eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 6

1Lecturer of Demography and Statistics, African Centre of Excellence in Data Science, University of Rwanda, Rwanda

2Researcher, International Development Studies, Utrecht University, The Netherlands

3Professor of Human Geography and Demography, Utrecht University, The Netherlands

Correspondence: Dr. Ignace H Kabano, Lecturer of Demography and Statistics, Head of Training, African Centre of Excellence in Data Science, University of Rwanda, Po.Box 1514 Kigali, Rwanda, Tel (250)788548640

Received: August 17, 2017 | Published: November 15, 2018

Citation: Kabano IH, Broekhuis A, Hooimeijer P. Effect of inter-pregnancy interval and maternal morbidity on perinatal mortality: a mediation perspective. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2018;9(6):397-403. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2018.09.00374

Objective: To estimate the effect of primigravid status, short and long Inter-Pregnancy Interval effects on perinatal mortality when Maternal Morbidity is mediated.

Study design: 2344 women’s obstetrical files of Kibagabaga District hospital are analyzed. Using a mediation analysis, we estimate the effect of inter-pregnancy interval on maternal morbidity and perinatal mortality.

Result: In contrast to other findings linking IPI length and maternal or perinatal mortality, no significant effect of short IPI is observed in this study. We find a mediation effect of primigravida status and long IPI on perinatal mortality, and a consistent effect of these factors on both maternal morbidity and perinatal mortality.

Conclusion: Findings of this study show a lien between first pregnancies and those conceived after 59 months, and therefore call for more efforts in the improvement of the availability and accessibility of good quality antenatal care and delivery services that are urgently needed, with a special focus on sensitizing primigravid women to use regular antenatal checks.

This study analyses the hypothesized chain of effects of Inter-Pregnancy Interval (IPI) duration on Maternal Morbidity (MM) and subsequent on Peri-Natal Mortality (PNM). Several studies have reported that short and very long IPIs increase the risk of among others small for gestational age, low birth weight and preterm birth, which on their turn relate to a higher risk of perinatal mortality as a culminant outcome.1–5 IPI duration effects as well the health of the mother during pregnancy, and again short and long intervals are found to be harmful for the health status of a pregnant woman and relate to specific maternal morbidity.6,7 Maternal morbidity during the pregnancy on its turn is also associated with pregnancy termination and risks of perinatal mortality.8–10 The above mentioned associations indicate that maternal morbidity is probably a mediator of the relationship between IPI and peri-natal mortality. To analyse this hypothesized chain of effects, this article presents a case study on Rwanda, a small and poor African country where the access of the population to the improved health care system increased remarkably during the last decade. Based on data of 2344 obstetrical files of women who have been treated in the Kibagabaga District hospital located in the capital Kigali, this study explores the direct and indirect effect of IPI duration on peri-natal mortality. As mediators for the measurement of the indirect effect we focused on two types of Maternal Morbidity: Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM) and Third Trimester Bleeding (TTB).

In poor countries perinatal deaths originate, besides from genetic defects of the foetus, from poor maternal health, inadequate prenatal health care, inappropriate management of complications during labour and delivery as well as during the postpartum period.8,9 A foetus or neonate who have endured maternal morbidity during pregnancy, have presumably a greater risk of dying either during pregnancy (stillbirth) itself, or shortly after birth.8,11,12 However, also the reproductive history of the mother could be of influence, in particular the spacing of her pregnancies.

Studies linking IPI and Perinatal or neonatal mortality showed that IPI shorter than 12 months and longer than 59 months are significantly associated with increased risk of adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes.13,14 Main causes behind are low folate and iron for pregnant women, who shortly get pregnant after the outcome of the preceding before recovering from its strains.15,16 Likewise, short IPIs between pregnancies is known to be a driver to maternal morbidity status through the maternal nutritional and folate depletion, incomplete healing of the uterine scar and cervical insufficiency.17 Long IPI could lead to physiological regression, what points at a loss of beneficial physiological adaptations in a woman’s reproductive system that occurs after her first pregnancy. Pregnancy conditions after a long IPI (> 60 months) contain more risks for a woman and resemble the conditions of primigravida. Studies have showed that first pregnancies have also higher risk of experiencing prolonged labour and that of delivering under caesarean section. Besides, this same category of nulliparous women have showed increased risk of antepartum haemorrhage, pregnancy hypertension and low birth weight of the newborn, Intra uterine growth retardation, need to Neonatal Intensive Care and resuscitation, and low neonatal APGAR score with subsequent perinatal mortality.

Most previous studies including IPI duration as an independent variable, focused on these possible relationships between IPI duration and either maternal health and pregnancy outcomes or infant survival. A few studies have however simultaneously linked the effect of IPI on maternal health and pregnancy outcome.10,18,19 Consequently, some possible dual relationships between IPI duration, maternal morbidity or perinatal mortality have been subject of study.

In few previous studies, women with inter-pregnancy intervals of less than 12 months had significantly higher rates of maternal death, hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, puerperal endometriosis, and anemia.1,4,20 In the same way, women with inter-pregnancy intervals of more than 59 months were found to have higher rates of pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational diabetes mellitus. A systematic review of the literature found that long inter-pregnancy interval may be an independent risk factor for pre‐eclampsia and is also associated with increased risk of labor dystocia.13

The premature ruptures of membranes or utero-placental bleeding disorders constitute a high risk for perinatal morbidity and mortality. In the first instance, the premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is associated with brief latency from membrane rupture to deliver, perinatal infection and umbilical cord compression due to a condition in pregnancy characterized by a deficiency of amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios). Women with oligohydramnios in the next stage are more likely to develop chorioamnionitis (inflammation of the membranes that surround the fetus) and sepsis (a bacterial infection in the bloodstream or body tissues) in the newborn, which constitutes a high risk for neonatal mortality.21

The rupture of membranes is associated with placenta previa (which occurs when the placenta is implanted over the internal cervical os) and placenta abruption (which is the premature separation of normally implanted placenta. Both placenta previa and placenta abruption are major causes of antepartum haemorrhage in the third trimester of pregnancies and major contributors of obstetric haemorrhage in general. The effect of these last obstetrical complications on perinatal adverse outcome is related to blood loss of the fetus, the risk of perinatal asphyxia, the risk of sepsis and that of third trimester bleeding.22,23 The effects of IPI become complicated when are combined with that of older or very young age of mothers. In most developing countries’ settings, the socioeconomic status of women combined with the delay in attaining the premises of health care due to either poor infrastructure or health care facilities is more likely prevent women in timely acceding maternal prenatal and delivery care.

The data for this study derives from Kibagabaga District Hospital maternal obstetrical files. This data is used to show specific gestation and delivery complications (morbidities) among 2500 pregnant women who were transferred to Kibagabaga District hospital in Kigali city between 2012 and 2013. These women come mainly from health care centers located in the catchment area of Kibagabaga District hospital, as cases susceptible to severe complications if not clearly monitored by a higher level service delivery unit than a community health care center. The risk of pregnancy-induced illness was identified by the community health care centers’ nurses or midwives along their third trimester visit for antenatal checkup. Among these women, 1054 women, estimated at 42, 7% of all women were primigravid while 156 women did not have complete information on duration between pregnancies, even if they were multi-parous. This last category of women was excluded from the analysis and only 2344 cases remained in the analysis for easy, computation of the Inter-pregnancy Interval.

These files also contained socio-demographic characteristics (age, occupation, province, district, sector and cell, her type of insurance, her reproductive history-number of previous live births, dead and living children, number of previous spontaneous abortions or stillbirths and premature births) of referred pregnant women are registered. The medical history of the mother such as her HIV/AIDS status, the reason of transfer and admission, her medical and surgical history, her last menstrual period and the estimated date of delivery for the subsequent pregnancy are also registered on the hospital files. After the record of women’s medical and reproductive anamnesis, they are admitted and other improved clinical tests are performed to identify the plausible reasons of pregnancy complications and thereafter, a plan is made by the gynaecologist whether to further monitor women on labour, whether to induce the labour or whether to administer caesarean section. At the end of the labour support and before the discharge of the admitted woman, an observation was made and written on her obstetric file, whether the infant was born alive or not, whether the born alive infant was transferred to neonatology due to asphyxia and apnea (breathing problems) and low APGAR scores. Thereafter, it is also written on the file whether the infant died or survived before or after neonatology intervention (mainly reanimation).

On the basis of the above information, this analysis is based on identified pregnancy related illness (Maternal Morbidity) and perinatal mortality for the last pregnancy to control the strength of the independent effect of Inter-pregnancy Interval on these adverse outcomes.

Analytical method definition

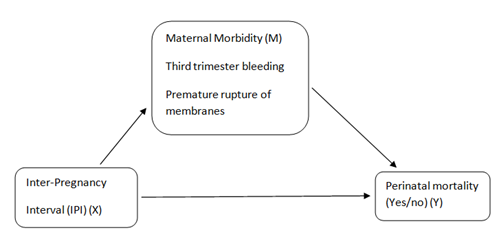

As it has been observed by prior mediation studies, any mediation analysis should evidence causal relationships between the predictor, the mediator and the outcome variables. Thus, an association between the predictor (X: short and Long IPI or Primigravida status in our case) and the mediator variable (M: Maternal Morbidity) is a pre-condition to any mediation study.

Using Andrew F Hayes24 process procedure for SPSS, a simple mediation analysis was performed. Mediation analysis is a statistical method used to help answer the question as to how some causal agent X (IV) transmits its effect on Y (DV) through a single or multiple mediator variables. A simple mediation model is any causal system along which one causal antecedent X variable is proposed as influencing Y through a single intervening Mediator variable (M).

On the basis of the process Method for SPSS as suggested by Andrew F. Hayes, which is a useful computational tool for path analysis-based mediation and its integration into conditional process modelling. The table below illustrates the logic of our model construction on the basis of the process Method (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Relationship between Inter-pregnancy Intervals (IPI)(X), Maternal Morbidity(Mediator) and Perinatal Mortality(Y).

In mediation analysis like in other structural Equations modelling, two or more equations are combined to estimate their effects on the dependent variable. Hence, in the simple mediation analysis, three equations/pathways are suggested in estimating the effect of X on Y. The first relationship goes from X to Y without passing through M(Y=cX+E1) to show the direct effect of X on Y. The second relationship then goes from X to M (M=aX+E2) to distil the effect of X on M to explain the direct effect of X on M. The third relationship passes from predictor X to consequent M and then from antecedent M to consequent Y(Y=bM+c’X+E3). This last relationship constitutes a combined effect of both X and M on Y and is called indirect effect of X on Y through M.

Process also produces estimates of conditional effects direct and indirect effects. The total effect quantifies how much two cases that differ by one unit on X are estimated to differ on Y. The direct effect estimates how much two cases that differ by one unit (higher if c’= +) or one unit (lower if c’= -) on X is estimated to be simultaneously higher and lower on Y. Because in the case of this study X values are dichotomous (Primigravidity(1) versus healthy IPI(0), Short IPI(1) versus healthy IPI(0), Long IPI(1) versus healthy IPI(0)), the direct effect estimated the difference between each critical IPI and healthy IPI means, when the mediator variable(M) is held constant. Given that a coefficient and p-values are provided for both the total and direct effect will be interpreted in reference to the sign of the relationship as well as the significance of p-value. The indirect effect on its part, bootstrapping (which proceeds by constructing a large number of resample of the original sample size N=2344 to B=1000 in our case) is the better inference estimation along which bootstrap confidence intervals provide a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap Confidence Interval.25

Variables definition and operationalization

Dependent variables

Mediation analysis involves more than one dependent variables, be it for simple or for multiple mediation. In this study, maternal morbidity is on one hand a dependent variable when related to Primigravid status and IPI length. On the other hand, maternal morbidity is an intermediate variable while perinatal mortality is dependent variables. Maternal Morbidity was defined by the WHO Maternal Morbidity Working Group as ‘any health condition that is attributed to or aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth that has a negative impact on the woman’s wellbeing’.26 This health condition in this study is measured in terms of two severe obstetrics and delivery complications namely Premature Rupture of membranes and Third trimester bleeding. This mediator-dependent variable was made continuous by moving from not having experienced any of the chosen indicators (PROM and third trimester bleeding), having experienced any or both of them as the second and third category. Perinatal mortality was kept binary with a 0, 1 values. Value 0 standing for having survived after birth and value 1 for having died at Kibagabaga district hospital.

Independent variables

The crucial independent variable is the Inter-pregnancy interval. This category was initially grouped into primigravida, those with IPI of less than 12 months, and those with IPI between 13 and 18 months, those with IPI between 19 and 23 months, those with IPI between 24 months and 59 months and those with IPI from 60 months and higher. IPI between 24 and 59 months was considered to be a healthy IPI in reference to the previous empirical findings. For a better estimation of the effect of IPI on both maternal morbidity and perinatal mortality, IPI was cut into three different dichotomous categories. The first category was made of a binary variable being primigravid (1) versus having spaced the last pregnancy between 24 and 59 months(0), the second category was that of having spaced the last pregnancy to less than 12 months- short IPI(1) versus having spaced the last pregnancy between 24 and 59 months(0) and the last category was that of having spaced the last pregnancy to 60 or more months(1) versus having spaced the last pregnancy between 24 and 59 months(0).

Age of the mother was also controlled for and coded into critical or high risk (those age below 20 and those aged beyond 36 years) (1) versus healthy reproductive age (those aged between 21 and 35 years)(0).

As a proxy to socio-economic status of the mother, the type of health insurance that is used by the parturient mother was considered. In this regards, mothers referred to Kibagabaga hospital without or with a community health insurance were controlled (1) in reference to those with improved health insurance (RAMA, MEDIPLAN, SORAS, UR, etc.)(0). In fact, the structure of the health insurance in Rwanda subdivides insurance beneficiaries according to their occupation and socio-economic status. Most of government employees or those employed by private companies are covered by best insurance schemes covering from 100% to 85% and constitutes roughly 15% of the total population. In the Government of Rwanda’s effort to increase the coverage of health insurance to all Rwandans, a Community Health Insurance was instituted since year 2000. Community Based Health Insurance (CBHI) mechanisms of community financing based on pre-payment and on risk pooling has been very successful in reducing access to health care disparity among Rwandans. The Rwandan Government aims to increase access to health care, including chronic care, for all people. The new CBHI policy was established in 2010 and introduced a system that now provides coverage to over 90 percent of Rwanda’s population. The majority of the insurance system, 55 percent, is paid for through premium payments from the population, with 21 percent of the system covered by the government, 11 percent from donors, and other system fees making up the rest. The poorest citizens, about 25 percent of Rwanda’s population, have now been identified and receive free medical care through CBHI. Referral hospitals also accept the insurance, allowing the poorest citizens with chronic diseases to afford specialized treatment.

The table below presents the characteristics of women that were transferred to Kibagabaga district hospital as a result of obstetrical complications. Among them, 932 (37,2%) were transferred by health centres located in Kigali city, 979 (39,2%) were transferred by those located in rural or peri-urban areas surrounding Kigali city and for 598 (23,6%) women, no referring health care center was mentioned on the hospital discharge files (Table 1).

Covariates |

N=2344 |

Third trimester bleeding |

Premature rupture of membranes |

||

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

||

Inter pregnancy interval (months) |

|||||

IPI(24-59 months)Ref |

395 |

76.2 |

22.8 |

74.2 |

26.8 |

Primigravida |

1054 |

74.9 |

25.1 |

71.4 |

28.6 |

<=12 months |

180 |

79.4 |

20.6 |

77.8 |

22.2 |

13-18 months |

238 |

78.2 |

21.8 |

71.8 |

26.2 |

19-23 months |

267 |

74.9 |

23.1 |

74.2 |

25.8 |

>=60 months |

210 |

70.5 |

29.5 |

67.1 |

32.9 |

Age of the mother at conception |

|||||

(>=21 & <=35 years) Ref |

1888 |

75.7 |

24.3 |

73 |

27 |

(<=20 years) |

421 |

76.2 |

23.8 |

72 |

28 |

(>=36 years) |

191 |

75.4 |

24.6 |

69.6 |

30.6 |

Type of medical insurance |

|||||

(RAMA, MMI, CORAR,MEDIPLAN)Ref |

249 |

74.6 |

25.4 |

72.6 |

27.4 |

(Mutuelle/sante) |

2052 |

75.8 |

24.2 |

72.5 |

27.5 |

(Notspecified) |

43 |

83.7 |

16.3 |

79.1 |

20.9 |

Total/Average |

|

75.8 |

24.2 |

72.6 |

27.4 |

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

The table below summarizes two built in mediation models. The first model presents the effect of Primigravida status, Short and long IPI and confounding factors (age of the mother, type of Insurance) on perinatal mortality in Rwanda. The second model presents a combined effect of Primigravida status, short IPI, long IPI and Maternal Morbidity status on perinatal mortality. The last part of the table summarizes mediation effects of the models.

Effect of primigravida status, short and long IPIs on maternal morbidity (M=aX+E2)

In case of this study, Primigravida status and long IPI have significantly increased the risk of maternal morbidity relatively to women with healthy IPI (between 24 and 59 months after the end of preceding pregnancy), which confirms the existence of the mediation effect in our model. Even though with an expected sign, no significant effect of Short IPI is observed on maternal morbidity. No effect of the age of the mother on perinatal mortality is observed in the model.

The type of health insurance shows on its part an increased risk of maternal morbidity for primigravid poor women without mutual health insurance or with mutual health insurance relatively to their counterparts insured by better health insurances such as RAMA, SORAS, and MEDIPLAN etc. No significant effect of short and long IPI is observed on maternal morbidity (Table 2).

Full Model |

Model 1: Primigravida |

Model 2: Short IPI |

Model 3: Long IPI |

||||||

Outcome 1: Maternal Morbidity |

|||||||||

Coeff |

Sig |

S.E |

Coeff |

Sig |

S.E |

Coeff |

Sig |

S.E |

|

Constant |

0.515 |

*** |

0.045 |

0.506 |

*** |

0.047 |

0.54 |

*** |

0.048 |

Primigravidity |

0.106 |

* |

0.051 |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

Short IPI |

==== |

=== |

==== |

0.016 |

n.s |

0.075 |

==== |

==== |

==== |

Long IPI |

==== |

=== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

0.161 |

* |

0.074 |

Age of the mother (0, 1) |

-0.035 |

n.s |

0.05 |

0.005 |

n.s |

0.092 |

-0.101 |

n.s |

0.089 |

Type health Insurance (0,1) |

0.156 |

** |

0.06 |

0.177 |

n.s |

0.096 |

0.07 |

n.s |

0.096 |

Full Model |

Outcome 2: Perinatal Mortality |

||||||||

Constant |

-4.731 |

*** |

0.448 |

-4.63 |

*** |

0.549 |

-5.091 |

*** |

0.576 |

Maternal Morbidity |

0.465 |

** |

0.151 |

0.469 |

n.s |

0.328 |

0.707 |

** |

0.265 |

Primigravidity |

1.053 |

* |

0.441 |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

Short IPI |

==== |

==== |

==== |

0.595 |

n.s |

0.616 |

==== |

==== |

==== |

Long IPI |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

==== |

1241 |

* |

0.517 |

Age of the mother (0, 1) |

0.306 |

n.s |

0.289 |

0.541 |

n.s |

0.691 |

0.964 |

n.s |

0.511 |

Type health Insurance(0,1) |

0.732 |

* |

0.305 |

0.084 |

n.s |

0.797 |

0.488 |

n.s |

0.596 |

Total, direct and indirect effects |

|||||||||

Effect |

S.E |

Effect |

S.E |

Effect |

S.E |

||||

Total Effect on P M |

1.088 |

* |

1.088 |

0.595 |

n.s |

0.614 |

1.287 |

* |

0.512 |

Direct Effect on P M |

1.053 |

* |

0.441 |

0.595 |

n.s |

0.616 |

1.242 |

* |

0.517 |

Indirect Effect on P M |

0.049 |

0.029 |

0.007 |

0.039 |

0.114 |

0.071 |

|||

BootLLCI = 0.0056; /BootULCI= 0.1271 |

BootLLCI = -0.059; /BootULCI =0.102 |

BootLLCI = 0.0047; /BootULCI= 0.283 |

|||||||

Table 2 Effect of IPI and Maternal Morbidity on Perinatal Mortality in Rwanda

**Significance level: n.s: Not Significant; *<0.005; **<0.01; ***<0.001; =====: not applicable

** Model Summary: Primigravida(R=0.088; Sig: *; F=3.778); Short IPI(Short IPI(R=0.078; Sig: n.s; F=1.171); Long IPI(Long IPI(R=0.099; Sig: *; F=1.196). Abreviation: IPI, Inter-pregnancy Interval

Effect of primigravida status, short /long IPIs and maternal morbidity on perinatal mortality

(Y=bM+c’X+E3)

The constant of this second model outcome is respectively -4.731, -4.630 and -5.091 for Primigravid women, for those who spaced their index pregnancies in less than 12 months and for those who spaced their index pregnancy in 60 or more months. This implies that women who did not experience any premature rupture of membranes and third trimester bleeding during pregnancy, who were not primigravid, who did not space their index pregnancies to less than 12 or to more than 60 months, who were not aged below 20 or more than 36 years, who used an improved health care insurance (RAMA, MEDIPLAN, SORAS etc) have a decreased likelihood of experiencing perinatal mortality. Besides, the second outcome of the mediation model presents the effect of Primigravida status, short and long IPI on one hand and that of maternal morbidity on perinatal mortality on the other hand. As in the first model, primigravida and long IPI also show an increased risk of perinatal mortality. In the same way, maternal morbidity (premature rupture of membranes and third trimester bleeding) show an increased risk of perinatal mortality for both primigravid women and those with IPI longer than 60 months after the preceding pregnancy outcome. Short IPI and age of the mother do not show any significant relationship with perinatal mortality, though bearing an expected positive sign of the relationship. Primigravid women who did not have any or who were insured in the mutual health insurance have also increased the risk of perinatal mortality relatively to their counterparts who used an improved health care insurance. No significant effect is observed on the effect of using community health care insurance or none on perinatal mortality when the latter spaced their index pregnancies to less 12 or to more than 60 months.

Estimation of the total, direct and indirect effects within the models

The total, the direct and indirect effects of the model weigh the strength of the relationship between the antecedent predictor variable (X:IPI); the mediator (M: Maternal Morbidity-Premature rupture of membranes, third trimester bleeding) and the outcome variable (Y: Perinatal mortality).

The total effect is a combined effect of the direct and indirect effect and partitions how differences in the predictor variable are mapped on differences in the outcome variable. Therefore the total effect in the model above shows strong positive effects of Primigravida status and long IPI on Perinatal mortality in Rwanda. The direct effect on its part, explains that one case higher on the predictor variable is subsequently higher on Y. Results of our logit mediation models also shows a strong positive effect of Primigravida status and long IPI on perinatal mortality.

Lastly, the indirect effect is relevant through the existence of a causal inference between the predictor variable(X: IPI) and the mediator variable (Maternal morbidity) on Perinatal mortality. As it was indicated in the first part of the analysis, a significant effect of Primigravida status and Long Inter-pregnancy Interval on maternal morbidity explained a first sine qua none condition for a mediation analysis. However, this is not enough, a conclusive estimation of the strength of mediation effect is to be found in the estimation of bootstrapping with a 95% bias corrected confidence interval. The bootstrap generates the lower and the upper confidence limits of the parameter under estimation. If zero is outside of the lower and the upper limits, then the parameter under estimation is different from zero at 0.05 for a 95% Confidence Interval.

Since the bootstrap estimates do not show any zero in the confidence interval for both Primigravida women (Boot Lower Level CI = 0.0056; /Boot Upper Level CI = 0.1271) and those with long IPI (Boot Lower Level CI = 0.0047; /Boot Upper Level CI = 0.283), a small significant indirect effect of 4,9% for Primigravid women and 11,4% for Long Inter-pregnancy interval. No significant effect is observed for women with short IPI, given that there is a zero indirect effect between lower level (-0.059) and upper level (0.102) confidence interval.

Results of this study indicate three important findings. The first is a significant mediation effect of primigravida status and long IPI through maternal morbidity on perinatal mortality. This effect explains that, a portion of this effect caused by primigravidity status or long IPI after first causing maternal morbidity (premature rupture of membranes and third trimester bleeding) is respectively 4,9% and 11,4%. This motivates the rationale for considering the mediation perspective along the analysis of the effect of Inter-pregnancy interval on maternal morbidity and neonatal mortality. The second is that, besides the mediation effect, that of Primigravida status and Long IPI show consistently the same strong similar patterns on maternal morbidity and perinatal mortality. These similar obstetric complications and perinatal adverse outcome for are self-explained by the fact that in the first instance, primigravid women are known to be a high risk group for experiencing prolonged first and second stage of labour, for increasing the chances of foetal distress during labour and for increasing the risk of either operative vaginal delivery or emergency caesarian section compared to their multiparous counterparts.27 This might be caused by a low physiological orchestration of the maternal stamina to expel the fetus and a lack of responsiveness of the pelvic along the dilation process. In the second instance, previous studies have hypothesized that long IPI are related to the physiological regression status of the mother during the long period between the end of the previous and the index pregnancy. This hypothesis relates to the physiological adaptations of the reproductive system including an increase in blood flow to the uterus in a way that, after an IPI longer than 60 months, the subsequent pregnancy can no longer benefit from these temporary beneficial adaptations and becomes vulnerable as for first pregnancies.1

And thirdly and lastly, no significant effect of short IPI or any significant indirect effect (mediation) is observed on both maternal morbidity and perinatal mortality. In reference to the findings of Habimana I et al.28 & Razzaque,29 short IPIs are associated with high blood pressure. A pregnancy becomes less risky when women under gestational hypertension are properly managed and monitored before it develops proteinuria and pre-eclampsia.

Findings of this study call for more efforts in the improvement of the availability and accessibility of good quality antenatal care and delivery services in Rwanda, with a special focus on sensitizing primigravid women to start antenatal care since the first trimester and use regular antenatal checks. The recent revision of the health insurance scheme intending to group the mutual health insurance within other improved ones such as RAMA, MMI, SORAS AND MEDIPLAN, gives hope that even poor women will accede district hospital for pregnancy and delivery care. This will reduce the proportion of perinatal deaths given the increased adequate antenatal care utilization and will increase deliveries assist by trained attendants in improved standard health facilities.30–38

The weakness of this study lies in two corners. The first is that we use inpatient hospital discharge data, which does not allow the selection a random sample of respondents. It drew a selected sample of women, those who were referred (to) or who simply visited Kibagabaga district hospital, for delivery assistance or who underwent a special treatment after stillbirth by skilled birth attendants as a result of severe complications during pregnancy. The second is that, due to an existing poor filing system at Kibagabaga district hospital, cases considered in this study are those with gynecologic and obstetrical files that were available between 2012 and 2013. A better filing system (may be an electronic filing system) might have allowed us to use a bigger sample and this might have improved the statistical inference and representativeness of delivery-related referred women in Rwanda.

None.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

©2018 Kabano, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.