eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 5

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

2Medical Social Work Department, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

3Reproductive Medicine Department, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

Correspondence: Suzanna Sulaiman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, 100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore, 299899

Received: October 18, 2016 | Published: November 21, 2016

Citation: Sulaiman S, Koon KL, Hassan Y, et al. Clinic for the adolescent pregnant (care) – 5 years on. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2016;5(5):395-398. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2016.05.00172

Introduction: Teenage pregnancy causes both a social and also an obstetrical problem. It not only affects the pregnant mother, but also the baby. Previous studies have showed that dedicated teenage antenatal clinics improve pregnancy outcomes. The Clinic for the Adolescent Pregnant (CARE) was initiated in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Singapore in 2008. This is a dedicated clinic aimed to improve antenatal care for pregnant teenage girls. It focuses on screening for sexually transmitted infections and postnatal contraception with an aim to prevent a second pregnancy.

Methods: A descriptive review of the CARE services from 2008 to 2012 was performed.

Results: CARE has undergone huge improvements in its service provision over the past 5 years since initiation. CARE started with one clinic session every two weekly then increased to two sessions weekly to cater for a growing patient pool. The number of dedicated nurses to counsel teenage pregnant girls on awareness of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and contraception increased. More single teenage pregnant patients are referred directly from various clinics to this dedicated clinic over the years. The monthly multidisciplinary CARE case conference was introduced in 2013 with the intention of improving the ease for multi-disciplinary and holistic management of teenage pregnant mothers.

Conclusion: This study describes the services provided and evaluates the growth experienced in CARE in the past 5 years. CARE will continue to provide holistic care for teenage pregnant girls to help improve pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Teenage Pregnancy, Dedicated antenatal clinic, STI, Contraception

CARE, Clinic for the Adolescent Pregnant; KKH, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital; STIs, Sexually Transmitted Infections; MSWs, Medical Social Workers; PF, Putative Father; FSCs, Family Service Centres

Teenage pregnancy is associated with a multitude of medical and social problems. Teenage mothers were approximately twice as likely to be anemic, have a higher risk of instrumental deliveries and mental health difficulties.1 Teenage mothers also had a higher risk for depression, higher likelihood of living in poverty, and lower likelihood of completing their education relative to peers who delay childbearing.1 Babies born to teenage mothers face a higher risk of preterm birth, which is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.2 They are also at a higher risk of low birth weight, small for gestational age, neonatal and infant mortality.1 An earlier local study in 1989 showed a higher incidence of low birth weight babies among young teenagers especially aged 16 years old and below, largely due to poor intrauterine growth and preterm labour.3

According to the UN Statistics Division, Singapore’s teenage age-specific fertility rate for age 15-19 years old was 7.0 per 1000 women in the period of 2000 – 2005, and 5.0 to 6.0 per 1000 women in the period of 2006-2010.4 The number of teenage births in Singapore to mothers below 19 years old was 781 in 2004 and rose to its height of 853 in 2005.4 It plateaued at 816 in 2008 and subsequently decreased to 575 in 2012.5 There was an increase in sexually transmitted infections from 162 per 100,000 in 1999 to 195 cases per 100,000 in 20036 and the 2 most common Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in 2013 are Chlamydia and Gonorrhoea.7 Teenage pregnancy and its associated problems are a growing problem in Singapore that needs to be addressed promptly.

In a prospective study done by Quinlivan et al.2 in 2004, teenage antenatal clinics for teenage mothers younger than 18 years old were shown to be associated with a reduced rate of preterm birth.2 They hypothesized that this was achieved by preventing ascending genital tract infection and provision of comprehensive teenage specific care. The need for a dedicated teenage antenatal clinic in Singapore led to initiation of the Clinic for the Adolescent Pregnant (CARE).

A descriptive review of the services provided by CARE was done to highlight the services provided by this dedicated teenage pregnancy clinic. Further analysis was conducted in the population of all pregnant adolescents (age<21 at booking visit) who were referred to CARE between January 2008 to December 2012. Data from the clinic registry from January 2008 to December 2012 was obtained for retrospective review. Data on maternal profiling (age at booking, race), postnatal contraception uptake and results of STI screening were collected and analyzed. The pregnant adolescents who were older than 21 years old during booking and lost to follow up were excluded. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption was approved.

Description of CARE clinic and its purpose

CARE is a dedicated teenage pregnancy clinic first set up by the Department of Reproductive Medicine in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) in January 2008. It aims to help pregnant teenage girls cope with their pregnancy, and provide a one-stop centre to deal with the multitude of issues plaguing them (Figure 1). The 2 primary focus of the clinic are firstly, to educate pregnant teenage girls regarding the risk of sexually transmitted infections and also to encourage post-natal contraception to prevent a second pregnancy. Since its implementation 5 years ago, CARE has seen a total of 711 patients up to the end of 2012, amounting to an average of 140 patients per year. Most of the referrals are from polyclinics, specialist clinics and 24 hour Women’s Clinic in KKH, Ministry of Social and Family Development, Pertapis Centre for Women and Children (Islamic Theological Association of Singapore) and other departments within the hospital. The referrals are initiated for single pregnant girls under the age of 21. Service provided by CARE can be divided into 3 subcategories:

Targeted antenatal care: The patient undergoes the initial booking visit in CARE where a screening questionnaire is given to identify risk factors such as smoking or alcohol use. Screening for antenatal depression is also done during the initial visit for early intervention. On top of the routine STI screen done for all antenatal checkups (including Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Syphillis, Hepatitis B virus), CARE also provides additional screening for urine Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhea (Figure 2).

In a review published in 2012 by Allstaff S et al.,8 Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea were two of the few highlighted sexually transmitted infections that have increased incidence in all age groups in the United Kingdom.8 Chlamydia infections can lead to adverse neonatal outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and even neonatal conjunctivitis or pneumonitis in babies born to untreated mothers, while Gonorrhea is associated with increased risk of preterm rupture of membranes, preterm birth and low birth weight. It has also been shown that 40% of women with Gonorrhea are co-infected with Chlamydia.8 Hence, these were chosen to be screened in CARE as they can potentially cause adverse obstetrics outcomes, have readily available treatment, and thus are cost effective as screening tools.

There is a higher incidence of substance abuse in teenage pregnant girls compared to those of the same age who delay pregnancy.1 Hence, referrals to smoking cessation programmes at the booking visit are made to encourage behavioural change during this period of time.

More than 50% of teenage pregnant women were diagnosed with depression in a study done in 2012.9 The study also showed that an increase in social support is associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms. Emotional problems are hence screened for during the booking visit and referrals to trained psychiatrists are made to better manage the patient.

Postnatal care: Contraception counseling is a vital part of the post-natal care provided in the clinic. The study by Quinlivan et al.2 shows a significantly larger number of patients discharged from teenage antenatal clinics with contraception compared to teenage patients in the general antenatal clinic.6 This is important as evidence from a 2-year prospective study has shown that the second pregnancy cements problems such as school dropout, unemployment and poverty.10 As such, the prevention of a second pregnancy and contraception counseling are integral parts of the service provided in CARE.

Holistic care & multidisciplinary approach: Beyond provision of antenatal care, CARE also serves as a one-stop avenue for girls to seek help for other social problems via a multi-disciplinary approach. The Medical Social Workers (MSWs) and nurses in CARE play a vital role in accompanying the teenage girl and her family in the journey through pregnancy and delivery. (Table 1).

|

Duties of the Medical Social Workers (MSWs) in CARE: |

|

1. Psychosocial Assessment of the patient and family |

|

2. Provide emotional and practical support to patient and family |

|

3. Assess Marital Status and Plans |

|

4. Financial Support |

|

5. Link up with local Community Support Services such as: |

|

i. Family Service Centers (FSC) |

|

ii. Beyond Social Services (BABES) |

|

iii. Pertapis Centre for Women and Children |

|

iv. Singapore Girls’ Home |

|

6. Assess Validity of Baby’s care arrangement post delivery |

Table 1 Duties of Medical Social Workers in CARE

CARE carefully monitors the marital status of the girl throughout the pregnancy and discusses issues associated with marriage. Previous studies have shown that children born to unmarried parents may experience more instability in family structure, and this has been linked to negative outcomes for children10. The MSW conducts family conferences with the girl, Putative Father (PF) and respective family members to fully understand the situation. If marriage has been decided, community organizations will step in to initiate marriage counseling. During the course of the counseling, problems such as domestic violence or intimate partner violence are also highlighted and referred to the relevant authorities.

Financial problems are also picked up and referrals to relevant organizations for monetary subsidies are made to deal with the issue. We encourage our patients to return to school or work as it has been shown that if a teenage mother goes on to achieve a high school education,12 the less negative consequences that will be, including a higher risk of a second pregnancy and less income. Other issues such as the living arrangement of the patient and her child are sorted out prior to the delivery. It is important to involve the patient’s family members to provide assistance and optimize the re-integration of the girl back into her original life at school or work.

MSWs serve as the link between these patients, their families and the appropriate support services in the community. They work mainly through the 38 Family Service Centres (FSCs) located in various parts of Singapore. These FSCs offer financial assistance, and run programmes to cater to the needs of the teenage girl. Other collaborating organizations include BABES (Beyond Social Service) and Pertapis Centre for girls and women, Singapore Girls’ Home.

After the delivery, the MSW continues to work with the teenage mothers and community organizations to ensure the accurate and safe placement of the newborn infants. The MSWs would perform home visits to high risk individuals. We ensure the safety of the care arrangement at home, arrange for fostering or adoption through organizations such as Touch Adoption Services by Touch Community Services, as well as Project Cherub by Tanjong Pagar Family Service Centre. There are also private adoption services made available to teenage mothers.

Growth in CARE clinic over the years

There were 678 cases booked with CARE in this 5 year period. 143 records were unavailable as they had been placed with an external party for computerization. 535 cases were available for review. 23 cases were excluded from analysis (3 terminated the pregnancy, 12 were lost to follow up and 8 were 21 years old during delivery). As such, 512 cases were included in the analysis. The average age of the patients during delivery was 17.9 (13-20 years old).

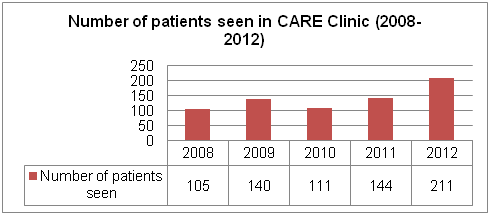

The clinic has expanded, from an initial fortnightly clinic, to a weekly clinic in March 2008, to the current system of having bi-weekly clinic sessions. There is an upward trend in the number of patients seen from 105 in 2008 to 211 in 2012 based on clinic registry figures (Figure 3). The number of dedicated nurse to counsel the girls about STIs and contraception increased from 1 to 2.

Figure 3 Trend of number of patients seen in CARE Clinic from 2008 to 2012 based on the Clinic Registry.

The CARE multidisciplinary Case Conference was first introduced in 2013. It brings together members from various disciplines, including medical doctors, nurses and medical social workers. This conference serves as a platform for inputs to be made from various members of the team for holistic care of the patients.

There is an increase in number of partner community organizations in managing care of our teenage pregnant girls. As of 2013, we are in touch with not only the 38 FSCs located around Singapore, but also other community agencies, shelters and homes to provide help for the patients. The involvement of the Ministry of Social and Family Development, Association of Muslim Professionals and Health Promotion Board is also underway in 2012 as a pilot project to improve care for our teenage girls.

We have seen an increase in the rate of uptake of STI screening services in CARE from 50.0% in 2008 to 85.3% in 2012 (Figure 4). Of those who were screened, an average of 31.0% of them was diagnosed with Chlamydia infection. The rates of Gonorrhoea infections detected were low at 2.2%. The post-natal follow up rate remained constant throughout the years, from 35.4% in 2008 to 41.1% in 2012. 13% of the patients opted for a definitive post-conception contraception method, including oral contraceptive pills and intra-uterine devices.

The increase in number of patients seen in CARE reflects the growing awareness of the clinic in the local setting as it is a referral based system only. However, more work needs to be done to improve its outreach and ensure greater usage of the dedicated teenage antenatal clinic in our community. The introduction of a multi-disciplinary case conference facilitates discussions between healthcare professionals and allied health professionals for individual patients. However, it is still in the initial stage of implementation and may consider involving other medical disciplines to improve antenatal care of these patients.

The increase in uptake of STI screening could be attributed to more in-depth counselling by both doctors and nurses in CARE. The non-invasive mode of sampling via urine specimens may also contribute to the increase in uptake. However, a significant number of patients still decline the screening services. Possible reasons include worries of associated stigmata with a positive result, or cost of test and treatment. It is important to analyze the reasons for declining the screening services in order to improve uptake in future. We note a low uptake of post-conception contraception despite adequate counselling. We recommend further studies to examine reasons for the low uptake of contraception as well as to look for potential solutions to this gap in the CARE services.

The implementation of CARE as a dedicated teenage antenatal clinic in Singapore is an important step forward in the quality of care provision to underprivileged women in our society. The multitude of problems associated with teenage pregnancy brings about great socio-economic impact on our society as a whole, and can be debilitating for the teenage girls involved. There is definitely great potential in the improvements that can be made to CARE, and we seek to not only raise the quality of our care provision by providing a wider range of services but also to further our outreach to the community in future.

No grants were required for this study. Acknowledgement given to staff and patients of CARE clinic over the past few years for contributing to this study.

None.

©2016 Sulaiman, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.