MOJ

eISSN: 2374-6920

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 5

Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), USA

Correspondence: Margaret Simonian, David Geffen School of Medicine, Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), 611 Charles E. Young Drive East, CA. 90095, USA, Tel +13107947308

Received: September 22, 2015 | Published: November 16, 2015

Citation: Simonian M. Cerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs): causes, treatment and research. MOJ Proteomics Bioinform. 2015;2(5):158-160. DOI: 10.15406/mojpb.2015.02.00061

This work describes an overview of brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) causes, current treatment methods, and the research conducted in this field to better understand the biology and pathophysiology of these vessels, and to develop novel therapies, especially for a subset of AVMs that are not treatable with current treatment methods.

Keywords: pathophysiology, AVMs, endothelial cells, arteries; veins

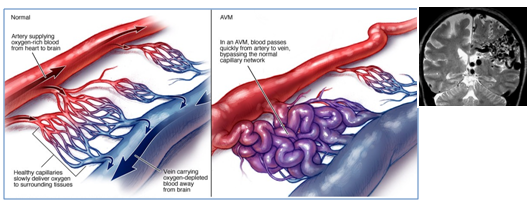

Brain AVM is a tangle of abnormal blood vessels (arteries and veins) (Figure 1), this abnormal collection causes blood to flow quickly and directly from the arteries to the veins, therefore, AVM vessels have a higher rate of bleeding compared to normal vessels. Ruptured AVMs are the main cause of haemorrhagic stroke in children and adults.1 The cause of brain AVMs remain unclear; some researchers believe that it may be caused by a rupture of blood vessels during foetal development while others suggest that they develop postnatally, undergoing a growth during childhood or early adulthood, this growth may be caused by venous hypertension or by shear stress that trigger growth factor expression by endothelial cells lining the AVM fistula. AVMs are not inherited, with the exception of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) condition. AVM is not a cancer and does not spread to other parts of the body.2 Brain AVM can occur in any region, and range in size from 3-6 cm. According to Spetzler-Martin AVM grading system, they are graded from (I-V), based on their size, location and treatment risk .3 One third of AVMs are high grade (IV-V), 90% of those are not treatable, and 25% of grad (III) AVMs are not treatable without high risk.4

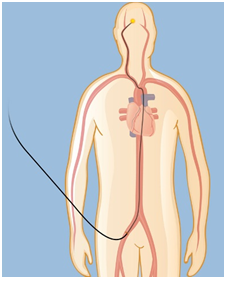

Treatment of AVM is important to prevent bleeding (haemorrhage). The risk of bleeding is 4% per year; each haemorrhage carries a high risk of permanent disability or death.5,6 Treatment will also relive the symptoms associated with AVM, such as headaches, seizures and increasing paralysis. Current treatment options are; surgery, embolization, and stereotactic radiosurgery. Small AVMs that are located on the surface of the brain are suitable for surgical removal, however the risks of surgery is high with large AVMs and the AVMs that are located in the deep parts of the brain.3 Embolization is performed under X-ray direction. A small catheter is inserted through the artery in the groin and navigated to the brain arteries,4,7 (Figure 2). This procedure itself is not usually a cure; often combined with other treatments such as radiosurgery or surgery.7 Stereotactic radiosurgery is suitable for small AVMs; with this method a focused x-ray beam or gamma-rays are delivered to the AVM such that a high dose is concentrated on the AVM with a much lower dose delivered to the rest of the brain (Figure 3). This irradiation causes AVM vessels to be occluded; however this process may take 2-3 years to complete in most patients, while the risk of bleeding still persists.

To develop novel therapies for currently untreatable AVMs, researchers have been studying the genetics, pathophysiology and the molecular process of AVM vessels. Animal models have also been developed to better understand the biological and hemodynamic characteristics of human brain AVMs, such as the swine model developed by Massoud TF,8 the sheep model by Qian et al.,9 the dog model by Pietila et al.,10 in 2000 and the rat model by Morgan et al.,11 in and Yassari et al.12 To develop gene therapy, genetic studies suggested that HHT are caused by mutations in either endoglin (ENG) gene or activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ACVRL1) gene, both are associated with TGFβ/BMP signalling. Mutation in the co-receptor ENG is associated with HHT1, while HHT2 is associated with mutations in the signalling receptor ACVRL1.13

Endothelial cells lining the AVM vessels and their response to irradiation have also been studied14–16 and thrombosis was stimulated in the animal model of AVM after irradiation using non-Ligand targeting agents,17–19 however this approach had limitations. To develop a ligands based vascular targeting therapy, subsequent studies proposed that radiosurgery alter AVM endothelial surface molecules that allow discrimination from normal endothelial cells. These molecules then can be used for a Ligand-directed vascular treatment to stimulate rapid thrombosis (occlusion) in AVM vessels. To identify potential targets for the AVM molecular therapy, proteomics studies have been employed in the past few years to identify protein targets on the surface of AVM endothelium post radiosurgery. These target proteins will be employed for the Ligand-directed treatment to promote rapid thrombosis in AVM vessels.20–22 This is especially important for patients who currently have to wait 2-3y after radiosurgery for their AVM to be completely occluded. To achieve this goal, in vitro and in vivo biotinylation methodologies were developed by Simonian et al.,20 and employed to label membrane proteins in the murine cerebral endothelial cell culture and in the animal model of AVM post irradiation.20 Membrane proteins were then identified using quantitative proteomics techniques, iTRAQ and MSE and data analysis software’s such as ProteinPilot and ProteinLynx Global Server (PLGS). Example of identified potential proteins targets were, PECAM-1, cadherin-5, PDI, integrin alpha-5, and integrin beta-1.20-22 The target proteins identified are currently being investigated in the animal vascular targeting trials, and will further be investigated in human targeting trials in the future.22

New effective treatments are needed for currently untreatable AVMs. Proteomics plays an important role in medical research, because of the link between proteins, genes and diseases; hence, identifying unique protein expression associated with diseases is a very important and promising area in the field of clinical proteomics, and in developing targeted therapies for brain AVMs. Bioinformatics tools are also necessary to analyse and interpret the biological datasets.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2015 Simonian. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.