MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2919

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 5

1Department of Veterinary Medicine, Kâhta Vocational School, Adıyaman University, Turkey

2Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Çukurova University, Turkey

Correspondence: Mustafa Güçlü Sucak, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Kâhta Vocational School, Adıyaman University, Turkey

Received: October 21, 2024 | Published: November 8, 2024

Citation: Sucak MG, Göncü S. The effect of lying behaviour on rumination in Holstein dairy cows. MOJ Eco Environ Sci. 2024;9(5):236-239. DOI: 10.15406/mojes.2024.09.00331

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between lying behaviour and rumination frequency in Holstein breed dairy cows. The study was carried out on a dairy farm with a capacity of 200 milking cows (total of 420 cows)using a continuous observation method with researchers positioned at four fixed points around the barn. Monthly analyses of rumination frequency in milking cows revealed an average of 60.66 ± 2.32 ruminations in March (range: 37–125), 60.19 ± 2.22 in April (range: 37–82), and 60.19 ± 1.17 in May (range: 37–125). As a result of the study, the number of ruminations of the standing group was 58,85±2,06 times with a minimum of 37 and a maximum of 125 times, while the number of ruminations of the lying group was 61,33±1,29 times with a minimum of 39,00 and a maximum of 100,00 times. The differences between the average ruminations of standing and lying cows were not statistically significant. The observed rumination frequencies were within the range considered normal for healthy dairy cows.

Keywords: rumination, dairy cow, seasons

Lying behaviour in cows is a critical factor as it is directly related to their overall health and productivity. There are many factors affecting lying behaviour, but lying also affects productivity and welfare For this reason, it is necessary to organize herd management by taking into consideration the factors that are effective in the enterprise that affect lying. Studies have shown that milking cows prefer to lie on dry bedding1–3 and daily lying time is reduced on wet ground.4 When cows are lying down, blood flow reaches the mammary glands more easily and this has a positive effect on milk production.5 Pereira and Heins6 reported that cows reared in the organic low-input conventional system had a lower rumination time during the summer months (June, July and August). Sjostrom et al.7 reported that daily rumination was 509 min per day for cows housed indoors and 530 min per day for cows housed outdoors and was higher in cows housed outdoors.

Prendiville et al.8 reported that 108 Holstein cows on pasture chewed more than Jersey cows. However, when evaluated per unit of body weight, Jersey cows chewed more and chewed more than Holstein cows. Aikman9 reported that Holsteins chewed more time per day than Jerseys; however, when considered per unit of feed ingested, Jerseys chewed for more time.

Ruminating, which functions to physically break down roughage to facilitate its passage from the rumen to the small intestine, is the hallmark of the bovine digestive system. Ruminating has been defined as ‘the process by which nutrients are brought from the rumen back into the mouth by vomiting, chewed again, mixed with saliva and swallowed and the material is returned to the rumen’.10 During rumination, the particle size of the food is reduced and the particles pass into the reticulo-omasal opening. This passage is also affected by the changing particle shape, density and digestibility during the rumination process.11 During rumination, the chewing activity stimulates the secretion of saliva, which facilitates swallowing and contributes to the bicarbonate and phosphate content, which helps to maintain the rumen pH at a constant level (5.5-6.5) favourable for rumen microbial activity.12 The liquid in the bolus is squeezed with the tongue, chewed again and then swallowed again.12

In this study, it was aimed to investigate the effect of lying behaviour on rumination in Holstein breed dairy cows.

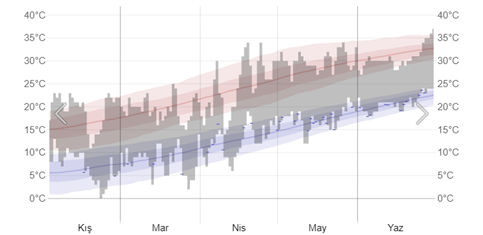

This study was conducted in Adana, in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (Figure 1) and subtropical climatic conditions, between March and May in 2021. Adana has a typical Mediterranean climate. Winters are mild and rainy and summers are hot and dry (Figure 2).

In the farm, milking is carried out twice a day in the morning and in the evening at 12 hours intervals in the central milking parlour (Figure 3) with an automatic milking system. Milk yields of the animals are kept daily by the milking system automation during milking. The milking system is also programmed to monitor the feed consumption and milk yield of the cows and to report about the angry cows. During milking, the cows were pre-cleaned and the teats are attached to the cows and when the milk flow rate decreases, they are monitored and removed by the milkers.

Total mixed ration (TMR) feeding system is applied in the enterprise and the ratio of mixed feed: roughage in TMR composition is 60:40. Cows are fed with total mix ration containing maize silage, alfalfa, wheat straw and concentrate (18% crude protein and 2650 kcal/metabolic energy (ME)/kg). The composition of the roughage in the total mixture ration is composed of maize silage (50%), alfalfa hay (25%) and wheat straw (25%). In this ration, 22 kg silage, 2 kg straw, 2kg dry alfalfa hay, 2 kg dry clover (Total: 26 kg roughage) and 4 kg concentrate feed, 4 kg crushed feed (Total: 8 kg concentrate feed) and 4.5 kg milk feed (pellet feed) according to milk yield are given by automatic feeders. Total mixture rations are prepared daily and given to animals as two meals at 07.00 in the morning and 16.00 in the afternoon.

Cow behaviour was recorded by continuous observation by researchers standing stationary at four different sides of the stall. Investigators were stationed on all four sides of the barn with the cows controlled and remotely selectable in such a way that all behaviour of a given animal could be easily recorded and the presence of the observer had no effect on the routine and behaviour of the cow (i.e. the animal did not change its behaviour or move away from the observer). The number of ruminations of lying and standing animals were recorded and evaluated for 3 months, 3 times consecutively and once a month for 3 days.

The data obtained in the study were arranged with Excel programme and evaluations were made using SPSS 20 statistical package programme.

The distribution of rumination numbers of lying and standing cows determined in the research is summarized in Table 1.

|

Dependent variable |

Months |

Behaviour |

Mean |

Std. Error |

|

Observation day1 |

March |

Standing |

60,069 |

2,693 |

|

Lying |

61,476 |

3,165 |

||

|

April |

Standing |

62,385 |

2,844 |

|

|

Lying |

62,125 |

2,960 |

||

|

May |

Standing |

50,875 |

3,626 |

|

|

Lying |

60,769 |

2,322 |

||

|

Observation day2 |

March |

Standing |

50,069 |

2,693 |

|

Lying |

51,476 |

3,165 |

||

|

April |

Standing |

52,385 |

2,844 |

|

|

Lying |

52,125 |

2,960 |

||

|

May |

Standing |

40,875 |

3,626 |

|

|

Lying |

50,769 |

2,322 |

||

|

Observation day3 |

March |

Standing |

70,069 |

2,693 |

|

Lying |

71,476 |

3,165 |

||

|

April |

Standing |

72,385 |

2,844 |

|

|

Lying |

72,125 |

2,960 |

||

|

May |

Standing |

60,875 |

3,626 |

|

|

Lying |

70,769 |

2,322 |

||

|

Average |

March |

Standing |

60,069 |

2,693 |

|

Lying |

61,476 |

3,165 |

||

|

April |

Standing |

62,385 |

2,844 |

|

|

Lying |

62,125 |

2,960 |

||

|

May |

Standing |

50,875 |

3,626 |

|

|

Lying |

60,769 |

2,322 |

Table 1 Observation day, months, number of ruminations of lying and standing groups

As a result of the analysis of variance, the number of ruminations of the standing group was 58,85±2,06 times with a minimum of 37 and a maximum of 125 times, while the number of ruminations of the lying group was 61,33±1,29 times with a minimum of 39,00 and a maximum of 100,00 times (Table 2). The differences between the average number of ruminations of standing and lying cows were not statistically significant (Figure 4).

|

|

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

Standing |

71 |

588,451 |

1,734,741 |

205,876 |

37,00 |

125,00 |

|

Lying |

84 |

613,333 |

1,186,605 |

129,469 |

39,00 |

100,00 |

|

Mean |

155 |

601,935 |

1,463,633 |

117,562 |

37,00 |

125,00 |

|

Significiancy |

|

NS |

|

|

|

|

Table 2 Average rumination counts of standing and lying cows

As a result of the variance analysis, when the differences between the number of ruminations of the cows according to the months were analyzed, it was found that the number of ruminations of the milking cows was 60,66±2,32 times in March, with a minimum of 37.00 and a maximum of 125.00, while the number of ruminations was 60,19±2,22 times in April, with a minimum of 37.00 and a maximum of 82.00. In May, the number of ruminations was 60,19±1,17 times with a minimum of 37,00 and a maximum of 125,00 (Table 3). The differences between the mean number of ruminations of cows according to the months were not statistically significant.

|

Months |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

March |

50 |

606,600 |

1,644,361 |

232,548 |

37,00 |

125,00 |

|

April |

50 |

622,600 |

1,573,480 |

222,524 |

38,00 |

125,00 |

|

May |

55 |

578,909 |

1,146,116 |

154,542 |

37,00 |

82,00 |

|

Total |

155 |

601,935 |

1,463,633 |

117,562 |

37,00 |

125,00 |

|

Significancy |

|

NS |

|

|

|

|

Table 3 Average rumination numbers of cows according to months

The average number of rumination of cows according to the observation days is given in Table 4. As a result of the analyses, the average number of ruminations of milking cows was determined as 58,84±2,05 times with a minimum of 37 and a maximum of 125 times on the 1st observation day, 48,84±2,05 times with a minimum of 27,00 and a maximum of 115,00 times on the 2nd observation day and 68,84±2,05 times with a minimum of 47,00 and a maximum of 135,00 times on the 3rd observation day (Table 4). The differences between the mean number of ruminations of the cows according to the months were not statistically significant.

|

Behaviour |

Observation day 1 |

Observation day 2 |

Observation day 3 |

|

|

Standing |

Mean |

588,451 |

488,451 |

688,451 |

|

Median |

580,000 |

480,000 |

680,000 |

|

|

Std. Error of Mean |

205,876 |

205,876 |

205,876 |

|

|

Minimum |

37,00 |

27,00 |

47,00 |

|

|

Maximum |

125,00 |

115,00 |

135,00 |

|

|

Lying |

Mean |

613,333 |

513,333 |

713,333 |

|

Median |

600,000 |

500,000 |

700,000 |

|

|

Std. Error of Mean |

129,469 |

129,469 |

129,469 |

|

|

Minimum |

39,00 |

29,00 |

49,00 |

|

|

Maximum |

100,00 |

90,00 |

110,00 |

|

|

Average |

Mean |

601,935 |

501,935 |

701,935 |

|

Median |

600,000 |

500,000 |

700,000 |

|

|

Std. Error of Mean |

117,562 |

117,562 |

117,562 |

|

|

Minimum |

37,00 |

27,00 |

47,00 |

|

|

Maximum |

125,00 |

115,00 |

135,00 |

|

Table 4 Average rumination numbers of cows according to observation days

Ruminant behaviour of cattle has been the subject of many studies. Researcher3,10 reported that there is a daily pattern in rumination and that cattle normally ruminate for 8-9 hours a day. However, Lindgren13 stated that the daily rumination pattern varies depending on feeding frequency, feeding time and ration composition. It is also reported that when the animal is disturbed, it will stop ruminating. The researcher states that stress conditions such as pain, hunger, maternal anxiety or illness can cause a decrease in rumination time (Figure 5) (Figure 6). Lindgren13 states that ruminant activity occurs primarily at night and during rest periods in the afternoons. Sjaastad et al. (2003) stated that cattle ruminate for 25-80 minutes per 1 kg of roughage consumed. Adin et al.14 reported that adult dairy cows ruminate for 7-8 hours per day. Soriani et al.15 reported that the average rumination time of dairy cows in healthy and stress-free conditions was 463 min/day in heifers and 463 min/day in multi-birth cows.

Figure 6 Climatic data for March, April and May 2021, when the study was conducted (General Directorate of Meteorology, 2024).

Schirmann et al.16 examined the feeding and rumination behaviour of 42 Holstein dairy cows in the early dry period and stated that rumination time was affected by feed intake and ration structure. Adin et al.14 reported that diets containing 11.7% NDF resulted in 12.7% less rumination time than diets containing 14.1% NDF, and there was a 23.5% increase in RT per kilogram of roughage consumed. Beauchemin and Yang17 also stated that rumination increased linearly with the physically effective NDF in the diet.

Pereira and Heins6 stated that Holstein cows ruminate more than crossbreds as a result of a 4-year study and the reason for this was the difference in body size. However, Gregorini et al.,18 in their study with 320 milking cows, stated that the daily rumination time is related to age, but not to the breed or genetic structure of the cow.

Studies have tried to evaluate rumination in different aspects such as time of day, time of day or total rumination time. Healthy cattle spend 40-50% of the day ruminating. Each rumination is repeated 50 to 70 times.19 A decrease in the duration and number of ruminations necessarily indicates the presence of a problem. In this study, the number of rumination was found to be within the limits considered normal.20–22

Ruminating in cows is important for animal health, herd management, and welfare. Rumination is a part of cows' digestive process and indicates rumen health and ration quality. As a result of the study, the number of ruminations of the standing group was 58,85±2,06 times with a minimum of 37 and a maximum of 125 times, while the number of ruminations of the lying group was 61,33±1,29 times with a minimum of 39,00 and a maximum of 100,00 times. The differences between the average ruminations of standing and lying cows were not statistically significant.

None.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest in writing the manuscript.

©2024 Sucak, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.