Hormonal: Follow-up and adjustment

Thyroid Hormones; early estimate

BP; serials after replacement

On 18.10: sit.94/73 mmHg

st.84/55

On 15.11 105/69 standing

99/68 sitting PR 76/m

The patient is feeling stronger and well.

Next step

Cycle resumption

Oral sequential estrogen & Progesterone in therapeutic doses; started already (progyluton, Schering).

GH replacement15

Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) in adults

On the other hand

GH Therapy

Hormonal Profile Nov.04

Therefore, the L-Thyroxin dose rose to 125mcg OD

Cortisol on serial readings showed variable levels towards the low side, and the Dose of hydrocortisone was scheduled to:

The cycle had been resumed while the Patient had experienced amenorrhea for more than 7 years.

She had taken 2 cycles of therapeutic Estradiol +Progestin, then switched to low dose ES OCs…

Clinical; on Nov.01

Initiating GH: Nov.29

Anemia of chronic diseases

Change in body weight

Current medications

Most recent profile 31.01.08

Blood chemistry

Blood chemistry; serial estimates

|

|

16.09 |

25.09 |

28.1 |

4.11 |

15.11 |

|

S.Na |

132 |

135 |

139 |

141 |

141 |

|

S. K |

4.2 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

|

S.C1 |

100 |

104 |

104 |

106 |

102 |

|

S.HCO3 |

20. |

23. |

26.8 |

29.3 |

31.3 |

|

Blood Glucose |

3.8 (68.4) |

3.7 (66.6) |

5.4 (97.2) |

5.3 (95.4) |

4.7 (84.6) |

And the outcome, Figure 8:

Differential diagnosis

There is a big list of conditions that might mimic SS, though the most that should be considered are:

Owing to the advances in obstetrical care and awareness in developed countries, the prevalence of Post-postpartum pituitary necrosis has appreciably decreased, while still sporadic cases have been detected in developing countries and considered a frequent cause of hypopituitarism in these regions, the main pathogenesis of this disorder is the massive peri or post-partum blood loss, hypovolemia, and shock, that will comprise the blood supply to vulnerable anterior pituitary that ultimately led to infarction and consequently variable degree of hormonal insufficiency. The early diagnosis is still challenging for clinicians. The diagnosis of hypopituitarism is easily overlooked as the symptoms and signs are frequently protean and nonspecific, including changes in electrolyte levels, glycemia, mental status, body temperature, alteration in cardiovascular status, Blood Pressure, and heart rate other involved like blood picture and skin nature. The physician must be vigilant to consider hypopituitarism as the cause for otherwise unexplained abnormal laboratory values and vital signs. The best clues to the diagnosis (as applied to our Case) are the presence of failure of lactation and cessation of the cycle in the setting of a post-partum history of bleeding and hypovolemia. The treatment of patients with SS is often complex because of multiple endocrine deficiencies and consequent abnormalities that require close specific laboratory tests and monitoring during treatment. Patients in whom hypopituitarism is suspected require consultation with a specialist in the field (and probably multidisciplinary collaborations) to assist in management.

The prognosis depends on timely early detection and diagnosis, with appropriate hormonal substitution of paramount concept in alleviating morbidity and mortality and ultimately improving patient quality of life, otherwise, the prognosis will be grave and life-threatening.17–20

None.

Author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2024 AlJadir. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.