eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Special Issue Novel Ideas in Fertility and Genital Prolapse

Department of Gynecology, Salford Royal Hospital, UK

Correspondence: Sudipta Paul, Consultant Obstetrician & Gynecologist, Freelance author and researcher, Department of Gynecology, Salford Royal Hospital, Salford, UK

Received: August 29, 2016 | Published: September 19, 2016

Citation: Paul S. Bilateral round ligament suspension (RLS) of the vaginal vault during total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) or total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) to prevent post hysterectomy vault prolapse (PHVP) – an innovative surgical technique. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2015;5(2):295-298. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2016.05.00150

Post Hysterectomy Vault Prolapse (PHVP) could happen in 0.2 to 43%. More recently, PHVP has been reported in 11.6% of hysterectomies performed for prolapse and 1.8% for other benign diseases. The frequency of PHVP requiring surgery is between 6-8%. The surgical repairs are effective, however, these are technically complex and are associated with substantial morbidity. Uterosacral and Cardinal Ligaments Suspensions ULS and CLS during abdominal hysterectomy have been suggested to prevent PHVP. Round Ligament Suspension (RLS) of the vaginal vault during abdominal hysterectomy might be useful to prevent PHVP as an alternative/adjunct to ULS and CLS.

N.B. The idea was originally conceived by the author in 1992.

Keywords: PHVP prevention, round ligament vault suspension, RLS

RLS, round ligament suspension; TLH, total laparoscopic hysterectomy; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; PHVP, post hysterectomy vault prolapse; ICS, International continence society; POP-Q, pelvic organ prolapse quantification; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Post Hysterectomy Vault Prolapse (PHVP) could happen in 0.2 to 43% of hysterectomies.1–4 More recently, PHVP has been reported to follow 11.6% of hysterectomies performed for prolapse and 1.8% for other benign diseases.5 Although the incidence of PHVP following abdominal hysterectomy is lower than that of hysterectomies performed for prolapse, it is associated with substantial effects on the quality of life of the women and morbidity in relation to its surgical treatment. The other important issue is that it has occurred in the women who did not have prolapse or at least were not suffering from its symptoms prior to the abdominal hysterectomy. The treatment of PHVP includes surgery, pessary or pelvic floor muscle training.6 A large study from Austria estimated the frequency of PHVP requiring surgical repair to be between 6-8%.7 The surgical repairs are effective, however, these are technically complex and are associated with substantial morbidity. It does increase the already heavy workload of the Urogynecologists further. With the substantial increase in the number of ageing women, the workload of the Urogynecologists has been increasing and is likely to get worse. Therefore, any procedure that might reduce the incidence of PHVP would be useful.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines PHVP as the descent of the vaginal cuff scar below a point that is 2cm less than the total vaginal length above the plane of the hymen.8 The vaginal cuff scar corresponds to point C on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) grid.9

PHVP may occur when the structures that support the top of the vaginal vault are not reattached at the time of the initial procedure or due to weakness of these supports over time. The risk factors for PHVP includes preoperative prolapse [Odds Ratio (OR) 6.6; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.5-28.4], obesity (P<0.001) and sexual activity (OR 1.3; 95% CI 1.0-1.5). Vaginal hysterectomy is not a risk factor when preoperative prolapse is taken into account (OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.5-1.8). Obesity has been reported as the primary risk factor for PHVP following abdominal hysterectomy.5,10 Lukanovic A et al.11 reported that the incidence of vaginal prolapse after hysterectomy was significantly higher in women with a higher number of vaginal deliveries, more difficult deliveries, fewer Caesareans, complications after hysterectomy, heavy physical work, neurological disease, hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse and/or a family history of pelvic organ prolapse. Premenopausal women had surgery for PHVP an average of 16 years after hysterectomy and postmenopausal women 7 years post hysterectomy.11

The case load

Data from the UK suggest a hysterectomy rate of 42/100,000 population, with higher-rates in the United States (143/100,000) and Canada (108/100,000). Countries with no waiting times for surgery have even higher-rates, with Germany reporting rates of 236/100,000 and Australia 165/100,000. The total number of hysterectomies performed in UK NHS hospitals in 2011/2012 was 56,976. Of this, at least 35,396 were abdominal hysterectomies and at least 18,154 were vaginal hysterectomies. The reason for the possible disparity is that it is not possible to break down the overall figure for Scotland, which accounted for 3,426 hysterectomies.12 At an incidence rate of 1.8%, the approximate number of PHVP generated from 35,396 abdominal hysterectomies per year would be about 637. In countries, where the rate and number of abdominal hysterectomies are higher, the number of PHVP would be higher as well.

Surgical treatment of PHVP

The surgical procedures to treat PHVP include vaginal procedures e.g. sacrospinous fixation, high uterosacral suspension, trans vaginal mesh, colpocleisis, and abdominal procedure e.g. sacrocolpopexy that could by done as either open or laparoscopic/robotic procedure. These are effective procedures; however, all of them are associated with significant morbidity. Therefore, a preventive procedure undertaken during abdominal hysterectomy would be beneficial.13–41

Prevention of PHVP following abdominal hysterectomy

Uterosacral ligament suspension, cardinal ligament suspension, Modified McCall culdoplasty etc during abdominal hysterectomy have been suggested to prevent subsequent vault prolapse. These are effective procedures in preventing PHVP. There is no evidence to support the role of subtotal hysterectomy in preventing PHVP.42–47

Description of round ligament suspension of the vaginal vault

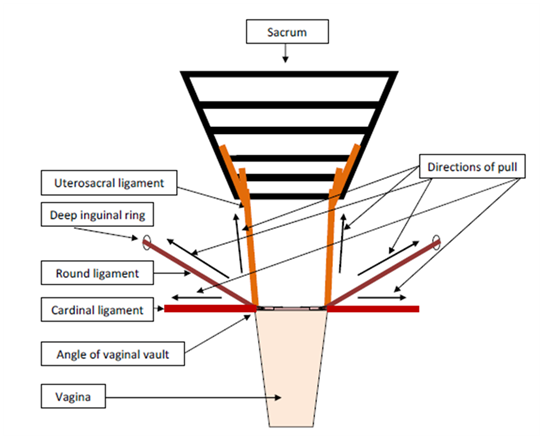

During abdominal hysterectomy ± bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (including laparoscopic total hysterectomy) the round ligaments are divided at about 3 cm from the uterine cornu to keep their lengths adequate. Following hysterectomy, once the vaginal vault is closed, the ends of the round ligaments are attached to the ipsilateral angles of the vaginal vault by No 1 PDS (Polydioxanone II ©Ethicon, US) to suspend the vaginal vault without too much tension. The lengths of the round ligaments on each side should be kept at almost same length so that the vaginal vault is suspended symmetrically to reduce the chance of unequal distribution of traction exerted by the vaginal vault on the round ligaments (Figure 1).

Why Round ligament suspension of the vaginal vault

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of round ligament suspension (RLS), uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS) and cardinal ligament suspension (CLS) of the vaginal vault showing the different directions of pull.

RLS: The round ligaments attached to the angles of the vaginal vault would pull the vault upwards and laterally on both sides in almost opposite directions.

ULS: The uterosacral ligaments attached to the angles of the vaginal vault would pull the vault backwards in almost same direction.

CLS: The cardinal ligaments attached to the angles of the vaginal vault would pull the vault laterally on both sides in opposite directions.

Round ligament suspension of the vaginal vault during abdominal hysterectomy might be a simple and useful procedure to prevent subsequent vault prolapse. It could be used as a separate procedure or as an adjunct to uterosacral and cardinal ligaments suspensions.

None.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interests.

None.

©2016 Paul. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.