eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 5

1Lecturer, Gaston Berger University of Saint-Louis, Gynecology- Obstetrics

2Lecturer, Gaston Berger University of Saint-Louis, Public Health

3Lecturer, University of the Gambia

4Hospital Practitioner, Lieutenant Colonel Mamadou Diouf Hospital of Saint Louis

5Lecturer, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Gynecologist- Obstetrician, Dakar

6Chief Medical Officer of the Saint-Louis Medical Region

Correspondence: Ousmane Thiam, Lecturer, Gynecology-Obstetrics, Gaston Berger University of Saint-Louis, BP 401, Senegal

Received: October 11, 2021 | Published: October 26, 2021

Citation: Thiam O, Niang K, Sow DB, et al. Audit of maternal deaths at the Saint Louis regional hospital from 2017 to 2019. Obstet Gynecol Int J,/i>. 2021;12(5):331-335. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2021.12.00602

Objective: To audit maternal deaths at the regional hospital center of Saint-Louis.

Materials and methods: This was a retrospective cross-sectional study of all maternal deaths that occurred between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2019 at the Saint-Louis regional hospital center. Data were entered on EXCEL 2013 software. Analysis was performed on Epi Info version 3 software.

Results: During our study, 73 cases of maternal death were collected. Maternal mortality was 520 per 100 000 live births. The mean age of the patients was 28.1 years±6.8. Multiparous women accounted for 43.8% and nulliparous women for 1.3%. The causes of maternal death were obstetric hemorrhage (28.77%), hypertension and its complications (20.55%), labour dystocia (15.07%) and anemia (6.85%). Direct obstetric causes of death were responsible for 64.38% of cases and indirect obstetric causes were seen in 35.62%. Death occurred postpartum in 68% of cases, during pregnancy in 25% and during labor in 7%. Death was preventable in 77.5% of cases.

Conclusion: Maternal mortality is a real health problem in our practice. It affects young women. Indirect causes of death are becoming more significant causes of death in our practice. Maternal mortality is avoidable in the majority of cases.

Keywords: epidemiology, mortality, maternal, causes, direct, indirect, audit

Maternal death is defined as "any death of a woman, occurring during pregnancy or within 42 days after its termination, regardless of the duration or site of the pregnancy, from a cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or the care it prompted, excluding any accidental or incidental cause".1 Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is an indicator of the quality of obstetrical care and of the management of parturient women.2

Worldwide, every day, 830 women die from preventable causes during pregnancy, childbirth or the postpartum period.1,2 In 2015, worldwide, 303,000 women died as a result of complications during pregnancy, childbirth, or in the days following.3 Since 1990, the number of maternal deaths has decreased by 44%.3 Currently, almost all maternal deaths (99%) occur in developing countries, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for about 201,000 (66%) deaths.2

West Africa is the most affected, with MMR averaging 564 per 100,000 live births (LBW), compared with 183 in North Africa, 480 in East Africa, 509 in Central Africa and 339 in Southern Africa.2 In Senegal, the maternal death rate decreased from 540 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 273 in 2017.2–4 In the Saint louis’ region, the MMR was estimated at 2100 per 100,000 live births in 2014.5

Despite the efforts made within the framework of the millennium development goals (MDG) and currently, the sustainable development goals (SDG), the mortality rate is still high, which indicates an ineffectiveness or insufficiency of the measures taken. Another strategy has been developed and implemented to further decrease maternal mortality; this strategy is referred to as Surveillance of Maternal Deaths and Responses (SMDR).6–8 This relatively new concept is built on the principles of public health surveillance. SMDR promotes the systematic identification and timely reporting of maternal deaths and is a form of continuous surveillance, linking the health information system and quality improvement processes from the local to the national level.8 It helps to quantify and determine the causes and prevention of maternal deaths. Each of these deaths, which should not have occurred, provides valuable information about appropriate measures that can be taken to prevent future deaths.8

With this in mind, we conducted a statistical review of maternal deaths at the St. Louis Regional Hospital Center from January 2017 to December 2019, with the goal of participating in the reduction of maternal mortality. The overall objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of maternal mortality at Centre Hospitaller Regional de Saint-Louis (CHRSL). The specific objectives were to:

We carried out a retrospective study of all maternal mortalities at the maternity ward of CHRSLfrom January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2019 (36 months). Included in the study were all deceased patients that met the definition of maternal mortality during the study period. All cases that met the WHO definition of maternal mortality during the study period were abstracted from the death register of CHRSL and their medical records subsequently retrieved. We studied sociodemographic data (age, profession, marital status, ethnicity, parity, medical history, prenatal care), clinical data (mode of admission, place and time of death, cause of death and associated co-morbidities, period of death, hospital management, blood transfusion). The outcome of previous maternal death audit sessions was also analyzed. All data were obtained from patient observation records, maternal death registers, maternal death audit forms and obstetric records. We performed data entry on EXCEL 2013 software. Data analysis was performed on Epi-Info version 3 software. For each quantitative variable, the mean and its standard deviation, the median and the extremes were calculated. For qualitative variables, the absolute and relative frequencies were calculated as well as the confidence interval (CI).

Prevalence

Seventy three maternal deaths were recorded during the study period. The number of live births was 14,020 and the total number of deliveries was 14,933. MMR was 520 per 100 000 live births (LB) (Table 1).

|

Years |

Number of maternal deaths |

Number of live births |

Total number of deliveries |

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 LB) |

|

2017 |

26 |

4835 |

5021 |

537 |

|

2018 |

21 |

4435 |

4898 |

473 |

|

2019 |

26 |

4750 |

5014 |

547 |

|

Total |

73 |

14020 |

14933 |

520 |

Table 1 Maternal mortality in CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 t0 2019 (N=73)

Age

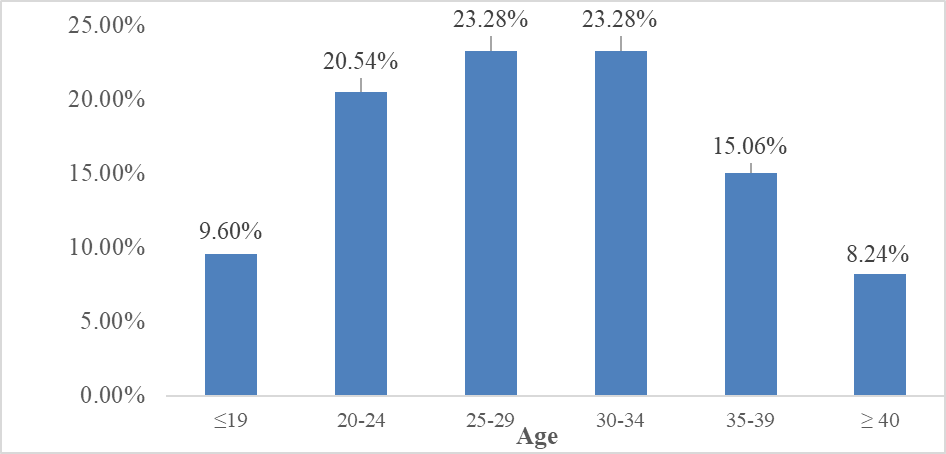

Figure 1 shows the distribution of maternal deaths according to the age at delivery.

Figure 1 Distribution of deaths by patient age range at the CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 to 2019 (N=73).

The mean age of the patients was 28.1±6.8 years. The median was 30 years and the extremes were 16 and 46. Patients aged 20-34 years accounted for more than half of the deaths (67.12%), with 20.54% aged 20-24 years, 23.28% aged 25-30 years and 23.28% aged 30-34 years.

The average parity was 3.73. Multiparous women represented 43.8% against 1.3% nulliparous.

Profession and marital status

Table 2 represents the distribution of maternal deaths by occupation at the CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 to 2019 (N=73). Most of the patients were housewives (81.42%).

|

Profession |

Fréquence absolue |

Fréquence relative (%) |

Total number of deliveries |

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 LB) |

|

Trader |

1 |

1.42 |

5021 |

537 |

|

Student |

2 |

2.86 |

4898 |

473 |

|

Teacher |

2 |

2.86 |

5014 |

547 |

|

House wife |

57 |

81.42 |

14933 |

520 |

|

Others |

11 |

11.44 |

||

|

Total |

73 |

100 |

Table 2 distribution of maternal deaths by occupation

Prenatal care

Table 3 represents the distribution of maternal deaths according to the number of antenatal care (ANC) visits the patient had to the CHRSL maternity ward. The average number of ANC visits was 2.49±1.13. Only 16.47% of cases completed 4 ANC visits and 13.69% of cases did not have any ANC.

|

ANC visits |

Fréquence absolue |

Fréquence relative (%) |

Total number of deliveries |

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 LB) |

|

No ANC |

10 |

13.69 |

5021 |

537 |

|

1 ANC |

10 |

13.69 |

4898 |

473 |

|

2 ANC |

16 |

21.91 |

5014 |

547 |

|

3 ANC |

25 |

34.24 |

14933 |

520 |

|

4 ANC |

12 |

16.47 |

||

|

TOTAL |

73 |

100 |

Table 3 Distribution of maternal deaths by number of prenatal visits to the CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 to 2019 (N=73)

Clinical data

Mode of admission and place of death.

More than half of the patients (56.16%) were referred from other peripheral health facilities, compared with 43.84% who came on their own. Death occurred in 87% of cases in the hospital, 7% at home and 6% during transfer.

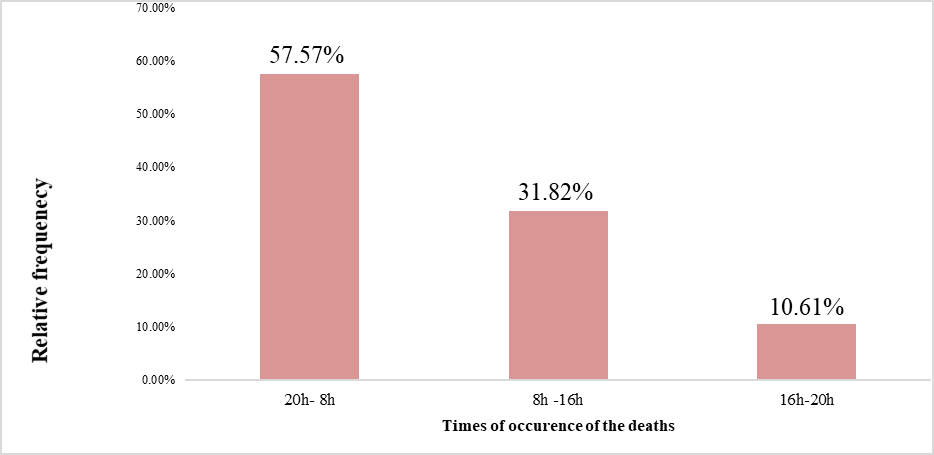

Figure 2 shows the distribution of maternal deaths according to the time of arrival at the CHRSL maternity hospital.

Figure 2 Distribution of deaths by time of occurrence at the CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 to 2019 (N=73).

Death occurred in 57.57% of cases at night between 8:00 pm and 8:00 am, 31.82% of cases in the morning between 8:00 am and 4:00 pm and 10.61% of cases in the evening between 4:00 pm and 8:00 pm.

Pathologies and causes of death

Table 4 represents the distribution of deaths by pathology and cause of death at the CHRSL maternity ward. The causes of death were directed obstetric in 64.38% of cases. Indirect obstetrical causes represented 35.62%.

|

Pathologies and causes of death |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency (%) |

Total number of deliveries |

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 LB) |

|

Hemorrhage |

21 |

28.77 |

5021 |

537 |

|

HTA |

15 |

20.55 |

4898 |

473 |

|

Dystocia |

11 |

15.07 |

5014 |

547 |

|

Anemia |

5 |

6.85 |

14933 |

520 |

|

MTE |

3 |

4.11 |

||

|

HIV & AIDS |

2 |

2.74 |

||

|

Heart disease |

2 |

2.74 |

||

|

Diabetes |

2 |

2.74 |

||

|

Asthma |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Hepatitis |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Severe malaria |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Electrolyte disorder |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Renal disease |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Stroke |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Myocardial infarction |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Pneumothorax |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Cirrhosis |

1 |

1.37 |

||

|

Undetremined causes |

3 |

4.1 |

||

|

Total |

73 |

100 |

Table 4 Distribution of deaths by pathology and cause at the CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 to 2019 (N=73)

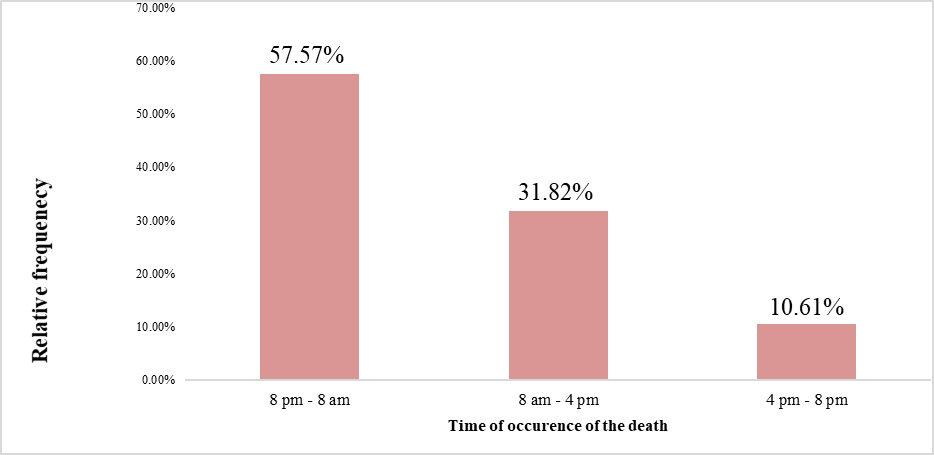

Period of death

Figure 3 shows the distribution of deaths according to the time of the day when the death occurred at the maternity ward of the CHRSL. More than half of all maternal deaths occurred during the night shift from 8 pm to 8 am.

Figure 3 Distribution of deaths by time of death at the CHRSL maternity ward from 2017 to 2019 (N=73).

About 68% of maternal deaths in the study occurred in the postpartum period while 25% or deaths occurred in the prenatal period and 7% occurred during labour.

Maternal death audit

About 77.5% of the maternal deaths were deemed to have been preventable.

Death was preventable

We were confronted with incomplete medical records including antenatal care records as well as undocumented verbal autopsy.

Maternal mortality ratio in our study was 520 per 100,000 live births. There was a significant decrease in MMR compared to 2014 which was 2100 per 100,000 live births.5 This decrease in the prevalence of maternal mortality can be explained by the regular organization of maternal and neonatal death audit sessions. During these sessions, factors that may lead to serious maternal morbidity or mortality are identified and an action plan for solving these problems or challenges are developed. The implementation of the action plan was evaluated on a monthly basis.

Age

Adolescent girls (< 19 years) accounted for 9.6% of deaths. Those over 35 years of age accounted for 23.3%. This data shows that extremes of the reproductive age remain a risk factor for maternal mortality in our practice area. Several situations could explain this excess mortality, the occurrence of early and complicated pregnancies in adolescents with low socioeconomic status, the lack of adequate prenatal care, unwanted pregnancies and late recourse to care. This data is corroborated by several African studies9,10 with similar findings.

Parity

The majority of deaths were among multiparous women (43.8%). This excess mortality of multiparous women reported in our study was similar to the data reported by Diallo AK.11,12 who found 50% in the Kolda Regional Hospital. This can be explained by the fact that these women have a fragile, "glass" uterus with numerous pregnancies and sometimes dysfunctional labour and delivery that may predispose them to uterine atony and uterine rupture leading to postpartum hemorrhage.

Prenatal follow-up

Focused prenatal consultations make it possible to detect risk factors during pregnancy and to provide effective management. To this end, inadequate prenatal care is a risk factor for maternal death. In our study, we noted that more than 13.69% did not have any ANC and nearly 83.53% of patients did not have the standard of 4 ANC visits as set out in the Senegalese Policies, Standards and Protocols.2,5,13–18

Mode of admission

Obstetrical medical evacuations are often superimposed on maternal deaths. Thus, we noted in our study that 56.16% of deaths were referred from other health facilities. This high frequency of maternal deaths among evacuees can be explained by the fact that the maternity ward of CHRSL is the only referral facility for obstetric emergencies in the zone.

Pathologies and presumed causes of death

The presumed causes of death are multiple and varied, most often associated.18,19

Obstetric haemorrhage was the leading cause of maternal death in our series with 28.77%. This is similar to the data reported by Thiam O.12 at the Roi Baudoin Health Center in Guédiawaye which was 30.3%. Several factors may be responsible for this including a delayed referrals from the referring hospitals, parturients referred without an intravenous access, lack of adequate emergency medical transport to the department and lack of a blood bank.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and its complications were the second leading cause of maternal mortality in our study with 20.55%. This is similar to the data reported by Blaise K. T. L. in the gynecology-obstetrics and anesthesia-intensive care departments of the POINT "G" University Hospital in Bamako10 and Diallo AK.16 at the Regional Hospital Center of Kolda (19.17% and 24.2% respectively). This is probably related to the fact that pregnant women were not adequately advised on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and its complications coupled with late presentation from the referring hospitals.

Other causes of maternal mortality in our study are: labour dystocia (15.07%), anemia (6.85%), thromboembolic diseases (4.11%), heart disease (2.74%), HIV / AIDS (2.74%), and the other 19.17% (made up of diabetes, asthma, hepatitis, severe malaria, electrolyte disorders, nephropathy, stroke, myocardial infarction, pneumothorax and cirrhosis). Delay in medical referrals and the paucity of human and material resources to adequately address these conditions are significant factors in all these maternal deaths.

Maternal death audit

At the end of the death audit sessions, 77.5% of cases were preventable. Diallo AK.16 and Coulibaly Z20 reported 70% in the Kolda Regional Hospital, 63.6% in the District of Bamako, and 78.72% in the gynecological-obstetrical department of the Sikasso Hospital in Bamako.

Death was preventable during the initial examination of the patients in 26.82% of cases, during diagnosis in 11.92% of cases and during treatment in 38.75% of cases.

Our study affirms that maternal mortality is a real public health problem in our obstetric practice. It occurs in young married multiparous women with low socioeconomic status often following referral from another hospital. It occurs in the immediate postpartum period and obstetric hemorrhage is a significant cause. In light of these findings, we make the following recommendations:

None.

None.

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

©2021 Thiam, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.