eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 5

Gynecology Service. German hospital. Buenos Aires (CABA), Argentina

Correspondence: Camargo A, Gynecology Service. German hospital. Buenos Aires (CABA), Argentina

Received: October 25, 2019 | Published: October 28, 2021

Citation: Bianchi F, Camargo A, Habich D, et al. The fundamental role of the exploration of the upper abdomen in ovarian cancer surgery. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2021;12(5):337-342. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2021.12.00603

Purpose: Several studies have shown the benefit of cytoreductive surgery in advanced disease, that is why the residual tumor has prognostic value. Our primary objective was to determine the frequency of involvement of the upper abdomen, defined as the extension of the disease above the transverse colon (diaphragm, spleen, gallbladder, stomach, hepatic parenchyma, hepatic capsule, minor omentum, hepatic ilium, pancreas). Our secondary objective was to analyze the possibilities of complete cytoreduction in these patients, their complications and results.

Materials and methods: We retrospectively include patients undergoing primary and secondary cytoreduction due to ovarian carcinoma between January 2008 and December 2012, in the gynecology department of the German Hospital.

Results: One hundred and thirty nine patients with ovarian carcinoma were analyzed. An average age of 60 years (28-90). 91 of them with attempted primary cytoreduction and 48 secondary cytoreduction. In the group of primary cytoreductions we excluded 17 patients that were stages I and II, 20 (22%) of the 74 stages III-IV had upper abdomen involvement, 17 stages III and 3 stages IV. Those stage IV patients were only limited to hepatic intraparenchymal involvement. Of the 48 secondary cytoreductions, 21 (43%) presented upper abdominal involvement. Including both groups we have 30% of upper abdomen compromise. Complete or optimal cytoreduction was achieved in 56% of them.

Conclusion: The exploration of the superior abdomen in ovarian cancer surgery is key, and the approach of this patients by a team of properly trained gynecologists is mandatory if we want to obtain better complete cytoreduction rates.

Every year around 200,000 patients are diagnosed with ovarian cancer, being responsible for more than 125,000 deaths.1 Ovarian carcinoma is mostly diagnosed in advanced stages (stage III),2 characterized by dissemination of the disease in both the pelvis and abdomen. It is the maximum cytoreductive surgery and then the response to chemotherapy that will mark prognosis and survival.3,4 Since 1970s, several studies have shown the benefit of cytoreductive surgery in advanced disease,3,4,7,8 but it is the residual tumor that has prognostic value. So far several definitions of optimal cytoreduction have been proposed.9–11 The GOG (Gynecologic Oncology Group) currently defines it as a residual disease less than 1 cm in its maximum diameter and complete cytoreduction in the absence of macroscopic disease. Despite the knowledge about cytoreduction, it varies widely in the literature from 15% to 85%.4

Surgery in ovarian cancer requires in some circumstances to achieve optimal cytoreduction, resection of the disease located in organs of the upper abdomen, this being one of the greatest obstacles to achieve it.12–16 Therefore the gynecologist oncologist should be familiar in this type of surgery to achieve optimal results.

Our objectives were to determine the frequency of involvement of the upper abdomen, considering as such the extension above the transverse colon (diaphragm, spleen, gallbladder, stomach, hepatic parenchyma, hepatic capsule, minor omentum, hepatic ilium, pancreas). Second, analyze the possibilities of complete cytoreduction in these patients, their complications and results.

We retrospectively include patients undergoing primary and secondary cytoreduction due to ovarian carcinoma between January 2008 and December 2012, in the gynecology department of the German Hospital of Buenos Aires. Only those patients who underwent surgery of the upper abdomen stages III-IV were included. The pre-surgical evaluation was performed with computed tomography (CT), evaluation of ca 125, physical examination and Pet / Tc for patients undergoing secondary cytoreduction. All were operated by the same surgical team. Data were obtained on the medical records of age, tumor grade, histological type, preoperative ca 125, operative time and hospital stay, intraoperative and postoperative complications. Optimal cytoreduction was defined in those patients with tumor residue <1cm and complete in the absence of macroscopic disease.

One hundred and thirty nine patients with ovarian carcinoma diagnostic were analyzed. They had an average age of 60 years (28-90). 91 of them with attempted primary cytoreduction (PCG) and 48 secondary cytoreduction (SCG).

Of the PCG (91 patients) we had 17 stages I and II that were excluded from the analysis and 74 stages III-IV. In this last group just 20 patients (22%) had upper abdomen involvement, 17 stages III and 3 stages IV. Those stage IV patients were only limited to hepatic intraparenchymal involvement.

Of the SCG (48 patients) just 21 (43%) presented upper abdominal involvement (Table 1).

Cytoreduction |

Total |

Upper abdomen involvement |

Involvement of 1-2 organs |

Involvement of more than 2 organs |

Primary |

91 |

20(22%) |

12(60%) |

8(40%) |

Secondary |

48 |

21(43%) |

17(81%) |

4(19%) |

Complete or Optimal |

20(69%) |

3(25%) |

||

Suboptimal |

9(31%) |

9(75%) |

||

Total |

139 |

41 (30%) |

29 |

12 |

Table 1 Cytoreduction

Of 41 patients with upper abdominal involvement, between primary and secondary cytoreduction, the surgical interventions are broken down in Table 2.

Organ involvement |

Number of patients |

Subdiaphragmatic Peritoneum |

18 |

Spleen |

10 |

Gallbladder |

1 |

Stomach |

3 |

Liver Parenchyma |

11 |

Liver Capsule |

17 |

Lesser Omentum |

7 |

Hepatic Hilum |

6 |

Pancreas |

4 |

Mesentery Root |

3 |

Table 2 Upper abdomen involvement

Of the 20 patients with PCG, compromise in 1 or 2 organs was found in 12 patients (60%) and compromise in more than 2 organs was found in the other 8 patients (40%).

Of the 21 patients with secondary cytoreduction, compromise in 1 or 2 organs was found in 17 patients (81%) and compromise in more than 2 organs was found in just 4 patients (19%).

The 85.4% of the tumors were serous and all tumors were grade 3. The average operative time was 244 minutes. The average hospital stay was 9 days and the average ca 125 was 954 U / ml (Table 3).

Facts |

N (%) |

Histology |

41(100%) |

Serous |

35 (85.4%) |

Clear Cells |

3 (7.3%) |

Endomethroids |

3 (7.3%) |

Tumoral Grade |

G3 (100%) |

Surgery Duration |

244 min (99-492) |

Hospital Stay |

9 días (4-29) |

Ca 125 |

954 ( 10.3-8790) |

Table 3 General facts

From the 29 patients with 1 or 2 organ involvement in 20 of them (69%) complete or optimal cytoreduction could be performed. While in the other 9 patients (31%) we performed just suboptimal cytoreduction, the reason was the hepatic hilum compromised in 4 patients, multicenter hepatic parenchyma metastasis in other 4 patients and extensive bilateral diaphragm involvement in 1 patient.

Of the group of patients with commitment in more than 2 organs (12 patients), we could performed a complete or optimal cytoreduction in 3 of them (25%) and in the other 9 (75%) we just did a suboptimal cytoreduction due to hepatic hilum commitments in 2 patients, mesentery root conditions in 3 patients, involvement of the lesser omentum in 3 patients and hepatic parenchyma in 1 patient.

Of the 62 interventions performed on 41 patients, there were 18 complications in 13 patients (31%), which were acceptable for such interventions. Resection of the diaphragmatic peritoneum and hepatic capsule was the most commonly performed surgery representing 27.4% of the interventions in both cases.

Complications associated with upper abdomen surgery were divided into intraoperative and postoperative in Table 4.

Complications |

Intra surgery |

Post surgery |

Diaphragmatic Perforation |

7 |

|

Splenic Injury |

1 |

|

Subphrenic Hematoma |

2 |

|

Subhepatic Abscess |

1 |

|

Abscess in Splenectomy Bed |

1 |

|

Pancreatic Fluid Leak |

1 |

|

Thrombocytosis |

|

7 |

Table 4 Complications

Within the intraoperative 7 diaphragmatic perforations were presented, they were all resolved in the same act, although they were considered as complications, we consider it feasible to interpret them as part of the cytoreduction. Only 2 of them were really accidental. We have 1 splenic injury in which a splenectomy was performed. Postoperative morbidities were 2 sub phrenic hematomas that did not require intervention, 2 abscesses one in a splenectomy area and another sub hepatic that were solved by percutaneous drainage, 1 pancreatic fluid leak that was treated with 0.1 mg of octreotide SC every 8 hours for 5 days, 7 cases of thrombocytosis, of which 6 had platelet counts less than 1,000,000 and 1 higher than this value, which required aspirin antiplatelet, all associated with splenectomy (Figures 1–20).

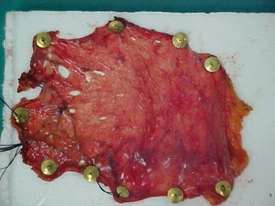

Figure 18 Resection of the right subdiaphragmatic peritoneum less than 1 cm with disease less than 1cm.

All patients undergoing splenectomy received pneumococcal vaccine within the first 14 days of surgery. There were also 5 surgical wound infections, treated without complications, so they were not considered within the complications.

The standard treatment for advanced ovarian cancer today is surgical exploration of the pelvis and abdomen with subsequent maximal cytoreduction followed by systemic/intraperitoneal chemotherapy based on platinum and taxane. The use of cytoreductive surgery was proposed in 1935 by Meigs5 when he published that the greatest amount of tumor should be removed to improve the postoperative effect of radiotherapy. In 1968 Munnell reports that maximum surgical efforts influenced survival.6 In 1975 Griffiths describes an inversely proportional relationship in 102 patients with stage II-III ovarian carcinoma between tumor residue and survival, this being worse if the tumor residue size was greater than 1.5cm.7 In 1992-1994 Hoskins in two GOG trials (52-97) compared adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and cyclophosphamide in patients with stage III disease and with residual disease less than 1cm (GOG 52) or residual disease greater than 1cm (GOG 97) after primary cytoreduction. Survival was higher in patients without visible disease compared to those with residual lesions. And this benefit was also found if residual disease was less than 2cm compared with those greater than 2cm (3.8). A meta-analysis observed that every 10% increase in cytoreduction improved the average survival by 5.5%.4 Current trials report that the absence of macroscopically visible disease has a greater impact on survival than if it is <1cm.17,18

One of the main obstacles to cytoreduction is the involvement of organs of the upper abdomen such as spleen, liver, subdiaphragmatic peritoneum and pancreas tail. Some authors cite that the surgical approach of the upper abdomen cannot be achieved without an increase in morbidity and mortality.13 However, this approach is justified in the survival results obtained by achieving complete or optimal cytoreduction.16 Although the benefit of cytoreduction on overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) decreases as greater tumor volume is present at the time of surgery, it is still optimal cytoreduction that offers the greatest utility in OS and DFS.19 Recent trials publish that the greatest benefit in patients with disease in the upper abdomen in terms of OS and DFS, is observed when complete cytoreduction is achieved, in contrast when it is optimal or with residual disease less than 1 cm in its maximum diameter (54.6 and 40.4 months; 20.2 and 13.6 months, respectively). Whereas if cytoreduction is optimal, upper abdominal involvement does not imply worse OS versus those patients who do not need surgery on the upper abdomen.

While numerous trials support the benefit of upper abdomen surgery, few assess the complications associated with this practice.13,20 The major complications reported are those related to diaphragmatic deperitonization which is associated with pleural effusion between 1530%.21,22 Splenectomy was associated with thromboembolic complications (4.1% -8%), wound infection 6.3%, postoperative pneumonia (4.5-6.1%), sepsis (4.5-12.2%).23 Pancreatic fluid leak was associated with resection of the pancreas tail and spleen in 23%.

In patients treated for stage III-IV ovarian carcinoma at our institution between January 2008 and December 2012, the upper abdomen compromise was 30%. Complete or optimal cytoreduction was achieved in 56% of them, this percentage being 69% when the upper abdomen commitment included only 1 or 2 organs, decreasing to 25% when it committed to 3 or more.

The greatest involvement and interventions performed in our case study was observed in the subdiaphragmatic peritoneum and in the hepatic capsule (27.4% on both occasions)

The complication rate of 31% is considered acceptable considering the radicality of the interventions performed being similar to that reported in the indexed literature.

The exploration of the superior abdomen in ovarian cancer surgery is key, and the approach of these patients by a team of properly trained gynecologists is mandatory if we want to obtain better complete cytoreduction rates.

None.

None.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

©2021 Bianchi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.