MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2919

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 5

Department of Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences, Taraba State University, Jalingo, Nigeria

Correspondence: Peter Joseph, Department of Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences, Taraba State University, Jalingo, Nigeria, Tel 07084087066

Received: September 26, 2022 | Published: October 28, 2022

Citation: Abdullahi I, Mogbolukor JA, Peter J, et al. Classification of private hospitals in Northern Senatorial District of Taraba State, Nigeria. MOJ Eco Environ Sci. 2022;7(5):142-152. DOI: 10.15406/mojes.2022.07.00260

The study determined the spatial distribution and classification of private hospitals in the Northern Senatorial District of Taraba, Nigeria. A survey research design was adopted for the study. Interview, ground truth observation and handheld GPS device were the tools employed in data collection. Data analysis involved the descriptive statistics and geospatial mapping of the study area. The result shows that there are 40 private hospitals across the northern senatorial districts of Taraba state. These are distributed as follows; Karim-Lamido has seven (7), Ardo-Kola has three (3), Lau has three (3), Yorro has three (3), Zing has one (1), and Jalingo has twenty-three (23). The result shows that the nearest neighbour ratio is 0.816940 (observed mean distance divided by the expected mean distance), with a critical value of <-2.58 and a test of significance of P-value of 0.0071445. The result shows that the spatial pattern of distribution of private hospitals in the northern Taraba senatorial district is random, and there is less than 1% likelihood that this random pattern could be the result of random chance. The random pattern shows that the hospitals are not evenly distributed over space. This implies that the private hospitals in the northern senatorial district of Taraba State are randomly distributed. The result shows that there are 94 medical doctors and 176 nurses representing 27.9% and 52.2%, respectively, showing an average ratio of one doctor to two nurses per hospital (1:2). The result revealed that two (2) private hospitals are single-specialty tertiary care hospitals; Nobis Eye Clinic offering ophthalmological care services while Balsam Clinic offers osteology services. Three (3) general secondary care services (Jaji Memorial Hospital, UMCN Hospital & Catholic Hospital), while the remaining thirty-five offer primary care/nursing homes. The result also shows that there are three (3) specialty hospitals in the study area; this includes osteology (Balsam Clinic), ophthalmology (Nobis Eye Clinic) and a dental hospital (Family Dental Hospital). All these are located in Jalingo, the state capital. The others offer services in the category of general hospitals, though only a few (3) have the bed capacity to be classified as a general hospital. The study recommended that the distribution of private hospitals should be planned in such a way that they can reach more patients in terms of spatial coverage. It is further recommended that private hospitals should upgrade their facilities and bed capacity and employ more nurses and pharmacists to cater for the vast number of patients in the study area.

Keywords: private hospitals, classification, GPS, GIS, Northern Taraba, Nigeria

Hospitals' particular responsibilities vary by country and are usually dictated by legal restrictions. In certain countries, healthcare facilities must also meet a minimum size requirement (such as the number of beds and medical staff required to provide 24-hour access) in order to be classified as a hospital.1 For example, a hospital must "keep at least six in-patient beds, which shall be continually available for the care of patients... who stay on average in excess of 24 hours per admission" in order to register with the American Hospital Association. Other requirements include continuous supervision by nurses, pharmacy services, food service, and medical records.2

Hospitals can be categorised according to their functional level of care (primary, secondary, tertiary), administrative level of ownership (national, regional/city, district and local), size (number of beds), type of ownership (public or private), and a range of specialties (general health care or a single specialty). Differences in case-mix and technical capacity differentiate hospital categories, but service range and levels of care can vary dramatically as well. Typically, to be categorised as a hospital, facilities need to have at least ten beds.

According to Ademiluyi and Aluko-Arowolo3 health care is divided or classified according to levels of services rendered, specialities, number of specialists and in-patient beds. In Nigeria, there are three health structures that are classed and organised in a hierarchical fashion. There are three types of health institutions: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary health care facilities are unquestionably the first port of contact for sick and injured people. They handle minor medical issues such as malaria, fever, colds, and nutrition disorders, among others. They are primarily used for minor health issues and health education. They also deal with infants, mothers, and pregnancies. Family planning and immunisation are two other health considerations in their care.4 Finally, primary health centres emphasize health care and are involved in record-keeping, case reporting and patient referral to higher tiers. Primary health centres are known within the system by the content of health centres, maternity homes/clinics and dispensaries. Primary health facilities, according to the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN) in Badru,4 also provide health education, diagnosis, and treatment of common ailments using adequate equipment, infrastructure, and an essential medicine list.

Complicated cases are referred to secondary general hospitals from primary healthcare institutions. Secondary health centres are responsible for not just prevention but also treatment and management of difficult minor cases. The more difficult patients, on the other hand, are referred to a tertiary or specialist hospital. Comprehensive health facilities and ordinary hospitals are examples of secondary categories. The comprehensive health centres are often owned by private individuals(s) or a group of individuals, e.g. Courage Hospital, Jalingo, Victory Hospital, Ijebu-Igbo, Gateway Hospital, Jalingo, etc., while general hospitals are owned and funded by the government. Examples are general hospitals in Wukari, Bali, Gembu, Zing, etc.

Ademiluyi and Aluko-Arowolo3 stated that General Hospitals have provisions for accident and emergency units and diagnosis units (including X-ray, scan machines and other pathological services), among other services. As a second-tier health facility, it is required to meet specific requirements and maintain a particular degree of infrastructure. According to the Nigerian Medical and Dental Council, any general hospital should have at least three doctors who can provide medical, surgical, pediatric, and obstetric care.3 Furthermore, the general hospital incorporates the facilities of primary healthcare into its own to play its role as a second-tier health institution. As a matter of fact, to be so qualified, it should provide simple surgical services, supported by beds and bedding for a minimum of 30 patients. There should also be ancillary facilities for proper diagnosis and treatment of common ailments. General hospitals are often within the control of state governments and private individuals or groups of individuals.

A tertiary health institution also called a specialist/teaching hospital, handles complex health problems/cases either as referrals from general hospitals or on direct admission to its own. It has such features as accident and emergency unit, diagnostic unit, wards units, treatment unit and out-patient consultation unit. All these units are to be equipped with the necessary facilities and staffed by skilled personnel. Teaching hospitals also conduct researches and provide outcomes to the government as a way of influencing health policies. This explains why this type of health institution is often university-based.3 The classification of private hospitals will go a long way in documenting the range of medical services rendered and specialties available in such facilities.

Hospitals come in a variety of shapes and sizes to meet the diverse needs of society. Their structure, purpose, and performance are all distinct. This difference is due to their unique nature and form. Hospital classification aids managers and owners in better managing their facilities, as each type of hospital has a variety of specialties.2

Many people in the world today depend on hospital most especially the private hospital, because it provides the needed attention to them. Patients generally prefer private hospitals because of the many amenities available and the better doctor-to-patient ratio. A private hospital is generally owned by an individual doctor or a group of doctors. They accept patients who are suffering from, e.g. infirmity, advanced age, illness, injury, chronic disability, etc. or those who are convalescing. And mostly not admit patients who are suffering from communicable diseases, drug-addition or mental illness. They offer a range of services similar to the found in a hospital and are run on a commercial basis.

Naturally, the ordinary citizens in Nigeria and Taraba State usually cannot afford to get medical treatment in private hospitals. However, private hospitals are becoming more and more popular due to the shortage of funding of government and voluntary hospitals. Wealthy patients do not want to get treatment or receive treatment at public hospitals due to long queues of patients and shortage of medical as well as staff leading to a lack of better medical care. Classification of private hospitals would provide a guide to the specialties in such hospitals and the range of services available as well as the number of personnel and the capacity of the hospital in terms of population coverage.

There is no appropriate identification and classification of private hospitals within the study area, which often leads to the admission of patients in the wrong hospital that does not offer the needed service for a particular ailment. This may result in complications or delays in getting the needed expert medical services. It's against this background that this study seeks to examine the classification of private hospitals in Taraba State, a case study northern senatorial zone. With the aim of classifying them based on how they operate and deliver services to the populace within the study area of the northern senatorial zone of Taraba State in the north east of Nigeria.

To achieve the stated aim, the objectives of the study are to; identify and take inventory of the private hospitals within the study area; identify the kind of facilities and personnel available in the private hospitals, and attempt the classification of private hospitals within the study area based on their size, facilities and personnel.

Concept of classification

Most countries strive to arrange their healthcare systems in such a way that people, families, and communities get the most out of the latest knowledge and technology available for the promotion, maintenance, and restoration of health. Governments and other agencies are tasked with a variety of activities in order to contribute to this process, including the following5,6:

Others include special services for certain populations (such as children or pregnant women) and specialised requirements (such as nutrition or immunisation); preventative services, which protect people's and communities' health; health education; and, as previously indicated, data gathering and analysis.5,7

There are several types of medical practice in the curative realm. They can be thought of as forming a pyramidal structure, with three layers indicating increasing degrees of expertise and technical sophistication while serving fewer patients as they are filtered out of the system at lower levels. Only patients who require extra care, either for diagnosis or treatment, should progress to the second (advisory) or third (specialist treatment) tiers, where the cost per service item rises. The first level is primary health care, often known as first contact care when patients make their first interaction with the healthcare system.5,7

Primary health care is an essential component of a country's healthcare system, and it is the largest and most significant component. According to the World Health Organization, "primary health care should be based on practical, scientifically sound, and socially acceptable methods and technology" made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation at a cost the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in line with the Ata Declaration.5,7,8 Primary health care is normally administered by a medically qualified physician in industrialised countries; but, in underdeveloped countries, first-contact treatment is sometimes provided by non-medically qualified workers.

At the primary level, the vast majority of patients may be fully treated. Those who cannot are directed to the second tier (secondary health care or referral services) for a second opinion or X-ray examinations and another testing from a doctor with specialised skills. Secondary health care frequently necessitates the use of technologies available at a local or regional hospital. However, radiographic and laboratory capabilities offered by hospitals are becoming available directly to family doctors, boosting their service to patients and broadening their scope.6

According to Uchendu et al.,7 institutions such as teaching hospitals and units dedicated to the treatment of specific groups—women, children, patients with mental problems, and so on—provide the third tier of health care, which employs specialised services. The dramatic differences in treatment costs at various levels are especially important in developing countries, where the cost of treatment for patients at the primary healthcare level is usually only a small fraction of that at the third level; medical costs at any level, however, are usually borne by the government in such countries.6

In an ideal world, Lal 5 noted that all patients would have access to health care at all levels; this would be considered universal health care. The wealthy, both in relatively prosperous industrialised countries and in impoverished developing ones, may be able to obtain medical care from private sources they desire and can afford. The vast majority of people in most nations, on the other hand, rely on government-provided health services in various ways, to which they may contribute a small amount or nothing at all in the case of poor countries.6

Non-medically qualified professionals provide primary health care, or first-contact care, in many parts of the world, notably in developing nations; these cadres of medical auxiliaries are being trained in increasing numbers to fulfill overwhelming requirements among rapidly growing populations. Even among the world's comparably wealthy countries, which account for a significantly smaller fraction of the global population, rising healthcare expenses and the cost of training a physician have prompted some reconsideration of the role of the medical doctor in providing first-contact care.5,7,8

Borishade9 averred that a patient's direct access to a specialist is an obvious alternative to general practice. If a patient has vision problems, he sees an eye specialist, and if he has chest pain (which he thinks is caused by his heart), he sees a heart specialist. One criticism of this strategy is that the patient often has no idea which organ is causing his symptoms, and even the most thorough physician may be stumped after conducting numerous tests. Breathlessness is a typical sign of heart illness, lung disease, anaemia, and emotional distress. Another typical symptom is a general malaise, which includes feeling weary all of the time; other symptoms include headaches, chronic low back pain, rheumatism, abdominal pain, poor appetite, and constipation.9

Some people may show signs of anxiety or depression. The ability to examine persons with such symptoms and discriminate between symptoms that are mostly caused by emotional distress and those that are primarily caused by bodily distress is one of the most subtle medical talents.6 A specialist may be capable of such a broad assessment, but he frequently fails at this point due to his focus on his own field.

According to Borishade9 Nigeria's healthcare system follows the universal three-tiered system of primary, secondary, and tertiary care. Each level of the public administration system is overseen by the federal, state, and lowest governing authorities (LGAs), which are analogous to municipalities. In Nigeria, the LGAs are in charge of primary healthcare. The authorities are the country's lowest level of government, analogous to towns and regions in other countries. The LGAs are responsible for providing healthcare to the population at the most basic levels and institutions, including primary health care and child vaccination centres, as well as local and community health clinics, in addition to providing and maintaining basic primary education and basic infrastructure.7,9

Institutions such as state general hospitals and private specialty hospitals provide secondary healthcare services. This level of healthcare delivers services that are superior to those provided by primary healthcare facilities.7 The state government (i.e., the state ministry of health) provides healthcare at this level, which essentially provides specialist treatments to patients referred from primary care through out-patient and in-patient services for general medical, surgical, and community health requirements. Laboratories, diagnostics, and blood banks are available as support services.7,9,10

According to Uchendu et al.,7 tertiary healthcare services are those that are offered by highly specialised institutions and are thus the highest degree of healthcare available in the country. This level of care offers highly specialised treatments in a variety of fields, including orthopaedics, psychiatry, maternity, and paediatrics.5,8 University teaching hospitals, federal medical centres, and other national specialist hospitals are among the institutions at this level. In Nigeria, public healthcare facilities at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels are scarce and politically unequally allocated. They severely lack infrastructure and manpower, particularly at the local government level and in rural areas 10. The private sector fills the void in primary healthcare and has the greatest impact, using both sophisticated western and traditional hospitals and clinics.

In the public healthcare service system, Asrani8 noted that patients require a referral to see a specialist except in a case of emergency. Both public out-patient and in-patient secondary care are provided by hospital districts. Referral hospital services necessitate a trained workforce to accomplish their goals. Attempting to build referral hospitals on a wide scale will clearly be impossible if specialised staff are not available in a country. Many countries, on the other hand, may have an excess of specialised personnel and a scarcity of well-trained generalists. Where there are a large number of experts, resources will be drawn disproportionately to the referral level and away from district health systems. Positive reforms will necessitate a substantial training or retraining strategy wherever such inequalities occur.5,7,8

Relationship between Service Quality and the Private Healthcare Sector

Nursing, customer service, food and beverage, laboratory services, pharmaceutical services, information technology, doctors, and hospital administration are just a few of the departments that can deliver high-quality service in a hospital setting. These departments are equally crucial in providing high-quality medical care and, as a result, ensuring patient satisfaction.11

The following are some of the reasons why a healthcare facility's service quality should be improved:

Improved service quality in the private healthcare sector, according to health experts, is the proper thing to do12

Customer involvement and satisfaction have an impact on behaviour12 as the service quality of the provider improves, the expectations of the customer increase. Lee13 explained that as customers become more quality conscious, requirements for higher quality service increase.

Several studies have shown that there is an important connection between service quality and customer satisfaction and retention,14 loyalty,15 costs,16 profitability,17 service guarantees18 and financial performances.19 Additionally, these researchers have emphasised the significance of understanding, measuring and improving the quality of service provided by a private hospital.

Healthcare services

Healthcare is that service that is responsible for looking after the health of all the people in a country.20 The services of health care stand for the value of natural life amenities which qualifies a patient to live in the fullness and to function best.21 Real and well-organised healthcare services enable the individuals to get a complete, effective and self-controlled emotion, mind and body functioning harmoniously with combined psychometric items.22

The healthcare sector is designed to improve the physical and mental well-being of all people by preventing, diagnosing, and treating illness and by supporting optimal function.22 Across the lifespan, healthcare helps individuals live healthily, recuperate from sickness, stay with chronic sickness or infirmity, and survive with death and dying. Quality healthcare provides these services in ways that are timely, patient-centred, safe, equitable, and efficient. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the year 2001 dispensed a revolutionary report "—Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century—" which beckoned on countries to assertively tackle the intense defects in the provision of quality healthcare. The Institute of Medicine defined healthcare quality as "effective, timely, safe, patient-centred, equitable and efficient. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the federal government's leading agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency and effectiveness of health care, defined healthcare quality as performing the correct thing for the right customer (patient), at the appropriate time, in the appropriate way to attain the greatest imaginable outcomes. These two definitions offer us a perfect image of suitable healthcare quality. Health care services are centred on scientific and health confirmation and appropriate the exact information of an individual's life into deliberation, and the basic intention is to improve the quality of the health and life of the person receiving treatment.

The fundamental nature of healthcare was validated by Patricia23 in asserting that healthcare will not be successful except the healthcare service provider have the adequate competencies to carry out the services professionally and to evaluate their effectiveness.

The healthcare service quality

There has been a whole lot of research on the assessment of healthcare service quality over the years. In contrast, to the quality of tangible products, healthcare service quality is really difficult to describe.9 Donabedian24 noted that as we look forward to explaining quality, we in a little while become knowledgeable of the fact that numerous originations are equally possible and genuine.25 Despite the fact that there exist numerous explanations on the healthcare service quality in different studies, the notion remains complex and unclear.26 Martinez-Fuentes27 asserted that the healthcare service quality is a notion with several dimensions which reveals an assessment on whether the services rendered to the patients were suitable and perhaps the interaction between the patient and the doctor was appropriate. Scholars have diverse views on the different dimensions of healthcare service quality. According to Parasuraman et al.,28 the components of the healthcare service quality can be seen from five distinct dimensions, which include reliability, responsiveness, tangibles, empathy and assurance. Other scholars such as Levesque, Harris and Russell 6 have argued that the ability to pay for and ease of access to health care are significant dimensions of health care service quality. Nevertheless, a majority of the scholars categorise the components of health care service quality into diverse dimensions, which are centred on their personal experience and view on this subject matter. Generally, scholars have described healthcare service quality as the technical quality and relational treatment of service.29,30 As a result, healthcare service quality is categorised in terms of technical value and patient value. In the healthcare service sector, the technical aspect signified a medical or specialised value, whereas the patient value is a relational treatment quality.

According to the Institute of Medicine22 healthcare quality as a technical quality is the extent to which healthcare services for persons and the populace boost the possibility of anticipated health results and are dependable with present specialised understanding. This definition is acceptable among health care service scholars.31 Brook and Appel32 also defined technical quality as–the capacity of hospitals to accomplish extraordinary standards of customer/patient well-being via the medical diagnosis, processes and treatment, and eventually generating tangible or physical effects on customers or patients. It is, basically, what the patient obtains from the health care service workers and how healthy the diagnostic and healing procedures are useful. Otherwise stated, the technical aspect consists of the proficiency and medical expertise of the nurses and doctors and the laboratory specialists' skills in carrying out the test.33 In addition, Donabedian24 conceptualised three ways of describing the health care service quality as structure, process, and outcome, which comprise both technical quality and patient quality.

The structure is concerned with the measurement of the quality of healthcare location, which includes the design, organisation and techniques.34 There are basically two types of structures identified: physical and human features. The physical features comprise capital resources, for instance, buildings, equipment and personnel, the establishment of resources and controlling. At the same time, the staff features comprise the teamwork and staff skill mix, for example, the experience of the doctor, certification and their education.34 In general, the structure is not an end in itself; rather, it is a means to an end: high-quality health care; this means that the structure is normally not the central emphasis of research in healthcare quality.35 The process stands for organising medical training measures, which ensure standard processes endorsed for patient's circumstances. The process is the real service provision of treatment or care, which is also divided into two different dimensions: technical and relational care.24,25,36 Technical care means the use of the medical drug for a patient's health condition and is centred on the theory that has been used and tested over time for effectiveness and eventually recognised as a standard for treatment.24,34

Relational care is the interpersonal connection between the Structure Process Outcome of the healthcare service provider and the patient.37 However, the value of relational care in the measure of service quality is assumed to be less important in status in the health care arena.37 The outcome is the measurement of the health condition of the patients in addition to the assessment of the treatment of the patient. Although the measurement of the patient's health condition is, to a certain extent, objective when compared to patient assessment, it is challenging to assess just after a single service and experience of treatment are accomplished. An experience can comprise hospital care or post-acute treatment. The structural measure and the procedures of treatment have an impact on the outcome of treatment. For instance, the health condition of patients that have breast cancer may lead to death if the diagnostic experiment (structure) is inaccessible or the result of the test is misinterpreted (process).34

In the health care sector, the evaluation of the health care service quality was before now mainly centred on the result of health care service. Nevertheless, lately, the assessment of the procedures of healthcare has been carried out as the technical quality of health service but not of relational care. However, several scholars have stated the significance of considering the evaluation of the relational care from the patient standpoint because refining the patient, health care quality of the organisation is a determining feature in refining the total quality of health care.38 Ideally, the definition of quality from the angle of the patient perceives service quality and is described as the patient appraisal of the quality of total health services in all dimensions of service such as functional, technical, administrative and environmental, centred on the perceptions of what is obtained and what is granted.39

Study area

Location and Size: In terms of landmass, Taraba state is Nigeria's second-largest. It is situated in the southern section of north-eastern Nigeria, along the Nigerian-Cameroonian borderland. The state lies roughly between latitude 6°25’N and 9°30’N and between longitude 9°30’E and 11°45'. It is bordered on the west by Nassarawa and Plateau states, to the north by Bauchi and Gombe states and by Adamawa state to the northeast. It also shares its southwestern boundary with Benue state (Figure 1). Taraba state is bounded on the south and south-east by the Republic of Cameroon (an international boundary). The state has a total land area of 60,291km2.

Taraba state is made up of 16 Local government areas (LGAs) and three senatorial districts (northern Taraba, Southern Taraba, and Taraba central). Northern Taraba (the study area) consists of six LGAs, Ardo Kola, Karim Lamido, Lau, Jalingo, Yorro and Zing. The area has a tropical continental type of climate with wet summer and dry winter. Rainfall usually starts around May/June and ends in about September/ October. The area receives an average rainfall of about 900mm per annum. The mean maximum temperature of the area is about 30°C. The highest air temperature is normally experienced in March and April. Maximum temperature ranges between 26°C to 39°C, while minimum temperature ranges between 15°C to 18°C.40

Method: A survey research design was used in this study. The survey design is appropriate because it is concerned with conditions that exist, practices that are prevailing, perception of individuals and processes that were going on.41 The source of data includes primary and secondary sources. The primary data source was specifically through three instruments; in-depth interview, participant observation and the collection of the coordinates of the private hospitals using the hand-held Global Position System (GPS). This involved taking and recording the coordinates of each of the private hospitals in northern Taraba. An in-depth interview of the key personnel in each of the hospitals was carried out to get in-depth knowledge of the staff strength and bed/patient capacity. The secondary data in this study included: published and unpublished materials, journals, magazines, the internet, and an administrative boundary map of the study area.

A census sampling technique was used in identifying the private hospitals in the study area. A census sampling is a sampling technique that attempts to gather information about every individual in a population. A census is a gathering of data from all units of a population, often known as a “full enumeration.” When we need precise data for a large number of subgroups of the population, we employ a census. A census is frequently the best answer for such a survey because it requires a big sample size.

Interview, ground truth observation and GPS device were used as means of data collection. The interview questions were structured to cover the principal medical officer of each facility and any other medical support staff, preferably a nurse. Research assistants were recruited and trained on the objectives of the study as well as the procedure for the collection of facility information and GPS coordinates. This is to ensure complete coverage of all the private hospitals within the study area.

Data generated from this research were analyzed by using inferential statistics involving the use of mean, frequencies and percentages using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23.0. The data for the spatial distribution of infrastructural facilities in the study, which are coordinates of the various facilities, were inputted into the ArcGIS environment, and the map of the study area was extrapolated to show the spatial distribution of the selected public facilities in the study area.

To create a visual map of points and polygon feature classes, the database vector shapefiles were imported into the ArcGIS environment. On the map, the geographical location and distribution of private hospitals across the study area are shown.

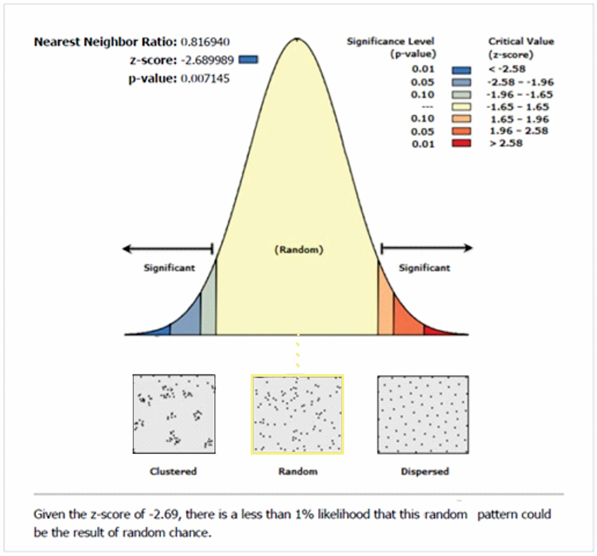

The spatial statistical tool in ArcGIS 10.1, Nearest Neighbor Analysis (NNA), was used to compute and determine the spatial pattern that exists between hospitals in the study area. Nearest Neighbor Analysis compares the mean distance (Do) of the phenomena in issue to the same expected mean distance (De), usually under a random distribution, to uncover patterns in location data. The analysis usually produces the Nearest Neighbor Ratio (Rn) result between 0–2.15. If the Rn value result falls between a range of 0-0.49, the pattern is said to be significantly clustered, while a range of 0.5–1.5 indicates a significant random distribution; if the Rn value falls within 1.56–2.15, the pattern is said to be significantly dispersed or regular depending upon the number of points per pattern. A Negative Z score indicates clustering, while a positive Z score means dispersion or evenness.42

Spatial distribution of private hospitals

Figure 2 shows the spatial location of private hospitals within the study area. The study revealed that there are a total of 41 private hospitals across the northern senatorial districts of the state distributed across the six local governments in the zone. Karim-Lamido has seven (7), Ardo-Kola has three (3), Lau has three (3), Yorro has four (4), Zing has one (1), and Jalingo has twenty-three (23). The result shows the presence of a private hospital in all the local governments in the study area, which indicates that alternative healthcare services are available and accessible to the general populace besides the public hospitals, primary health care centres and dispensaries in the study area.

Distribution pattern of private hospitals in Northern District of Taraba State

The distribution pattern of private hospitals in the northern Taraba senatorial district carried out with the aid of the average nearest neighbourhood analysis as shown in Figure 3 and Table 1. Table 1 indicates that the private hospitals in the northern Taraba senatorial district are randomly distributed. The result shows that the nearest neighbour ratio is 0.816940 (observed mean distance divided by the expected mean distance), with a critical value of <-2.58 and a test of significance: P-value of 0.0071445 as shown in Figure 3. The result of the breakdown shows that the spatial pattern of distribution of private hospitals in the northern Taraba senatorial district is random (Table 1), and there is less than a 1% likelihood that this random pattern could be the result of random chance. The random pattern shows that the hospitals are not evenly distributed over space. This implies that the private hospitals in the northern Taraba senatorial district are randomly distributed. This simply indicates that the sitting of private hospitals does not follow a particular pattern across the district. This could be attributed to the difference in landforms and population distribution. Most private facilities are profit-making ventures. Thus, they would be situated around densely populated areas where their services can be accessed by the general populace.

Figure 3 Average Nearest Neighbour Analysis of the Distribution of Private Hospitals in Northern District of Taraba State.

Observed Mean Distance |

895.786090 Meters |

Expected Mean Distance |

1096.514063 |

Nearest Neighbor Ratio |

0.81694 |

Z – Score |

-2.689989 |

P – score |

0.007145 |

Input Feature Class |

Masks Points |

Distance Method |

Euclidean |

Study Area |

283752969.3 |

Selected Set |

FALSE |

Table 1 Average nearest neighbor summary of private hospitals

Source: Authors Analysis 2022

Facilities and personnel in private hospitals

The distribution pattern of private hospitals in the northern Taraba senatorial district is presented in Table 2. The result presented in Table 2 shows the staff strength of private hospitals in the study area. From the result, there are 94 medical doctors and 176 nurses representing 27.9% and 52.2%, respectively.

Staff type |

Frequency |

Percentage |

Medical Staff |

||

Doctors |

94 |

27.9 |

Nurses |

176 |

52.2 |

Pharmacists |

26 |

7.7 |

Lab Technicians |

41 |

12.2 |

Total |

337 |

100 |

Non-Medical Staff |

||

Security |

56 |

31.6 |

Cleaners |

67 |

37.9 |

Admin |

54 |

30.5 |

Total |

177 |

100 |

Cumulative |

494 |

|

Table 2 Staff strength of private hospitals in Taraba Northern Senatorial District

Source: Field Survey, 2021

This shows that there is an average ratio of one doctor to two nurses per hospital (1:2). The result also shows that private hospitals in the study area have 26 pharmacists and 41 laboratory technicians, representing 7.7% and 12.2%, respectively.

The result of the interview revealed that most of the private hospitals often hire visiting doctors and rarely have consultants except for the specialty hospitals, which have specialists who are consultants and offer professional services in orthopaedic and ophthalmic care. Also, most of the nurses are student-nurses who are on attachment/ training. These groups augment the lack of staff available to service a large number of patients. Table 2 shows that for non-medical staff, there are 56 security, 67 cleaners and 54 administrative staff representing 31.6%, 37.9% and 30.5%, respectively.

Classification of private hospitals

This part provides a classification of private hospitals based on the type of services offered and based on the objective.

Classification of private hospitals based on level of services

Figure 4 shows a spatial distribution of private hospitals based on objectives. The result shows that the three private health facilities in Ardo-Kola meet the criteria for classification as primary care facilities. The low presence of private hospitals in this location, especially those that offer higher levels of care, could be attributed to the rurality of the area. Generally, it is believed that rural dwellers believe and patronize traditional care before visiting any hospital for treatment. This is affirmed by one of the proprietors of an orthopaedic hospital in Jalingo. The respondents said most patients only resort to hospitals for treatment often when the conditions are nearly irredeemable and can only be managed. This has resulted in many losing parts of their body and, in some cases, loss of lives. This exposes the failure of the Nigerian governments across all arms and tiers and the lack of priority given to the provision of basic health care. The presence of private hospitals in rural areas often complements the often nonfunctional and understaffed government healthcare facilities, which lack the capacity to adequately cater or the need of their communities.

The result in Figure 5 shows that there are twenty-three private hospitals in Jalingo Local Government Area. Among these, there are two (2) hospitals offering tertiary care services in ophthalmic and orthopaedic medicine; these single-specialty tertiary care hospitals are the Nobis Eye Center and Balsam Orthopedic Hospital. These hospitals offer professional and specialized medical services covering eye-related ailments and bone-related complications. The map also shows that there are four private hospitals providing a secondary level of care/services. These hospitals, based on their functional level, provide general outpatient medical services and general/specialized surgical procedures. These hospitals usually have the capacity to provide long-term treatment with equipped medical, general surgery and maternity. They usually have a resident medical staff. They are also capable of attending to and managing emergency cases. The remaining seventeen (17) private hospitals are classified as primary healthcare/dispensary and nursing home facilities because they only provide basic medical services without surgeries. Most of these facilities have in-patient bed capacities of less than 20.

Figure 6 shows the classification of private hospitals based on the levels of healthcare services rendered in Karim Lamido LGA. The figure reveals that all seven (7) private hospitals in the area offer primary care/dispensary services. This is true of most hospitals in rural areas as they are often concerned with basic medical services, which serve as intermediaries that provide immediate care for patients of common ailments and often non-surgical procedures. Those with complications are referred to higher hospitals, which are often government-owned. One of the nursing attendants in the private hospitals averred that there is often low patronage of patients, especially during the dry seasons. But the cases they usually attend to range from pregnancy/child delivery, malaria, and at times snake bites which is common during the rainy season and heat periods. This affirms the conclusion of Akande 43 that primary care clinics are the first point of contact for patients, who are then referred to the higher-level secondary and tertiary facilities depending on the level of treatment required.

Figure 7 shows that based on levels of care, there are two private hospitals offering primary care services in the Lau local government area of Taraba State. This, as is the case in most of the local government areas, are located in relatively developed towns and populated areas. These clinics/dispensaries/maternity homes provide a wide range of basic medical services, of which the major components are maternal and child care services.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the classification of private health care facilities in Yorro and Zing local government areas respectively. Yorro local government has four (4) private hospitals, while Zing has one. The high number of private hospitals in Yorro could be attributed to its proximity to Jalingo, the Taraba State capital. These hospitals fall within the level of primary care service providers. These primary care hospitals in Yorro are located around border communities between Yorro and Jalingo. They cater for the teeming population in that axis where advanced healthcare services cannot be accessed immediately by residents. The interview with staff revealed that they provide services mainly in maternal care and auxiliary medicine, especially with the fact that their medical directors are juxtaposed between their government employment and private practice. This, another nurse said, is responsible for the short term admission of patients in the private hospitals in the area.

Therefore, the classification of private hospitals based on level of services shows that two (2) private hospitals are single-specialty tertiary care hospitals; one offers ophthalmological care services while the other offers services in osteology. Four (4) general secondary care services, while the remaining thirty-five offer primary care/nursing homes. This means that there is a low distribution of specialty clinics/hospitals in the state as compared to primary care/nursing homes since most sicknesses among rural dwellers would need immediate care, which is often provided by these facilities. This finding reflects the conclusion of Akande43 that primary care clinics are the first point of contact for patients, who are then referred to the higher-level secondary and tertiary facilities depending on the level of treatment required.

Classification of private hospitals based on objectives

The result presented in this section shows the distribution of private hospitals based on objectives.

The result presented in Figure 10 shows the distribution of private hospitals based on objectives. The result revealed that the three (3) private hospitals in Ardo-Kola LGA are classified as general hospitals based on the class of services rendered, not necessarily because of their capacity to function as general hospitals. This is so because most of these hospitals do not have a large bed capacity and only offer services in general medicine and maternal/child healthcare.

Figure 11 shows the distribution of private hospitals in Jalingo based on their objectives. The map shows that there are twenty-one (21) general hospitals in the area. These, as indicated above, are generally concerned with basic general medical services. Because of their location and the population of patients patronizing these hospitals, they often provide a wider range of services compared to those in rural areas. They also have the advantage of reaching and serving more patients due to the population density in the urban areas and the search for medical care. The map also shows that there are two (2) specialty hospitals, which handle cases of Ophthalmological cases and orthopaedic services. These hospitals cater for the special needs of patients with eyes problems.

The result of the interview revealed that most of the patrons of these specialty hospitals are from rural areas across the state and neighbouring states. Most of them, as revealed by the medical director of the orthopaedic hospital, come to the hospital after attempting traditional care, and their conditions are already worse and often time the only option available is amputation. Public hospitals are always overstretched and under-funded, which drives down quality and lowers standards. Private hospitals, on the other hand, provide patients with a faster, more effective option, especially in the area of specialty services.

Figure 12 shows the distribution of private hospitals in Karim-Lamido based on objectives. The result revealed that there are seven (7) hospitals in Karim-Lamido; all these are classified as general service care hospitals. These hospitals provide a range of services generally required as a health facility. These basic healthcare services include general outpatient services and in-patient care.

Figures 13–15 show the distribution of private hospitals in Lau, Yorro and Zing local government areas respectively. The Figure 13 shows that Lau has three (3) hospitals, and Figure 14 shows that Yorro has four (4), while Figure 15 shows that Zing has one (1) private hospital. These group of hospitals are classified as general service hospitals. They only provide general outpatient medical services, which involve common ailments and diagnostic services that cover malaria, typhoid, radiology, microscopy and culture. They often lack the capacity to retain patients for the long term, given the high patronage of patients.

The result of the classification of private hospitals based on objectives of setting it up shows that there are three (3) specialty hospitals in the study area; this includes osteology, ophthalmology and a dental hospital. All these are located in Jalingo, the state capital. The others offer services in the category of general hospitals, though only four (4) have the bed capacity to be classified as a general hospital. This finding supports Nwakeze and Kandala44 conclusion that higher-level and private facilities are concentrated in state capitals or densely populated urban areas.

This study set out to examine the spatial distribution and classification of private Hospitals in the Northern Taraba senatorial district. The study had three objectives and three research questions. There are diverse hospitals serving the multifaceted needs of society. Many people depend on private hospitals because they provide the needed attention, and many offer amenities, better doctor-to-patient services. There is no appropriate identification and classification of private hospitals within the study area, which often leads to the admission of patients in the wrong hospital that does not offer the needed service for a particular ailment. This may result in complications or delays in getting the needed expert medical services.

The presence and proliferation of private health facilities show the need for health care services by the general populace. It also shows the desire of these facilities to provide these services and bring them closer to the people. There are 41 private hospitals across the northern senatorial district of Taraba state, with most of them concentrated in Jalingo, the state capital. The distribution pattern of the hospitals is random. There were 94 medical doctors and 176 nurses, showing an average ratio of one doctor to two nurses per hospital (1:2). There are two (2) single-specialty tertiary care hospitals; one ophthalmological care service and osteology services, three (3) general secondary care services, while the remaining thirty-five offer primary care/nursing homes. The result also shows that there are three (3) specialty hospitals in the study area; this includes osteology, ophthalmology and a dental hospital. All these are located in Jalingo, the state capital. The others offer services in the category of general hospitals, though only a few (3) have the bed capacity to be classified as a general hospital. This shows the majority of the private hospitals in Taraba northern senatorial district.

The distribution of these hospitals is impacting the ecology and environment of the region in diverse ways: Healthcare seekers will find it easy to access and know the nearness to medical and healthcare services they need, thereby reducing infant and maternal mortality as a result of timely access to medical facilities. The distribution of the hospitals in the region based on our classification serve as means of quick intervention by the government in terms of knowing the areas of need in modern medical facilities and human expertise needed in the area. The classification of the hospitals is also relevant for the integrated management of hospital waste as a means of promoting a sustainable environment. It serves as quick reference material for medical personnel who are maybe posted for an emergency operation to know what is available in the ecology of the new hospital being posted to and help in opening up the environment such that the residents of the environment know where to refer others to. Finally, it will help in better hospital, healthcare facilities and personnel management in Taraba State.

Recommendations

Based on the result and discussion, the study recommends the following:

None.

None.

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Abdullahi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.