eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 3

Department of Obstetrics and gynaecology, University College of Medical Sciences, GTB hospital, India

Correspondence: Anandhita Neelakandan, University College of Medical Sciences, GTB hospital, Quarter no.9, type 4 residential quarters, Old residential colony, IHBAS, Delhi, India, Tel 8220865385

Received: May 03, 2021 | Published: May 17, 2021

Citation: Neelakandan A, Guleria K, Sharma R. Transcervical foley catheter and oxytocin compared with transcervical foley catheter alone for induction of labour. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2021;12(3):145-151. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2021.12.00568

Objective: To evaluate whether transcervical Foley catheter with Oxytocin used concurrently for induction of labour (IOL) increases the delivery rate within 24 hours as compared to transcervical Foley catheter alone.

Methodology: 220 women with Bishop score ≤6 undergoing IOL were randomized into a concurrent transcervical Foley catheter & Oxytocin group and a transcervical Foley catheter alone group and delivery rate ≤24 hours was assessed as primary outcome.

Results: Of the 220 women who completed the trial, there were 110 subjects (52 nulliparae and 58 multiparae) randomized in each group. Delivery rate within 24 hours was > 95% in both groups (96.36% vs 95.45%, p=0.748). Oxytocin use was significantly longer in the concurrent group than in Foley alone group (10.50 vs 7.75 hours).

Multiparae fared better than nulliparae in both the groups in terms of parameters like delivery rate within 24 hours (concurrent group: 100 vs 92.30%, p=0.046; & Foley only group: 98.27 vs 94.23%, p=0.342), delivery in 12 hours, caesarean sections, Foley expulsion time, oxytocin required and successful inductions. They also delivered much faster (combined group: 9 vs 12 hours; Foley only group: 9.41 vs 12.5 hours).

Conclusion: Both methods- combined and Foley catheter alone is equally good for IOL. Concurrent use of oxytocin at the initiation of IOL exposes to a longer duration of oxytocin without expediting the induction thereby questioning oxytocin’s efficacy on the unprimed cervix. Thus concurrent methods (Foley & Oxytocin)) offers no extra advantage over the conventional methods (Foley alone) for IOL.

Keywords: oxytocin, transcervical foley catheter, concurrent/combined methods of induction

IOL, induction of labour; WHO, World Health Organization; FORMOMI, foley or misoprostol for the management of induction

Labor is the presence of regular uterine contractions with progressive cervical dilation and effacement that result in expulsion of the fetus and placenta. Induction of labour is the process of artificially stimulating the uterus to start labour.1 Over the past several decades, the incidence of labour induction has continued to rise. The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health, 2010 observed nearly 3,00,000 deliveries, 9.6% of them were through induction.2–4 WHO Global Survey on patterns and outcomes of induction of labour in Asia 2013 showed that in India 12.8% deliveries were induced.5 Most common indication was postdatism (13.2%).Oxytocin alone was the most common method (37.5%) and success rates were generally over 80%.

Labour can be induced by mechanical, surgical or pharmacological methods. In women with favorable cervix, administration of oxytocin with early amniotomy rather than amniotomy alone is preferred while in those with unfavorable cervix, preinduction cervical ripening increases the likelihood of a successful induction. Hence studies on the combination of oxytocin with other agents like prostaglandins or Foley catheter are required to emphasise on its effectiveness as an inducing agent. Cervical ripening with extra-amniotic balloon catheters like the Foley catheter possesses the advantages of simplicity, low cost, reversibility, and lack of severe side effects and reduced the induction to delivery time.

Several authors have tried to evaluate the various methods of induction and arrive at a method with the shortest induction to delivery time interval. However, the most effective method for inducing labour is yet to be established as there is no standard of care. Recent trials show that for the induction of labour, a combination of methods is more effective than a single method and it is hypothesized that time to delivery would be shorter and rate of deliveries would be higher with combined methods, and also there would be no increase in Caesarean delivery, maternal or neonatal morbidity. In the FORMOMI trial, when two methods were combined, time to delivery was reduced by 3 to 4 hours and rate of delivery in 24 hours increased by almost 15%. If all these women were treated with combination methods, they would spend at least 3.5 million fewer hours in labour. This would in turn lead to a large-scale reduction in the duration of stay of patients in the labour rooms and also reduce the dosages and amounts of pharmacological agents needed and their associated side effects, number of per vaginal examinations thereby reducing the incidence of infections and improving the standard of care for individual patients.

With this background knowledge, the present study was designed with an aim to evaluate whether a combination of two methods of induction – Foley catheter and oxytocin used concurrently will help to increase the rate of delivery within 24 hours and reduce the induction to delivery time interval as compared to transcervical Foley catheter alone. Also, rate of deliveries within 12 hours, rate of caesarean deliveries, time to Foley expulsion, time to active labour, change in Bishop score, dose and duration of Oxytocin use, tachysystole, maternal and neonatal outcomes were compared between the two groups.

This study was conducted in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, from November 2017 to April 2019.

220 women requiring induction and fulfilling selection criteria were recruited (104-nulliparous, 116-multiparous). Subjects were then randomized into Group 1 (n=110)-concurrent transcervical Foley catheter & Oxytocin group and Group 2 (n=110)-transcervical Foley catheter alone group using the lottery method. Group 1 was further sub-divided into Group 1a-nulliparae (n=52), Group 1b- multiparae (n=58) and Group 2 into Group 2a- nulliparae (n=52), Group 2b-multiparae (n=58). After informed written consent, a complete physical and systemic including obstetrical examination, pelvic and cervical assessment was done and pre-induction bishop score was noted. Under aseptic precautions, Foley catheter was inserted into the endocervical canal and inflated with 50cc saline and then taped to the medial aspect of the patient’s thigh with gentle traction. Oxytocin was started concurrently in Group 1. The Bishop score was reassessed at the time of Foley expulsion or at the time of its removal if it wasn’t spontaneously expelled in 12 hours. Subjects found to be in active labour were managed as per hospital protocol with amniotomy and/or oxytocin augmentation and those who did not enter active labour were given oxytocin for 12 more hours (dose titrated as per progress of labour). The vitals, progress of labour and fetal heart rate of the subjects were carefully monitored.

For the purpose of this study, successful induction is defined as women entering into active phase of labour (4cm cervical dilatation and 80% effacement) or delivering vaginally. Failure of induction is defined as failure of subject to enter active stage of labour after 12 hours of oxytocin administration.

At the end of the study data was compiled and analyzed using Univariate Analysis of Variance (UNIANOVA) and Fischer’s Exact Test for comparison between the baseline demographics, clinical and obstetric profiles of the two groups. The number of deliveries within 24 hours and 12 hours in the two groups was compared by Chi-square test. Mann Whitney test was applied to compare the induction to delivery time, preinduction Bishop score, time to Foley expulsion, change in Bishop score, time to active labour, duration of rupture of membranes, duration of various stages of labour, dose and duration of oxytocin and Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes of the neonates between Group 1 and Group 2. Mode of delivery, maternal complications, neonatal outcomes and complications were compared by Chi-square test. Survival analysis was used to assess the mean induction time with successful induction of labour as the end point.

The incidence of induction of labour in the present study was 33.33%. Majority women in both the groups were between 20-30years of age, housewives, from urban area, literate, vegetarian by diet, Hindus and belonged to the upper lower class. Mean period of gestation at the time of recruitment was 39.20±1.70 weeks in group 1 and 39.72 ± 1.50 weeks in group 2. The major indication for induction was postdatism followed by perception of decreased fetal movements, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, oligohydramnios, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction and the mean pre induction Bishop Score was 2 in both the study groups. Comparison of outcomes between the study groups has been given in Table 1.

|

Parameters |

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

P value |

|

Foley + oxytocin |

Foley alone |

||

|

n=110 |

n=110 |

||

|

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

||

|

Delivery in 24 hours |

106 (96.36) |

105 (95.45) |

0.748 |

|

Delivery in 12 hours |

65 (59.09) |

67 (60.90) |

0.89 |

|

Time from induction to delivery (hrs) |

Median |

Median |

0.635 |

|

[interquartile range] |

[interquartile range] |

||

|

11.0 [7.00-15.50] |

10.750 [8.00-16.25] |

||

|

Rate of caesarean |

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

1 |

|

24 (21.81) |

25 (22.72) |

||

|

Time to Foley expulsion (hrs) |

Median |

Median |

0.239 |

|

[interquartile range] |

[interquartile range] |

||

|

2.0 [2.00-3.00] |

2.0 [1.00-3.00] |

||

|

Change in Bishop score |

5.0 [3.00-7.00] |

5.0 [3.00-7.00] |

0.565 |

|

Time to active labour (hrs) |

5.0 [2.00-7.00] |

5.0 [3.00-7.00] |

0.656 |

|

Duration of rupture of membranes (hrs) |

5.0 [3.68-6.00] |

5.0 [4.00-7.00] |

0.68 |

|

Duration of first stage (hrs) |

7.0 [5.50-9.50] |

7.0 [5.50-9.00] |

0.509 |

|

Duration of second stage (hrs) |

0.33 [0.25-0.50] |

0.33 [0.25-0.50] |

0.692 |

|

Duration of third stage (min) |

3.00 [2.00-3.00] |

2.00 [2.00-3.00] |

0.053 |

|

Duration of oxytocin (hrs) |

10.50 [6.87-10.50] |

7.75 [5.50-11.00] |

0 |

|

Dose of oxytocin (mU) |

64.00 [64.00-64.00] |

64.00 [64.00-64.00] |

0.079 |

|

Outcome |

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

0.18 |

|

Successful |

93 (84.54) |

95 (86.36) |

|

|

Failed |

17 (15.45) |

15 (13.63) |

Table 1 Comparison of outcomes between the study groups

*p value ≤0.05 has been considered as significant

Rate of delivery in 24 hours was more than 95 % in both the groups (96.36% vs 95.45%, p=0.748) while 61 % subjects in group 1 and 59% subjects in group 2 delivered within 12 hours. Median time interval from induction to delivery was 11 hours in the concurrent group and 10.75 hours in the Foley only group. Rate of caesarean section was 21.81% in group 1 vs 22.72% in group 2. Median time of Foley expulsion in both the groups was 2 hours. A significant improvement in the Bishop score was noted in both the groups (from a preinduction score of 2 to 5) irrespective of parity.

Time taken to enter active labour was about 5 hours from the time of insertion of the Foley catheter in both the groups. Almost all the subjects of group 1 and group 2 required oxytocin at a maximum rate of 64mU/min for developing adequate uterine contractions.

The duration of oxytocin use was significantly longer in the concurrent group than in the Foley alone group (10.50 vs 7.75 hours). The proportion of successful inductions in group 2 was marginally higher than in group 1 (86.36 vs 84.54%), but not statistically significant. Subgroup analysis of comparison of outcomes between nulliparous and multiparous women in Group 1 has been given in Table 2 and between nulliparous and multiparous women in Group 2 have been given in Table 3.

|

Parameters |

Group 1a |

Group 1b |

P value |

|

Nulliparous |

Multiparous |

||

|

n=52 |

n=58 |

||

|

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

||

|

Delivery in 24 (hours) |

48 (92.30) |

58 (100) |

0.046 |

|

Delivery in 12 (hours) |

24 (46.15) |

41 (70.68) |

0.011 |

|

Time from induction to delivery (hrs) |

Median |

Median |

0.002 |

|

[interquartile range] |

[interquartile range] |

||

|

12.0 [9.00-18.24] |

9.0 [6.00-13.12] |

||

|

Rate of caesarean number (%) |

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

0.038 |

|

16 (30.76) |

8 (13.79) |

||

|

Time to Foley expulsion (hrs) |

Median |

Median |

0.029 |

|

[interquartile range] |

[interquartile range] |

||

|

2.50 [2.00-3.00] |

2.00 [1.50-3.00] |

||

|

Change in Bishop score |

4.50 [3.00-7.00] |

5.50 [3.00-7.00] |

0.137 |

|

Time to active labour (hrs) |

6.00 [3.00-7.75] |

3.50 [2.00-7.00] |

0.058 |

|

Duration of rupture of membranes (hrs) |

5.83 [4.12-6.87] |

5.00 [3.00-6.00] |

0.015 |

|

Duration of first stage (hrs) |

9.00 [5.62-10.75] |

7.00 [5.00-9.07] |

0.085 |

|

Duration of second stage (hrs) |

0.33[0.25-0.50] |

0.33 [0.16-0.37] |

0.1 |

|

Duration of third stage (min) |

3.00 [2.00-3.00] |

3.00 [2.00-3.00] |

0.337 |

|

Duration of oxytocin (hrs) |

12.0 [8.25-15.50] |

9.00 [6.00-12.62] |

0.013 |

|

Dose of oxytocin (mU) |

64 [64.00-64.00] |

64 [64.00-64.00] |

0.067 |

|

Outcome |

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

0.429 |

|

Successful |

42 (80.76) |

51 (87.93) |

|

|

Failed |

10 (19.23) |

7 (12.06) |

Table 2 Comparison of outcomes between nulliparous and multiparous women in Group 1

*p value ≤0.05 has been considered as significant

|

Parameter |

Group 2a |

Group 2b |

P value |

|

Nulliparous n=52 |

Multiparous n=58 |

||

|

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

||

|

Delivery in 24 hours |

49 (94.23) |

57 (98.27) |

0.342 |

|

Delivery in 12 hours |

23 (44.23) |

44 (75.86) |

0 |

|

Time from induction to delivery (hrs) |

Median |

Median |

0 |

|

[interquartile range] |

[interquartile range] |

||

|

12.50 [9.62-19.62] |

9.41[7.00-11.74] |

||

|

Rate of caesarean |

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

0.07 |

|

Number (%) |

16 (30.76) |

9 (15.51) |

|

|

Time to Foley expulsion (hrs) |

Median |

Median |

0.085 |

|

[interquartile range] |

[interquartile range] |

||

|

2.0 [2.00-4.00] |

2.0 [1.00-3.00] |

||

|

Change in Bishop score |

4.0 [3.00-6.75] |

5.0 [3.00-7.00] |

0.256 |

|

Time to active labour (hrs) |

6.0 [4.00-6.00] |

5.0 [2.62-6.00] |

0.024 |

|

Duration of rupture of membranes (hrs) |

6.0 [4.50-7.87] |

4.25 [3.00-6.00] |

0.001 |

|

Duration of first stage (hrs) |

8.0 [6.25-11.00] |

6.50 [5.00-8.25] |

0.006 |

|

Duration of second stage (hrs) |

0.33 [0.25-0.87] |

0.33 [0.25-0.41] |

0.157 |

|

Duration of third stage (min) |

3.0 [2.00-3.00] |

2.0 [2.00-3.00] |

0.182 |

|

Duration of oxytocin (hrs) |

9.00 [6.12-13.37] |

6.50 [4.50-9.00] |

0.001 |

|

Dose of oxytocin (mU) |

64.0 [64.00-64.00] |

64.0 [64.00-64.00] |

0.195 |

|

Outcome |

Number (%) |

Number (%) |

0.405 |

|

Successful |

43 (82.69) |

52 (89.65) |

|

|

Failed |

9 (17.30) |

6 (10.34) |

Table 3 Comparison of outcomes between nulliparous and multiparous women of Group 2

*p value ≤0.05 has been considered as significant

Survival analysis

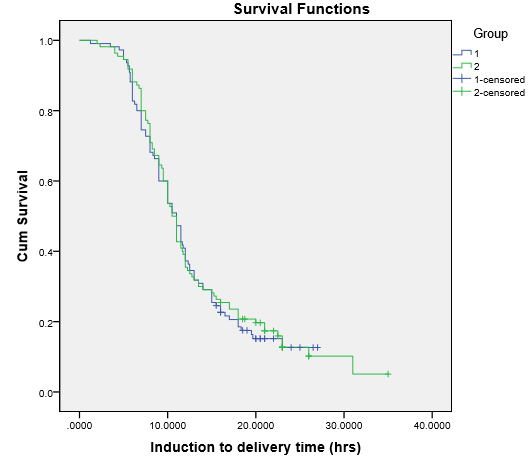

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the length of time after randomization until occurrence of the primary end point (delivery within 24 hours) were presented for both groups.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for number of women undelivered per hour of induction by the log-rank test–Group 1 vs Group 2 has been depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for number of women undelivered per hour of induction by the log-rank test – Group 1 vs Group 2.

The difference in the survival times by the log-rank test (probability of women left undelivered at the end of 24 hours) was not significantly different between the two different methods of induction of labour (p=0.786). Thus while offering the methods of induction of labour to a patient on the basis of such results, the new method (concurrent Foley catheter and oxytocin) cannot guarantee superior results or outcomes.

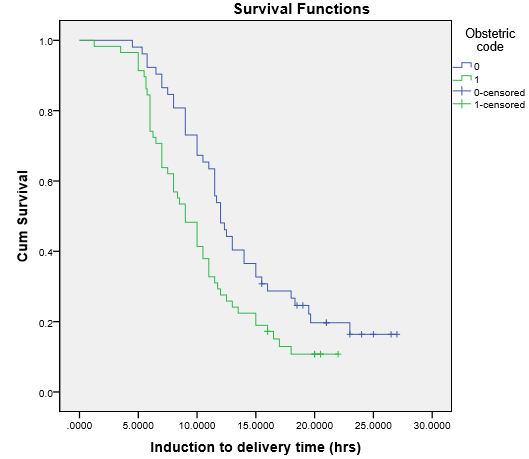

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for number of women undelivered per hour of induction by the log-rank test–Group 1a vs Group 1b has been depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for number of women undelivered per hour of induction by the log-rank test – Group 1a vs Group 1b.

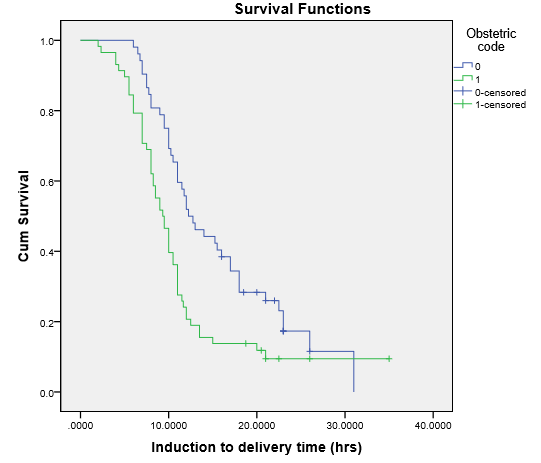

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for number of women undelivered per hour of induction by the log-rank test–Group 2a vs Group 2b has been depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for number of women undelivered per hour of induction by the log-rank test – Group 2a vs Group 2b.

When the 2 subgroups (nulliparae and multiparae) of Group 1 study population were analysed using Kaplan Meier survival curves, the difference in the survival times was statistically significant (p=0.012) as was with Group 2 (p=0.003). The probability of patients being undelivered at 24 hours after induction of labour was significantly more in nulliparous women as compared to multiparous women.

In other words both the methods individually offered superior outcomes in multiparous women as compared to nulliparous women.

Induction is the process that stimulates childbirth and delivery. Over the past several decades, the incidence of labour induction has continued to rise. With the increasing incidence of induction of labour, the agents used for IOL have also seen paradigm shifts and it is being hypothesized that a combination of different methods of induction may have a synergistic effect in achieving labour while reducing the individual method adverse effects. In the current study thus we attempted to compare the efficacy of a combination of Foley catheter and Oxytocin vs Foley catheter alone for the induction of labour.

Among the sociodemographic factors, the population in present study was slightly younger than reported in studies from abroad. This difference could be the result of early marriage and child bearing in our country.

The period of gestation at induction in the current study was similar between the two groups (39.20 vs 39.72 wks) and similar to that quoted in literature; 39.2 vs 38.9 weeks (Schoen’s study) , 39.2 vs 38.7 weeks (Pettker’s study) and 39.1, 39,6, 39.3 and 39.1 weeks (FORMOMI trial). The commonest indication for IOL in the current study was postdatism followed by decreased perception of fetal movements, IHCP, oligohydramnios and gestational hypertension and comparable in both the groups. In other reported studies also, the commonest indications included postdatism, oligohydramnios and preeclampsia. Overall postdatism seems to be the most common indication in most studies.6–8 The preinduction Bishop score was 2 and similar in both the groups. The subjects of the FORMOMI trial had a mean pre-induction score of 3, while women in Schoen et al’s study had a preinduction score of 4 vs 3 and Pettker’s study subjects had a pre induction score of 3.6–8 The highly unfavorable mean pre-induction bishop scores in the present study might have impacted the final outcomes.

As per the recruitment policy, the number of nulliparae and multiparae was predecided in the current study (52 nulliparae in each group and 58 multiparae in each group). Other major trials had a larger proportion of nulliparous population in contrast to the present study population composition.7

The rate of delivery in 24 hours and 12 hours and induction to delivery interval was almost similar between the two study groups indicating no additional advantage of combining Foley with oxytocin as a concurrent method over Foley alone. However, the proportion of multiparous women who delivered within 24 hours and 12 hours was significantly larger than the nulliparous women in both the groups and they also delivered much earlier (about 3 hours) than the nulliparae. The initial trial by Pettker et al also found no benefit in adding concurrent oxytocin for increasing delivery within 24 hours, but this trial did not power the primary outcome for parity.6 However other similar studies found that labour induction with Foley catheter and concurrent oxytocin shortens the time to delivery and increases the rate of delivery within 24 hours compared with cervical ripening with a Foley catheter followed by oxytocin and this was true for both nulliparous and multiparous women in these studies.7 The Foley Balloon Induction of Labour Trial in Nulliparae by Connelly et al found a reduction in time to delivery for nulliparous women who received simultaneous oxytocin with Foley catheter for induction compared with Foley alone.9 The Foley or Misoprostol for the Management of Induction trial initially showed a 3-hour benefit for Foley and oxytocin compared with Foley alone, but this was no longer significant after adjusting for parity.8

The rate of caesarean section was also similar in the two groups in this study, but the multiparae of the concurrent method group had a significantly lesser number of caesarean sections. No significant difference in the caesarean section rate was noted in the previous studies overall and when stratified by parity, which is in concordance with the findings of the present study.6

The Foley catheter was expelled by most subjects of both the groups at 2 hours, but the multiparae in the combined methods group expelled it significantly earlier than their nulliparous counterparts. No difference in the time to Foley expulsion was observed by Pettker et al.6 In contrast, Schoen et al demonstrated a significantly earlier expulsion by the combined group subjects irrespective of their parity.7 Thus the concurrent use of oxytocin at the initiation of induction does not seem to expedite the expulsion of the Foley catheter.

There was an improvement in the post Foley expulsion Bishop score in both the groups, however this wasn’t statistically significant. Most studies have not reported post ripening Bishop scores, however there was a significant improvement in the Bishop score post Foley expulsion in the study by Schoen et al.7

Time to active labour was significantly shorter in the multiparous subjects of both the groups. However overall comparison of both the groups did not show any significant difference. In contrast, the FORMOMI trial showed a significant reduction in the time to active labour in the combined methods groups as compared to the individual method groups (about 3 hours earlier).

In previous studies, the total duration of oxytocin infusion was 6.1 hours longer in nulliparous women (18.4 compared with 12.3 hours, P=.001) and 4 hours longer in multiparous women (13.1 compared with 9.1 hours, P=.001) of the study population with combined methods of induction of labour.7 The current study also demonstrated a significantly longer duration of use of oxytocin in the combined method group as compared to the individual method group (10.50 vs 7.75 hours, p=0.000) because oxytocin was started at the start of induction itself. Nevertheless, the duration of oxytocin use in multiparous women was significantly shorter than that in nulliparous women in both the groups (9 vs 12 hours in group 1 and 6.50 vs 9 hours in group 2).

In the present study there were no significant maternal or neonatal complications.

Thus, in the current study, success of IOL was more than 80% with both the methods, suggesting that concurrent method of transcervical Foley catheter with oxytocin is as good as but not superior to Foley catheter alone for IOL. Multiparous women fared better than nulliparous women in both the groups with respect to various parameters. Nonetheless it couldn’t be established as to which of the two methods was better in nulliparous and multiparous women separately. Subjects who are induced with Foley and oxytocin simultaneously are more likely to receive larger amounts of oxytocin without any additional benefits. Thus, while offering new concurrent method combining Foley catheter with oxytocin, one cannot guarantee or assure a superior outcome over the Foley alone.

Over the past several decades, the incidence of labour induction has continued to rise. The search for the most effective method of induction of labour is still on. The ideal inducing agent would be one which reduces the induction to delivery interval, is easy to administer, is cost effective and has lesser adverse effects. Thus, newer methods are being attempted as combinations of the various traditional methods of induction to see if they can have a synergistic effect and thus increase the rate of delivery within 24 hours and reduce the induction to delivery time interval without affecting the rates of Caesarean sections, maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

The present study establishes that transcervical Foley catheter with oxytocin combined and Foley catheter alone are equally good methods of induction, inferring thereby that no one method seems to be superior to the other. Multiparous women fared better than nulliparous women in both the methods of induction of labour (combined and individual) in terms of most maternal outcome parameters. However, the superiority of either method over the other could not be guaranteed in multiparous women.

Thus we can conclude from the current study that transcervical Foley catheter with oxytocin and Foley catheter alone are both effective methods of induction of labour, but the concurrent use of oxytocin at the initiation of induction of labour only seems to expose the subjects to a larger duration of oxytocin and does not confer any leverage in expediting the induction process and raises concern regarding the efficacy of oxytocin on the unprimed cervix.

I am grateful to my Supervisor Dr.Kiran Guleria, co-supervisor Dr.Richa Sharma and Dr. Amita Suneja, Director Professor and Head of the Department, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, UCMS and GTB Hospital for their immense support and encouragement during the conduct of this study.

None.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

©2021 Neelakandan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.