eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 6

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Saint Pauls Hospital Millennium Medical College, Ethiopia

2Department of Biostatistics, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

3Department of Psychiatry, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Delayehu Bekele, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Saint Paulas Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Received: January 05, 2017 | Published: September 8, 2017

Citation: Bekele D, Worku A, Wondimagegn D (2017) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Mental Distress during Pregnancy among Antenatal Care Attendees at Saint Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa. Obstet Gynecol Int J 7(6): 00269. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2017.07.00269

Background: Mental distress (MD) during pregnancy is significant because it has adverse impact on the outcome of pregnancy and may be associated with postpartum depression.

Objective: To determine the prevalence and factors associated with MD during pregnancy among ANC attendees at Saint Paul’s Hospital (SPH)

Methods: A facility based cross sectional study was conducted between December 2012 and March 2013 at the Saint Paul’s Hospital ANC clinic. An exit interview of randomly selected pregnant women in their third trimester attending ANC at SPH was done using a structured questionnaire to determine their socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics and a validated Self-reported Questionnaire (SRQ-20) was used to measure MD.

Results: A total of 753 pregnant women were included in the study. The prevalence MD (SRQ-20 score > 6) was found to be 26.2 %( 95%CI 23.04 -29.36). Women with unplanned pregnancy, with obstetric problems in their current pregnancy and with history of psychiatric illness in the past were found to have a significantly higher MD.

Conclusion: The study revealed that one in four pregnant women have significant MD. Health care providers responsible for ANC must be trained about the relevance and detection of MD during pregnancy. Proper counseling and emotional support should be given for women exhibiting the risk factors.

Keywords: Mental distress, Pregnancy, Antenatal care, Common mental disorders

Pregnancy is generally considered a period of emotional well-being for the woman and her family. However, for many women, pregnancy and motherhood are times of increased vulnerability to psychiatric conditions. Evidences indicate that there is an increase in psychiatric morbidity, particularly the common mental disorders (CMDs) like depression and anxiety, during pregnancy.1

These disorders rob both the woman and her child of the opportunity to enjoy and appreciate some of the most warm, comforting, special moments in each of their lives. Elevated levels of depression and anxiety were also found to be associated with adverse obstetric outcome such as prematurity, low birth weight and fetal growth restriction and had implications for fetal and neonatal well-being and behavior.2-5 If not detected early and managed accordingly these disorders might also evolve into postpartum depression.6

These psychiatric disorders tend to be under diagnosed and often remain untreated because of the overlapping symptoms common to both depression and pregnancy such as changes in appetite, body weight, sleep, libido and energy.7 In addition, comorbid medical disorders like anemia and thyroid dysfunction may cause depressive symptoms and further complicate the assessment of major depression during pregnancy.7,8

Importantly, these disorders are entities that often respond to treatment, both with counseling and/or medications, and it is therefore essential for midwives, primary physicians and obstetricians to understand how prevalent they are and how to appropriately identify and be able to make decisions about treatment and or referral. The early detection and interventions affect both mother and infant, as well as all members of their family.8 Antenatal care provides an optimal time for screening for these psychiatric problems, as pregnant women have frequent contact with healthcare providers.

Most of the studies done on psychiatric disorders during pregnancy in Ethiopia are done on postpartum depression. There are limited number of studies done on the prevalence of ante partum depression and anxiety disorders in general and in urban Ethiopian set up in particular.9-11 This cross sectional facility based study was conducted to contribute in filling this gap and produce a bench mark for further studies on the related subject.

A hospital based study was undertaken between December 2012 and March 2013 at SPH, one of the tertiary referral hospitals in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It was done through an exit interview of pregnant women coming for antenatal care to SPH outpatient department. Pregnant women in their third trimester who volunteer to participate in the study and didn't have any of the exclusion criteria were included. Women in their first trimester were excluded as the symptoms of early pregnancy would be difficult to differentiate from the somatic symptoms included in the assessment of MD. Pregnant women who are on treatment for a psychiatric illness were also excluded. Systematic random sampling method was used to select study subjects from the ANC attendees. A detailed structured questionnaire was used to elicit information on demographic and soci-economic characteristics of participants. Self-reported questionnaire – 20(SRQ-20) was used to measure MD and screen for CMDs was administered by trained psychiatric nurses.

The SRQ -20 tool was developed by the world health organization to screen for psychiatric disturbances in the primary health care setting, especially in developing countries. This 20-item scale asks about depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms present in the preceding one month.12 This tool was preferred for our study because it has been used in previous Ethiopian community-based studies and was extensively pre-validated for use in perinatal the Ethiopian setting.13 The tool was translated to Amharic and then back translated in to English to check for consistency. The study participants were interviewed at exit after completing their clinic visit.

The presence or absence of the twenty anxiety and depressive symptoms in the past four weeks was enquired. A score of “1” was given for a “Yes” response and “0” was given for those who responded “No”. The sum of the score for the 20 symptoms was computed to get the SRQ -20 score of each respondents. Those women who have an SRQ-20 score of six and above were identified as having a MD. A cut-off score of ≥ 6 was taken as it was shown to have convergent validity as an indicator of significant MD and associated with expected predictors of CMD in the Butajira validation study.13

Data was entered and cleaned using Epi info 3.5.4. and analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 statistical package. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review boards of SPHMMC and Gondar University. Permission was obtained from the hospital administrators. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants at all levels. Women who were found to have high SQR-20 score were linked to the psychiatry clinic in the hospital for further evaluation and management.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

Out of the 836 clients who were eligible to this study 753 (90.1%) agreed to participate in the study making the non-response rate 9.9%. As shown in Table 1 the majority of respondents 481(63.9%) were in the age group between 20 and 29. The mean age of the participants was 23.4± 4.75years with an age range of 15 to 42 years. The majority of participants 718(95.4%) were married and more than half of the participants, 426(56.6%) were Orthodox Christians. The other sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

|

Frequency |

Percent |

||

|

Age (years) |

Less or equal to 19 |

27 |

3.6 |

|

20 – 29 |

481 |

63.9 |

|

|

30 – 39 |

237 |

31.5 |

|

|

Greater or equal to 40 |

8 |

1.1 |

|

|

Religion |

Orthodox |

426 |

56.6 |

|

Muslim |

228 |

30.3 |

|

|

Protestant |

91 |

12.1 |

|

|

Others |

8 |

1.1 |

|

|

Ethnicity |

Amhara |

233 |

30.9 |

|

Oromo |

216 |

28.7 |

|

|

Tigre |

45 |

6.0 |

|

|

Gurage |

192 |

25.5 |

|

|

Others |

67 |

8.9 |

|

|

Marital Status |

Married |

718 |

95.4 |

|

Single |

7 |

.9 |

|

|

Widowed |

4 |

.5 |

|

|

Divorced |

12 |

1.6 |

|

|

Non married partner |

12 |

1.6 |

|

|

Educational Status |

Tertiary (diploma and above) |

119 |

15.8 |

|

Secondary (9-12 grade) |

211 |

28.0 |

|

|

Elementary (1-8 grade) |

180 |

23.9 |

|

|

Able to read and write |

108 |

14.3 |

|

|

Illiterate |

135 |

17.9 |

|

|

Estimated Monthly income in Ethiopian Birr |

Less or equal to 799 |

176 |

23.4 |

|

800 – 1199 |

185 |

24.6 |

|

|

1200 – 1999 |

171 |

22.7 |

|

|

Greater or equal to 2000 |

221 |

29.3 |

|

|

Occupation |

Housewife |

471 |

62.5 |

|

Government Employee |

34 |

4.5 |

|

|

Unemployed |

11 |

1.5 |

|

|

Non-governmental Organization |

12 |

1.6 |

|

|

Private Employee |

156 |

20.7 |

|

|

Student |

9 |

1.2 |

|

|

House maid |

2 |

.3 |

|

|

Daily Laborer |

4 |

.5 |

|

|

Merchant |

54 |

7.2 |

Table 1 Socio demographic characteristics of pregnant women attending antenatal care Saint Paul’s

Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, December 2012 to March 2013.

Reproductive history and social support

Table 2 displays the reproductive characteristics of the study participants. One hundred eighty four (24.5%) of the women were primigravidas while 57(7.6%) have a gravidity of 5 and above. A quarter of the women, 192(25.5%) have history of abortion in the past and 48(6.4%) gave history of child death in the past. Most of the women, 626(83.1%) have planned the current pregnancy. Around 10% of the women were told to have an obstetric problem during the current pregnancy. malpresentation was the commonest complication told to the women being present in 38(48.7%) of the 78 women known to have problems during the current pregnancy.

|

Number |

Percent Percent |

||

|

Gravidity |

Primigravid |

184 |

24.4 |

|

II –IV |

512 |

68.0 |

|

|

Greater or equal to V |

57 |

7.6 |

|

|

Parity |

0 |

255 |

33.9 |

|

I –II |

484 |

64.3 |

|

|

Greater or equal to V |

14 |

1.9 |

|

|

Age at first Pregnancy |

13 -16 |

68 |

9.0 |

|

17 -19 |

163 |

21.6 |

|

|

20 -36 |

521 |

69.2 |

|

|

>37 |

1 |

0.1 |

|

|

History of Abortion |

Yes |

192 |

25.5 |

|

No |

561 |

74.5 |

|

|

History of death of Childrens |

Yes |

48 |

6.4 |

|

No |

705 |

93.6 |

|

|

Obstetric Complications |

Yes |

78 |

10.4 |

|

No |

675 |

89.6 |

|

|

Planned Pregnancy |

Yes |

626 |

83.1 |

|

No |

127 |

16.9 |

|

Table 2 Reproductive characteristics of pregnant women attending antenatal care Saint Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, December 2012 to March 2013.

Partner relationship and intimate partner violence

Most women, 690(91.6%) discuss with their husband about their health during the current pregnancy and 686(91.1%) stated that their husband gave them psychological support during the current pregnancy. While 53(7.0%) of the women reported history of ever being beaten by their husbands, only 22(2.9%) of the women reported of being beaten during the current pregnancy. Similarly while 47(6.2%) of the women reported of ever being forced to have sex without their consent, only 32(4.2%) did during the current pregnancy.

Previous psychiatric illness and substance use

Eighteen (2.4%) of the respondents gave history of psychiatric illness which has necessitated evaluation by a health professional. Forty four (5.8%) of the participants take alcohol occasionally, while none take frequently, only two (0.3%) respondents smoke occasionally, one(0.1%) chew Khat frequently and 10(1.3%) chew khat occasionally.

Prevalence of MD and associated factors

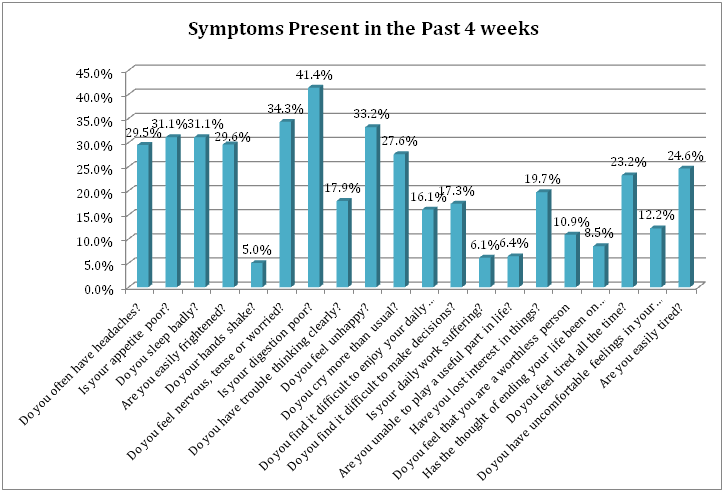

One hundred ninety seven, 26.2% (95%CI 23.04 -29.36) of the respondents have an SRQ-20 score of six and above and were identified to have significant MD. The mean SRQ-20 score of the respondents was 4.25 ± 3.74. The maximum score found was 18 and the minimum was 0. The most commonly present symptoms were poor digestion (41.4%), followed by feeling nervous, tense or worried. The least commonly present symptom was for the question “is your daily work suffering”, 6.1% followed by inability to play a useful part in life 6.4%. The proportion of the respondents with symptoms present in the past four weeks for each of the SRQ-20 questions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Self-reported questionnaire – 20 responses among pregnant women attending antenatal care Saint Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, December 2012 to March 2013.

As shown in Table 3, the prevalence of MD in the age group 20-35 and those who are > 35 years of age was 24.5% and 39.7% respectively. The multivariate analysis of having MD showed that the odds of having a MD was significantly lower in the age group 20 - 35 years as compared to those > 35 years of age with an AOR (95% CI) of 0.51(0.29 -0.91), P- Value = 0 .023.

|

Characteristics |

Mental distress |

Crude OR |

adjusted OR |

||

|

No |

Yes |

||||

|

Age |

< 20 Years |

18(66.7%) |

9(33.3%) |

0.76(.298 -1.94) |

0.58(.18 -1.91) |

|

20 – 34 Years |

497(75.5%) |

161(24.5%) |

0.49(.29-0.83)** |

0.51(.29 -.91)* |

|

|

>35 Years |

41(60.3%) |

27(39.7%) |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

Marital Status |

Married |

542(75.5%) |

176(24.5%) |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

Single |

4(57.1%) |

3(42.9%) |

2.31(0.51-10.42) |

0.99(0.18 - 5.55) |

|

|

Widowed |

1(25.0%) |

3(75.0%) |

9.24(0.96-89.38) |

19.64(1.35-285.07)* |

|

|

Divorced |

5(41.7%) |

7(58.3%) |

4.31(1.35-13.76)* |

1.73(0.43-6.97) |

|

|

Non-married partner |

4(33.3%) |

8(66.7%) |

6.16(1.83-20.70)** |

2.87(.724-11.38) |

|

|

Religion |

Orthodox |

292(68.5%) |

134(31.5%) |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

Muslim |

186(81.6%) |

42(18.4%) |

0.49(0.33 -0.73)*** |

0.535(0.32-.86)* |

|

|

Protestant |

71(78.0%) |

20(22.0%) |

0.61(0.36-1.05) |

0.63(0.34-1.16) |

|

|

Others |

7(87.5%) |

1(12.5%) |

0.31(0.04-2.56) |

0.27(0.012-3.88) |

|

|

Educational Level |

Tertiary |

85(71.4%) |

34(28.6%) |

1.00 |

|

|

Secondary |

152(72.0%) |

59(28.0%) |

0.97(0.59-1.6) |

|

|

|

Elementary |

142(78.9%) |

38(21.1%) |

0.67(0.39-1.14) |

|

|

|

Read & write |

80(74.1%) |

28(25.9%) |

0.88(0.49-1.57) |

|

|

|

Illiterate |

97(71.9%) |

38(28.1%) |

0.98(0.57-1.69) |

|

|

|

Monthly Income (ETB) |

< 799 |

109(61.9%) |

67(38.1%) |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

800 – 1199 |

139(75.1%) |

46(24.9%) |

0.54(0.34-0.85)** |

0.59(0.36-0.97)* |

|

|

1200 – 1999 |

159 (86.4%) |

25(13.6%) |

0.26(0.15-0.43)*** |

0.33(0.19-0.58)* |

|

|

> 2000 |

149(71.6%) |

59(28.4%) |

0.64(0.42-0.99) |

0.73(0.45-1.19) |

|

|

Ethnic Group |

Amhara |

160(68.7%) |

73(31.3%) |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

Oromo |

156(72.2%) |

60(27.8%) |

0.84(0.56-1.27) |

0.91(0.58-1.42) |

|

|

Tigray |

35(77.8%) |

10(22.2%) |

0.63(0.29- 1.33) |

0.68(0.3-1.57) |

|

|

Gurage |

149(77.6%) |

43(22.4%) |

0.63(0.41-0.98)* |

0.84(0.49-1.42) |

|

|

Others |

56(83.6%) |

11(16.4%) |

0.43(0.21-.87)* |

0.74(0.34-1.63) |

|

|

Previous Miscarriages |

Yes |

130(67.7%) |

62(32.3%) |

1.51(1.05-2.16)* |

1.42(0.96-2.11) |

|

No |

426(75.9%) |

135(24.1%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Age at first Delivery |

13-16 |

45(66.2%) |

23(33.8%) |

1.00 |

|

|

17-19 |

122(74.8%) |

41(25.2%) |

0.66(0.36- 1.22) |

|

|

|

20-36 |

388(74.5%) |

133(25.5%) |

0.67(0.39- 1.15) |

|

|

|

>37 |

1(100.0%) |

0(0.0%) |

|

|

|

|

Obstetric Complication |

Yes |

46(59.0%) |

32(41.0%) |

2.15(1.3-3.49)** |

1.97(1.16-3.37)* |

|

No |

510(75.6%) |

165(24.4%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Current Pregnancy Planned |

Yes |

494(78.9%) |

132(21.1%) |

1.00 |

|

|

No |

62(48.8%) |

65(51.2%) |

3.92(2.64- 5.84)*** |

3.64(2.32 - 5.7)*** |

|

|

Ever Beaten |

Yes |

24(75.0%) |

8(25.0%) |

0.94(0.41-2.12) |

|

|

No |

532(73.8%) |

189(26.2%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Beaten during the Current Pregnancy |

Yes |

15(71.4%) |

6(28.6%) |

1.133(0.43-2.96) |

|

|

No |

541(73.9%) |

191(26.1%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Ever forced to have sex |

Yes |

28(75.7%) |

9(24.3%) |

0.90(0.42-1.95) |

|

|

No |

528(73.7%) |

188(26.3%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Forced to have sex during the Current Pregnancy |

Yes |

21(72.4%) |

8(27.6%) |

1.08(0.47-2.48) |

|

|

No |

535(73.9%) |

189(26.1%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Discussion with Husband about Current Pregnancy |

Yes |

529(74.6%) |

180(25.4%) |

1.00 |

|

|

No |

27(61.4%) |

17(38.6%) |

1.85(0.99-3.47) |

|

|

|

Moral Support from Husband |

Yes |

526(74.8%) |

177(25.2%) |

1.00 |

|

|

No |

30(60.0%) |

20(40.0%) |

1.98(1.1-3.58)* |

0.83(0.37-1.84) |

|

|

Parity |

Primiparous |

186(72.9%) |

69(27.1%) |

0.93(0.66-1.31) |

|

|

Multiparous |

370(74.3%) |

128(25.7%) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

History of Child Death |

Yes |

30(62.5%) |

18(37.5%) |

1.00 |

|

|

No |

526(74.6%) |

178(25.4%) |

1.76(0.96-3.24) |

|

|

|

History of Psychiatric Illness |

Yes |

7(38.9%) |

11(61.1%) |

4.64(1.77-12.14)** |

4.04(1.44-11.35)** |

|

No |

549(74.7%) |

186(25.3%) |

1.00 |

|

|

Table 3 Mental distress and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Saint

Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, December 2012 to March 2013.

Statistically Significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

The prevalence of MD among divorced and non-married partners (58.3% and 66.7%) was significantly higher than their married counter parts with a crudes OR of 4.31(1.35-13.76) and 6.16(1.83-20.70). But this association is lost in the adjusted multivariate analysis and the widowed partners have statistical significant positive association with an AOR=19.64(1.35-285.07) and P-value=0.029. But it is worth noting that totally there are only 4 widowed women among the study participants.

Muslims have a prevalence of 18.4% which is significantly lower as compared to orthodox Christians (31.5%), AOR = 5.25(0.32-0.86), P-value = 0.010. Those who have completed elementary school have the least frequency of MD while those who have completed tertiary school have the highest, 28.6% prevalence, but this is not statistically significant.

Those women who were told to have an obstetric problem during the current pregnancy are 1.97 times more likely to have MD as compared to those who were not told, AOR=1.97(1.16-3.37), P-value=0.014. Those who have unplanned pregnancy are also 3.64 times more likely to have MD as compared to those who have a planned pregnancy, AOR=3.64(2.32 - 5.70), P-value = 0.000.

Those women with a previous history of psychiatric illnesses have a higher (61.1%) prevalence of MD as compared to 25.35% in those who doesn’t have. [AOR (95%CI) =4.04(1.44-11.32), P-value = 0.008). The number of Khat chewers, smokers and women who consume alcohol frequently in the study population is small and hence these factors were not included in the bivariate and multivariate analysis.

This study tried to assess the prevalence of significant MD and the associated factors among pregnant women attending ANC at SPH. The prevalence of MD during pregnancy was found to be high with more than a quarter (26.2%) of the pregnant women having a significant level of MD. This prevalence is much higher than the previous study done in Butajira Ethiopia which showed a prevalence of 12%.14 The Butajira study is the best for comparison to our result as it was done using the same tool i.e. SRQ-20 to screen for MD. The high prevalence found in our study might be due to the difference in the data collection process and sociocultural and environmental factors. The Butajira study used female data collectors that have completed secondary school education while our study used psychiatric nurses. The fact that these more experienced psychiatric nurses might be able to pick more women with MD may contribute for the high level of MD found in our study. Other studies also shown that people may be reluctant to acknowledge depressive symptoms to lay interviewers resulting in lower detection.15 The high prevalence might also be a genuine difference and various environmental and socioeconomic stressors present in the urban setting might explain the higher prevalence rate compared to the Butajira study which was conducted predominantly rural set up. The high level of MD during pregnancy in this study calls for further studies to be done in the settings of the urban population. In addition there is a need to further validate different tools which are more specific and enables us to measure the prevalence of the different types of CMDs.

The women in the age group between 20 and 34 has the lowest level of MDAOR. This is consistent with a study done in Bangladesh which has shown similar results.16 Both extreme age’s i.e. teenage pregnancy and pregnancy in the elderly women might be associated with significant psychological distress. The reason might be the physical, psychological, social and economic un-readiness in the teenage pregnancies and fear of poor pregnancy outcomes and the high prevalence of medical and obstetrics problems in pregnancies in the elderly women.

Muslim pregnant women were found to have a significantly lower level of MD as compared to orthodox Christians. This is different from previous studies15 which showed no significant association of mental disorders and religion. Possible differences in between religions in the socio-cultural support structure such as support received from extended family may act as confounders and explain such differences. Studies taking into account such factors should be done in the future as this might reveal important protective factors.

Women who were diagnosed to have obstetric problems during the current pregnancy were found to have a 41.0% rate of MD and this is significantly higher than those who were not told of any problem. This is consistent with the study done in Brazil12 where the prevalence of CMDs was found to be higher in those women with complications during pregnancy than those who don’t have any, with an OR (95% CI) of 1.53(1.10-2.14). Pregnancy in itself is a major experience in women’s life, demanding physiological, psychological and social adjustments, and the presence of additional complications might lead to significant MD in those women who are already vulnerable to CMD. This is an important finding and suggests that health care providers should provide proper counseling and emotional support for those women who are identified to have obstetrics problems during their current pregnancy.

Women with unplanned pregnancy have a 51.2% rate of MD which was found to be significantly higher than those who have a planned pregnancy (21.1%). This is different from the results of previous studies16,17 which hasn’t demonstrated significant association between CMDs and whether the pregnancy is planned or not. But the finding is not surprising and the social and economic burden resulting from the unplanned pregnancies for which adequate preparation was not made might result in psychological distress.

Psychiatric illness in the past has also a strong association with the presence of significant MD. This is consistent with previous studies. In a population based study done in the rural Bangladesh to assess the prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy , it was found that those with a history of mental illness are at an increased risk with an AOR(95%CI) of 4.62(2.72-7.85).16 Similarly in the Brazilian study the prevalence of CMDs was significantly higher among women with a history of previous psychiatric treatment with a prevalence ratio of 1.73 and 95% CI of 1.27 to 2.36.17 These results are inconformity with the general known fact that pregnancy is one of the periods in a woman’s life time when predisposed women for CMDs might develop overt symptoms. Hence health care providers should be vigilant in looking for any subtle evidences of CMDs while providing ANC to those pregnant women with a history of psychiatric illnesses.

The strength of this study is that the data was collected by experienced psychiatric nurses making the study unique from previous studies done in Ethiopia, which used lay interviewers as data collectors. The study is also the first of its kind done in the urban setting in our country which makes it valuable as a base line for future similar studies. But the study has also the following limitation. The sample of pregnant women seeking ANC in a public hospital and may not be representative all other pregnant women including women in the community and those following ANC at a private set up. The cross-sectional nature of this analysis precludes determining causality between the explanatory variables and the outcome.

This study revealed a high prevalence of MD, with one in four pregnant women having a significant MD. This is higher when compared to previous similar studies done in Ethiopia using the same SRQ-20 tool. This indicative of a high burden of CMDs i.e. anxiety and depressive disorders among pregnant women in this urban setting. Those women with unplanned pregnancy, identified and informed to have obstetrics problems during the current pregnancy and previous history of psychiatric illness were found have a significantly higher rate of MD and need proper counseling and emotional support. Primary care health workers responsible for antenatal care must be trained about the relevance and detection of MD during pregnancy.

We would like thank Sister LeifaLadam for coordinating and leading the data collection process, the administration of SPHMMC for allowing us to conduct the study in the hospital. Our greatest acknowledgment goes to all pregnant women who volunteered to participate in the study.

We would like to say special thanks to Dr. Anila Sharma and Dr. Parul Tanwar for providing the histopathology pictures to us.

The authors declare no financial interest or any conflict of interest.

©2017 Bekele, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.