eISSN: 2377-4304

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 6

1Departments of Pathology & Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University

2Departments of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University

Correspondence: Shinichi Aishima MD PhD, Departments of Pathology & Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Nabeshima5-1-1, Saga City, Saga, Japan 849-8501, Tel 81-952-34-2234, Fax 81-952-34-2055

Received: October 30, 2020 | Published: November 11, 2020

Citation: Fukushima SMD, Nakayama YMD, Hanashima KMD, et al. A case of ovarian carcinosarcoma composed of endometrioid carcinoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2020;11(6):338-340. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2020.11.00534

Ovarian carcinosarcoma (OCS) is a rare malignancy accounting for only 1‒4% of all ovarian cancers. A 44-year-old premenopausal woman presented at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the University Hospital of Saga, with the chief complaint of sudden abdominal pain. Tumor markers present in her serum were cancer antigen (CA) 19-9 (103U/mL), and CA 125 (114U/mL). Transvaginal ultrasound examination showed a complex mass (74×71×67mm) with solid and cystic components in the left abdominal area. Abdominopelvic computed tomography images showed a polycystic mass with a long diameter of 94 mm in the left adnexal area. The patient underwent a laparotomy immediately after the appropriate evaluation of examinations, leading to total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and partial omentectomy. Due to the emergency surgery, intraoperative histological diagnosis for ovarian tumor was not performed. The preoperative evaluation of radiological imaging revealed no evidence of lymph node swelling, therefore lymph node resection was omitted. The left ovarian tumor already showed a partial rupture. Pathological examination following surgery revealed tubular and solid growth of the epithelial component and fascicular growth of spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells. Immunohistochemistry identified the epithelial component as endometrioid carcinoma (EC) and the mesenchymal component as endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS). Endometriotic tissue was attached to the malignant tumor. The patient was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (paclitaxel plus carboplatin) after surgery. The patient is still alive without recurrence at 9 months after surgery. Considering the rarity of OCS with EC and ESS, we present an overview of the literature and discuss several histological and clinical issues. The etiology and pathogenesis of such tumors require further investigation (words; 228).

Keywords: ovarian carcinosarcoma, endometrioid carcinoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, treatment

OCS, ovarian carcinosarcoma; EC, endometrioid carcinoma; ESS, endometrioid stromal sarcoma

Ovarian carcinosarcoma (OCS) is a rare malignancy accounting for only 1-4% of all ovarian cancers.1 OCS has been associated with higher rates of metastatic disease and poor prognosis when compared with other subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer.

By definition, OCS contains both malignant epithelial and sarcomatous elements. The epithelial component is often serous, endometrioid, undifferentiated carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. The malignant mesenchymal component is described as homologous or heterologous. Homologous elements (indigenous to Mullerian structures) resemble endometrial stromal sarcoma, fibrosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma. If the sarcomatous part contains elements not normally found in the Mullerian structures (e.g., cartilaginous, osseous, or rhabdomyoblastic elements), then it is described as heterologous.2 The epithelial and mesenchymal elements in these tumors are usually randomly admixed with one another. Both are high-grade, but the mesenchymal component occasionally can be composed of relatively bland spindle cells. Immunohistochemistry helps to identify epithelial or mesenchymal elements in cases of nondescript, indeterminate morphology.3 There is no standard opinion on the optimal treatment for OCS.

Patient and clinical diagnosis

A 44-year-old premenopausal woman presented at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the University Hospital of Saga with the chief complaint of severe pain in her lower abdomen.

She had never been pregnant and her menstrual cycle was regular, but with menstrual pain. She had a 9-year medical history of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), which had been followed by another hospital, and right ovarian chocolate cysts, excised by laparotomy 11years ago. She had no history of fever, dysuria, diabetes, or weight loss. Superficial lymph nodes were non-palpable.

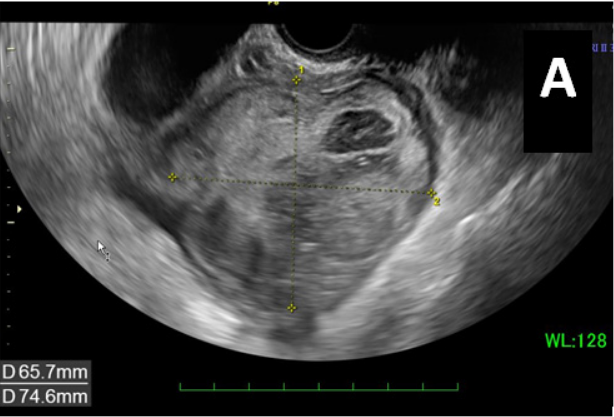

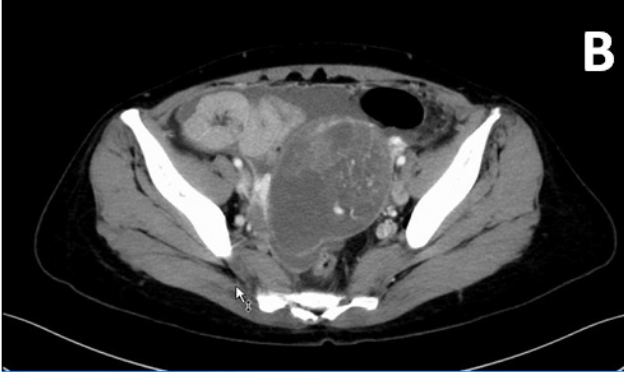

The patient was checked immediately after admission to the hospital. Liver function showed an AST of 38U/L, ALT of 59U/L, and G-GT of 397 U/L. Coagulation testing showed a fibrinogen level of 425.2mg/dL and D dimer level of 10.63mg/dL. Her kidney function test and chest x-ray showed no specific findings. She had two elevated serum tumor markers: cancer antigen (CA) 19-9, 103U/mL (normal range 0-37), and CA 125, 114U/mL (normal range 0-35). The level of the other marker was within the normal range: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), 2.3U/mL (normal range 0‒37). A transvaginal ultrasound examination showed that her uterus measured 79×36mm. The endometrial thickness was 10.7mm, and echogenicity was homogeneous. A complex mass (74×71×67mm) with solid and cystic components was found in the left abdominal area (Figure 1A). Abdominopelvic computed tomography images (Figure 1B) showed a polycystic mass with a long diameter of 94mm in the left appendage area. A gradually expanded left ovarian artery was seen, and the mass was thought to originate from the left ovary. A hypervascular appearance of the tumor and ascites were noted.

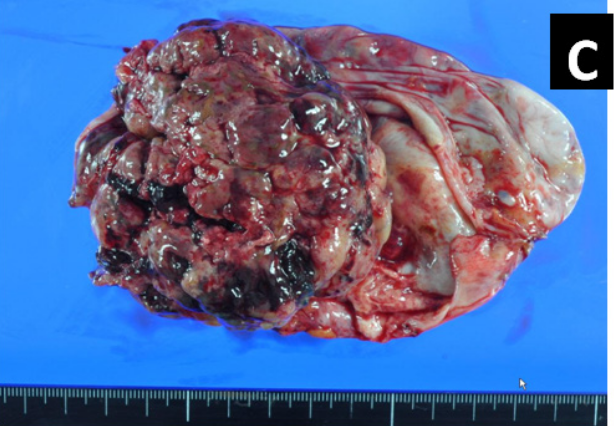

The patient underwent a laparotomy immediately after the appropriate evaluation of examinations. During surgery, the left ovarian tumor was found to be firmly adhered to the left sacral uterine ligament and pelvic wall, and the tumor showed a partial rupture, with brown liquid leaking out. Ascites showed 450ml of brown ascites. Peritoneal dissemination was not macroscopically observed. The gross appearance of the tumor was predominantly solid and lobulated with a cystic component and varying degrees of hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 1C). The patient underwent total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and partial omentectomy. Due to the emergency surgery, intraoperative histological diagnosis for ovarian tumor was not performed. The preoperative evaluation of radiological imaging revealed no evidence of lymph node swelling, therefore lymph node resection was omitted. Postoperative recovery was uneventful.

Figure 1 A) Transvaginal ultrasound examination showed a complex mass (74×71×67mm) with solid and cystic components in the left abdominal area. B) CT findings and gross appearance of the ovarian tumor. A polycystic mass in the left appendage area, indicating the tumor was derived from the left ovary. Incremental dense staining was seen from the left side to the ventral side of the cyst, and many vascular structures were found inside. C) The tumor was a solid and lobulated mass of cystic components together with varying degrees of hemorrhage and necrosis.

Subsequently, six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy were given. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin (TC therapy) was selected (paclitaxel 175mg/m2+carboplatin AUG6 on day 1; 21 d/cycle). The patient is still alive and receiving this chemotherapy at 9 months has after the operation.

Pathology

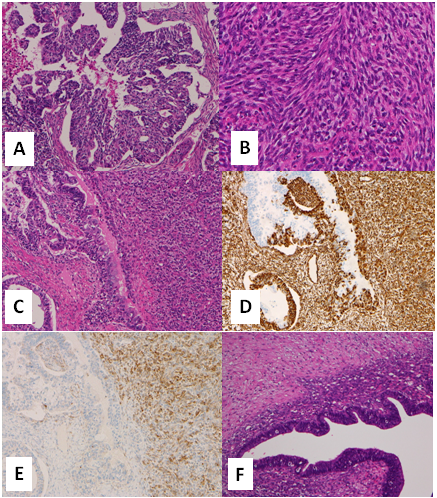

In the left ovarian tumor, epithelial and mesenchymal components were intermingled. The tubular and solid growth of the epithelial tumor cells with elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei indicated adenocarcinoma (Figure 2A). The other, mesenchymal element consisted of bundles of spindle-shaped cells with nuclear atypia (Figure 2B). Tumor necrosis and mitotic figures of both components were seen. The tumor consisted of a larger mesenchymal component (90%) and smaller epithelial component (10%) (Figure 2C). Immunohistochemistry revealed that the epithelial tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin, vimentin and estrogen receptor (ER) while the mesenchymal tumor cells were positive for vimentin and CD10 (Figure 2D & 2E). Both tumor cells were weakly and focally positive for p53, but negative for CD34, CD68, α-SMA, desmin, h-caldesmon, S-100, and myogenin. According to the morphology and immunohistochemical results, the epithelial and mesenchymal components were considered to be endometrioid carcinoma (EC) and endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), respectively. Endometriotic tissue composed of columnar epithelial cells with underlying hypercellular stromal cells was attached to the main tumor (Figure 2F). Finally, a diagnosis of ovarian carcinosarcoma (mixed EC and ESS) was made.

Figure 2 Histology of the ovarian tumor. A) Tubular and solid growth of epithelial tumor cells indicated adenocarcinoma. B) The mesenchymal element consisted of bundles of spindle-shaped cells with nuclear atypia indicating sarcoma. C) The carcinomatous (left side) and sarcomatous elements (right side) were intermingled. Both components were positive for vimentin (D) while only the sarcomatous component was positive for CD10 (E). Endometriotic tissue was attached to the tumor (F).

There was no invasion into the fallopian tubes or surrounding tissue, and the endometrium of the uterus showed no atypical cells. The patient was diagnosed with FIGO stage ⅠC2.

OCS is an extremely rare disease among gynecologic malignant tumors. Previous series have noted that women with OCS are diagnosed at an older age and have higher rates of advanced FIGO stage at presentation,4 but our case was a middle-age woman. Several studies have demonstrated that the most important prognostic factor is the clinical stage at the time of diagnosis.5 Carcinosarcoma contains both carcinomatous and sarcomatous components, and their combination varies. We experienced a case combining EC and ESS, which has not been described in many reports as summarized in Table 1.6–9 EC arises most commonly in the perimenopausal or postmenopausal age group, in the fifth and sixth decades of life, with a mean age of 56 years.10 It has been suggested that a high proportion of ovarian ECs arise from endometriotic cysts, since ipsilateral ovarian and pelvic endometriosis is seen in up to 42% of ECs.11 Ovarian ECs are associated in 15‒20% of cases with endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium.12 EC is a carcinoma showing a morphology similar to the endometrial gland. Clinically, the adenocarcinoma develops from endometriosis caused by overexpression of estrogen. In malignant conversion from endometriosis, 70% of tumors are histologically EC, but OCS and ESS are also reported.13

ESS is estimated to originate from mesenchymal tumors within ovarian endometriotic tissue or derived from the pluripotent peritoneal epithelium. In the WHO classification 4th Edition, ESS is divided into low-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma (LGESS) and high-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma (HGESS). Endometriosis is confirmed in 50% to 80% of LGESS cases. As ESS, mesodermal adenosarcoma, and OCS, these relatively rare tumors arise much more frequently in the uterus; therefore, a primary endometrial neoplasm should be excluded before assuming an ovarian origin. Primary ovarian ESSs, mesodermal (Müllerian) adenosarcomas (MAs), and carcinosarcomas are well documented, and they are presumed to arise from ovarian endometriosis.14

Endometriosis is a common condition, affecting 5‒15% of all women, and it has been estimated that 0.5–1% of cases are complicated by neoplasia. The most common malignant tumors in this setting are EC and clear cell carcinoma, each accounting for approximately 10% of ovarian carcinomas in Western countries.15 In our case, the patient had a history of endometriosis and the histological presence of endometriosis together with OCS, so it was thought that the OCS developed from the endometriosis.

The prognosis of OCS is poor, so treatment at the stage of endometriosis is recommended to prevent development of malignancy. In addition, the present case developed with acute abdomen pain caused by ovarian rupture; therefore, it was caught at a relatively early stage (Ic2). TC was chosen for postoperative therapy. TC therapy is considered one of the most effective first-line chemotherapies for OCS; further, it is thought that QOL can be maintained with this treatment, especially in elderly patients.

Because there are many cases of OCSs in the elderly, it seems that the disease prevalence may increase in the future with the aging of the Japanese population. Although there are several reports of elderly patients, there are few reports of young people and early stage, so the accumulation of similar cases is expected to determine the effect of TC therapy on patient prognosis.

This case report presents a 44-year-old woman diagnosed with OCS composed of EC and ESS. This combination is extremely rare, and its etiology and pathogenesis require further exploration. This case adds to our knowledge of the biological behavior of early-stage OCS with combination of EC and ESS.

None.

None.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

©2020 Fukushima, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.