eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 4

1Department of Haematology, School of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Nigeria

2Medical Laboratory Science Council of Nigeria, Nigeria

3Federal University Otuoke, Nigeria

Correspondence: Prof. Osaro Erhabor, Department of Haematology, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Nigeria, School of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Nigeria, Tel +447932363217

Received: May 27, 2019 | Published: July 18, 2019

Citation: Osaro E, Abdullahi A, Tosan E, et al. Risk factors associated with malaria infection among pregnant women of African Descent in Specialist Hospital Sokoto, Nigeria. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2019;10(4):274-280. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2019.10.00454

Background: Malaria in pregnancy is a major contributor to adverse maternal and prenatal outcome. In hyper endemic areas like ours, it is a common cause of anaemia in pregnancy and is aggravated by poor socioeconomic circumstance. This study evaluated the socio-demographic risk factors associated with malaria infection among Pregnant Women of African Descent in Specialist Hospital Sokoto, Nigeria.

Main body: A total of 60 consecutively recruited malaria- positive pregnant women participated in the study. Participants were recruited from the antenatal Clinic of Specialist Hospital Sokoto. A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to obtain some socio-demographic characteristics. Data generated was analyzed using SPSS 25.0 statistical package. A p-value≤0.05 was considered significant in all statistical comparisons. The predominant plasmodium specie responsible for all cases of malaria among the subjects was Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria prevalence was compared based on some socio-demographic factors among the subjects. Subjects residing in urban areas were more prone to malaria compared to those living in rural areas (X2=4.957, p=0.026). Pregnant women with no formal education were more predisposed to malaria infection compared to more educated women with primary, secondary and tertiary education (X2=9.040, p=0.029). Pregnant women who did not use insecticide- treated mosquito net was more predisposed to malaria compared to those that do (X2=32.105, p=0.0000). Pregnant women who are not on prophylactic antimalarial medication were more likely to have malaria compared to those that do (X2=18.281, p=0.0000).

Conclusion: This study has shown that Plasmodium falciparum is the predominant malaria specie among plasmodium parasitized women in Sokoto, North Western Nigeria. Socio-demographic factors (residence, illiteracy, non-availability and non -compliance to use of long-lasting insecticide-treated mosquito nets and lack of access to antimalaria prophylaxis during pregnancy) are factors contributing to prevalence of malaria among pregnant African women. There is need to routinely test pregnant women presenting to antenatal clinic particularly with febrile illness for malaria. There is need for the Nigerian government to invest in girl child education and increased awareness about malaria preventive measures, early and regular antenatal clinic attendance as well as universal provision of long insecticide treated mosquito nets and prophylaxis for all pregnant women to reduce the incidence of malaria and its associated morbidities and mortalities.

Keywords: socio-demography, risk factors, malaria, pregnancy, women, African Descent, Specialist Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria

LLINs, long-lasting insecticide-treated nets; IRS, indoor residual spraying; IPTp, intermittent preventive therapy for pregnant women; ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; LLITNs, long- lasting insecticide-treated nets; WHO, World Health Organization; ITNs, insecticide-treated nets; IPTp-SP, intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine during pregnancy; SP, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine

An estimated 30 million women living in malaria endemic areas of Africa become pregnant each year.1 Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to malaria because pregnancy reduces immunity to malaria and increases susceptibility to malaria infection. Pregnant women are three times more predisposed to malarial infection compared with their non-pregnant counterparts, and have a mortality rate that approaches 50%.2

Malaria in pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in the mother, her foetus and the newborn.3 It has several negative including; maternal anaemia, low birth weight, Malaria in pregnancy is associated with severe anaemia, acute pulmonary oedema, renal failure, puerperal sepsis, postpartum haemorrhage and increased risk of death. Malaria in pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as spontaneous abortion, neonatal death, low birth weight, poor development, behavioural problems, short stature, neurological deficits.4

In 2013, there were approximately 198 million cases and 584,000 deaths.5 It was estimated that one death occurs each 30 seconds with 90% of malaria deaths.6 Nigeria is among the 45 countries that are endemic for malaria with a significant 97% of the population being at risk especially children and pregnant women.5

The increased risk of malarial infection among pregnant women has been linked to a number of sociodemographic factors; illiteracy, young maternal age, low educational status, unemployment and low income.7–9

The aim of this study is to investigate the risk factors associated with malaria infection among Pregnant Women of African Descent in Specialist Hospital Sokoto, Nigeria.

Study area

This study was carried out in the Antenatal Clinic of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto, North–Western Nigeria. Specialist Hospital Sokoto is a tertiary institution located within the Sokoto metropolis. Sokoto is the capital city of Sokoto State of Nigeria. The State is located in the extreme Northwest of Nigeria, near to the confluence of the Sokoto River and the Rima River. The State is in the dry Sahel, surrounded by sandy savannah and isolated hills, with an annual average temperature of 28.3˚C (82.9˚F). Sokoto is, on the whole, a very hot area. However, maximum daytime temperatures are for most of the year generally under 40˚C (104.0˚F) and the dryness makes the heat bearable. The warmest months are February to April when day time temperature can exceed 45˚C (113.0˚F). The rainy season is from June to October during which shower are a daily occurrence. Sokoto city is a major commerce center in leather crafts and agricultural products. As at 2006, the state has a population of 3.6 million.10 However, based on the population annual growth of 3%, the calculated projected population for Sokoto State now stands at around 4.9 million.

Study population

The study population for this study includes 60 malaria- infected pregnant women (subject) and 30 age- matched healthy non-parasitized pregnant women who were monitored as controls. Both subjects and controls ware recruited in the Antenatal Clinic of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto, Sokoto North-Western Nigeria.

Study subjects/selection

Inclusion criteria

Women who meet the following inclusion criteria were recruited in the study;

Exclusion criteria

The following were excluded from participating as subjects in the study.

Study design

The research was a case-control study to assess the effect of malaria on some Haematological and Haemostatic Parameters of 60 Plasmodium parasitized pregnant women and 30 age and gender-matched healthy non-parasitized pregnant women were monitored as controls visiting the Antenatal Clinic Specialist Hospital, Sokoto. Blood sample were collected (from both subjects and controls) and tested for complete blood count, Prothrombin Time and Activated Partial Thromboplastin time.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined using the standard formula for calculation of minimum sample size:

n=minimum sample size

z=standard normal deviation and probability.

p=prevalence or proportion of value to be estimated from previous studies.

q=Proportion of failure (=1-P)

d=precision, tolerance limit, the minimum is 0.05.

Therefore, n=z2 pq/d2

Where Z=95% (1.96)

P=6.2% (0.062).11

q=1-0.062 (=0.938)

d=5% (0.05)

Therefore n=(1.96)2 (0.062) (0.938)/(0.05)2

n=88

Study instrument

Questionnaire

A semi- structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was administered to all consenting participants in order to obtain information on their socio-demographic, nutritional and medical history. A sample of the questionnaire is shown in the appendix I.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants (subjects and controls).

Statistical analysis

Data obtained was entered into a statistical package (such as SPSS version 25) on a computer to define the nature of the distribution of data for each group. Statistical differences of data were analyzed using series of statistical analysis such as mean, standard deviation, Chi –square, student’s t-test, ANOVA depending on the nature (categorical or continuous) and distribution of data (normal or non-normal). Pearson’s correlation was used to determine the relationship between sets of data. Probability (p≤0.05) was used to determine the level of significant for all statistical analysis.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Specialist Hospital Sokoto (Reference number: SHS/SUB133/VOL.1 25th May, 2018).

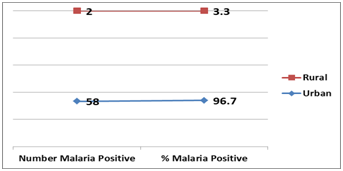

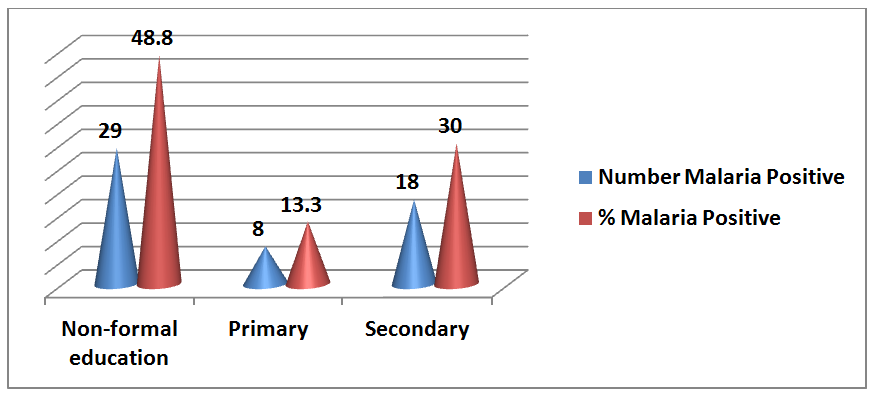

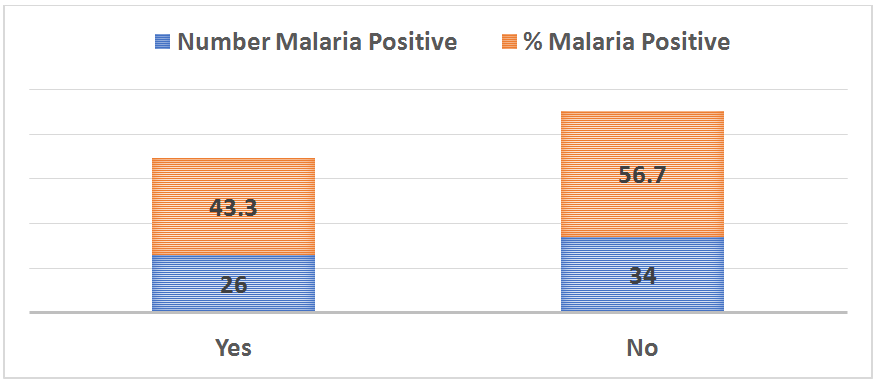

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the Malaria parasitized pregnant subjects and controls. The prevalence of malaria was significantly higher in pregnant women resident in Urban area, those that do not use mosquito net, those that have no non-formal education and those that are not on prophylaxis medication (p<0.05). Age, ethnicity and occupation had no significant effect of the prevalence of malaria among pregnant women (p>0.05). Figure 1 shows the distribution of Malaria parasitaemia based of age. Figure 2 shows the distribution of Malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on ethnicity. The predominant plasmodium specie responsible for all cases of malaria among the subjects was Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria prevalence was compared based on some socio-demographic factors among the subjects. Subjects residing in urban areas were more prone to malaria compared to those living in rural areas (X2=4.957, p=0.026). Figure 3 shows the distribution of Malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on Residence. Pregnant women with no formal education were more predisposed to malaria infection compared to more educated women with primary, secondary and tertiary education (X2=9.040, p=0.029). Figure 4 shows the distribution of Malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on Educational Status. Pregnant women who did not use insecticide- treated mosquito net was more predisposed to malaria compared to those that do (X2=32.105, p=0.0000). Figure 5 shows the distribution of Malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on Occupational Groups. Pregnant women who are not on prophylactic antimalarial medication were more likely to have malaria compared to those that do (X2=18.281, p=0.0000). Figure 6 and Figure 7 shows the distribution of Malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on use of insecticide treated mosquito nets and use of antimalaria prophylaxis respectively. Figure 8: Blood film from one of the subjects showing several ring forms of P. falciparum. Table 1 shows the Socio-demographic characteristics of subjects.

Figure 2 Distribution of malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on ethnicity.

X2=5.370, p=0.068

Figure 3 Distribution of malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on residence.

X2= 4.957, p=0.026*

Figure 4 Distribution of malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on educational status.

X2= 9.040, p=0.029*

Figure 5 Distribution of malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on occupational groups.

X2= 2.432, p=0.296

Figure 6 Distribution of malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on use of insecticide treated mosquito nets.

X2= 32.105, p=0.000*

Figure 7 Distribution of malaria parasitaemia among the subjects based on use of antimalarial prophylaxis.

X2= 18.281, p=0.000*

Variables |

Test (n=60) |

X2 |

p-value |

Age group |

|||

15-20 |

8 (13.3%) |

2.5 |

0.645 |

21-25 |

22 (36.7%) |

||

26-30 |

15 (25%) |

||

31-35 |

11 (18.3%) |

||

36-40 |

4 (6.7%) |

||

Tribe |

|||

Hausa |

57 (95%) |

5.37 |

0.068 |

Fulani |

2 (3.3%) |

||

Yoruba |

1 (1.7%) |

||

Place of residence |

|||

Urban |

58 (96.7%) |

4.957 |

0.026* |

Rural |

2 (3.3%) |

||

Educational status |

|||

Non-formal education |

29 (48.33%) |

9.04 |

0.029* |

Primary |

8 (13.33%) |

||

Secondary |

18 (30%) |

||

Tertiary |

5 (8.33%) |

||

Occupation |

|||

House wife |

52 (86.7%) |

2.432 |

0.296 |

Business |

6 (10%) |

||

Civil servant |

2 (3.3%) |

||

Use of insecticide treated mosquito net |

|||

Yes |

18 (30%) |

32.105 |

0.000* |

No |

42 (70%) |

||

On prophylactic medication |

|||

Yes |

26 (43.3%) |

18.281 |

0.000* |

No |

34 (56.7%) |

|

|

Table 1 The socio-demographic characteristics of subjects

Data are presented as mean±SEM for age and percentages for others.

Key: t, t-test; X2, chi-square; SEM, standard error of mean; *, statistically significant

Malaria is a major public health problem in sub-Sahara Africa including Nigeria, where it accounts for more cases of infection and death than other countries in the world and the extent of utilization of malaria preventive measures may impact on the burden of malaria in pregnancy.12 This study investigated the socio-demographic risk factors risk factors associated with malaria infection among Pregnant Women of African Descent in Specialist Hospital Sokoto, Nigeria.

We observed that younger women in the age group 21-25 years constituted a significant number of the subjects (36.7%) compared to older age group 36-40 (6.7%). This finding is consistent with a previous report by Uneke and Colleagues13 which indicated that individuals of age group 20-24 years had the highest prevalence of maternal malaria (52%) while the least was recorded among those >40 years. Our finding is also in agreement with previous report which indicated that pregnant woman of younger maternal age is at a greatest risk of malaria infection as well as having higher parasite densities.14–17 Several factors may be responsible for this younger maternal age-related predisposition to malaria; general immune suppression and loss of acquired immunity to malaria.18,19

This study has also found that use of insecticide- treated mosquito net has great influence in preventing malaria. Malaria prevalence was significantly higher among women who do not use insecticide treated mosquito nets (p<0.05). This confirms the report of World Health Organization20 on the use of insecticide treated mosquito nets as a means to reduce the lethal impact of malaria. Our finding is consistent with previous reports in Kebbi14 and Calabar21 which indicated the important role that long-lasting insecticide treated nets can play in the prevention of malaria. Our finding collaborates with report by the WHO that the use of ITNs decreases both the number of malaria cases and malaria deaths among pregnant women.22

In this study, the level of education was found to have influence on prevention of malaria in pregnancy. Majority of the malaria parasitized subjects had no formal education (48.3%), this is followed by those who attained secondary level education (30%) then followed by women educated to primary education (13%) and tertiary level education (8.3%) of the subjects. This finding is consistent with previous reports in Karachi, India, Maiduguri, Kebbi Sate and Ondo State Nigeria respectively.14,23–25 This is suggestive that the level of education can play a role in preventing malaria infection.26,27 Our finding is however at variance with a previous report in Lagos which indicated that education was not significantly associated with malaria infection among pregnant women.28

The predominant plasmodium specie responsible for all cases of malaria among the subjects was Plasmodium falciparum. This finding is consistent with previous reports29–34 in Nigeria which found Plasmodium falciparum as the predominant specie responsible for malaria in Nigeria. Mapping the global distribution of malaria motivated by a need to define populations at risk for appropriate resource allocation, and to provide a robust framework for evaluating its global economic impact, has shown that malaria infection particularly caused by Plasmodium falciparum has been geographically restricted and remains entrenched in poor areas of the world particularly in sub Saharan Africa.35

Subjects residing in urban areas were more prone to malaria compared to those living in rural areas (p=0.026). Our finding is consistent with previous reports36,37 which indicated a higher malaria infection in urban compared to rural areas. An evolving major public health challenge seems to be the fact that that urbanization is fast transforming malaria from a rural to an urban disease particularly in poor crowded and rapidly developing urban areas in Nigeria. Several factors promote higher malaria prevalence in urban areas in Nigeria; human migration and the importation of malaria into urban settings, poor housing, suboptimal drainage of Anopheles breeding sites, poor access and use of use of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), poor implementation of indoor residual spraying (IRS), suboptimal implementation of intermittent preventive therapy for pregnant women (IPTp), poor access and use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and inaccessibility to effective treatments using artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT).38–40 Optimal control of urban malaria depends on accurate epidemiologic and entomologic information about transmission.41

We observed in this study that pregnant women who did not use insecticide- treated mosquito net was more predisposed to malaria compared to those that do (p=0.0000). Use of long- lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLITNs) is one of the key components of malaria prevention and control as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).42 The nets reduce human contact with mosquitoes, thus leading to a significant reduction in the incidence of malaria, associated morbidity, and mortality; as well as in the adverse effects during pregnancy in areas of intense malaria transmission.43 Our finding is consistent with previous reports which indicates that the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) for malaria vector control is effective in controlling malaria attacks in pregnant women.44–46 An estimated 27 million ITNs are required annually to effectively protect these most vulnerable groups from malaria infection in Nigeria.47 Unfortunately, few people in high-risk region have access and use ITNs. This is a public health challenge that requires prompt attention. Previous report however indicates that the challenge does not necessarily possess an ITN but low utilization in Nigeria.48

In this study, we observed that pregnant women who are not on prophylactic antimalarial medication were more likely to have malaria compared to those that do (p=0.0000). Our finding is consistent with a previous report49 which suggesting the continuation of IPTp to reduce ppregnancy-associated malaria morbidity. An evidenced based way of controlling malaria in pregnancy is the administration of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine during pregnancy (IPTp-SP). WHO recommends IPTp with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) in all areas with moderate to high malaria transmission in Africa.50 This consists of a full therapeutic course of antimalarial medicine given to pregnant women at routine prenatal visits, regardless of whether they are infected with malaria or not. Intermittent preventive treatment reduces incidences of maternal malaria episodes, maternal and foetal anaemia, placental parasitaemia, low birth weight and neonatal mortality. Evidenced based best practice in Mali of Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with 3 or more doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) has been shown to prevent malaria in pregnant women living in high-risk areas.51 Despite the fact that intermittent preventive therapy in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) is a clinically-proven method to prevent the adverse outcomes of malaria in pregnancy for the mother, her foetus, and the neonates, progress towards implementation of universal coverage remains suboptimal with widespread regional and socioeconomic disparities in the utilization of this highly cost-effective intervention.52

Conclusion

This study has shown that Plasmodium falciparum is the predominant malaria specie among plasmodium parasitized women in Sokoto, North Western Nigeria. Socio-demographic factors (residence, illiteracy, non-availability and non-compliance to use of long-lasting insecticide-treated mosquito nets and lack of access to antimalaria prophylaxis during pregnancy) are factors contributing to prevalence of malaria among pregnant African women. There is need to routinely test pregnant women presenting to antenatal clinic particularly with febrile illness for malaria. There is need for the Nigerian government to invest in girl child education and increased awareness about malaria preventive measures, early and regular antenatal clinic attendance as well as universal provision of long insecticide treated mosquito nets and prophylaxis for all pregnant women to reduce the incidence of malaria and its associated morbidities and mortalities.

None.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interests.

©2019 Osaro, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.