eISSN: 2377-4304

This study aimed at establishing the epidemiological profile of sexual abuse. The study covered four years (2009–2012), with two components. One, quantitative, was based on the exploitation of all records of victims received in three crisis centers. The other, qualitative, focused on interviews of professionals involved in the care of victims. A total of 78 cases were recorded. The victims, with 14 (±7) years on average, were mostly educated in French (72%), from Dakar area (85%), students (61%), under parental supervision (55.1%), and less than 4 siblings (59%). The alleged perpetrators, whose average age is 29 (±11) years, were predominantly acquaintances (51%) and/or parents (36%) for the victims, and of unspecified profession for 69.23% of cases. The sexual abuse, incestuous in 18% of cases, was more frequently linked to rape (68%) committed at the alleged perpetrators’ (37.2%) and followed by behavioural disorder (47%), pregnancy (15%), alcoholism and/or running away (12%). According to professionals, the victims are usually minors from disadvantaged areas. The judicial concern, often the first reaction of parents, delays the post–traumatic treatment of the victim, while permanently affected by the consequences. The management should include socio–economic development; Information, education and communication, favour prevention and accessibility of functional structures with competent and motivated professionals, facilitate the treatment of residual cases.

Keywords: violence, sexual abuse, gender, girls, women, senegals

Violence is a problem that needs to be resolutely addressed. It concerns both health and human rights.1,2 Omnipresent and complex, it can be psychological, physical, verbal... and/or sexual. Sexual violence or sexual abuse is a "sexist behavior based on male dominance and power inequality between men and women". Sexual abuse includes a range of acts (imposed relationships, rape, harassment, humiliation, insults, abuse, touching, pornography, prostitution and / or forced marriage, etc.).3 Worldwide, sexual abuses are a major concern for non–governmental organizations, religious, social and political leaders. Sexual abuse is a public health problem because of its magnitude, its severity on the victims and their vulnerability linked to human behavior.3–5 They spare no strata of the population, but are exercised almost exclusively against the female; minors are the most affected.6 In some countries, one woman in four reports being a victim of sexual abuse, and up to one third of adolescents report forced sexual initiation.3 The code of silence that reigns over sexual abuses, combined with the denial of their reality, constitutes a barrier to their eradication.7 In Africa, socio–economic, cultural and traditional factors are compounded by natural disasters, demographic weight, armed conflicts and development hardship, exploitation, hunger and disabilities. In Senegal, sexual abuse has always existed, but was underestimated. It forms part of taboo subjects given the social and cultural environment; and society still tolerates male violence. Kinship, the desired and targeted value, leads to the anchoring of some ideas (solidarity, clan, sib ship) recalled by the popular saying that "dirty linen is family matter".8 Thus, the objective of this study was to establish the epidemiological profile of sexual abuse, and to propose recommendations for its prevention.

Framework of the study

Senegal, located at the extreme west of the African continent, covers 196,712 km2 and in 2014 had 14,799,859 inhabitants (75 inhabitants per km2). Dakar is the capital with 4 departments (Dakar, Guediawaye, Pikine and Rufisque) and houses the three centers that served as the framework for this study.

Type and period of study

This cross–sectional study, mixed (descriptive and analytical), covered four years (from January 2009 to December 2012), with two components: quantitative and qualitative.

Quantitative component: The exhaustive sampling was carried out on all the records of victims of sexual abuse, found in the three centers. The records were exploited based on a data sheet that contains the socio–demographic profile (age, sex, education, ethnicity, nationality, religion, place of residence), parents' situation, family type, the relationship with the alleged perpetrator, number of siblings, victim’s occupation, parental occupation, type of abuse, place of abuse, the source of information regarding the reception center. The data were entered and analyzed using the Epi Info 3.3.5 software. The description was based on the calculation of frequencies (with their confidence intervals) for the qualitative variables; and averages (with their standard deviation) for the quantitative variables.

Qualitative aspects: Four types of staff involved in the management of sexual abuse were interviewed: social workers, psychologists, child psychiatrists, and lawyers. Included were all the staff found in their structure. An interview guide was used for data collection. Direct interviews focused on the profile of victims; Risk factors, location and type of abuse, the impact on the victim and management process. The content analysis was done to synthesize the information.

A total of 78 cases were recorded: 19 at CEGID, 23 at KerXaléyi and 36 at Ginddy.

Victims

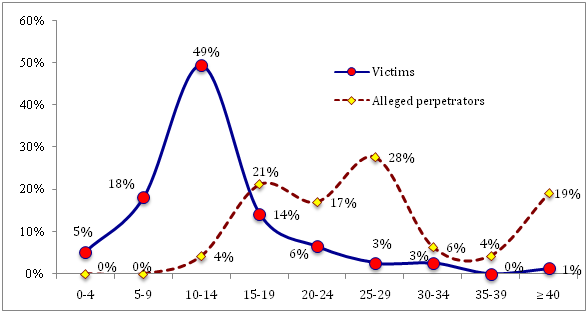

The age, varying from 3 to 52 years, had an average of 14 (± 7.04) years (Figure 1). The instruction was nil for 12%, 16% for Arabic, and 72% for French: 2% in preschool, 42% in primary, 25% in secondary school, and 3% in high school. They were mainly of Senegalese nationality (94%) and from Dakar (85%). The direct supervisor was in descending order: a guardian for 27 (34.6%), the mother for 23 (29.5%); and both parents for another 20 (25.6%). Among them, 46% were elderly; and 59% had a sibling ofless than 4. Both parents died for 3 victims, are together for 27 and are separated for 26. The occupation of the victims, unspecified for 17 cases, differentiated 48 students, 5 housewives, 2 female students, 1 shopkeeper, and 5 with no activity (Figure 2). The situation of fathers, unspecified for 21 victims, singled out 19 liberal professionals, 15 employees, 14 deceased, 6 emigrants, 2 pensioners, and 1 unemployed. Mothers included 32 housewives, 16 shopkeepers, 8 others, 6 deceased, and 16 unspecified.

Alleged perpetrators

The age ranged from 10 to 54 years, with an average of 29 (± 11.22) years (Figure 1). The alleged perpetrators were often acquaintances: 28 relatives (35.9%) and 16 friends (20.51%) for the victims (Table 1). The profession, unspecified for 54 alleged perpetrators, identified: 5 without any occupation, 3 delinquents, 3 pupils, 2 retired, 2 marabouts, 2 carpenters, 1 trader, and 1 mechanic (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Ages of alleged perpetrators and victims of sexual abuse received at the three crisis centers.

Alleged Perpetrator |

Frequencies |

|||

Relatives |

Incestuous relationship |

Stepfather |

1 |

(1%) |

Half-Brother |

1 |

(1%) |

||

Grandfather |

1 |

(1%) |

||

Uncle |

7 |

(9%) |

||

Father |

4 |

(5%) |

||

Cousin |

14 |

(18%) |

||

Other Acquaintances |

Family close relation |

7 |

(9%) |

|

Roommate |

8 |

(10%) |

||

Met on the way to school |

7 |

(9%) |

||

Marabout |

2 |

(3%) |

||

Neighbor |

15 |

(19%) |

||

Immigrants |

1 |

(1%) |

||

Unknown |

4 |

(5%) |

||

Unspecified |

6 |

(8%) |

||

Total |

78 |

(100%) |

||

Table 1 Links with the alleged perpetrator for victims in the three centers.

Sexual abuse

The location was the house of the alleged perpetrator 29 (37.2%), the victim's home 14 (17.9%) and elsewhere 35 (44%). Incestuous relations (father, uncle, stepfather, grandfather, and half-brother) involved 14 victims (17.95%). Sexual abuse was associated with rape in 68% of cases (Table 2). The consequences of sexual abuse were: a behavioral disorder for 37 victims (47.4%), pregnancy for 12 (15.4%), alcoholism or runaways for 9 (11.5%) and illness for 6 (7.7%). The source of information with regard to the centers was predominantly hospital for 13 victims (16.7%) and community-based for 13 (16.7%).

Entities |

Diversities |

Frequencies |

|

Rape and comparable practices |

Suspicion rape |

4 |

-5% |

Attempted rape |

2 |

-3% |

|

Effective rape |

41 |

-52% |

|

Repeated rape |

6 |

-8% |

|

Sub total |

53 |

-68% |

|

Others |

Cybercrime |

1 |

-1% |

Fondling |

7 |

-9% |

|

Incest |

11 |

-14% |

|

Forced marriage |

6 |

-8% |

|

Sub total |

25 |

-32% |

|

Grand total |

78 |

100% |

|

Table 2 Types of sexual abuse identified among victims received at the three crisis centers.

Expert opinion on the issue (Table 3)

The majority of victims are minors, from low-income families, entrusted to friends or guardians, and disadvantaged by the social environment (promiscuity, parental absence, instability). The abuse takes place in the victims’ place of residence or at the perpetrator’ most often close to the victims. The psychological and physical consequences permanently affect the integrity of the victims. In general, prosecution is the first concern for parents. For this, they are in need of a medical certificate and, while seeking for it, they perceive belatedly the need to consult a health facility; which can exacerbate the consequences. The post-traumatic management of the victim must be multidisciplinary and carried out in structures with trained specialists. Direct or indirect players need to be educated and to develop the ability to communicate about sexuality.

Limitations of the study

Our study was limited to three crisis centers around Dakar. Thus, recorded cases are only a fraction of the tip of the iceberg. However, other victims came from elsewhere and the duration (four years) yielded results on the epidemiological profile of sexual abuse.

Sexual abuse

The scale is difficult to assess in Senegal, where only situational studies of gender-based violence and about the management of victims are available.9 In 2002, 29.5% of cases of sexual abuse were recorded in France in 20,000 maltreated children.10 Rape, considered by the UN as "a crime", is very illustrative in our study (53%), as observed by Sy (59.30%),9 and Tursz (57%).10 In Senegal, marital rape (brutal sexual intercourse, without consent, resulting from forced marriage) is very widespread. Incest (14%) is a growing phenomenon which is justified, according to some people, by "women absenteeism at home and their fatigue while struggling to make money all along the day". In France, it accounted for 20% of assassination trials, 75% of sexual assaults against children, and 57% of rapes against minors.11

Alleged perpetrators

The alleged perpetrators generally have some authority over the victim. They are mostly young and adult, often known to the family (friend, parent, or relative): 50.9% according to Faye Diémé.12

Victims

There is a feminization of victims of sexual abuse. In 2006, of 29 children in care of Ker Xaléyi Child Psychiatry, 27 were girls aged between 2 to 13 years.13 Indeed, "male domination is so anchored in our unconscious that we no longer see it, and so given to our expectations that we have difficulty in questioning it."14 Children and adolescents of disadvantaged areas are the most affected. Age averages 14 years for 55 victims received in 2008 in Dakar at Aristide Le Dantec university hospital’s gynecological and obstetric clinic.12

Consequences of sexual abuse

The consequences depend on the type of contact, strength, frequency, age difference between the aggressor and the victim, and the environment.9,12 They are physical (trauma, STI, HIV / AIDS) and psychological (nymphomania, mother-child, rejection of the opposite sex, or even suicide), and permanently affect the integrity of the victims. The victim’s identification with the aggressor, a fundamental psychological defense system, leads some of the sexually abused to perpetuate the phenomenon in adulthood. Collateral physical violence can have serious consequences on the health of the victims.15,16 In 2012, 29% of women in rural areas of Ethiopia were victims of physical violence, and 44% of sexual violence.1 Bribes account for 43.2% of cases of gender-based violence in Niger, 20% in Burkina Faso, and 44.25% in Nigeria.17 In Senegal, in the courts of 8 regions, Niang recorded 13% fracture;18 death may occur, according to Faye.17 The psychological state of the patient is rarely evaluated (38.2%).12 In Senegal, moral and psychological violence accounted for 24% of cases in six regions.17 In Loire-Atlantique, practitioners, more interested in this field, found that psychological disorders constitute 79% of the motives for consultation.19

Sexual Abuse Predisposing Factors |

SW |

Lawyers |

Psy. |

CP |

|

Victim |

Low socio-economic class |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Middle socio-economic class |

+ |

||||

Adults + bride |

+ |

||||

Ignorance and unconsciousness |

+ |

||||

Minors |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Shyness |

+ |

||||

Sexual abuse risk factors |

Poverty / Precariousness |

+ |

+ |

||

Promiscuity |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||

Absence / parents’/guardians’lack of vigilance |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Cybercrime Development |

+ |

||||

Maltreatment |

+ |

||||

Places |

Usual route / The Way to school |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Perpetrator’ place of residence |

+ |

+ |

|||

Victim’s place of residence |

+ |

||||

Other random places |

+ |

+ |

|||

Type of abuse |

Rape and comparable practices |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Incest |

+ |

+ |

|||

Pedophilia, Corruption, Harassment |

+ |

||||

Indecent assault |

+ |

||||

Sequestration and / or fondling |

+ |

||||

Physical trauma |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||

Conse-quences |

Sexually transmitted infections |

+ |

|||

Mental and behavioral disorders |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Unwanted Pregnancy |

+ |

||||

Sense of guilt / shame |

+ |

+ |

|||

Academic failure |

+ |

||||

Management |

Pluridisciplinarity |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Giving support to potential victims |

+ |

+ |

|||

Raising awareness (especially of parents) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Child education |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||

Prosecution of perpetrators |

+ |

||||

Specialized and free support |

+ |

+ |

|||

Reference crisis Center |

+ |

||||

Table 3 Synthesis of opinions on sexual abuse by the social workers (SW), lawyers, psychologists (Psy) and child psychiatrists (CP) of the three centers.

Risk factors

The factors, multiple and diverse, of economic, social and psychological order are dominated by the solitary encounter. Indeed, for an interpersonal relationship to be possible, two individuals must share the same territory.20 Age difference is preponderant, although sexual abuse can occur between two people of the same generation. Abuse is mostly directed at adolescents.21 The average age of 14 years is consistent with the results of Mbassa,22 Mbaye,23 and the PLAN / Senegal report.24 Kempe (1979) expresses the immaturity of the victims by" still immature and dependent minors, who are unable to understand the meaning of what is offered to them and thus to give informed consent".25,26 In Cameroon, girls are more at risk (95.2%), most of them in pre puberty (41.4%) and puberty (20.2%); and aggression is more extra (74.5%) than intra family (25.5%).22 Rape is reported to be twice as common among young women (20-24 years) than among their elderly (15.3% versus 8% after 45 years) during physical violence.22 Other familial, neighborhood and / or socio professional hierarchy parameters are involved.18 Alcoholism, linked to spousal violence for some, rarely intervenes for others, and the treatment of alcoholism does not always end violence. In 2008, 58.2% of the victims received in A. Le Dantec hospital were assaulted between 7 am and 6 pm (working hours).12 Moreover, women without a diploma are five times more victims of sexual abuse outside the household than the most educated, and three times more for domestic violence.27

Management

The management has led to several encounters: 1996 in Stockholm, 2001 in Yokohama, 2008 in Dakar and Rio de Janeiro, African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child 1990. The international will is attested by the existence of The United Nations Fund for Women (UNIFEM), and the National Fund through the establishment of the National Committee for the Fight against Violence (NCFV). The responsibility of the family is engaged but the authorities must take account of the realities to achieve their eradication in accordance with the Declaration of the International Congress on Sexual Abuse held in Stockholm in 1996. In Senegal, the ignorance of crisis facilities by the population limits the support that ideally should be effective and free for a physical and mental relaxation to the cross and clinical examination of the victim.28 In Malawi, 59.5% of the victims consulted within 24 hours of the assault, 32.4% from 3 to 7 days and 8.1% more than 7 days later.29 This is contrary to Faye’s results where only 29.6% of patients were admitted within 24 hours. 12The importance of the social aspect should not upset the availability of legal orientations.9 The judicial process may be hampered by mediations30,31 and, in the absence of tangible evidence, the release, a few days after arrest, discourages denunciation. Denunciation is difficult for various reasons: aggressor being a family member, culture, victim’s or family’s fear, ignorance of the consequences and slow judicial procedures, the code of silence, etc.7,21 In Senegal, the 2001 Constitution, the Penal Code of 1965 and the Family Code of 1972 condemn all types of sexual abuses, but society prioritizes collective interest over individual. However, "family balance implies that the situation of maltreatment does not endure ... it is a question of forming an opinion on what will be most favorable for the child and his family: to inform justice or to speak of the resources of a family unit in crisis ".28 Only victims who became adults have the courage to denounce the mischief they underwent, "after several years of silence.6,7 The magnitude could be related to greater public awareness through the media, and from the professional body to more consistent mandatory reporting procedures.

Sexual abuse is a scourge with serious consequences and multiple factors, which all actors must combat by combining their efforts. Prevention through information, education and communication in urban and rural areas, as well as the introduction of the theme into school curricula, is expected to greatly reduce the number of cases. The pluri disciplinary treatment of residual cases requires the accessibility of functional structures with competent and motivated professionals to improve the health of populations in Senegal.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.