eISSN: 2377-4304

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 5

Gynecology Assistance Professor of the Uruguayan Medicine University, Pereira Rossell Hospital, Montevideo, Uruguay

Correspondence: Dr. Fabián Rodríguez Escudero, Gynecology Assistance Professor of the Uruguayan Medicine University, Pereira Rossell Hospital, Montevideo, Uruguay, Tel (+598)99893714

Received: September 02, 2022 | Published: October 24, 2022

Citation: DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2022.13.00672

Stajano, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis Syndrome is a rare clinical presentation of upper genital infections, characterized by few pelvic symptoms and perihepatitis attributed to direct bacterial infection. The perihepatic component usually presents as right hypochondrium pain, tenderness, and "violin strings" hepatophrenic adhesions. This atypical clinical presentation leads to frequent late or misdiagnoses, such as cholecystitis, appendicitis, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, urolithiasis, or hepatophrenic abscesses.

In this paper we carried out a historical review of the knowledge that have occurred over time, of this particular clinical presentation.

Keywords: ginecology, Stajano´s Syndrome, phrenic reaction in gynecology, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis Syndrome, chlamydia, gonococcus

Stajano, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis syndrome is an extrapelvic complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), characterized by pain and tenderness in the right hypochondrium secondary to perihepatitis, few pelvic symptoms, and the presence of adhesions in “violin strings” forms between Glisson's capsule, diaphragm and anterior abdominal wall.1

The clinical picture of a subacute or chronic gonococcal genital infection, which manifests as pain in the right hypochondrium with few pelvic symptoms, was first described by Dr. Carlos Stajano in 1920, publishing two articles in “Anales de la Facultad de Medicina del Uruguay”2,3 and later in the same year in the magazine “La Semana Médica” of Buenos Aires.4 In 1921 JAMA published a summary and English translation of the “La Semana Médica” article.5

In 1922 Stajano published his finding in "Gynecologie et Obstetrique de Paris"6 reaching wide dissemination in the European academic world, whose English summary and translation were published in 1922 by the "American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology".7 The name given by Stajano to this clinical presentation was “phrenic reaction in gynecology”.3

Ten years after the first description, in 1930, Dr. Arthur Hale Curtis published on the frequent coexistence of gonococcal salpingitis and “violin string” adhesions between the anterior surface of the liver and the anterior abdominal wall.8

In 1934, Dr. Thomas Fitz-Hugh Jr. published three women cases who presented with pain in the right hypochondrium due to adhesions between the liver and the abdominal wall, which he attributed to acute gonococcal peritonitis, linking his finding to the picture described by Curtis above.9

In 1978, Dr. Müller described the frequent occurrence in which Chlamydia trachomatis was isolated from the peritoneal fluid in these clinical cases,10 in 1986 Lopez-Zeno linked this germ as the most frequently implicated agent,11 in 1970 Kimball and Knee published the first case of male gonococcal perihepatitis,12 in 2003 Sharma et al. divulgated three cases as a result of genital tuberculosis13 and cases secondary to Tuberculosis ascites,14 and Mycoplasma have recently been published.15

A 27-year-old nulliparous patient with gynecological history of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) at 24 years of age treated with oral antibiotics. After this clinical picture, the patient frequently reports abnormal vaginal discharge that she self-medicates with vaginal suppositories. During last year, she reported occasional pain in the right hypochondrium interpreted as secondary to gallbladder disease, although imaging has not been able to diagnose gallstones or other anomalies that could explain this symptomatology.

Few months ago the condition has worsened, and although it does not show pelvic symptoms, genital examination revealed tenderness on bimanual uterine palpation and cervical motion, and it has not responded satisfactorily to antibiotics treatment, analgesics and anti-inflammatories. It was decided to perform diagnostic and eventually therapeutic laparoscopy thinking on a Stajano, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis Syndrome.

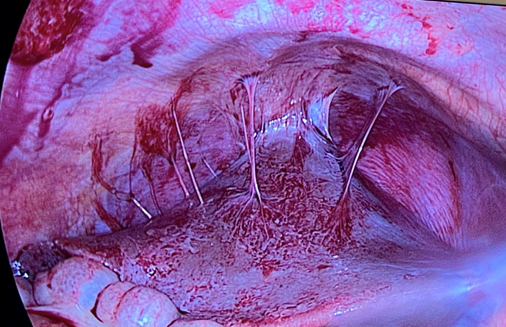

During the procedure, adhesions in a "violin string" form between the liver and the diaphragm, and fluid in the Douglas cul-de-sac, and a genital sub-acute or chronic inflammatory process was observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hepatophrenic adhesions in the “violin strings” form, in a patient with Stajano, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis Syndrome. Photo courtesy of Dr. Gonzalo Sotero.

Adhesiolysis was performed, postoperative antibiotic treatment of PID Is given as indicated, patient responded well for the treatment and was discharge 48 hours after the procedure, follow up was uneventful.

Stajano, Fitz Hugh, Curtis Syndrome is a rare form of chronic PID presentation, presenting with an inflammation of the Glisson's capsule that finally causes perihepatic adhesions in "violin strings" form.1

The patients often have pain in the right hypochondrium with few pelvic symptoms. Occasionally the pain may radiate to the shoulder and is usually increased by Valsalva maneuvers; other times it is accompanied by fever, nausea and vomiting.1

According to the evolution, acute, sub-acute and chronic forms of presentation can be distinguished; the most frequent were the last two.16

During intra-abdominal exploration (laparoscopic or laparotomic), it demonstrate the “violin string” adhesions between the liver and the diaphragm, and less frequently with the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1).8

The incidence is uncertain, although it is known that it frequently affects women of childbearing age who have suffered from PID. In the largest published study to date with 3,564 laparoscopies, this syndrome was diagnosed in 14.8 % of patients with tubal infertility; 6.7 % in ectopic pregnancies and in 1.4 % for other gynecological indications.17 It is possible that this frequency is a little higher in adolescents since evidence of perihepatitis has been found in 27 % of patients with salpingitis,18 and the same it could happen in women with infertility.19

The most frequent etiologic agent is Chlamydia trachomatis, followed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae.1,11

Stajano has explained the reason why these genital infections adopt this curious clinical manifestation. A PID usually determines an endomyoparametritis, and if timely treatment is not given, the condition can evolve into a pyosalpinx, tube-ovarian abscess and pelviperitonitis. Sometimes, secondary to inadequate treatment, etiological agent characteristics or the patient's terrain, the infectious process evolves to a sub-acute or chronic stage. On these occasions, it may happen that the germs ascend from the pelvis, through the right parieto-colic gutter, to the hepatophrenic space.4,20,21 This may be favored by the peritoneal fluid movements secondary to changes in intra-abdominal pressure caused by the inspiratory and expiratory efforts.21,22

Once in the right hypochondrium, the inflammatory process produces a superficial hepatitis that almost exclusively affects Glisson's capsule, with the production of loose adhesions, in the "violin strings" form, between it and the diaphragm and the anterior wall of the hypochondrium.8,9 Hematic and lymphatic have also been postulated as dissemination forms.23,24

In a You et al. review it was reported that the most frequent symptom was pain in the right hypochondrium (71%), and later pain in the hypogastrium (6.1%), in the right flank (4.9%) and pleuritic pain (1.2%).25

Stajano also explained why the pain usually occurs in the right hypochondrium, and not in the mid-abdomen. In the upper abdomen, the vegetative and sensory nerve endings are characterized by the scarcity of underlying cellular tissue, so the inflammatory process rapidly activates the peritoneal pain receptors, while in the peritoneal cavity middle level the nerve pathways cross the muscle fibers, and ends in thicker connective and cellular tissue, which places them farther from the peritoneal surface.20,21

Although the gynecological symptomatology is usually absent, it is rare that it does not manifest itself in some way during the gynecological examination, both during the speculoscopy (cervicitis, vaginal discharge), or during the bimanual examination (pain on uterine palpation, cervix mobilization, adnexal, or pelviperitonitis).1,3

The “violin string” adhesions have usually been found as a laparoscopic finding, in a patient without suspicious symptoms. Tulandi and Falcone26 published that at 4.7% of laparoscopy performed on benign gynecological pathology, “violin string” adhesions can be found on the hepatic surface, which is consistent with that published by Ricci et al.27

This is why; it is always advisable to perform a cautious abdominal examination in women who undergo abdominal laparoscopy, regardless of the reason. If perihepatic adhesions are observed, adhesiolysis is recommended, which does not significantly increase the operating time or complications.28 This practice usually improves symptoms and would avoid the complication derived from hemoperitoneum due to tearing of the hepatic capsule adhesions after abdominal trauma.29 If lysis is not performed, it is advisable to record its presence and the patient must been warned, so as not to incur in future diagnostic errors.30,31 Although more infrequent, there are also publications of cases of intestinal obstruction due to these adhesions.32,33

If during a laparoscopy adhesiolysis is performed, great attention must be paid to hemostasis, since when abdominal pressure drops and when the pneumoperitoneum is released, they may begin to bleed.34

The blood test are the usual on PID, that is, leukocytosis with neutrophilia in half of the patients, and frequent elevation of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Determination of antibodies against Chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae can be helpful, while Chlamydia culture is complex and expensive, so we do not usually request it. Liver enzymes and bilirubin are usually normal, or slightly increased.1

When a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance or a Computed Axial Tomography with contrast is performed, subcapsular fluid is usually observed, with hepatic capsule thickening in the arterial phase, secondary to the increase in blood flow caused by the inflammatory process. In 25 % of the patients it is possible to observe the adhesions in “violin strings” fashion, between the hepatic surface and the diaphragm and/or abdominal wall.35,36

Given that the clinical picture of Stajano, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis syndrome usually presents as pain in the right hypochondrium, nausea and vomiting, and few pelvic symptoms, it is not uncommon to be attributed to hepatobiliary pathology, prompting misdiagnosis.1,30,31,37

Antibiotic treatment38 are the same as recommended in PID, and the antibiotics used should be directed following the protocols established by each center, with special emphasis on treating the sexual partner(s).

Stajano, Fitz-Hugh, Curtis syndrome is a rare clinical presentation of upper gynecological infections, characterized by right hypochondrium pain, few pelvic symptoms, and adhesions in a "violin string" form between the liver and the diaphragm or the anterior abdominal wall.

Because the clinical characteristics, the diagnosis is usually delayed or is erroneously made, its usually being assigned to hepatobiliary, appendicular or urological pathology.

The blood test is nonspecific, with a slight leukocytosis with neutrophilia, increased CRP and SED rate. Liver enzymes are usually normal or slightly increased, and sometimes the determination of antibodies against Chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae may help.

It is also not uncommon for “violin string” adhesions to be a surgical finding in an asymptomatic patient. Treatment consists of laparoscopic adhesiolysis, and antibiotic therapy typical of PID.

None.

None.

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

©2022 . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.