Open Access Journal of

eISSN: 2575-9086

Opinion Volume 2 Issue 6

Professor and Researcher of the Tercio Pacitti Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Correspondence: Joao Vicente Ganzarolli de Oliveira, Professor and Researcher of the Tercio Pacitti Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 550, Cidade Universit ria, Rio de Janeiro (RJ, 21941-901), Tel +5521- 3938-9600

Received: November 11, 2018 | Published: December 4, 2018

Citation: Oliveira JVG. Occitania? Yes, Occitania! A brief comment about a great and forgotten civilization. Open Access J Sci. 2018;2(6):398-399. DOI: 10.15406/oajs.2018.02.00118

Let us talk about Occitania, a very important place for all those who praise freedom of speech and all other values that served as basis for the emergence of what we call nowadays “Western Culture”. Especial emphasis is given to the fact that Occitania contributed in a fundamental way to the very survival of West Europe as a cultural entity.

Keywords: Occitania, Freedom, Western Culture, André Dupuy, Dante Alighieri

If you tell the truth, you don’t

have to remember anything.

Mark Twain

Who remembers Occitania, that small flourishing medieval kingdom which – together with Burgundy, Aragon, Flanders, Lotharingia, Palatinate and many others of the same kind – ended up by becoming a territorial part of one of the Western European countries (in this case, France), geopolitical entities brought to life during the Early Modern Period (c. 1450-c. 1850)? Excepted from this ruling is Portugal, whose current shape is practically identical to that of the Late Middle Ages: “During the Reconquista period, Christians reconquered the Iberian Peninsula from Moorish domination. Afonso Henriques and his successors, aided by military monastic orders, pushed southward to drive out the Moors. At this time, Portugal covered about half of its present area. In 1249, the Reconquista ended with the capture of the Algarve and complete expulsion of the last Moorish settlements on the southern coast, giving Portugal its present-day borders, with minor exceptions”.1 History tends to concentrate itself in the so-called “major issues”, let us say, the rise and fall of the Roman Empire – which is, by the way, the central theme of one of the most celebrated historical books of all times, namely, Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, whose six volumes were published by the first time between 1776 and 1789 – and the already mentioned Reconquista: “The Reconquista (Spanish and Portuguese for ‘Reconquest’) is a name used in English to describe the period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula of about 780 years between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada to the expanding Christian kingdoms in 1491. The completed conquest of Granada was the context of the Spanish voyages of discovery and conquest (Columbus got royal support in Granada in 1492, months after its conquest), and the Americas – the New World – ushered in the era of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires”.2

Carcassone, one of the most famous and beautiful

cities of Occitania and of France itself

(Photo taken by the Author)

In Roman Times, most of Occitania was called Aquitania, a name derived from the earliest attested inhabitants of the land, the Aquitani, a people more akin to the Iberians than to the Celts. There is reason to believe that the Aquitani spoke Proto-Basque, “a reconstructed predecessor of the Basque language, before the Roman conquests in the Western Pyrenees”.3 The term Occitania can be interpreted in different ways: a) since 2018, Occitanie designates an administrative region in Southern France that succeeded the regions of Midi-Pyrénées and Languedoc-Roussillon. In terms of area, it is a small part of “historical Occitania”, so to say.4 b) Historically speaking, Occitania is a southern Europe’s region, which encompasses southern France, along with fractions of Catalonia, Monaco and even of Italy (Occitan Valleys and Guardia Piemontese); its common denominator is the language, the Occitan: main language spoken in the middle Ages, second language spoken nowadays.5 Stemmed from Medieval Latin, the very name Occitania has an alluring background, which has everything to do with this specifically human faculty which is language: occ comes from oc and means “yes” in Occitan, as opposed to oïl – “yes” in the medieval dialects spoken in the northern part of what is now France –, which turned out to become oui in modern French. “Languedoc”, geographically speaking a territory contained in Occitania, means, literally, “the language of oc”; and denotes, in a wider context, a place where people say oc when they mean “yes”, affirmative particle used to “give a positive response to a question”, “to accept an offer or request, or to give permission”, “to tell someone that what they have said is correct”, “to show that you are ready or willing to speak to the person who wants to speak to you, for example, when you are answering a telephone or doorbell”, “to indicate that you agree with, accept, or understand what the previous speaker has said”, “to encourage someone to continue speaking” and so on.6

On the same topic, Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), prince among poets of all times and places, wrote on the eve of European Renaissance: nam alii oc, alii sì, alii vero dicunt oil (“some say oc, others say sì, others say oïl”).7 According to him, the langue d’oïl, ancestor of Modern French, prevails when it comes to prose, notably narrative and didactic; the langue d’oc (= Occitan, as already seen before), in turn, deserves first place in terms of sweetness and elaboration, let alone the merit of having been the raw-material used by the first West European poets who preferred to write in vernacular instead of in Latin, among them, Dante Alighieri himself and his friend Cino da Pistoia (1270-1336).8

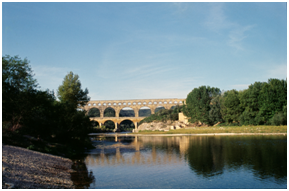

Ancient times in Occitania: Pont de Gard, one of the

best preserved of all Roman aqueducts

(Photo taken by the Author)

Born in 1928 at Lavit-de-Lomagne, the Occitan historian André Dupuy – with whom I had the pleasure to talk personally in the year 2000 – considers Occitania “a country with bad luck”, in his Encyclopédie Occitaine.9 Indeed, political fragmentation has been the rule for this beautiful land, cradle of queens like Eleanor of Aquitania (1122[?]-1204), patron of literature and Commander-in-Chief of a Crusade,10 painters like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), and polymaths like Blaise Pascal (1626-1662), who was mathematician, physicist, inventor, writer, philosopher and theologian. It is also important to stress that Occitania, in the Early Middle Ages (more precisely, between 721 and 972), played a major part in the defence of Western Europe against the Muslim aggressor, who had already spread havoc in the Middle East, North Africa and many parts of Europe, notably the Iberian Peninsula.11 In other words, thanks to Occitania, we, Western people, were saved from slavery and annihilation Occitania? Yes, Occitania!

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Oliveira. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.