Drug delivery systems (DDS) directly affect the effectiveness of a drug's pharmacokinetics, absorption, metabolism, duration of effect and toxicity.1 DDS can be broadly classified into passive and active targeting. Passive targeting is solely dependent on Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect2,3 Active targeting on the other hand can be of two types; (i) homing to disease sites by loading targeting agents with ligands or antibodies that bind specifically to biomarkers uniquely expressed/secreted in diseased regions4 or (ii) self-propelling drug carriers.5 EPR is a direct effect of poor and leaky vasculature that is normally seen in disease sites (e.g., tumor microenvironments) and is only effective for upto 10% retention of therapeutics at these sites.6 While antibody and ligand directed nanoparticles show high levels of specific uptake by diseased cells, their targeting rates were still found to be low, as their accumulation in target sites (< 10%) is still dependent on the EPR effect.7,8 Recently, molecular communication based models were developed to optimize antibody based drug delivery systems.9,10 The current state of the art investigates various remote-controlled delivery strategies to overcome poor localization of drug carriers to disease sites. Ultrasonic waves and light directed targeting of nanoparticles to disease sites have been recently investigated and show great promise for remote-controlled DDS.11-15 Despite these promising advances, self-propelling/autonomous swimmers remain the most encouraging active DDS platforms.

Bacteria, the classic example of self-propelling/autonomous swimmers, move towards or away from external/environmental signals by a process called cheomotaxis.16,17 Anaerobic bacteria (bacteria that grow in low/no oxygen sites e.g. tumors) have been used as anti-cancer agents since Coley's experiments in 1890s.18 Since then great strides have been taken to improve and adapt bacterial DDS to a great many diseases. Currently more than 50 patents have been issued to use different strains of bacteria as anti-cancer agents.19 Bacteria are idea active targeting DDS as they can actively penetrate tissues, home in to disease sites in response to disease-specific biomarkers extruded into the extra-cellular space, and controllably induce cytotoxicity.20 More significantly, bacteria can grow selectively in disease tissue thereby compensating for poor targeting.21 Bacteria have been used to deliver anti-cancer drugs or nanoparticles and to deliver genes intracellular.22,23 Successful tumor regression studies in mice24 and other laboratory animals have led to recent FDA approved clinical trials of bacterial targeted anticancer treatments.25-27 These trials showed that patients tolerated upto 108 c.f.u/m2 of bacteria in the system without any adverse effects by either intravenous injection or intra-tumoral injection respectively. Nemunaitis27 further showed that these bacteria were able to specifically target an enzyme that could catalyze the conversion of a well known anti-cancer pro-drug to its active, killing state. However, these trials showed very poor colonization of the tumors in situ with the best-case scenario being one colony per tumor. Thus, recent research has focused on improving bacterial targeting strategies to tumor sites. Thornlow et al.28 show that increasing the motility of anerobic bacteria, Salmonella and generating homogeneous population of highly motile Salmonella, enhanced tumor penetration in vitro.

The chemo taxis capability and their effectiveness in DDS motivated the study of diffusion models for bacteria. A continuous diffusion model was developed29 to characterize the diffusion of bacterial colonies. Recent research has focused on improving bacterial targeting strategies to tumor sites. Thornlow et al.28 show that increasing the motility of anerobic bacteria, Salmonella and generating homogeneous population of highly motile Salmonella, enhanced tumor penetration in vitro. Okaie et al.30 developed a microsensor network equivalent of bacterial chemotaxis. They exploited the model in31 (later extended in32) where bacteria were modeled as microsensors and base stations were placed to monitor the different sensors.

The fact that tumor targeting bacteria not just diffuse but demonstrate sensing based motility towards the tumor33 (called "active flagellar" motion) gives rise to the need to develop stochastic models for bacterial propagation towards tumors. Some key researches on stochastic modeling of bacteria for chemotherapy are very recent34,35 and.36 Charteris & Khain34 developed a discrete stochastic lattice model to model the cells in the body as a combination of discrete lattices and the velocity of bacteria between successive lattices. The model was verified with experiments and it was shown that bacteria typically propagate only unidirectional to neighboring lattices. Lavrentovich & Nelson35 and Deng36 separately studied the time for survival of bacteria in any geographic region using diffusion model35 and by colonial communication model36,37 and showed that the time spent in any geographical region is exponentially distributed. Therefore, the propagation of engineered bacteria can be modeled as a stochastic random walk.36,37 However, the nature of these findings has not yet been exploited to analyze the time taken for bacteria to reach tumor microenvironments and determine the factors that impact this time. Wei et al37 presented simulations on first passage time to tumors. A diffusion equation was formulated that used spatial extensions to Gillespei's algorithm.38

Motivated by the findings in,34-36 we divide the region of propagation of the bacteria1 into a 3-dimensional lattice and develop a three-dimensional Markov Chain model to characterize the random walk behavior of the bacteria between the grids in the lattice. We use first passage time analysis of Markov processes2 to provide closed form expressions for the mean time taken for the bacteria to reach a desired proximity to the tumor, from the region (i.e., grid) of injection. From the first passage time analysis of Markov processes, we derive the following key results:

1While the concept of Markov models and first pass time was introduced and discussed in,36 the first pass times discussed were very crude approximations that took only the speed of the bacteria into account.

2Henceforth, throughout the paper, whenever we refer to "'bacteria", we mean "injected engineered bacteria", unless explicitly mentioned otherwise.

• The main factors that affect the tumor targeting time (time taken for the bacteria to reach the tumor microenvironment from the point of injection) are (a) the population of the injected bacteria, (b) the distance between the tumor and the region of injection and (c) the directional efficiency, defined as the ratio of the rate at which bacteria move towards the tumor microenvironment to the rate at which they move away from the tumor microenvironment.

The directional efficiency is the most significant factor that impacts time taken to reach the tumor microenvironment. While the distance between the tumor microenvironment and the region of injection also play a significant role, the population is the least effective parameter, particularly beyond a certain threshold value (called the saturation threshold of population). The results obtained from out model matches well with existing experimental results28 that measure the time taken by control bacteria to reach the tumor microenvironment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research that characterizes the first passage times of injected bacteria reaching the tumor microenvironment, to clearly bring out the dependencies on the population, directional efficiency of the bacteria and the distance between the region of injection and the tumor. Our analysis can be extended to these scenarios at the cost of additional computational complexity.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 5 defines the objective of this research and builds the Markov model. Numerical results are described in Section 6 and conclusions are drawn in Section 7.

Consider a finite population of engineered bacteria injected into a medium (e.g., blood stream), bound for a tumor. Initially, at the point of injection, the bacteria are unaware of the exact location of the tumor thus they propagate according to a random walk model.34-37 Once the bacteria reach the tumor microenvironment, they then move towards the tumor, by active chemotaxis in response to chemical signal from the tumor17,29 and grow according to the model discussed in.33 The objective is to estimate the mean time taken by the bacteria to reach the tumor microenvironment from the point of injection. For this, we develop a Markov model that characterizes the random walk behavior from the point of injection to the tumor microenvironment. We first describe the basic system model and the assumptions we make, in Section 5.1 and the Markov model in Section 5.2.

System model

We divide the medium into set of rectangular lattices in three-dimension based on the lattice model in.34 For simplicity, a two dimensional equivalent is shown in Figure 1. The lattice division shown in Figure 1 is only notional and does not depict a real-life representation of the medium. The grids shown in Figure 1 only represent a region where a bacterium might be present at any instant of time3 Later, from . We make the following model description to facilitate the problem definition and the related analysis.

3Later, from Theorem 2.1, it will be observed that the dimensions of the gird and the number if such grids do not affect the time taken to reach the tumour microenvironment.

Figure 1 A grid representation of the bacterial propagation region. For simplicity a two-dimensional picture is shown. In our model we use 3-dimensional lattice.

Bacteria can move only to one of four neighbouring cells (either in the vertical or horizontal direction but not diagonally.34 The region, (0; 0), represents the point at which the bacteria is injected and (m;m) represents the tumor microenvironment.

- The bacteria is injected in a region labeled by the gird (0, 0, 0) in three dimensions (the gird, (0, 0) in the two-dimensional representation shown in Figure 1). Irrespective of where the bacteria are physically injected into the body, we consider the region of injection to be represented by the gird, (0, 0, 0).

- The negative indices for the grids represent regions that are opposite in direction from the region of injection with respect to the tumor microenvironment. In general, the negative indices can go up to -of, but for purposes of computation and tractability, we limit them to -m. It is noted that since the negative indices represent propagation away from the desired target region, the values of negative indices are not relevant for our analysis, as will be observed later from (8).

- The grid, (m, m, m) (or the grid, (m, m) in the two dimensional representation shown in Fig. 1) depicts the tumor microenvironment. This does not represent the actual tumor. It only represents the outer bounds of the of the region surrounding the tumor beyond which chemical signals from the tumor do not reach. Within the bounds of the tumor microenvironment (past grid (m, m, m) or (m, m) in Figure 1) the bacteria propagate to the tumor by chemotaxis.17,29

- Note that although we have shown the regions to be of uniform size, they are not so in practice. However, the variations in the sizes of the individual regions can be easily incorporated by suitably changing the number of regions, m.

- Until the bacteria reach the grid (m, m, m) (or (m, m) in the two-dimensional representation shown in Figure 1), they follow a random walk behavior.34-36

- The objective is to develop a stochastic model that can be applied to determine the mean time taken to reach the tumor microenvironment from the region of injection, i.e., the time taken to reach grid (m, m, m) starting from grid, (0, 0, 0). This model should provide: the parameters that affect the mean time taken to reach (m, m, m) starting from (0, 0, 0) and - the factors that are more dominant, i.e., that have more significant effect on the mean time, compared to other factors.

Markov model

Until, the bacteria injected in region depicted by the grid (0, 0, 0) reach the tumor microenvironment, i.e., until the bacteria reach the region, (m, m, m), they move according to a random walk process36,37 by spending a random time in each of the regions shown in Figure 1. The random time is exponentially distributed.35 Therefore, we model the random walk behavior of the bacteria from the region of injection (0, 0, 0) until it reaches (m, m, m) as a three-dimensional continuous time Markov chain (3D-CTMC). In general, a bacteria in grid (n,k, l)

, can move to a grid (n,k, l), where

Based on the finding in,34 the velocity or motility in the diagonal directions (i.e., when

and

was zero. Hence, bacteria can only move to the regions to the left, right, up or down. In a three dimensional lattice, the six possible directions a bacteria can move to would be left, right, front, back, up and down. For simplicity, in Figure 2, we show the state diagram for a 2D-CTMC assuming that the region is split into an m x m grid in two-dimensions as shown in Figure 1. Let (n; k; l) represent any state of a CTMC, i.e., represents the region at which a bacteria is present. The transition rate,

represents that rate at which the CTMC transits from state, (n, k, l) to state, π

Then.

(1)

otherwise

Figure 2 Two dimensional equivalent of the 3D CTMC model for random walk behavior of bacterial propagation.

The negative signs indicate grids away from the direction of the tumor, relative to the region of injection.

.

This constitutes a three dimensional birth-death process. Since the movement of the bacteria follows a random walk, the direction of transition from any state to its neighboring state is independent of the direction of the previous transition. Therefore, the steady state probability of being in state (n,k,1), 7rnki, is obtained by applying the analysis in39 as

(2)

Where

is the rate of transiting from state

to

and

is the rate of transiting from

to

(

and

are also defined similarly). The factor, G, in (2) is a normalization factor, so that

. For 3-D equivalent of the transition diagram shown in Figure 2,

i.e.,

(3)

The ratio,

is the ratio of the rate at which the bacteria move towards the tumor to that at which they move away from the tumor, i.e., the directional efficiency of the bacteria. The average time taken to reach the region (m, m, m) starting from state, (0, 0, 0) is obtained by first-pass time analysis of a birth-death process. Let

(m) represent the average time taken for the CTMC to reach (m, m, m) starting from state, (0, 0, 0). Let

(m, 0, 0)4 represents the average first pass time to reach state (m, 0, 0) from state (0, 0, 0) in a one dimensional birth-death process. Formally,

(m, 0, 0) can be written as

(4)

where

(t) is the grid in which the bacteria are present at time, t. The Laplace transform of

(1; 0; 0)

is denoted by

, given by40

(5), which can be solved recursively. Then,

(6)

Since the transition rates from any state, (n, k, l) to (n+1, k, l), (n, k+1, l) and (n, k, l+1) are all equal to

5

(7)

4

and

can be similarly defined.

5Similarly, transition from state, (n,k, l) to states, (n -1, k, l), (n, k -1, l) and (n, k, l- 1) are all equal to

Using the fact that the movement of the bacteria follows a random walk, i.e., the direction of transition from any state to its neighboring state is independent of the direction of the previous transition,

(8)

from (5)-(7). It is observed that the first pass time depends on m. This implies that the time taken for the bacteria to reach the tumor microenvironment is a function of the number of lattice grids the region of propagation is divided into. Note that the number of lattice regions, m, also impact the transition rates,

and

since they are dependent on the average motility of the bacteria and the size of individual regions. The following theorem helps us remove the dependence on m.

Theorem 2.1: When the directional efficiency and the number of grids are large, the first passage time to the tumor does not depend on the number of grids.

Proof: From (8),

which simplifies to

4

When p > 1 (i.e., when the directional efficiency of the bacteria is large), the above simplifies to

(9)

which is independent of m. Note that from Figure 2, the number of grids in three dimensions is

Since,

is independent of m from (9), it is independent of the number of grids,

.

If the bacteria travels at velocity or motility, v, the distance between the region of injection of the bacteria and tumor microenvironment is d and the cell diameter is c, then

i.e.,

and

which is independent of m. Also, if the approximation is ignored,

and µ vary with m at the same rate and hence the ratio

becomes independent of m. Therefore, the approximate time to reach the desired region is independent of the size of the lattice, m. However, if bacteria move in groups of population of size, g, then

where

is the rate of each individual in the group and

is inversely proportional to g, indicating that as the population size increases, the time taken to reach the tumor microenvironment decreases.

For the numerical computations, we consider cell diameter of 1.1 pm34 and bacterial motility of 2.5

to 37.5

,28 i.e., about 2 to 34 cell diameters per second. This results in a

to

where d is the distance between the point of injection and the tumor microenvironment, expressed in microns. For a population of size, g,

as mentioned in Section 5.2. We compute the average time taken to reach the tumor microenvironment, as a function of the motility of the bacteria. We consider three cases,

- The directional efficiency,

i.e., bacteria is twice as fast to move away from the tumor microenvironment as towards the tumor microenvironment.

- p = 1, i.e., the bacteria is equally likely to move away from the tumor microenvironment as well as towards the tumor microenvironment.

- p = 2, i.e., the bacteria is twice as fast to move towards the tumor microenvironment as away from the tumor microenvironment.

For each case above, we measure the average time taken to reach the tumor microenvironment from the region of injection, when the distance, d, from the region of injection to the tumor microenvironment (i) d = 100

, (i) d = 1000

and (iii) d = 10000

. Figures 3- 5 depict the first passage time results for

and 2, respectively.

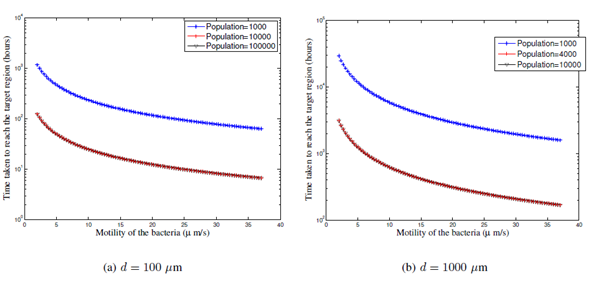

It is observed from Figures 3-5, that there is a threshold population size (called saturation threshold) beyond which, the increase in population size is ineffective. From Figure 3, it is observed that when

, for an order of increase in d, there is an order of increase in the time taken to reach the tumor microenvironment from the region of injection, e.g., from 15 hours for d = 100

(see Figure 3a) to 150 hours for d = 1000

(Figure 3b) and to 1250 hours for d = 10000

(Figure 3c) for a motility of 25

s-1).

The saturation threshold is larger for smaller distances (= 10000 for d = 100 pm) while it reduces as d increases (= 4000 for d = 1000

and = 2500 for d = 10000

). This indicates that if distance between the region of injection and the tumor increases, and then increase in population does not impact the first passage time to reach the tumor microenvironment. This is because, larger population is effective for smaller d because even when a subset of the population reaches the tumor microenvironment, it can draw the rest of the population towards the tumor microenvironment. However, when the distance, d, is large, the entire population is still far away from the tumor microenvironment, thereby negating the effect of population.

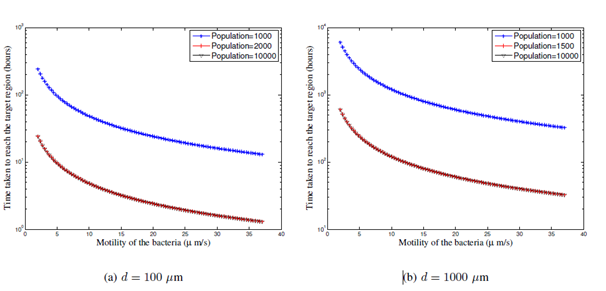

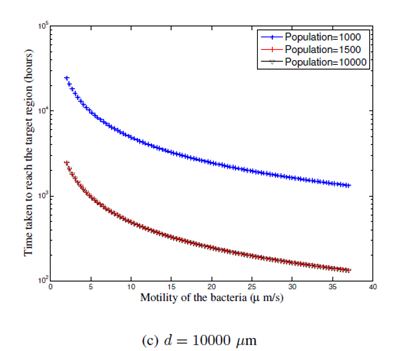

When the directional efficiency becomes larger i.e., when p = 1 (see Figure 4), the saturation threshold decreases, e.g., = 2000 for d = 100

(from Figure 4a) and = 1500 for d = 1000 (Figure 4b

and d = 10000

(Figure 4c). This is because, when the rate of going towards the tumor and away from the tumor are same, even a smaller population of bacteria find their way to the tumor and a larger population is not necessarily required. When p = 1, it is observed that an order of increase in d results in an increase in the first passage time by a factor of 4 to 5 (increase from 8 hours for d = 100

to 30 hours for d = 1000

and to 150 hours for d = 10000

for a motility of 25 pms-1). Since the directional efficiency, p, increases, the bacteria find their way to the tumor better than when p = even when the distance between the region of injection and the tumor increases. The numerical values we obtain match well with existing experimental results in28 that show that control bacteria reach the tumor growing edge in about 8 hours, in vitro, where the distance between the injection site of bacteria and tumor edge is about 150

.

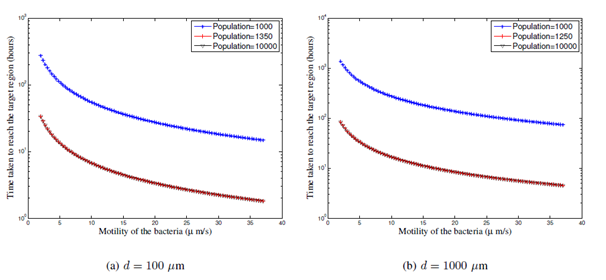

The saturation threshold decreases further then the directional efficiency, p = 2, as seen in Figure 5. The values are 1350 for d = 100

from Figure 5a) and 1250 for d = 1000

and d = 10000

from Figure 5b and 5c. When p = 2, an order of increase in the distance from the region of injection to the tumor microenvironment results in an increase in the first passage time by a factor of 2 to 4 (increases from 2 hours for d = 100

to 8 hours for d = 1000

and 16 hours for d = 10000

for a motility of 25 pm s-1. A directional efficiency of p = 2 > 1 implies that even for large distances, small population of bacteria are twice as fast towards the tumor microenvironment than away from the tumor microenvironment, thereby leading to a reduction in the factor of increase in the first passage time and a reduction in saturation threshold.