eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 16 Issue 4

1Jefa de Unidad de Ginecología, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

2Residente Tocoginecología, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

3Médico de Planta de Ginecología, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

4Jefa de Sección Citología, División Anatomía Patológica, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

5Jefe División Ginecología, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

6Jefe de Departamento de Cirugía, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Correspondence: Giselle M Pizarro, Jefa de Unidad de Ginecología, Hospital Juan A. Fernández, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Received: July 07, 2025 | Published: July 21, 2025

Citation: Pizarro G, Correa LM, Alberdi M, et al. Human Papilloma Virus infection in a public hospital in Argentina: prevalence, genotype distribution and atypical cytology in patients with and without HIV infection. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2025;16(3):122-126. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2025.16.00798

Introduction: Screening with human papillomavirus (HPV) testing allows for the evaluation of high-risk virus infection in the cervix, constituting a tool for the prevention of cervical cancer. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a cofactor for persistent HPV infection.

Objectives: To compare the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in patients with and without HIV infection. To evaluate the distribution of HPV genotypes and compare the prevalence of abnormal cytology in both populations.

Methods: Retrospective cross-sectional study based on the records of patients seen at the Cervical Pathology Clinic of Fernández Hospital between March 2022 and November 2024. Women aged 30 years or older, not pregnant, screened with HPV testing were included. Those with a history of treatment for cervical intraepithelial lesions were excluded. The population was categorized as “HIV+” and “HIV-.” The prevalence of HPV infection, distribution by HPV genotypes (categorized as 16, 18, multiple, and others -non-16/non-18-), and cytology with atypical lesions (AGC/ASC-H/H-SIL-cancer) were calculated in both groups.

Results: A total of 2,785 patients were included, of whom 93% (n=2,579) were HIV- and 7% (n=206) were HIV+. In the total population, the prevalence of HPV infection was 14.2% (n=396), while in the HIV- population it was 13.2% (n=341) and in the HIV+ population it was 26.7% (n=55) (p<0.00001). No significant differences were found in the distribution of genotypes in both groups: Genotype 16 was detected in 15% (n=8) of HIV+ patients and in 16% (n=55) of HIV- patients (p=0.92). Genotype 18 was not identified in HIV+ patients, but was found in 7% (n=23) of the HIV- group (p=0.06). Coinfection with multiple genotypes was observed in 11% (n=6) of the HIV+ group and in 7% (n=25) of the HIV- group (p=0.51). Other genotypes were found in 75% (n=41) of HIV+ women and 70% (n=238) of HIV- women (p=0.57). Atypical cytological lesions were detected in 27% (n=15) of HIV+ patients and in 16% (n=56) of HIV- patients (p=0.06).

Conclusion: The prevalence of HPV infection was significantly higher in the HIV+ group (26.7% vs. 13.2%, p<0.00001). No significant differences were observed in the distribution of genotypes between the two groups. We observed a trend toward a higher prevalence of abnormal cytology in the HIV+ population.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, human immunodeficiency virus, cervical cancer, women, cytologic lesions, genotypes

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; CCU, cervical cancer; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Cervical cancer (CCU) represents a major public health problem worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of disease is higher due to limited coverage of screening and vaccination programs.1 In 2020, more than 600,000 new cases and 340,000 deaths from CCU were estimated worldwide, reflecting its significant health and socioeconomic impact.2 In Argentina, approximately 4,500 new cases of CCU are diagnosed per year and about 2,500 deaths occur, being the leading cause of death from gynecological cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women.3,4

Persistent infection by the human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly by genotypes of high oncogenic risk, is the main etiological factor in cervical cancer.5–7 It is estimated that about 80% of sexually active individuals will acquire some type of HPV during their lifetime, although in most cases these are transient infections that resolve spontaneously within two to three years.3,5 Among the more than 200 genotypes identified, at least 14 are considered high-risk, the most prevalent being HPV 16 and HPV 18, which are responsible for approximately 70% of cases of cervical cancer.8

Screening by HPV test, implemented as a primary strategy in Argentina since 2011, has proven to be superior to conventional cytology for detecting precancerous lesions, allowing timely intervention.9 Genotyping by real-time PCR (Abbott test) detects DNA from 14 high-risk genotypes, including 16 and 18 in a differentiated manner, and groups the other 12 (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68) into an "other" category. This molecular methodology provides an effective tool for risk stratification and optimization of healthcare resources.10,11

HIV infection significantly modifies the natural history of HPV. Several studies have shown that women living with HIV have a higher prevalence of HPV infection, a lower rate of viral clearance and a higher risk of persistent infection, especially by multiple high-risk genotypes.12–14 This situation translates into an increased incidence and progression of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) and invasive cervical cancer.

At the local level, the Hospital General de Agudos Juan A. Fernández has implemented since 2022 a population screening program with HPV testing as the primary method. This strategy has made it possible to increase the detection of premalignant lesions and improve patient traceability. In this context, the need arose to analyze the characteristics of HPV infection in women with and without HIV diagnosis in our institution, with special interest in the distribution of genotypes and the presence of high-grade cytologic lesions.

Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the prevalence of HPV infection, the distribution of high-risk genotypes and the frequency of atypical cytology in women with and without HIV, contributing with local evidence to a problem of global relevance.

Objectives

A descriptive, retrospective, cross-sectional study was performed by analyzing the medical records and database of the Cervical Pathology Clinic of the Hospital General de Agudos Juan A. Fernández, during the period between March 2022 and November 2024.

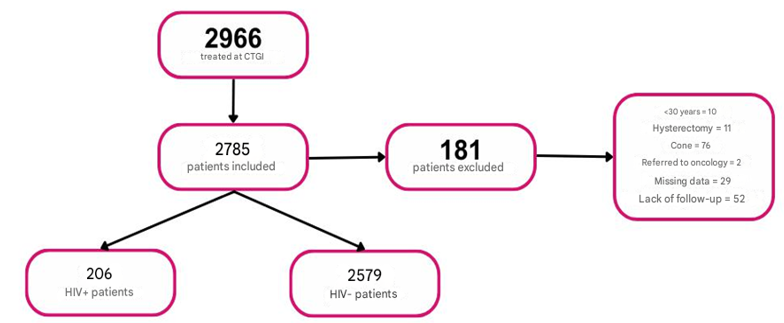

Patients aged 30 years or older, non-pregnant, who were screened with the Abbott test were included. Patients were excluded if they had a history of previous treatment of cervical intraepithelial lesions (cold knife conization, loop diathermy -LEEP-, and laser) or total hysterectomy, regardless of their cause; those who did not continue their follow-up in our institution; and those whose personal and/or medical information was incomplete in the database were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Population included in the study. CTGI: lower genital tract clinic lower genital tract clinic.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; GA, high grade

The population was distinguished according to: smoking history (yes or no); presence of a sexually transmitted infection (yes or no); place of origin (Province of Buenos Aires -PBA- or Autonomous City of Buenos Aires -CABA; parity (multiparous - nulliparous); and health coverage (yes or no).

The screening of the group of interest was carried out using the Abbott test and those with positive results were screened according to the recommendation of the SAPTGIyC guidelines (15) of SAPTGIyC.15

The study population was categorized according to the presence or absence of HIV infection. In both groups, the rate of HPV test positivity was analyzed and, in those with positive results, the HPV genotype of high oncogenic risk found was recorded, categorizing them as: "16", "18", "other" (including genotypes: 31/33/52/58/35/35/39/51/56/59/66/68) and "multiple" (when more than one viral genotype was detected in the same patient).

Regarding the presence of cervical intraepithelial lesions, the following categories were distinguished according to cytologic findings: "negative/L-SIL", "ASC-US/inflammatory", "H-SIL/ASC-H/ACG" and "no results" considered the classification of cytologies based on the classification of Bethesda,16 then accepted by WHO in 2014 and 2020 and presented in Argentina 2016.4

The data obtained were dumped into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and a descriptive and association analysis of the variables was performed using graphs and tables. For statistical analysis, the chi-square test and Fisher's test were used, as appropriate, setting a significance level of p <0.05.

From March 2022 to November 2024, 2966 patients were screened, of which 181 were excluded (10 for being <30 years old, 11 for having a history of total hysterectomy, 76 for having undergone cervical conization, 2 who were referred to the Oncology service, 29 for lack of follow-up in the institution and 29 for incomplete information in the database). Thus, the final analysis included 2785 patients.

The characteristics of the population studied are presented in Table 1. The median age was 48 years (range 30 to 65 years). Sixteen percent (n=409) of the HIV - patients and 32% (n=65) of the HIV + patients were smokers. Thirty-one percent (n=811) of the HIV- and 51% (n=106) of the HIV+ population resided in PBA. On the other hand, 64% (n=2224) of the HIV - and 76% (n=156) of the HIV + patients did not have health coverage. Regarding parity, 86% (n=2224) of the HIV- and 82% (n=169) of the HIV+ patients were multiparous. Finally, 7% (n=168) of HIV- and 38% (n=78) of HIV+ patients had at least one concomitant sexually transmitted infection.

|

Variable |

Category |

HIV + |

HIV - |

|

(n=206) |

(n=2579) |

||

|

Smoking |

Yes |

32% (65) |

16% (409) |

|

No |

68% (141) |

84% (2170) |

|

|

Place of origin |

CABA |

49% (100) |

69% (1768) |

|

PBA |

51% (106) |

31% (811) |

|

|

Health coverage |

Yes |

24% (50) |

36% (933) |

|

No |

76% (156) |

64% (1646) |

|

|

Parity |

Multiparous |

82% (169) |

86% (2224) |

|

Nulliparous |

23% (47) |

14% (355) |

|

|

Transmitted infection sexually |

Present |

38% (78) |

7% (168) |

|

Absent |

62% (128) |

93% (2411) |

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population

In the overall population, the prevalence of HPV infection was 14.2% (n=396) (Figure 2), while in the HIV- population it was 13.2% (n=341) and in the HIV+ population it was 26.7% (n=55, p<0.00001) (Figure 3).

Test positivity rate according to HIV- (n=2579) / HIV+ (n=206).

Regarding HPV genotypes, in both study groups, the most frequent category was "other", with a prevalence of 75% (n=41) in patients with HIV and 70% (n=238) in those without the infection (p=0.57). It was followed by genotype "16", detected in 15% (n=8) of the HIV group and 16% (n=55) of the non-HIV group (p=0.92). Infection with multiple HPV genotypes was the third most frequent, observed in 11% (n=6) of patients with HIV and 7% (n=25) of those without HIV. On the other hand, genotype 18 was not identified in HIV+ patients, but in 7% (n=23) of the HIV- group (p=0.06). No significant differences were found in the distribution of genotypes in both groups (Table 2).

|

Variable |

Category |

HIV + |

HIV - |

p |

|

(n=55) |

(n=341) |

|||

|

16 |

15% (8) |

16% (55) |

0,92 |

|

|

18 |

0% |

7% (23) |

0,06 |

|

|

Genotypes |

Others |

75% (41) |

70% (238) |

0,51 |

|

|

Multiple |

11% (6) |

7% (25) |

0,57 |

Table 2 Distribution of genotypes according to HIV+ (n=55) / HIV- (n=341)

"Others" includes genotypes 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 59, 66 and 68.

Regarding the cytological results found in patients with HPV infection, 71% (n=40) of women with HIV had no cytological lesions or had low-grade lesions (negative/L-SIL). In the HIV-negative group, the proportion was similar at 77% (n=264) (p=0.28). There was a trend towards a higher prevalence of ACG/ASCH/HSIL/cancer cytology in the HIV+ population, which was 27% (n=15) versus 16% (n=56) in the HIV-negative population (p=0.06). Finally, cytologic findings classified as "ASCUS - inflammatory" were detected in 2% (n=1) of HIV patients and 5% (n=19) of those without HIV (p=0.22) (Table 3).

|

Variable |

Category |

HIV + |

HIV - |

p |

|

(n=55) |

(n=341) |

|||

|

Cytologies |

Negative/LSIL |

71% (40) |

78% (264) |

0,28 |

|

ASCUS/inflammatory |

2% (1) |

6% (19) |

0,22 |

|

|

HSIL/ASCH/ACG/Ca |

27% (15) |

16% (56) |

0,06 |

Table 3 Cytological results according to HIV+ (n=55) / HIV- (n=341)

The aim of this study was to analyze the prevalence of HPV infection, the distribution of high-risk genotypes and the frequency of high-grade cytologic lesions in women with and without HIV infection attended at a public hospital in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires.

In our general population, the HPV test positivity rate was 14.2%, a value similar to that reported by the National Ministry of Health in 2021 (12.5%).17 In the group of women with HIV, the prevalence observed (26.7%) was considerably lower than that reported in other studies,18–20 including the one conducted in our hospital in 2024, which resulted in 42%.21 While a higher overall prevalence of HPV was confirmed in women with HIV (26.7% vs. 13.2%; p <0.00001), no statistically significant differences were found in the distribution of genotypes or in the frequency of atypical cytology between the groups compared.

The evidence on the differential distribution of HPV genotypes and their association with premalignant lesions in women with and without HIV is inconclusive. Some multicenter studies show a higher prevalence of types such as HPV 35, 52 and 58 in immunocompromised women, while others find no statistically significant differences between the two groups.22,23 The results of our work showed that the most frequent genotypes in both groups were those included in the "other" category (75% in HIV+ and 70% in HIV-), followed by HPV 16 (15% vs. 16%). HPV 18 was not detected in women with HIV, while it was present in 7% of women without HIV. The distribution was similar to that found in studies conducted in the general population in Argentina and other Latin American countries, where genotypes 16, 52 and 58 predominate in women without HIV.8 For its part, the distribution of HPV genotype prevalence in our population of HIV patients was similar to that reported in the literature, with genotypes 35, 52 and 58 being more frequent, which in our analysis belong to the "other" group and were the most frequently found (75%).12,23 This disparity may be attributed to factors such as the degree of immunosuppression, the use of antiretroviral therapy, access to prevention programs, geographic variability and the type of test used for genotyping.24 In addition, immunosuppression influences the behavior of certain genotypes: for example, some studies suggest that HPV 16 is less affected by the degree of immunosuppression than other oncogenic types, while HPV 18 and 45 may be more associated with difficult-to-detect glandular lesions.25,26

Likewise, no significant differences were found in the prevalence of atypical cytology between women with and without HIV (27% vs. 16%; p = 0.06), despite a trend towards a higher proportion in the HIV-positive group. This lack of statistical significance contrasts with that described in multiple studies that have documented an increased risk of HSIL lesions and invasive cancer in immunosuppressed women.24,25 Immunosuppression conditions a greater persistence of infection and progression to lesions, and African and Latin American studies have found significantly higher prevalence of HSIL in HIV+ women with low CD4 counts.26,27

There are several possible explanations for the absence of statistically significant differences in our findings. First, the small sample size of the HIV-positive group (n=206) may have limited the statistical power of the analysis, especially for detecting differences in subgroups of genotypes or specific grades of lesion. Second, key clinical information such as CD4 count and viral load, factors that modulate the immune response and thus the course of HPV infection, were not included. It is possible that a significant proportion of HIV+ patients were immunologically compensated by effective antiretroviral therapy, which could reduce lesion progression and persistence of high-risk genotypes.

It should also be considered that the "other" category includes 12 high-risk genotypes grouped together without distinction. This limitation prevents us from assessing whether some of these genotypes (such as 35 or 58) are actually distributed differently between women with and without HIV, as suggested by the literature.

Another relevant consideration is that, in studies with a higher proportion of HSIL lesions in HIV+ women, the population evaluated usually has a higher burden of immunosuppression, higher rates of co-infection with multiple HPV types, and lower adherence to follow-up. In our study, it is likely that HIV+ patients had greater adherence to follow-up, with timely diagnosis and treatment of lesions, which may have reduced the progression of HSIL.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective, single-center design and the lack of immunological and virological data in HIV+ women. In addition, the classification of genotypes into broad categories limits comparability with international studies using full genotyping.

In the future, it would be valuable to conduct multicenter studies with greater statistical power, to incorporate immunological and virological data from HIV+ patients, and to include histopathological analysis of lesions. It is also suggested that more specific genotyping tests be used to detect more accurately the differences in viral distribution between the two populations.

Although a significantly higher prevalence of HPV infection was observed in women with HIV, no significant differences were found in the distribution of genotypes or in the frequency of atypical cytologic lesions. These findings highlight the complexity of the interaction between HIV and HPV and the need for further local research to optimize prevention and screening strategies in vulnerable populations.

None.

None.

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2025 Pizarro, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.