eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 6

Sexological Clinic, Armenia, Quindío, Colombia Armenia Sexological Clinic Quindío Colombia, Colombia

Correspondence: Franklin José Espitia-De la Hoz, Sexological Clinic, Armenia, Quindío, Colombia Armenia Sexological Clinic Quindío Colombia, Colombia, Tel 3127436696, Fax 7459490

Received: November 14, 2019 | Published: December 23, 2019

Citation: Franklin JEDIH. Menopause and sexuality: characterization of sexual dysfunctions during climacteric, in women of Quindío (Colombia). Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2019;10(6):419-424. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2019.10.00477

Gastric cancer, which once was the most common type of cancer, still afflicts a great proportion of the population. There is a tendency towards improving outcomes in regards to mortality, through a greater understanding of tumor biology and particularly its association with Helicobacter pylori infection. However, the 5year survival in general is still poor (20%).

One of the most important areas of opportunity in the treatment of this disease, particularly in high incidence countries and in at risk individuals is early detection of the disease. If this is achieved the individual is a candidate for a diverse set of organ saving interventions which are minimally invasive and achieve excellent long term results.

The purpose of this review article is to analyze endoscopic resection as a treatment for early gastric cancer, describing the two most common techniques: endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), their characteristics and results. Both of them, alone or in a hybrid-modality could be curative in a selected patients with low risk for nodal metastases, without the implications and complications of a gastrectomy. Albeit these are excellent treatment options, there are concerns regarding incomplete resections, lack of expertise, procedural complications and still lack of follow up surveillance criteria. Further research is needed before recommending endoscopic resection as the first line therapy for early gastric cancer.

Keywords: early gastric cancer, endoscopic resection, endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection

EGC, Early gastric cancer; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection

Gastric cancer is the second cause of cancer deaths in both sexes worldwide, producing 738,000 deaths per year.1 However, there is a trend that has been observed during the last 10years towards a decrease in mortality from the disease.2 The cumulative risk of the disease is 2.4% for males and 1.7% for females worldwide. It is currently the fourth most common malignancy in the world (although it was the most common in 1975), 70% of cases occur in developing countries, probably related with the higher prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), with the highest incidence (50% of the total) in Eastern Asia. The male-female ratio is 2:1 in noncardia cancer, but 5:1 in gastric cancer of the cardias.3 Most of the cases are related to H. pylori infection.4 Dietary changes, where populations have better access to fresh fruits and vegetables and the decline in the prevalence of H. pylori is related with the decline in the incidence of gastric cancer.2

Pathologically, cancer is classified in four stages: according to the Tumor Node Metastasis staging system. Where stage I is an early stage which has limited involvement of the wall of the stomach (mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propia) with at most limited lymph node involvement. Stage II is marked by subserosal invasion or extension into visceral peritoneum with or without lymph node involvement. Stage III and IV are more extensive tumors with greater lymph node involvement and spread into adjacent viscera or with distant mets (Stage IV).5

A 5-year survival of 95% is expected if the disease is confined to the inner lining of the stomach wall, but few cancers are diagnosed at this stage.3 In general, the 5-year survival for tumors in stage I is 70%, 30% for stage II, 10% for stage III and 0% for stage IV. Death is more often correlated with metastasis, obstruction and malnutrition.5 A study conducted in Japan in 2015 found a 57% mortality reduction of gastric cancer with endoscopic screening, suggesting its effectiveness.6

The opportune diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer is associated with better prognosis, increased 5-year survival and better quality of life. Thus, this article aims to describe the characteristics of early gastric cancer, its screening, classification and treatment with endoscopic resection comparing techniques and results. Of importance is the fact that gastric cancer screening is cost effective only in areas of high incidence of the disease.

This article is a review article on the literature available on early gastric cancer (EGC) management. With particular attention to the two most prevalent modalities Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), with a brief description of the technique differences, indications, and pitfalls.

EGC is by definition a tumor that invades no more than the mucosal or submucosal layers, with or without lymph node involvement.7

Two main modalities for screening for gastric cancer are upper endoscopy and contrast radiography. Endoscopy has a reported accuracy 90-96%; it allows for direct visualization of the margin of the lesion, visualization of the gastric mucosa, the horizontal extent and depth of tumor also can be measured with standard endoscopic ultrasound and chromoendoscopy. Also endoscopy permits tissue diagnosis permitting identification of precancerous lesions in addition to gastric cancer which may appear as a subtle polypoid protrusion, a superficial plaque, mucosal discoloration, a depression, or an ulcer.8

The second modality is contrast radiography, double-contrast barium imaging with photofluorography can diagnose infiltrating lesions, malignant gastric ulcers and early gastric cancer albeit with a low sensitivity of only 14%. Linitis plastica is the only scenario in which a barium study may be superior to upper endoscopy.9 Other studies have been proposed, but their utility is still unclear. Low serum pepsinogen I and a low serum pepsinogen I/II ratio are suggestive of the presence of atrophic gastritis, a risk factor for gastric cancer. Serum Trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) a small protein in small and large intestine and in gastric intestinal metaplasia, expressed in the goblet cells (sensitivity and specificity 81%), in combination with pepsinogen may provide even higher sensitivity for gastric cancer.10 MicroRNAs: miRNA-421, miRNA 18a, and miR-106a, are detectable in gastric aspirates and in peripheral blood; further studies are needed to establish them as biomarkers for gastric cancer.11

Screening for gastric cancer is controversial, population-based screening for gastric cancer has been implemented in some countries with high incidence of gastric cancer such as Japan, Korea, Venezuela and Chile, in this population, it is recommended for patients greater than 50years old. In areas with low gastric cancer incidence, screening should be reserved for specific high-risk groups, those with gastric intestinal metaplasia, pernicious anemia, gastric adenomas, familial adenomatous polyposis, Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis syndrome. Those patients with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer are not good candidates for screening, because gastric tumors can arise beneath an intact mucosa and elude endoscopic detection; prophylactic gastrectomy should be strongly considered.12–14

Gastric cancers are classified according to both histologic and macroscopic findings. There are important differences between Japanese and Western classifications because Japanese have based the diagnosis on cytological and architectural changes alone, without invasion of the lamina propia and western pathologies require invasion of the lamina propia for the diagnosis. To close the gap, there are some international classifications, such as the Padova international classification of dysplasia15 and the Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia,16 including V categories:

The Lauren classification includes the histopathological characteristics, dividing in two types of lesions: Intestinal Type – tend to form glands, well differentiated, slow growth, and higher incidence in men and more often in older people. Diffuse Type – poorly differentiated, very aggressive and tend to spread throughout the stomach. Same incidence in men and women, but at younger age.17

Macroscopically, one of the most common classification systems is the Borrmann system (Table 1). Type I-polypoid, II- fungating, III- ulcerated and IV- diffusely infiltrating tumors. The Japanese Macroscopic Classification of Superficial Gastric Carcinoma18 is used in Eastern Asia, based on endosonographic features, in particular for indications and outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection. This system includes four types of lesions (Table 1).

Type I (polypoid) |

Ip: pedunculated |

Ips/sp: sub pedunculated |

|

Is: sessile |

|

Type II. Flat lesions |

IIa: superficial elevated |

IIb: flat |

|

IIc: Flat depressed |

|

IIc+IIa: elevated area within a depressed lesion |

|

IIa+IIc: depressed area within an elevated lesion |

|

Type III. Ulcerated lesions |

|

Type IV. Lateral spreading |

|

Table 1 Japanese Macroscopic Classification of Superficial Gastric Carcinoma18

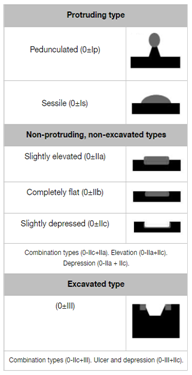

Similar to Japanese classification, the Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions (Table 2). Divided in three groups, Type 0 as polypoid, nonpolypoid or excavated. Type 0-I protruding types, pedunculated or sessile, type 0-II non- protruding and non- excavated types, subcategorized as nonpolypoid type, slightly elevated, flat, and slightly depressed. Type 0-III excavated lesions.19

Table 2 Paris Endoscopic Classification of superficial neoplastic lesions19

Indications for endoscopic resection

Adequate selection of patients for endoscopic treatment of early gastric cancer is the most critical step in the process.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is the process where the lesion is elevated and removed. This technique is minimally invasive and safe. The criteria for selection of patients, who are appropriate for the endoscopic treatment, according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association are:20,21

Endoscopic Submucosal dissection (ESD) is for the complete removal of early gastric carcinoma regardless of its size. Is being used to achieve en bloc resection. Indications of ESD for EGC were expanded, for differentiated type cancers without evidence of lymphovascular invasion. An expansion of these criteria has been propose from clinical observations, to avoid unnecessary surgery.21

Techniques

Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer in two modalities: endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). These techniques have been compared with gastrectomy in many meta-analysis. In selected patients who meet the general indications for endoscopic resection and who have a low risk for nodal metastases, endoscopic resection could be curative. The data suggest similar clinical outcomes when comparing gastrectomy versus endoscopic management in terms of death and recurrence,22,23 with a 5-year overall survival of both over 90 percent.23 However, endoscopic management with ESD or EMR is preferred because of the lower medical costs and shorter hospital stay,22 besides the better quality of life after the procedure if the stomach is preserved.23

The development of metachronous gastric tumor (a second gastric adenocarcinoma or dysplasia detected more than 1 year after ESD or EMR), is one of the major concerns with endoscopic management. The incidence described with endoscopic resection after a long-term period range from 4.3 to 8.5%, compared with 2.4% of incidence after partial gastrectomy.23 Surveillance after endoscopic resection is usually recommended at 6-month intervals during the first year and then annually thereafter. There is still no consensus on a standardized follow-up schedule for the detection of metachronous gastric tumors, but successful treatment of these secondary tumors is possible with repeated endoscopic resection.24 Regardless of approach, it is important to treat H. pylori if there is evidence of infection because its eradication after endoscopic resection has demonstrated a protective effect against metachronous gastric tumors.23

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) are the most studied modalities of endoscopic treatment of EGC. Other modalities include photodynamic therapy, Nd: YAG laser treatment and argon plasma coagulation,25 but this article will focus on the first ones.

EMR consists in the removal of the mucosal lesion from its deeper layers with a snare instrument. Lesions <2 cm can be removed en bloc while larger lesions require piecemeal removal. There are three different methods, most of them described in the 1990s and still performed today. In the injection-assisted EMR, the neoplasia is lifted from the muscularis propria layer with submucosal injections of saline solution26 or 50% dextrose (that lasts longer). Other substances such as: 10 percent glycerol, 5 percent fructose, a fibrinogen mixture, sodium hyaluronate, and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), hydroxyethyl starch 6 percent, have been used. It is recommended that an injection of 20 to 40cc of solution be used to decrease the risk of perforation.27 After the injection an electrocautery snare is used to cut the lesion.

The cap-assisted EMR uses a cap placed at the tip of the endoscope to suck the lesion. A snare loaded previously onto the rim of the cap is pulled after the suction, and the content is resected with high-frequency current. Finally, ligation-assisted EMR uses a standard variceal band ligation device that captures the mucosa and submucosa without muscularis propria due to its contractile force, with subsequent resection with electrocautery snare.26

ESD is a technique that allows en bloc removal of lesions greater than 2cm or flat. The margins should be marked (preferably at 3 to 5mm form the margin) by electrocautery and the lesion can be lifted with submucosal injection. Specialized endoscopic electrocautery knives are required to perform a circumferential incision around the lesion into the submucosa.27 The lesion is then dissected from underlying deep layers with this knife carefully, avoiding incising the superficial dysplastic tissue and the deep layer of muscularis propria.28 A hybrid technique has been described, in which ESD is performed with partial submucosal dissection, with subsequent EMR snare resection, decreasing the complications of ESD alone.29

Different researchers have compared EMR versus ESD. Different meta-analysis have concluded that ESD has a superior efficacy but higher complication rate regarding EMR.30,31

They have found that mean intervention time was longer for ESD but also the en bloc and histologically complete resection rates were significantly higher in this group, leading to lower recurrence rates, compared with the higher risk of recurrence with the piecemeal resection in EMR. However, perforation rate was significantly higher after ESD with respect to EMR. Both techniques had similar bleeding incidences (Table 3). There are several retrospective cohort studies that have reported greater success when ESD is performed in early gastric cancer, likely to result in higher complete resection rates (93 versus 34%) with a recurrence free survival at five years of 100 versus 83% respectively.32

Feature |

Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: A meta-analysis30 |

Long-term clinical efficiency and Perioperative safety of Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus Endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: an updated Meta-analysis |

En bloc resection rate |

Significantly higher for ESD with OR =9.69 |

Higher in the ESD group than in the EMR group (OR =0.01) |

Histological complete |

Significantly higher for ESD with OR = 5.66 |

Higher in the ESD group than in the EMR group (OR =0.14) |

Reccurence rate |

Significantly lower for ESD with OR = 0.99 |

Lower in the ESD group than in the EMR group (OR =37.83 |

operation time |

Significantly lower for ESD |

ESD group was associated with longer operative time than |

perforation rate |

Significantly higher for ESD with OR =4.67 |

Higher the EMD group than EMR group (OR=0.37) |

Bleeding rate |

Significantly higher for ESD with OR =1.49 |

No statistical difference was seen with respect to postoperative |

Table 3 ESD versus EMR

ESD treatment in early cancer showed a curative resection in 88.1% of patients and complete en bloc resection in 98.9%. Non-curative resection where associated with bigger lesions, localized in upper half of stomach and ulcerated lesions. Characteristics associated with successful resections where distal lesions, non-ulcerated, smaller than 20mm. A lesser probability of successful treatment (up to 40% of failure) was found in a proximal, ulcerated, bigger than 30mm.33 Other factors related with non-curative endoscopic resection are female sex, lesion size greater than 2cm, longer procedure time, nodularity, depression and undifferentiated carcinoma. The identification of these factors may help in improve the efficacy of the endoscopic resection in the treatment of ECG with better patient selection.34

The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline of 2015 recommends ESD as a first treatment option for all early gastric cancers with an exception for small (<10mm), Paris 0–IIa lesions in which EMR could be considered.23

Today, the endoscopic resection is a first-line treatment for selected patients with early gastric cancer, with several advantages over total gastrectomy. However, the outcomes still depend on the expertise of the center,33 the accurate selection of patients, the thorough examination of specimen and process of endoscopy and a standardized follow-up strategy.25

We believe both EMS and ESD have won a place in the treatment of early gastric cancer. It is necessary for the patient to have an adequate pre operative evaluation as this is a critical part of the success of the procedure. The results are excellent and allow for patients with this disease stage to have great quality of life after the procedure, with less surgical risk. Albeit follow up has not yet been standardised and there are definitely some potential drawbacks with these limited resections.

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest towards the article.

©2019 Franklin. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.