Open Access Journal of

eISSN: 2575-9086

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 3

1Entrepreneurship Development Centre, Federal University Otuoke, Nigeria

2Department of Office and Information Management, Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Nigeria

Correspondence: Raimi Aziba-anyam Gift, Entrepreneurship Development Centre, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Received: July 19, 2020 | Published: August 19, 2020

Citation: Gift RAA, Obindah F. Examining the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa state private hospitals. Open Access J Sci. 2020;4(3):94-108. DOI: 10.15406/oajs.2020.04.00157

Pushing through the 21st century, the vast amount of accumulated theoretical knowledge and practical experience related to human resources as well as the ever growing need to seek new ways to survive and compete in the global economy. The new complex industry and global competitive conditions also create an increased interest in understanding the multidimensional nature of motivation on the overall organizational productivity. Hence, private hospitals in Bayelsa State are faced with challenges which impedes on successful service delivery. While, motivation is increasingly seen as underlying an organizational productivity. The overall workplace behaviour has been recognised as an important element in organisational performance. This perspective views the influence of motivation as crucial in sustaining an organizational productivity. The population of the study was 204 comprising office managers and other staff in ten different hospitals in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State. A sample size of 135 was gotten using taro Yamane formula. This study adopted a descriptive survey design. Methods used to analyse the data were mean, standard deviation and simple regression. The instrument used for this study was a questionnaire titled Eustress and Organizational Productivity in Bayelsa State Private Hospitals. Reliability of the instrument was tested using cronbach’s alpha statistical tool and it yielded a coefficient level of 0.768. All the research questions were answered using standard deviation and mean. While all the hypothesis were tested with 0.05 level of significance. Results shows that 12.5 percent of the variation in organizational productivity was accounted for by motivation. Meaning that improvement in motivation will result to corresponding improvement in organizational productivity. It also reveals that the F-calculated (18.958) is greater than the F-critical (3.91) at 0.05 level of significances which means that there is a significant linear relationship between motivation and organizational productivity. Therefore, there is a significant influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals. The result indicates that the higher the level of motivation, the better the organizational productivity among office managers’ in Bayelsa State private hospitals. Based on the findings, the study concludes that organization can improve productivity by motivating and promoting their office managers. The researcher put forward some recommendations which includes; private hospitals should have a well-articulated strategies in motivating and promoting their employees on the aspect of motivation, office managers should be encouraged, but should be applied moderately and in the long-run, a continuous improvement mechanism by various stakeholders in the private hospital is deemed necessary to maintain delivery standards.

Keywords: motivation, private hospitals, organizational productivity, service delivery, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

OND/NCE/CRN, ordinary national diploma/national certificate examination/certified registered nurse; SSCE, senior secondary school certificate examination

Communication among the organization and team members depends on what inspires them for the work, the benefits it brings and the attendant fulfilment of the employees who derive it. The fundamental motivation concept is the driving force in individuals who attempt to reach a goal to meet a need or an expectation.1,2 Hence, the survival and growth of private hospitals in a dynamic milieu of Bayelsa State and the conditions of increasing competition are therefore dictated by factors such as strategic thinking and happenings, notably through innovativeness and improved efficiency. Defining these snags by means of effective management entails the collaboration and commitment of all employees in the establishment’s, hence a great remarkable attribute of employee drive in the process of implementation. Many private hospitals have been challenged to increase their compensation incentives and motivation schemes in relations to increasing the effect of other motivation factors, thereby fine-tuning the organization’s financial situation. Upgrading to a reinforcement motivation system of improvements is a complex procedure that necessitates a wide-ranging and in-depth research and evaluation of the solutions that are currently applied. In essence, for office managers to perform optimally, there must be a propelling force. Motivation is an inner desire to satisfy an unsatisfied need. The willingness to achieve organizational objectives or go beyond and above the call of duty.3 It has been observed that the presence of certain positive stressors or eustress, coerces workers to work with a competitive spirit. They appreciate these positive stressorswhich allows them to work at their full capacity. Positive stress creates a higher employee’s performance. Nevertheless, the non-appearance of positive stress does not, of course, mean that the workers have adverse stress. It just shows that the employees are not under positive stress.

According to Griffin4 productivity in the general sense is a measure of economic efficiency that summaries the value of inputs used to create them. In relation to our study office manager productivity is referred to the number of productivities accomplished by an organization unit or department with the output level achieved by a single individual. Efficiency refers to estimated productivity effects; precisely, productivity with minimal form of waste. This has to do with the abilities of workers to work efficiently with minimum waste in relations to energy, cost and time. Efficiency is likewise more or less a contrast between using an input in an evidently defined process and an output that is generated. Efficiency denotes the ability to generate the maximum performance from the given input provided with a least waste of time, energy, effort, raw materials and money. It can be quantitatively measured by designing and achieving a share of the company's input-output ratios such as funds, electricity, equipment, labour, etc. Surbhi.5 According to Bono & Judge6 a needy or a want motivates a behaviour. However, needs and motives are complex; people don’t always know what their needs are or why they do things they do. Understanding needs will help you understand behaviour7 and understanding that individuals are motivated by selfishness is important in the understanding of motivation. Motivation is an important part of workers productivity and performance. It denotes the power of the individual to influence his or her path, intensity, and the tenacity of voluntary behaviour.8 In the words of Rue & Byars,9 motivation remains concerned by means of what activates human behaviour, leading them to a specific goal and how it can be sustained. On the other hand, Jones & George,10 say that motivation is an emotional force that determines the personality traits of an individual’s behaviour in the organization, the level of individual effort, and the level of a personal persistence.

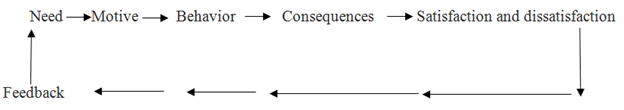

Nevertheless, whether the motivation is well-thought-out by the employee vision of work and productivity perspective or from the path and persistence of actions, it is certainly in the context of a goal-directed behaviour. Hence, motivating other individuals require effort to move in the chosen direction to attain results. For example,11 states that individuals are motivated when they assume that a plan may be able to provide a meaningful goal attainment and a cherished reward (which satisfies their needs). In addition to the purpose of goal accomplishment, worker performance and action route viewpoints. Luthans & Doh12 submit that motivation is therefore a psychological procedure through which unsatisfied desires or needs towards a drive that are designed at goals or motivations, and an individual with an unfulfilled need will adopt behaviors that reflect the desire to meet needs. Hence, as a psychological procedure where employees set goals to attain their diverse needs, organizations must offer different approaches to ensure that employee’s personal goals are accomplished in a way that can help achieve organizational goals. Motivation is a process, that is why White13 says through motivation procedure, employees return from need to motive to conduct through consequence to satisfaction and dissatisfaction (Figure 1). According to Robert14 motivation process is a feedback process. Below is the diagrammatic representation of motivation process.

Figure 1 A diagram showing motivation process.

Source Adapted from Robert (2008) Organizational Behaviour: Core Concepts (6th edn)

Generally, a motivated employee will try harder than an unmotivated one to do a good job. According to Mullins15 productivity and quality service are improved when positive incentive philosophy and practice are made, since motivation aids individuals towards: attaining goals, gaining an optimistic viewpoint, creating the influence to change, building self-image and capability, and to advance development besides helping others. Jennifer & George16 describe motivation as a psychological power that directs the course of a person’s behaviour in an organization, an individual’s role and an individual’s level of decision in adversity. Additionally, she added that although with the right strategies and administrative structures in position, an organization can still be profitable if its employees are motivated enough to do their best. George & Jones17 refer to the work motivation as a driving forces that promotes the directions and behavioural patterns of the workers in an organization by developing their levels of commitment and enthusiasm to achieve their objectives. Berelson & Staines18 believe that motivation is an internal component that directly promotes actions including direct and channel behavior in the direction of a goal. Guay et al.,19 argued that motivation is linked to “the motives underlying factors”. Additionally,20 describe motivation simply as “those rudiments that pushes a person to act or not to act”. This paper analyzed the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals. Findings from this study will shed more light on the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals and make recommendations to the appropriate authorities. Hence this study was initiated with the objective of examining the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa state private hospitals? Its aim is to develop a novel, efficient system that supports the attainment of strategic objectives that guarantee their competitiveness through labour cost justification, attracting topnotch specialists and shaping suitable attitudes of executives and employees to the allotted tasks and organizational goals.

Research design

According to Abdulraheem et al.,21 Research Design refers to how a piece of research is planned and carried out. The study adopted the Descriptive Survey Research Design to meet its purpose. According to Wimmer & Dominick,22 surveys describe current conditions or attitudes as well as explain the reason for certain existing situations. The survey method has the advantage of effectiveness in obtaining information about personal perceptions, beliefs, feelings, motivations, anticipations and future plans as well as past behaviours. Raimi et al.,22 Funmilayo et al.,14 opines that survey method interprets, synthesizes and integrates useful data for sound conclusions. The study is reliable since it scrutinized the association that occurred between motivation and organizational productivity in Bayelsa state private hospital. The study design provided a numerical account of outlines or trends, attitudes, or views of the administrative staff’s.24 This allowable generalization from the model around the population according to inferences made about the organizational productivity in private hospital in Bayelsa state. The design of the study was chosen since it is economically viable and easy to collect data.24 The survey method was cross-sectional using structured questionnaire as the tool for collection of primary data, and therefore the numerical nature of the study.

Research population

Population refers to the entire subjects that the researcher will get information from. My population is a finite population which are, the number of senior administrative staff working in private hospitals in Bayelsa state. www.explorable.com. Research population is usually a huge collection of people or objects that is the subject of a scientific examination. It is for the advantage of the population that researches are completed. Amadi25 says population of study signifies the entire class of people, object, events or elements to which generalizations are to be inferred. A research population islikewise identifiedas a well-defined assembly of individuals that have similar characteristics. Thus, the population of this study comprised of two hundred and four (204) consisting of directors, administrative staff, record staff and any other cadre in ten (10) different private hospitals in Yenagoa, Bayelsa state, namely.

The study area

Location: Yenagoa turn out to be a state Capital when Bayelsa State was founded in 1996, Yenagoa is physically situated between latitude 4o 47‟15‟ and 5o 11‟ 55” Northings and Longitude. 6o 07‟ 35” and 6o 24‟ 00” Eastings (Figure 2). The LGA covers an area of 706 km² with a population of 353,344 comprising of 187,791 male and 165,553 females with a yearly exponential growth rate of 2.9 according to the 2006 National Censu.26 The Yenagoa Local Government Area (LGA) borders Mbiama communities of Rivers State to the North and East, Kolokuma/Opokuma LGA to the North-West, Ogbia LGA to the South East and Southern Ijaw to the South-West.14,27,28 The Local Government Area of Yenagoa is situated on the banks of the Ekole Stream, one of the main banks of the Niger Delta river,29,30 with a single political constituency namely: Epie-Atisa.27 There are 21 communities in the study area namely; Igbogene, Yenegwe, Akenfa, Edepie, Agudama, Akenpai, Etegwe, Okutukutu, Opolo, Biogbolo, Yenizue-Gene, Kpansia, Yenizue-Epie, Okaka, Azikoro, Ekeki, Amarata, Onopa, Ovom, Swali, Yenagoa.14,31 The Local Government Area of Yenagoa is the traditional home of the people of Ijaw, the fourth largest city in Nigeria after the Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo. English is the official language, but Epie/Atissa dialectis the main language spoken in Yenagoa. Other Ijaw dialects includes Tamu, Mein, Jobu, Oyariri, and Tarakiri.

There are other pocketsof tribes like Urhobo and Isokoin some places in Yenagoa. The other prevalent languages in the LGA are Epie, Atisa, Nembe and Ogbia. Christianity and traditional religion are the two main religion in the State.The culture of the people is reflected in their various dressing pattern, festivals, food systems, artistries, folklore and dance. This is unique for people of all races. The main skills are canoe building, fishing net and fish traps making, pottery, basket and mat making (Figure 2).14,31

Climate: Yenagoa region lies firmly in the equatorial climatic belt, which is dominated by extreme heat, humidity and heavy rainfall. The predominant winds are North-East trade winds. There is great consistency of temperatures all year round. The average monthly temperature is between 260c to 280c.The land and sea temperatures are moderated by frequent breezes as a result of the Atlantic Ocean influence. The annual rainfall is heavy, between 3,000mm to 3,500mm. The rainfall system is quite different and between December to February is slightly dry season. The rain is accompanied by lightening thunder and heavy showers. The region’s soil erosion is high between 80% - 85% per year. This is as a result of availability of water supply in the region and global warming due to the high temperatures.2

Topography and vegetation: The zone is crisis-crossed by many rivers and creeks (especially the Nun River, Ekole and the Epie creeks). Therefore, there are flood plains and back swamps that support a variety of plants and animals. Already water bodies are to lend a unique and insistent characteristic of the site. Depositional activities across the Ekole creek has shaped an interesting physical feature known as ‘Ox-bow Lake’ near Swali in the Southern part of the site. The fresh water swamp forest type offlora comprises of tall and thick shady trees, climbers, shrubs and grasses, as well as other economic tress like Raffia palm and Oil palm trees, Wild/African Mango, Crocuces, Ogbono, etc. It also houses one of the prime timber concentrations, oil-palm and numerous forest products as well as non-fossil products such as the finest qualities and ceramic clay varieties, gravel and sand. In addition to these, the area is richly supplied with streams and ponds, which are home to reptiles, fishes and hydrophytes such as the water lettuce (Pistiastraliotes), water Hyacinth, (Eichhorniacrassipes), waterlily, (Nymphea lotus) and so on.It has a dense forest vegetation with flourishing type, due to extreme temperature and heavy rainfall which supports constant vegetation growth throughout annually. Floating flora like water hyacinths along the creeks and rivers are also present.14,32

Socio-economic activities: The socio-economic activities of the people of Yenagoa are mainly fishing, farming, palm oil milling, lumbering, weaving and trading. Almost half of the population are engaged in agricultural activities. Due to its well-endowed crude oil and gas resources, the area is host to three Gas flare sites and flow stations located at Oporoma, Ogboinbiri and Imiringi communities. With the area naturally endowed with abundance of natural resources especially deposits of oil and gas, as a result, petroleum production is one of the sustaining economic activities in the area., extensive forests, excellent fisheries, thus another occupation which is in vogue in the area and good agricultural land, which is another mainstay their economy, it is certain that these may continue to be the attraction and pull factors for immigrants to the region.30,32

Population and settlement: 2006 population census put Bayelsa State toapproximately1,704,515 people. Yenagoa Local Government Area constitutes a total population of 352,285 which 182,240 are male and 170,045 females in 2006 (National Population Commission, 2010) while the projected figure for 2015 is 459,693 (Health Development Plan: Bayelsa State Ministry of Health, 2010).Bayelsa State people were very migratory in nature. This in itself, due to a number of related factors include environmental, economic and historical factors and developments. Traditionally, it is likely to know these issues and developments: intra-and-inter-communal hostilities, human activities, slave trade, government policies, the world war and the Nigerian civil war.29,30,32 The population in this study, 352,285 residents of the Yenagoa Local Government area encompassing 182,240 males and 170,045 females (National Population Commission, 2006) and in 2017, the projected population with annual exponential growth rate of 2.9% as population growth rate as at the 2006 according to the National Census.26 This gives a total population of 482,462 people.

Sample size

The sample size of 135 was gotten using Taro Yamane formula (1967) as shown below:

n = Sample size to be determined, e = Level of significance and N = Population size.

Instrumentation and measurement

Instrumentation is the method used to administer instrument to the respondents. The instrumentation for this study was questionnaire designed after an extensive literature review. The researcher took cognisance of the research question as well as the hypotheses in a manner that enables the researcher gather as much information as possible from the respondents. Structurally, the questionnaire was divided into three sections A, B and C. The section A, was the introductory aspect which consist of a cover letter introducing the researcher with the school letter-headed paper signed by the researcher assuring them of information confidentiality. The section B, was demographic data will consist of personal information or attributes of the respondent such as sex, age, etc, and the section C, was the core questions that questions that strictly relate to the purpose of the study, by putting your conceptual framework into consideration.

Validity of instrument

To determine the research validity of the questionnaire (instrument), the original copy of the research questionnaire (instrument) was validated by the research supervisor for review whether they are suitable for the purpose of the study, research questions, hypotheses and the language that is used to develop the item. The supervisor make correction where necessary and modify the instrument before it was administered to the selected respondents.

Reliability of instrument

To determine the instrument reliability, 25 copies of the instruments were tested on 25 employees which were not included in the main study but were part of the population. The data obtained were analysed using Cronbach’s Alpha statistical tool. Results yielded reliability coefficients of .768. These reliability coefficients were considered high enough to justify the reliability of these instruments. Summary results of the reliability analysis are presented below:

Administration of instrument

As earlier stated a questionnaire was administered by the researcher to the respondents directly or was given to the administrative heads or managers of the various hospitals which in turn will hand over the instrument (questionnaire) to the office managers working in private hospitals such as directors, administrative staff, etc. for coordination purpose. The scaling items was 5-pointlikert scale, which include; strongly agree, agree, undecided, strongly disagree and disagree. This scaling method was used to measure the relationship between eustress and organizational productivity.

Data analysis technique

Both descriptive and inferential statistics were analysed using Information obtained. Data were analysed using frequency and percentages, mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis, simple and multiple regression. All hypotheses were tested at the 0.05 level of significance (Tables 1–3).

|

S/N |

Names of hospitals |

Address of hospitals |

Director |

Managers |

Admin staff |

Record staff |

|

1. |

Gloryland Hospital |

Opposite New Commissioner Quarters,Okutukutu, Yenegoa |

1 |

1 |

25 |

9 |

|

2. |

Family Care Hospital |

No. 108 AIT/Elebele Road, Opolo, Yenegoa |

1 |

1 |

16 |

6 |

|

3. |

Asueifai Hospital |

No. 14Asueifai Street Off Baybridge Road, Yenegoa |

1 |

1 |

33 |

6 |

|

4. |

Tobis Clinic and Consultants |

Akenfa-epieMelfordOkilo Road, yenegoa. |

1 |

1 |

12 |

4 |

|

5. |

Grand Care Hospital |

No. 30 Tinancious Street, Edepie, yenegoa |

1 |

- |

8 |

6 |

|

6. |

Everly Medical Centre |

Erepa, MelfordOkilo Road, Yenagoa |

1 |

1 |

10 |

5 |

|

7. |

Chansmy Hospital and Maternity |

No 7 INEC Road, Yenegoa |

1 |

- |

5 |

3 |

|

8. |

Crest Consultants Hospital |

Jasmine Road,Kpansia Yenagoa, |

1 |

1 |

16 |

7 |

|

9. |

Good Shepherd Specialist Hospital |

Akoi by PDP Road, Yenagoa. |

1 |

1 |

7 |

3 |

|

10 |

Rufus Hospital Ltd |

Otiotio Road, Yenagoa. |

1 |

- |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Total |

|

10 |

7 |

135 |

52 |

|

|

Grand Total |

|

|

|

|

204 |

Table 1 Population distribution

Source: Hospital management (2019)

|

Cronbach's Alpha |

Cronbach's Alpha Based on standardized items |

No. of items |

|

0.768 |

0.768 |

45 |

Table 2 Summary result of the Cronbach Alpha reliability result for the instrument

|

No. of Respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Male |

51 |

37.8 |

|

Female |

84 |

62.2 |

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 3 Distribution of the respondents by gender

Source: Field survey, 2019

Demographic analysis

Result shows that 37.8% of the respondents were male and 62.2% were female. Result shows that the majority of the respondents were female (62.2%) (Table 4). Result shows that 25.9% of the respondents were selected from Gloryland Centre, 7.4% were from Family Care Hospital, 26.8% were from Asuiefai Hospital while 7.4%, 3.0%, 10.4%, 3.7%, 3.0%, 9.6% and 3.0% of the respondents were from Tobis Clinic and Consultants, Grand Care Hospital, Everly Medical Centre, Good Shepherd Specialist Hospital, Rufus Hospital Ltd, Crest Consultant Hospital and Fertility Centre and Chansmy Hospital and Maternity. Results indicate that larger percentage of the respondents (26.7%) were from Asuiefai Hospital.

|

No. of Respondents |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

Valid |

Gloryland Medical Centre |

35 |

25.9 |

|

Family Care Hospital |

10 |

7.4 |

|

|

Asuiefai Hospital |

36 |

26.7 |

|

|

Tobis Clinic and Consultants |

10 |

7.4 |

|

|

Grand Care Hospital |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Everly Medical Centre |

14 |

10.4 |

|

|

Good Shepherd Specialist Hospital |

5 |

3.7 |

|

|

Rufus Hospital Ltd |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Crest Consultant Hospital and Fertility Centre |

13 |

9.6 |

|

|

Chansmy Hospital and Maternity |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 4 Distribution of the respondents by the name of the hospital

Source: Field survey, 2019

Result in Table 5 reveals that 1.5% of the respondents were in Human Resources Management, 37.0% were in Administrative, 19.3% were in Finance, 19.3% were in Records, 0.7% was in Marketing while 22.2% of the respondents belong to other department. Result indicates that the majority of the respondents were Administrative staff (37.0%) (Table 6).

|

Department |

No. of respondents |

Percentages (%) |

|

|

Valid |

Human resources management |

2 |

1.5 |

|

Administrative |

50 |

37 |

|

|

Finance |

26 |

19.3 |

|

|

Records |

26 |

19.3 |

|

|

Marketing |

1 |

0.7 |

|

|

Others |

30 |

22.2 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

|

Table 5 Distribution of the respondents by department

Source Field survey, 2019

|

Age (years) |

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

18 – 29 |

28 |

20.7 |

|

|

30 – 39 |

88 |

65.2 |

|

|

40 – 49 |

14 |

10.4 |

|

|

50 – 59 |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Above 60 |

1 |

0.7 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

|

Table 6 Distribution of the respondents by department age (years)

Source: Field survey, 2019

Results presented in Table 6 reveals that 20.7% of the respondents were between 18-29 years, 65.2% were between 30-39 years, 10.4% were between 40-49 years, 3.0% of the respondents were between 50-59 years while 0.7% of the respondents were above 60 years. Table 7 presents the distribution of the respondents by their highest level of education. Results shows that 3.0% of the respondents had SSCE or equivalent, 5.2% had OND/NCE/CRN while 14.8%, 68.1%. 4.4% and 4.4% of the respondents had Polytechnic, University, Postgraduate Degrees and other qualifications respectively. Result indicates that the majority of the respondents had university degrees (Table 8). Result reveals that 54.8% of the respondents were single, never married, 1.5% were single, widow and 43.7% were married or remarried. Result shows that the majority of the respondents were single, never married (Table 9).

|

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

SSCE or Equivalent |

4 |

3 |

|

|

OND/NCE/CRN |

7 |

5.2 |

|

|

Polytechnic |

20 |

14.8 |

|

|

University |

92 |

68.1 |

|

|

Postgraduate Degrees |

6 |

4.4 |

|

|

Others Specify |

6 |

4.4 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 7 Distribution of the respondents by highest level of education

|

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

Valid |

Single, Never Married |

74 |

54.8 |

|

Single, Widow |

2 |

1.5 |

|

|

Married or remarried |

59 |

43.7 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 8 Distribution of the respondents by marital status

Source: Field survey, 2019

Result in Table 9 shows that 11.1% of the respondents were Yoruba, 34.8% were Ijaw, 3.0% were Hausa, 24.4% were Igbo and 26.7% of the respondents belong to other religion (Table 10).

|

No. of Respondents |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

Valid |

Yoruba |

15 |

11.1 |

|

Ijaw |

47 |

34.8 |

|

|

Hausa |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Igbo |

33 |

24.4 |

|

|

Others |

36 |

26.7 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 9 Distribution of the respondents by ethnicity

Source Field survey, 2019

|

|

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Valid |

1 – 5yrs |

79 |

58.5 |

|

6 – 10yrs |

37 |

27.4 |

|

|

11 – 15yrs |

15 |

11.1 |

|

|

16 -20yrs |

2 |

1.5 |

|

|

> 20yrs |

2 |

1.5 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100.0 |

|

Table 10 Distribution of the respondents by experience

Source: Field survey, 2019

Result indicates that 58.5% of the respondents had 1-5 years of experience, 27.4%, 11.1%, 1.5% and 1.5% of the respondents had 11-15 years, 16-20 years and above 20 years’ experience (Table 11).

|

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

Less than 50,000 |

95 |

70.4 |

|

|

50,000 – 100, 000 |

29 |

21.5 |

|

|

101,000 – 150, 000 |

9 |

6.7 |

|

|

Above 150,000 |

2 |

1.5 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 11 Distribution of the respondents by monthly income

Source: Field survey, 2019

Result in Table 11 shows that 70.4% of the respondents had Less than 50,000, 21.5% had 50,000–100, 000, 6.7% had 101,000–150, 000 and 1.5% of the respondents had Above 150,000. Result shows that the majority of the respondents had less than 50,000 (Table 12).

|

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

||

|

Valid |

Junior Staff |

66 |

48.9 |

|

Senior Staff |

69 |

51.1 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100 |

Table 12 Distribution of the respondents by class category

Source: Field survey, 2019

Result reveals that 48.9% of the respondents were junior staff while 51.1% were senior staff (51.1%). Result shows that the majority of the respondents were senior staff (Table 13). Result reveals that 1.5% of the respondents were Director, 3.7% were Manager/Assistant Manager, 14.8% were Accountant, 33.3% were Administrative Staff, 22.2% were Health Record Officer, 3.7% were Lab Attendant and 20.7% were others. Result shows that the majority of the respondents were Administrative Staff (33.3%).

|

|

No. of respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Valid |

Director |

2 |

1.5 |

|

Manager/Assistant Manager |

5 |

3.7 |

|

|

Accountant |

20 |

14.8 |

|

|

Administrative Staff |

45 |

33.3 |

|

|

Health Record Officer |

30 |

22.2 |

|

|

Lab Attendant |

5 |

3.7 |

|

|

Other |

28 |

20.7 |

|

|

Total |

135 |

100.0 |

|

Table 13 Distribution of the respondents by designation

Source: Field survey, 2019

Bivariate analysis

Hypothesis 1

HO1 - There is no significant influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals. Table 14 shows r-square of 0.125 which means that 12.5 percent of the variation in organizational productivity was accounted for by motivation. This result also signifies that if there is any improvement in organizational productivity it would be mostly because of an improvement in motivation. This invariably means that an improvement in motivation will result to corresponding improvement in organizational productivity. The result of the Analysis of Variance for the regression is shown in Table 15.

|

Model |

R |

R square |

Adjusted R square |

Std. error of the estimate |

|

1 |

0.353 |

0.125 |

0.118 |

5.92725 |

Table 14 Model summary showing the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals

Source: Researchers Computation with SPSS 20

|

Source of variation |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F-calc. |

F-calc. |

P-value |

|

|

|

Regression |

666.038 |

1 |

666.038 |

18.958 |

3.91 |

0.0000 |

|

Residual |

4672.599 |

133 |

35.132 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

5338.637 |

134 |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 15 ANOVA Result summary showing the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals

*significant at p<0.05. Source: Researchers Computation with SPSS 20.

From Table 15, the F-critical of 18.958 was obtained with p-value of 0.0000 while the F-critical of 3.91 at the 0.05 level of significance. The result reveals that the F-calculated (18.958) is greater than the F-critical (3.91) at the 0.05 level of significances which means that there is a significant linear relationship between motivation and organizational productivity. Table 16 presents the regression coefficient for the model parameters. The regression coefficient of 0.692 was obtained, which means that there is a positive relationship between motivation and organizational productivity. The standardized regression coefficient of 0.353 was obtained which indicates that for every unit improvement in motivation, organizational productivity will increase by 0.353. Result also reveals that motivation (β=0.692, t-calc. =4.354, t-crit. =1.98, p=0.0000, p<0.05) has a significant positive influence on organizational productivity. Result also shows that t-calculated (4.354) is greater than the t-critical (1.98) at the 0.05 level of significance. Hence, the null hypothesis stated above is rejected. Therefore, there is a significant influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals. The result indicates that the higher the level of motivation, the better the organizational productivity among office managers’ in Bayelsa State private hospitals (Appendix).

|

Model |

Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t-calc. |

P-value |

||

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

||||

|

(Constant) |

70.698 |

2.883 |

24.525 |

0 |

||

|

Motivation |

0.692 |

0.159 |

0.353 |

4.354 |

0.000* |

|

Table 16 Parameter estimates of the regression model for the influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals

*significant at 5%(p<0.05), t-critical = 1.98. Source Researchers Computation with SPSS 20

Section A: Demographics of the respondents

Basic demographic data

[ ] Gloryland Medical Centre [ ] Family Care Hospital [ ] Asuiefai Hospital

[ ] Tobis Clinic & Consultants Hospital [ ] Grand Care Hospital [ ] Every Medical Centre

[ ] Good Sherpherd Specialist Hospital [ ] Rufus Hospital Ltd [ ] Crest Clinic and Consultant Hospital[ ] Chansmy Hospital and Maternity

[ ] Human Resources Management [ ] Administrative [ ] Finance

[ ] Records [ ] Marketing [ ] Others

[ ] 18 – 29 [ ] 30 – 39 [ ] 40 – 49 [ ] 50 – 59 [ ] Above 60

[ ] SSCE or Equivalent [ ] OND/NCE/CRN[ ] Polytechnic [ ] University

[ ] Postgraduate Degrees [ ] Others Specify

[ ] Single, Never Married [ ] Single, Divorced[ ] Single, Widow (partner/spouse deceased)

[ ] Married or remarried[ ] Separated [ ] Other

[ ] Yoruba[ ] Ijaw [ ] Hausa[ ] Igbo [ ] Other

[ ] 1 – 5yrs [ ] 6 – 10yrs [ ] 11 – 15yrs [ ] 16 -20yrs[ ] > 20yrs

[ ] Less than 50,000 [ ] 50,000 – 100, 000[ ] 101,000 – 150, 000 [ ] Above 150,000

[ ] Junior Staff[ ] Senior Staff

[ ]Director [ ]Manager/Assistant Manager [ ] Accountant [ ] Administrative Staff

[ ] Health Record Officer[ ] Lab Attendant [ ] Other

[ ] Tenured[ ] Confirmed [ ] Temporary[ ] Regularised[ ] No tenure system for my department

[ ] Other (Please Specify)

Section B: Eustress questionnaire

Instruction: Indicate the option that best suits your opinion of each of the following by ticking. SA, strongly agree; A, agree; UN, undecided; D, disagree; SD, strongly disagree

|

S/N |

Items |

SA |

A |

UN |

D |

SD |

|

|

Job rotation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Job rotation encourages skill & performance improvement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

It does not lead to stress while shifting to a new job |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

It helps in career planning & progression of employee |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

It lead to avoidance of frauds |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

It is not a frequent interruption in employee work life and has no effect on personal life |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

It is a process of managing talent and beneficial to the organization as well |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

It reduces monotony in the discharge of duties |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Job enlargement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Office managers are clear about their task in the organization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

Office managers enjoy work-life balance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

The organization has a well-defined task structure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

Office manager’s job allocation is based on skill and knowledge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

Office managers are offered opportunities for career advancement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

Employees understand processes and procedures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Promotion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

My organization provides opportunities for career advancement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

Promotion motivates me to work harder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

Promotion is based on performance in my organization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

Promotion is based on knowledge and skills in my organization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

Promotion is based on knowing a top management personnel in my organization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motivation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Motivation reduces rate of employee absenteeism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

Motivation reduces work stress |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

Motivation has increased employee performance work level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

I receive recognition or praise for doing great work |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

I have all resources I need to do my best everyday |

|

|

|

|

|

A review of the samples in question

Before deciding on the statistical results, it is necessary to examine the questions to determine from what precise population the results were generated. In relations to gender, significant difference was observed in the gender participants distribution in their classification. The results of female respondents was62.2% larger than the figure of male respondents. The study results revealed great discrepancies. 62.2% of the women compared to 37.8% of the male, which means that two-thirds of the respondents were women. According to past study, the differences between the gender seem to widen with age increase, and the gap has been found to be widest amid those in their mid to late 20s. Armstrong33 argues that gender inequalitycan be the result of a product of social functions and social expectations for male and female behaviour as it is the result of differences in biological vulnerability. This view contradicts the study conducted by Francis34 which showed that 55.4% of the respondents were male and 44.6% of the respondents were female; Ajalie35 found that male are made up of 56.8% of the entire sample size whereas 80% of female made up of 43.2% of the entire sample size.From the analysis above, it can be said that most of the respondents were males; Ahsan, et al.,36 who found that male (63.67%) and female (36.33%); Darko-Asumadu.,37 indicates that out of 115 respondents comprised of 62 (53.9%) males and 53 (46.1%) females.As a result, most of the respondents interviewed in this study were males; Afrrev38 state that respondents showed that majority of the respondents are male 55(67.3%); Xiaoyu, et al.,39 who state that most were male (54.41%) and women (45.59%) and Ade40 who state in his study that male (60.42%) and female (39.38%); Ruben,41 who state that 80.5% (132) of respondents were males and 19.5% (32) were females, suggesting that both gender were denoted in this study. Similarly, this found support with the study conducted by Sulieman & Nidaa,42 indicate that 89 (30.4%) males and 204 (69.6%) females. It follows that most of the respondents in this study were females; Adisa et al.,43 who state in his study that female respondents comprised 65% of the group and male (35%) and Annie44 who found that more than half of the respondents, 191 (59%) were females and 133 (41%) were males. Asuiefai Hospital were the largest percentage of the respondents (26.8%) in the study, followed by Gloryland Centre (25.9%) as against a minority of others such as Grand Care Hospital, Rufus Hospital Ltd and Chansmy Hospital and Maternity(3.0%). Majority of the respondents were Administrative staff (37.0%) with Marketing (0.7%) being the minority.

The largest age group was the 30-39 years old (65.2%), with those above 60 years (0.7%) being the minority. The results of the study suggest that most productive and energetic age range of 20–45 years and hence would be likely to be able to knob the associated work demands. However, these findings are consistent with the study done by Francis34 which found53.6% of the respondents in the 30–45 years age group, 33.9% in the 20–29 age group, 12.5% in the 45 years age group and above and none of the respondents were less than 20 years old. Ade40 who found that 68.75% were 26 to 45years old and the remaining 17.86% were above 46 years old and Annie44 who found that 143 (44.1%) of the respondents were in the age group 30-39 years, 119 (36.7%) were in age group 20-29 years whereas no one was above 60 years old. This was due to the stratified sampling procedure. This was done in order to minimize the effect of small cell sizes on skewing the frequency distributions. Similarly, this view is contrary to the study conducted by Ajalie35 who found that majority of the respondents were under 30 years of age, precisely 63, which represents 34.1% of the entire sample followed by 59 respondents in the age bracket of 31-40 representing 31.9% of the entire sample.38 respondents were in the age bracket of 41-50 representing 20.5% of the entire sample while 25 respondents were more than 50 years of age and represented only 13.5% of the entire sample size; Sulieman et al.,42 who indicates that 57(19.5%) are less than 25years, 162(55.3%) fell within 25 - 34 years, 64(21.8%) were aged between 35–44 years and 10(3.4%) were 45 years and above; Darko-Asumaduet al.,37 who reported that nine respondents, representing 7.8%, were in the 20-24 years old. Among the total number of respondents, 27% were between 25 and 29 years old, while 22.6% were between 30-34 years old. Of the 115 respondents, 15.7% fell within the age of 35-39 while 27% were 40 years and above.It can be deduced that the majority of employees were between the ages of 25-29 and 40 and above; Adisaet al., who state that only 12.3% were over the age of 50 years and Ruben (2014) who state that 0.6% were under the age of 25 year, 8.5% were between 25 and 30 years, 23.8% were aged between 31 and 40 years, 20.7% between 41 and 50 years, 25.6% between 51 and 60 years old and 20.7% were older than 60 years, which indicates that respondents are sufficiently matured. Moreover, this study found support with Afrrev38 who state that the respondents concentrated within the age bracket 26-41 years (79.4%).

All categories of educational levels participated in the study. The highest educational levels were university degrees (68.1%) as against a minority of respondents who had SSCE or equivalent (3.0%) who had basic level of education. This shows that the literacy level of participant was high with the majority having completed at least a university degree (68.1%) education. It is clear that most of the respondents have a Bachelor’s degree as their maximum academic qualification. Implying that most of the staff are highly educated because the healthcare occupation entails a high level of professional training. This also makes respondents for the study suitable since their level of knowledge can be considered sufficient to provide accurate and reliable information to authenticate the truth of the study. This found support with the study conducted by Francis34 showed that the majority of the respondents (42.9%) had a degree, and 28.6% of the respondents had other educational degrees and 25% of the respondents had a Master’s degree. Only 3.6% of the respondents had HND; Sulieman et al.,42 who indicates that 12(4.1%) of respondents had high secondary school and less, Diploma 83(28.3), Bachelor degrees 182(62.1%) and postgraduate 16(5.5%). However, this view is contrary to the study conducted by Ajalie35 who found that 78 respondents had an NCE/OND qualification making up 42.2% of the total number of respondents. 54 respondents have a Bachelor’s degree representing 29.2% of the total number of respondents. 45 respondents with a postgraduate degree representing 24.3% of the total respondents. 8 respondents held an O’ Level certificate which represented 4.3% of the total number of respondents; Afrrev38 who found that most of the respondents were persons with secondary school educational qualifications 22(34.9%) following by persons with primary school educational background 19(30.2%); Ade40 who found that 50% had HND/BSc as against a minority of SSCE (1.67%) level of education; Annie26 found out that 118 (36.4%) had a degree, 98 (30.2%) had diploma while 39 (12%) had certificate and Adisaet al., who state that virtually everybody within the sample completed at least 4-years of secondary education. 50 respondents reported having an undergraduate diploma, 300 had a university degree, 9 had a postgraduate education (masters), and one respondent obtained a doctoral degree. In addition, Ruben (2014) state that almost 80% of respondents had a university learning qualification, such as Bachelor degrees (25.6%), Honour’s degrees (19.6%), Postgraduate diplomas (7.9%), Master’s degrees (20.7%), and Doctorate degrees (3.0). This suggests that respondents had a good relevant educational qualification to understand and respond appropriately to the study.

A lower percentage of respondents were married or remarried (43.7%) compared to respondents who were single or never married (54.8%). This means that those participant with marital status of single are more involved than respondents from other groups, hence, the sample was a demonstrative sample of the community representation. Similarly, this view contradicts the study conducted by Francis34 who found that 53.6% of the participants are married and 46.6% of participants were single. The staff included in this study are certainly dominated by people who are married, which reflect a high demand of life needs, since married people have more responsibilities than those who are single; Ajalie35 shows that 104 participants are married, which represent 56.2% of the total population sampled, which is clearly the largest. 73 participants are single, representing 39.5% of the total participants. Only 8 participants are divorced, representing 4.3% of the entire sample size. It inferred that most of the respondents are married; Adisaet al., indicated that around 66.7% of the participants were married and Annie (2016) shows that more than half of the participants, 194 (59.9%) were married, 124 (38.3%) were single and 6 (1.8%) were divorced. However, this found support with the study conducted by Darko-Asumaduet al.,37 who indicates thatout of 115 participants, 49 (42.6%) were single and 47 (40.8%) were married.The proportion of participants who were divorced or separated from their spouses were four (3.5%), whereas the widowed were five (4.3%). It can be inferred that most of the employees were males. Majority of the respondents by ethnicity were Ijaw (34.8%) with Hausa (3.0%) being the minority. Based on experience, it shows that (58.5%) had between 1 and 5years’ experience while (1.5%) of the respondents had 16-20yrs and above 20 experience suggesting that respondents had a good blend of working experience. This view is contrary to the study conducted by Francis34 who revealed that 48.2% of the respondents had 6–10 years’ of work experience, while 28.6% of participants had 2–5 years of work experience. 12.5% have worked in hospital for 11–15 years, 7.1% have worked for more than 15 years and 3.6% of the participants have worked for less than 2 years. The results submit that 96.4% of the participants had a very good work knowledge of above 2 years; Afrrev38 who state that only about 46.9% of respondents have had between 11–20 years of knowledge, followed by 5–10 years 20 (31.7%), less than 5 years 8(12.7%)and above 20 years 6(9.5%) at the time of the survey and Adisaet al., who state that only approximately 73.5% of participants have had above 5 years of experience during the time of the study and Annie44 who found that 98 (30.2%) had worked between 5-9 years, 74 (22.8%) had worked for 1-4 years and 36 (11.1%) had worked above 15 years. Most well-known studies indicated above shows that work experience is a factor influencing performance. Inadequate experience has been known as an hindrance to reaching full autonomy of the organizational based structures.45 Numerous studies have found that as staff obtain experience, they are more probable to gain autonomy and lessen their reliance on managers.46 The experience is also linked to an increased contextual understanding of the working and improved capacity to advance innovative solutions delivery methods47 as well as a greater capacity to forestall changes and approximate project timeline.48 As a result, members of the team, who have long work experience naturally become the leaders,47 mentors,48 or coaches.49

Majority of the respondents had less than 50,000 with (1.5%) of the respondents earning above 150,000. This view is contrary to the study conducted by Annie44 showing respondents monthly earnings, that almost half of the participants, 161 (49.7%) earn 1000-1900¢, 87 (26.9%) 2000-2900¢. Only 13 (4%) earn 4000- 4900¢ and above 5000¢. Adisaet al., who state that the average monthly salary is below 2,000 BAM (more than €1,000) and most participants remained happy to report their salary range, with only 6.8% rejecting to do so, regardless of study conducted in accordance with the ESOMAR Codex for Opinion Polls, assuring full anonymity. Furthermore, majority of the respondents were senior staff (51.1%) with junior staff (48.9%) being the minority. This view found support to the study conducted by Ade40 who found that 62.92% were senior staff as against a minority of (37.08) junior staff. But contrary to the study conducted by Ajalie35 who found that the highest number of respondents was junior staffs accounting for 40% of the entire respondents. Among the 48 respondents who responded was 25.9% senior staffs whereas 34 casual staff making up 18.4% and 29 contract staffs make up 15.7%.While private hospitals have diverse individuals with different occupational training working together to safeguard the health and patient’s safety. However, participants were found to constitute other profession, which from investigations were observed to be principally administrative occupations like 1.5% of the respondents were Director, 3.7% were Manager/Assistant Manager, 14.8% were Accountant, 33.3% were Administrative Staff, 22.2% were Health Record Officer, 3.7% were Lab Attendant and 20.7% were others etc. Majority of the respondents were Administrative Staff (33.3%).This view is contrary to the study conducted by Afrrev35 who state that only about21(33.33%) of respondents are manager and others are 42(66.70) at the time of the survey. The tables above give the distributions of the gender, name of hospitals, department, age, levels of education of all respondents, marital status, ethnicity, experience, monthly income, class category and designation.

There is no significant influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals

It was hypothesized that there is no significant influence of motivation on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals. This result signifies that if there is any improvement in organizational productivity it would be mostly because of an improvement in motivation. This invariably means that an improvement in motivation will result to corresponding improvement in organizational productivity. Tella et al.,50 is of the view that although irrespective of how computerized an institution might be, productivity improvement hangs on the workers effectiveness. The ability of Workers to perform a specific task affects the organization performance. Additional package which affects performance level of employees is promotion. Higher rank promotion motivates employees to do their best. Promotion aids them to understand their workplace growth and it increase their self- esteem. Agyepon et al.,51 found that promotion, not only makes individuals ascent up the public ladder, but in utmost cases are perceived by individuals in and outside the workplace nonetheless likewise accompanied via salaries increase. In one way or the other, everyone desires to be applauded for the tasks they achieve besides this can be an inspiring motivational and powerful tool. Chandrasekar20 and Yavuz52 state that employees are given hand shake with congratulations, a pat on the back or a note of appreciation through their superiors, it demonstrates that their superiors’ value and recognize their individual contributions and the duties they perform for the organization. Recognition encourages workers efforts involve in the acknowledgement, creativity and employee’s willingness to put in additional effort. This implies that for every unit improvement in motivation, organizational productivity will increase by 0.353. This indicates that the higher the level of motivation, the better the organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospitals. However, these findings are consistent with the study done by Patrick53 who indicates that health workers performance in KATH can be enhanced by improving the motivation they provide to them. Ezigbo & Court54 argued that performance of organization is a multifaceted phenomenon that is mainly influenced by the capacity and motivation of the organization workforce. It is described that, this age of hyper universal competitiveness in the world of business, motivations are remarkably imperatives to achieving determined employee efforts, retention, employee’s commitment and industrial balance amongst organization employees. In Burke and Cooper cited in Nwokocha (2014: 86): show that when institutions motivate and value individuals, these individuals are dedicated to do well in their respective organizations as a result, the organization accomplishes more. This leads to the highest productivity of the organization. Daniel55 emphasizes on the importance of motivations in the organization. He demonstrated that implementation of motivation and appreciation can aid the quest for strategic and operational goals in an organization. He emphasizes that in a worldwide economy, as millions of small and medium scale businesses are striving for customers and organizational productivity, an organization is required to motivate and effectively compensate workers or risk dwindling behind their opponents or worse, having their workers with organization knowledge, leaving their competitors behind. Researchers have claimed that motivations aid in motivating and retaining employees competent for the performance of the organization.56 This highlights the opinions of Beer & Cannon57 and Gerhart & Rynes58 that rewards, predominantly money, may be related to desired attitude and outcomes performance to promote efficiency. Gratton58 substantiated the opinions of Gerhart and Rynes that employee’s motivation is influenced through financial and non-monetary factors. Randhawa59 contribution to monetary and non-monetary rewards provides insights into organizational setting with the aim of achieving motivation and influencing people, team and the behaviour of the organization for the attainment of strategic purposes and organizational productivity. Wang60 described that motivation in any organization is critical to building and sustaining employees’ commitment by ensuring a high productivity and standard of organizational productivity and employees’ constancy. Khawaja et al.,61 emphasize that workers are positively nearer to their firms and achieve improved jobs when workers obtain healthier organizations motivation and recognition. They further emphasize that motivations level increases employee’s proficiency and performance on their occupations and the outcome tend to surge the organization success. The performance of employees needs to be evaluated and appreciated by offering them the appropriate benefit packages, which is not only an effective method to reach organizational productivity nonetheless to ensure a persistence relationship with employees who are talented.61 Zaini et al.,63 make a connection amongst job satisfaction employee and the motivation organizations provide. According to him, job satisfaction of the employee is linked with additional monetary compensation, which include promotion, bonus and payment.

Data cited by De Vos, Annelies & Dirk64 cited in the Center for Employee Research show that 10% of workers are dissatisfied with payment as the main reason for leaving the establishments. Cappelli65 rejects this claim, arguing that the measurement criteria can make it more difficult for organizations to identify their opponents, which in turn reduces the impact of ongoing financial employee retention on reward. This shows good financial motivations and reasons for keeping employees within the organization. Luthane suggests that the use of financial resources as an organizational benefit is essential to a payments system that helps attract, retain and maintain the best employees in the organization. Lutherans asserted that organizations could afford a doctrine that could save money while becoming more productive and become efficient resources manager, while paying higher wages and better terms of benefit since they could hire and have the expertise. This is consistent with the ideas of Memoon, Kiran, and Muhammad66 that internal and external benefits satisfy employee motivation, help them stay on the team, and increase organizational productivity and performance. Likewise et al.,67 argue that an improved system of motivation can retain employees, while a less efficient system has many turnover disadvantages. However, it is noted that motivation leads to the execution of certain actions and manifests itself before the action itself, while emotional satisfaction is a state that happens after the action as described in its.68 Outcomes dissatisfaction of some act may decrease motivation in the future. Campion et al.,69 results, Richardson et al.,70 and Kaymaza71 equalized the positive motivation relationship and satisfaction, despite the different relationship directions.72–80

It can be inferred from this study that motivation had positive and significant effect on organizational productivity of private Hospitals in Bayelsa State. Therefore, this study concludes that influence of motivation in private hospitals in Bayelsa State is of great important for the productivity of the organization. Therefore, for organizations to reach prime performance they should nurture and use these unique characteristics mentioned above to achieve organizational objectives. The survey mirrored on handling the influence of motivation strategy in organizations by means of verifying its effectiveness on organizational productivity in Bayelsa State private hospital. Private hospitals in Bayelsa State should ensure that critical care is taken towards motivation, which will directly influence organizational productivity. The study reveals the dimensions required for effective motivation in private hospitals in Bayelsa State. The present study revealed very clearly in the findings that private hospitals should have a systematic approach of applying motivation for operational executives. This was statistically stated with the hypothesis statement, because hospitals are considered to be a very busy place that always keeps the employees alert all the time, this situation makes them stressful at peak times.

The study suggests that influence of organizational motivation should be considered with reinforced strategies that should be entrenched in the culture of the organization; and management need to articulate employees’ needs/preferences while developing their motivation systems. This will aid in creating a sustainable organizational policy that will promotes performance of the employee‘s, retention and organizational productivity. Likewise, private hospitals in Bayelsa State should consider adopting a flexible organizational structure in which decisions and organizational functions can be decentralized in order to achieve flexibility in process and implementation. This allows employees to easily identify their responsibilities at the management levels, appreciate processes and motivate them to execute their tasks. Furthermore, private hospital should offer recognition to its employees as a way of encouraging them to work harder and perform their duties. In this way, employees will be able to perform their duties efficiently with minimal supervision thereby reducing supervision cost. In addition, motivation plays a key role when it comes to improving organizational productivity. Given this reason, there is the need to focus on decision and self-determinism theory (as well as the sub theory of cognitive evaluation), to understand socio-emotional selectivity theory, and selective optimization and compensation theory. Practical oriented strategies that focus on these theories include: creating novel work activities and opportunities, novel learning opportunities, personalized rewards, creating open and regular conversations amongst managers and employees, and identifying high performance achievements both privately and publicly. Also, it is suggested that employers offer flexible hours of work by way of flexible work tasks.

Due to constraints of time and cost, the study limited it research to ten private hospitals and did not cover the entire private hospitals in the state. Moreover, the study focused on administrative staff (office managers) and other categories of staff performing similar administrative duties excluding the Doctors, Cleaners and Security personnel. The sample size was also limited; this can also be enlarged to find out other determinants. Furthermore, the findings of this study cannot be extended to other occupational groups in the hospital in view of varying nature of job. Hence, caution is required in generalising the result of this study. Despite these limitations, this study provides evidence regarding the relationship between eustress and organizational productivity in private hospitals and suggests that joint contribution of motivation, job rotation, job enlargement and promotion in relation to output, input, efficiency and effectiveness as measures are important for organizational productivity.

The authors express their gratitude to all participants.

Raimi Aziba-anyam Gift and Fortune Obindah equally contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. However, as primary investigator, Raimi Aziba-anyam Gift was asked to assess unclear responses of the questionnaires to determine the correct answers, whereas Raimi Aziba-anyam Gift and Fortune Obindah performed the majority of data entry.

We declare that we have no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All authors declare that ‘written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Ethical approval for the study was sought and gotten from the Institutional Review Board of the Ignatius Ajuru University of Education Postgraduate School. Permission to carry out the research, as well as written consent, was also obtained from all the selected private hospitals after explaining the purpose of the study to them. This was done by meeting the Administrative heads. Furthermore, the purpose of the study was again explained to participants before completing the self-administered questionnaire. Participants were assured of confidentiality and informed that their participation was voluntary. Participants were advised not to write their names on the questionnaire to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of the information provided. Participants were guaranteed that they may withdraw from the survey in any time, by simply not delivering the questionnaire at the end of the course session, and that all collected information would be handled anonymously and confidentially. As the questionnaire was strictly anonymous, it is implausible that individual participants could be identified based on the presented material, and ultimately this study caused no plausible harm or stigma to participating individuals.

©2020 Gift, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.