MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2919

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 1

1Department of Biological Sciences, Covenant University, Nigeria

2Biotechnology Centre, CUCRID building, Covenant University, Nigeria

3Department of Biochemistry, Covenant University, Nigeria

4Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Correspondence: Jacob O Popoola, Department of Biological Sciences, Covenant University, Biotechnology Centre, CUCRID building, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria, Tel 234(0)8064640018

Received: December 04, 2018 | Published: January 7, 2019

Citation: Popoola JO, Egwari LO, Bilewu Y, et al. Proximate analysis and SDS-PAGE protein profiling of cassava leaves: utilization as leafy vegetable in Nigeria. MOJ Eco Environ Sci. 2019;4(1):1-5. DOI: 10.15406/mojes.2019.04.00125

Introduction: Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is an important starchy food crop whose leaf is yet to be adopted and utilized as leafy vegetable and as potential protein source for monogastric animals in Nigeria. Providing more nutritional information and highlighting health benefits could encourage consumption, hence this study.

Methodology: Twelve varieties of cassava were collected from farmers and Genetic Resources Centre of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Total protein content was estimated in supernatant using BSA as standard. Moisture, dry matter, protein, crude fat, ash, sodium and potassium contents were determined using standard protocols.

Results: The proximate analysis show that crude protein percentage ranged from 11.81 in variety OsNo001 to 22.75 in variety IBA30572. Moisture content varied from 8.09 in OsNo001 to 10.90 in IBA011371 while ash content varied from 6.88 in IBA010040 to 9.64 in variety 1089A. Four varieties IBA950289, IBA980505, TMEB91934 and 1089A have richer proximate content in ash, protein, carbohydrate, and fat contents. The result of SDS-PAGE indicates the presence of proteins in all the cassava leaves analyzed. The SDS-PAGE cluster analysis generated four major cluster groups suggesting the presence of four types of protein.

Conclusion: The cassava leaves are comparable to known leafy vegetables Amaranthus in nutritional and biochemical contents. It is evident that the protein content might be sufficient enough to adopt cassava leaves as a leafy vegetable based on the SDS-PAGE. Thus, the cassava varieties are good candidates for utilization as leafy vegetable to augment the exotic and known leafy vegetables in Nigeria.

Keywords: cassava, leafy vegetable, SDS-PAGE, protein content and profile

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is increasingly propagated in Nigeria as a major source of staple food, income and other derivable end-products. It is considered rich in carbohydrates, vitamins and mineral nutrients and carotenoids.1 The essential amino acid profile is also comparable to legumes such as soybean and to the recommended reference protein intake.2,3 Valuable phytochemicals as natural antioxidant components have also been linked to cassava leaves.4,5 Diets rich in nutritional contents are reportedly capable of reducing risk of many chronic diseases.6–8 Vegetables are considered therapeutic and enhances rate of digestion, excretion and regulates blood pressure levels.9,10 Several authors had confirmed the nutritional potentials of cassava leaves as alternative leafy protein resource for both humans and animals.2,11

Despite the huge potentials of the crop, its leaves have not been incorporated into food system as leafy vegetable and as alternative protein source for monogastric animals in Nigeria. The leaves usually waste after harvest, which if properly harnessed and well processed could serve as alternative or supporting leafy vegetable, thus diversifying its utilization potential. In Sierra Leone and elsewhere, cassava leaves are commonly utilized as leafy vegetable in homes and as animal feeds.2 In addition, protein contents are important for body growth and proper cell functioning, hence determination of protein contents, proximate composition and protein profiling of the cassava leaves will enhance its utilization. It is also envisaged that utilization of cassava leaves as leafy vegetable will amount to balancing the nutritional quality of proteins, fibre, minerals and vitamins content with the carbohydrate and thus, achieving a maximum nutritional use. One of the commonly engaged technique for estimating the molecular weights of proteins is Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).12,13 It is based on the dissimilarities within and between test samples which offers good estimate of the protein profile of the samples. The present study therefore, explores the proximate composition and SDS-PAGE leaf protein profiling of 12 varieties of cassava. It is aimed to validate the existing information on cassava, recommend the leaves as leafy vegetable and as potential source of leaf protein for monogastric animals in Nigeria.

Cassava leaf samples processing and proximate composition of cassava leaves

Leaf samples of 12 varieties of cassava were harvested from the Cassava experimental farm of Covenant University, Ado-Odo, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria (latitude 6˚37'N, longitude 3˚42'E and altitude 41m). The variety numbers and sources of planting materials used for this study are shown in Table 1. The harvested leaves were weighed, washed and processed using the procedure described by Oresegun et al.14 The 12 varieties were subjected to proximate composition analysis of protein, moisture, ash, crude fibres, fat, and carbohydrate.15 Micro-Kjeldahl method was used to determine the nitrogen content percentage.

Variety |

Source |

Type |

Name |

Area |

L/G |

State |

IBA010040 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

IBA950289 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

IBA980505 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

IBA011568 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

IBA011371 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

IBA980581 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

IBA30572 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

TMEB419 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

TMEB91934 |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

1089A |

IITA |

Breeding line |

NA |

IITA |

Akinyele |

Oyo |

OsNo001 |

Farmer |

Landrace |

Oko Iyawo |

Ipetumodu |

Ife North |

Osun |

OsNo002 |

Farmer |

Landrace |

NA |

Akinola |

Ife North |

Osun |

Table 1 Variety numbers and sources of planting materials used for this study

Protein extraction

Leaf protein extraction was achieved in an extraction buffer (50mM Tris HCl), centrifuged at 14,000rpm: 18˚C for 25min. The protein extraction followed the procedure of Batista de Souza et al.12 and Omonhinmin et al.16

Data analysis

Mean values were estimated using Excel (2013) and subjected to descriptive statistics and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Paleontological statistical software (PAST). The trial design of randomized factorial scheme of 12+1+3 as described by Oresegun et al.14 Significant differences were set at an alpha level of 5%. Monomorphic and polymorphic protein bands were recorded for each variety based on staining intensity. Protein bands were scored as discrete values 0 (absent) and 1 (present) and used to generate algorithm and then subjected to PAST and produced a dendrogram. The standard proteins with their molecular weights used are hen egg-white lysozyme (15KDa), chymotrypsinogenA (25KDa), ovalbumin (45KDa) and bovine serum albumin (67KDa).

Proximate evaluation

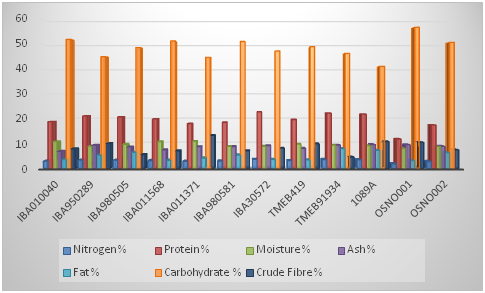

Data in Table 2 shows the proximate parameters in percentages evaluated for the 12 varieties of cassava studied. Variety IBA30572 yielded higher crude protein (CP) percentage with a mean value of 22.75±0.06 while OsNo01 recorded lower CP concentration with a mean of 11.81±0.06 and significantly different (P<0.01). Mean values of moisture content (g 100g-1) were higher in varieties IBA011371 (10.90±0.04), IBA011568 (10.82±0.03) while OsNo001 recorded lower value of 8.09±0.02. Varieties 1089A yielded the highest ash value of 9.64±0.08 while IBA010040 yielded the lowest value of 6.88±0.42. There was no significant difference (P<0.01) in the mean values of ash content of varieties IBA011568 and IBA011371, respectively. Similar trends were recorded between varieties IBA950289 and TMEB91934 with ash content values of 9.37±0.31 and 9.37±0.24 while other varieties differs significantly (P<0.01). The percentage fat content ranged from 3.16±0.05 in OsNo001 to 8.00±0.02. There was significant difference among the percentage fat content among the 12 varieties of cassava used in this study. The percentage carbohydrates were also significantly different with variety OsNo001 yielded the highest carbohydrate of 56.85±0.02 while variety 1089A yielded the lowest value of 41.13±0.04. The percentage crude fibre was highest in 1089A (10.84±0.07) while TMEB91934 recorded the lowest value of 4.57±0.06. Figure 1 shows the comparison of the percentage Nitrogen, Protein, Moisture, Ash, Fat, Carbohydrate and Crude fibre the 12 varieties of cassava leaves studied.

Variety |

Protein (%) |

Moisture (%) |

Ash (%) |

Fat (%) |

Carbohydrate (%) |

Crude Fiber (%) |

IBA010040 |

18.81±0.39d |

10.77±0.07f |

6.88±0.42a |

3.61±0.32d |

52.00±0.04j |

7.94±0.21e |

IBA950289 |

21.19±0.52g |

8.97±0.25c |

9.37±0.31ef |

5.39±0.05f |

45.05±0.01c |

10.04±0.12f |

IBA980505 |

20.78±0.02f |

9.73±0.20e |

8.68±0.03d |

6.50±0.01g |

48.71±0.11f |

5.60±0.13b |

IBA011568 |

19.94±0.07e |

10.82±0.03f |

7.47±0.8b |

3.32±0.20b |

51.33±0.20i |

7.14±0.03c |

IBA011371 |

18.03±0.05c |

10.90±0.04f |

8.78±0.06d |

4.19±0.21e |

44.79±0.40b |

13.33±0.31i |

IBA980581 |

18.60±0.06d |

8.89±0.05b |

8.82±0.07d |

5.43±0.04f |

51.15±0.01i |

7.13±0.23c |

IBA30572 |

22.75±0.06j |

8.95±0.06b |

9.19±0.29e |

3.63±0.31d |

47.31±0.03e |

8.16±0.10e |

TMEB419 |

19.69±0.04e |

9.78±0.01e |

8.13±0.23c |

3.45±0.05c |

49.03±0.02g |

9.93±0.05f |

TMEB91934 |

22.31±0.05i |

9.37±0.03d |

9.37±0.24ef |

8.00±0.02i |

46.37±0.03d |

4.57±0.06a |

1089A |

21.88±0.01h |

9.17±0.05d |

9.64±0.08g |

7.34±0.03j |

41.13±0.04a |

10.84±0.07h |

OsNo001 |

11.81±0.06a |

8.09±0.02a |

9.59±0.06fg |

3.16±0.05a |

56.85±0.02k |

10.50±0.04g |

OsNo002 |

17.50±0.04b |

8.89±0.02b |

8.90±0.07d |

6.44±0.06g |

50.75±0.09h |

7.52±0.12d |

Table 2 Proximate composition of the 12 cassava varieties evaluated

Note: Values in the same column with different superscript show significant differences (P < 0.01). Higher values in bold.

Figure 1 The comparison of the percentage Nitrogen, Protein, Moisture, Carbohydrate, Ash, Crude fibre and Fat of the 12 varieties of cassava leaves studied.

SDS-PAGE leaf protein profiling

The SDS-PAGE analysis of the 12 varieties of cassava showed bands of molecular weights ranged from 14kDa to 100kDa. A total of 58 bands were detected ranged from 0 to 6 as shown in Table 3. Protein bands of 14-23kDa, 24-32kDa and 33-44kDa generated a total of 11 bands each representing 18.97% of the total bands. The 45-65kDa generated 25 bands (43.10%) while 66-100kDa was monomorphic (20.69%). The protein of 14kDa is covalently coupled to yellow dye while 25kDa, 30 kDa, 40 kDa, 70kDa and 100kDa are covalently coupled to blue dye.

Well lane |

Protein group by molecular weight (kDa) |

||||||

Samples |

14-23 |

24-32 |

33-44 |

45-65 |

66-100 |

Number of bands |

|

1 |

IBA010040 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

2 |

IBA950289 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

IBA980505 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

4 |

IBA011568 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

IBA011371 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

6 |

IBA980581 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

7 |

IBA30572 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

8 |

TMEB419 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

9 |

TMEB91934 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

10 |

1089A |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

OsNo001 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

12 |

OsNo002 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

Total |

11 |

11 |

11 |

25 |

Mono |

58 |

|

% |

|

18.97% |

18.97% |

18.97% |

43.10% |

20.69% |

|

Table 3 Characterization of five protein bands generated from the 12 varieties of cassava leaves studied

Mono, Monomorphic

Cluster analysis

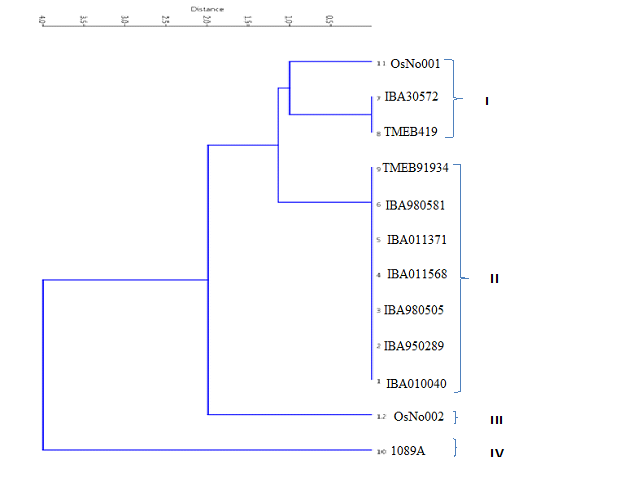

The cluster analysis based on Euclidean distance resulted into four (4) major cluster groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Cluster analysis of the leaf protein profiling of the 12 cassava varieties based on SDS-PAGE.

Cluster I: made up of 3 varieties (OsNo001, IBA30572 and TMEB419)

Cluster II: consisted of 7 varieties (7 varieties (TMEB91934, IBA980581, IBA01137, IBA011568, IBA980505, IBA950289 and IBA010040)

Cluster III: OsNo002

Cluster IV: 1098A.

The proximate and SDS-PAGE of leaf protein of twelve cassava varieties were investigated. The study clearly validates a considerable variation in protein, moisture, ash, fat, carbohydrates and crude fiber of the varieties as had been previously reported.14,17 Thus, with respect to the proximate analysis and protein profile of the cassava varieties studied, the leaves can nutritionally serve as leafy vegetable when properly cooked and processed. Though phytochemicals such as flavonoids, alkaloids and tannins were not available in the varieties of cassava used for this study, such phytochemicals have been reported by previous studies.4,5,18 The protein contents are also comparable to earlier reports on cassava leaves.2 The range of the protein content (11-22.88%) is highly comparable to that of Amanranthus (19.6%). The range obtained from this study also compares favorably with the range of percentage protein level in green vegetables, though a higher range of 16.7 to 39.9% have been reported.2,19 Accordingly, the proximate evaluation of the protein, moisture, ash, fat, carbohydrate and crude fibre contents examined aligned with similar studies on proximate analysis of cassava.1,2,4 It is remarkable to note that the accessions generated different values in proximate analysis which can be linked differences in genetic constitution of the varieties, sources of planting materials, maturity stage, climate change and possibly soil fertility. Generally, variety IBA30572 was found to record higher value of protein and nitrogen percentages and invariably could be a variety to be considered as potential leafy vegetable as well as source of cassava leaf and peel as animal feed. Various proximate parameters also signposts a rich content in nutrients and thus as a supplement leafy vegetable by man and ruminant animals as well. The nutritional and health benefits of consuming edible vegetable as component of human diet have been highlighted.1,2,20

The result of SDS-PAGE indicates the presence of proteins in all the samples of cassava leaves analyzed thus supporting the presence of crude proteins which can be nutritionally explored. The reproducible storage proteins with molecular weights of range 14kDa to 160kDa were observed. The protein of 50kDa, 120kDa and 160kDa covalently coupled to orange dye, protein of 25kDa, 30kDa, 40kDa, 70kDa and 100kDa covalently coupled to blue dye while those of lower molecular weight like protein of 14kDa covalently coupled to yellow dye. The band analysis of the protein profiling generated a considerable level of polymorphisms which also aligns with the diversity in the proximate evaluation of the varieties studied. The cluster analysis from the SDS-PAGE resulted into four major cluster groups suggesting the presence of four types of protein: bovine serum albumin, ovalbumin, chrymotrypsinogen and lysozyme. Though, these may probably represent low quality protein with similar amino acid content, the proteins could serve important nutritional function to aid digestion and growth in living cells. The presence of these proteins, however, indicates protein diversity which could be further explored among the cassava varieties for maximum utilization. Though a large quantity of carbohydrates are available in cassava, more scientific evidences are required to establish the quantity and various types of protein available in cassava. The varieties used for this study are a mixture of breeding lines and landraces from farmer which are characterized by differences in protein, moisture content, ash, and crude fiber and therefore could be utilized in product development and use as leafy vegetable. The use of cassava leaves and peels as components of animal feeds is gaining research and commercial attention which can possibly offers a better diversification options for the crop. Findings from this attempt has provided insight into utilization alternative of cassava as leafy vegetable that can be adopted and also incorporate into feeding concentrates for animals.

This study demonstrates that proximate components of protein, moisture, crude fibre, carbohydrates, ash and fat of the cassava varieties compared favorably with other green vegetables. It is also evident that the protein content might be sufficient enough to adopt cassava leaves as a leafy vegetable based on the SDS-PAGE analysis. However, further toxicity studies on the leaves and leaf processing for consumption will enhance the adoption of cassava leaves as a leafy vegetable.

Sample collection was funded from a research grant (No. CUCRID RG 022.01.15/FS) awarded on Cassava for Food Security Project by Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Discovery.

We acknowledge the support of Covenant University for providing the enabling environment, the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture and farmers for release of Cassava accessions used for this study.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Popoola, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.