MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2919

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 2

PhD in Education, Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil

Correspondence: Giseli Gomes Dalla Nora, PhD in Education, Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil

Received: February 22, 2025 | Published: March 11, 2025

Citation: Nora GGD, Tatibana MY. Application of the sustainability barometer in the municipality of Cuiabá – MT - Brazil (2010-2019). MOJ Eco Environ Sci. 2025;10(1):55-62. DOI: 10.15406/mojes.2025.10.00347

The excessive exploitation of natural resources, pollution and social inequality, among other factors, accentuated environmental problems and generated unsustainability in the environmental arena around the world. This global inflation in crisis led to emergence of in reflections on preservation of natural resources at a global scalel. Th is idea of sustainable development is being reviewed as one of the best proposed resolution to the global environmental crisis.

Therefore, this present work was undertaken with an aim to analyze the sustainability of the municipality of Cuiabá.

To accomplish the goals and objectives of ths work, the Sustainable??? Barometer methodology was applied in which a system of indicators was used, to verify the levels of sustainable development. The results led to the conclusion that, the municipality of Cuiabá has has serious urban problems.

Keywords: sustainability barometer, municipality of Cuiabá, sustainability

BS, sustainability barometer; IBGE, Brazilian Institute of geography and statistics; UNDP, United Nations development program; PNAD, National Household sample survey; IUCN, International Union of conservation of nature; IDRC, International development research centre; HDI, human development index; SNIS, National sanitation information system; Institute of applied economic research; MIS, mortality information system; LPS, local performance scale; SBS, sustainability barometer scale; STPs, sewage treatment plants

Today's society is characterized by technical-scientific and informational advances that give it unique characteristics never before imagined. On the other hand, it is a society of having rather than being, of frenetic speed, of fierce competition and marked by profound crises that objectively reflect the exhaustion of a productive process that, as it expands globally, reveals its perverse side through various forms of socio-environmental degradation.1 The overexploitation of natural resources, pollution and social inequality, among other factors, have accentuated environmental problems and generated environmental unsustainability that, ultimately, highlighted the environmental crisis, fueling the emergence of reflections on the preservation of natural resources worldwide (Brugger, 2004),2,3 since environmental risks are not limited to a specific time and space, that is, their effects can be felt with greater incidence over the years and reach several nation-states.4 They have also raised awareness that a healthy environment is closely linked to the preservation of the human species itself.4 Therefore, the problems created globally require integrated and joint solutions by those jointly responsible for business, industry and politics, as well as the sharing of responsibility between individuals and society.5

Faced with the threats of the environmental crisis, the concept of eco-developmentalism gained prominence in the 1970s, later replaced by sustainable development, without significant changes to the original conception.6 Because it is a concept that involves ideas of intergenerational pact and long-term perspective,7 and because it is an ecologically balanced development, which reconciles the development of the population with the preservation of environmental resources, in which the rational use of natural resources is necessary (Sirvinskas, 2005),2,3 Sustainable Development has become the most effective choice to face and overcome the crisis affecting the natural environment. This is because, according to Ferreira and Rosa,6 sustainable development

Thus, sustainability has become the backdrop for many debates and the driving force behind various social movements. However, more than changes in discourse, it requires real changes, which include changes in behavior, public policies and critical positioning.7 The State's contribution to achieving sustainable development is in the elaboration of integrative and participatory public policies. The implementation of such public policies does not indicate a block to economic development; on the contrary, it enables future generations to enjoy their right to a protected environment, guaranteeing them a dignified life (Scotto et al., 2007).2,3 In addition, there must also be interaction between the subjects involved in development in order to contribute to confronting the environmental crisis with a reflective and questioning vision, going beyond economic rationality and emerging in social, economic, political and ecological problems.2,3

Thus, this study aims to apply the Sustainability Barometer (BS) methodology in the city of Cuiabá. To this end, the system of indicators was used, which are useful tools for verifying levels of sustainable development and which assist in decision-making and the formulation of public policies.8 Research and data collection were carried out on official websites and archives of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD) and the City of Cuiabá.

Thus, the work is divided into 4 (four) sections. The first discusses the main concepts relevant to the theme; then the study area is presented; the third section describes the methodology applied, with the presentation of the sources and selection of indicators, and the application of the Sustainability Barometer. Finally, the fourth section addresses the analysis of the results together with the averages and classifications of each theme, as well as the presentation of the Two-Dimensional Graph with the averages of the Ecological Well-being and Human Well-being indexes.

Theoretical basis

Bsustainability arometer

When the topic is sustainability, one of the main challenges is its measurement, and one of the most recommended ways is the use of indicators.9 However, existing indicator systems present difficulties in interpreting the results obtained and lack sustainability parameters and goals to support comparison processes.9

One tool that overcomes some of these difficulties is the Sustainability Barometer. Developed in 1997 by experts from the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and with Robert Prescott-Allen as its main researcher and producer, the BS is a tool that combines a series of indicators related to the main dimensions: environmental well-being and human well-being, and the results are presented in an easy-to-interpret graphic format. Each of these two dimensions is subdivided into five others: land, air, water, species and use of resources for environmental well-being. Health and population, wealth, knowledge and culture, community and equity for human well-being.8

In this method, sustainability must be a combination of the two main dimensions, since a healthy society requires people and the ecosystem to be in balance (IUCN, 2003 at Prestes; Garcias; Lima, 2012). Cetrulo, Molina and Malheiros9 emphasize that the individual performance of the indicators that make up the dimensions does not allow an analysis of the situation as a whole, but, when combined, they demonstrate their results through aggregated indicators.

The performance scales are set up within a range of 0-100 and have five class subdivisions: Unsustainable, Potentially Unsustainable, Intermediate, Potentially Sustainable and Sustainable. The extremes of each class are defined according to the researchers' criteria and the real value of each indicator is transposed to this scale. Then, the averages for each dimension are found and subsequently expressed in a two-dimensional diagram. The division of the graph axes into five zones, as well as the scales of each indicator, prevents a good result on one of the axes from masking a bad result on the other axis.8

The graphical representation allows a view of the general picture of the state of the environment and society, facilitating the analysis of the interrelationship between both dimensions.8

The Sustainability Barometer

It stands out especially for its ease of use and clarity in the presentation of results. [...] It does not replace other conventional decision-making methods, but it can be used as an auxiliary technical tool for planners and managers, minimizing the probability of error in the decision-making process (Prestes; Garcias; Lima, 2012, p. 12).

Therefore, it was decided to use, in this work, the Sustainability Barometer methodology, applied together with indicators related to the municipality of Cuiabá.

Study area

The study area was the municipality of Cuiabá, located in the Central-West region of Brazil, with an estimated population of 623,614 inhabitants in 2021 (Figure 1).10 The Human Development Index (HDI) of the municipality, according to the 2010 IBGE census, was 0.785 and the population density was 157.66 inhab./km2.

This work constitutes a basic qualitative research, in which documents were selected, objectives and elements of analysis were defined, enabling the analysis of results, data collection through documentary research and, finally, the treatment and discussion of the results obtained. For this, a bibliographic, documentary11 and theoretical research was carried out, based on books and scientific articles, official documents, materials and information made available by the Municipality of Cuiabá, IBGE and the Department of Information of the Unified Health System (DATASUS).12 The layout of the location of the municipality of Cuiabá was prepared using the QGIS 3.18 software and the calculations regarding the values of the sustainability indicators were performed in Excel 2010. The themes were selected and adapted based on works by authors such as Prescott-Allen (1997), Durante et al.,13 among others, on the Sustainability Barometer methodology.

Selection of indicators

The selection of indicators to compose the Sustainability Barometer was made by consulting the IBGE’s “Sustainability Indicators”,14 with the necessary changes. The composition of the indicators was conditioned by the availability and consistency of the data. Therefore, data related to the period 2009-2019 were used. It was not possible to use the most recent data due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused the postponement of important surveys such as the IBGE Census. Therefore, the results may not reflect the current situation of the study area, as well as may differ according to the choice of indicators used and the period analyzed.

Regarding data collection, these were obtained secondarily from institutional websites, namely: IBGE, PNAD, PNUD, National Sanitation Information System (SNIS), Cuiabá City Hall and DATASUS.

The data were tabulated using the Excel program. First, the Environmental and Social Dimensions were presented; then, the indicators were divided by Theme, namely: Water, Air, Health, Housing, Education, Economy and Community/Security. To better understand each indicator used in this work, Table 1 contains descriptions related to the indicators. The information above was collected from materials made available by IBGE, Instituto Trata Brasil, Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) and authors such as: Campos, Oliveira and Périco (2020), Gloria, Horn and Hilgemann,15 Soares (2021) and Waldman and Sampaio (2019).

|

Dimension |

Theme |

Indicator |

Description |

|

Environmental |

Water |

Calculated water loss rate |

The level of water losses is a relevant index for measuring the efficiency of service providers in activities such as distribution, planning, investment and maintenance. These losses have a negative impact on the environment, on revenue and on companies' production costs, burdening the system as a whole and ultimately affecting all consumers (INSTITUTO TRATA BRASIL, 2020, p. 11). |

|

Water Quality Index |

According to the National Water Agency (2017), monitoring the quality of surface water is a key factor in the proper management of water resources; it allows for the characterization and analysis of trends in river basins, and is essential for various management activities, such as: planning, granting, charging and framing of watercourses (apud GLORIA; HORN; HILGEMANN, 2017). |

||

|

Air |

Highest polluting potential in the state |

The ozone layer is essential for maintaining life on Earth, as it absorbs most of the ultraviolet B (UV-B) radiation that reaches the planet and which is highly harmful to living beings. Therefore, by monitoring the evolution of the consumption of ozone-depleting substances, we are also evaluating the future risks to human health and quality of life (IBGE, 2015). |

|

|

Cuiabá's vehicle fleet |

|||

|

Social |

Health |

Infant mortality rate |

In general, it reflects the conditions of socio-economic development and environmental infrastructure, as well as access to the quality of resources available to maternal health and the child population available for maternal and child health (IBGE, 2015). |

|

Health establishments in the municipality of Cuiabá |

Universal access to health services is a prerequisite for achieving and maintaining the population's quality of life, which is one of the prerequisites for sustainable development. It is relevant because it expresses the supply of basic health service infrastructure and its potential for access by the population (IBGE, 2015). |

||

|

People aged 60 and over with health insurance (%) |

|||

|

Housing |

Households with adequate sanitation |

Adequate sewage disposal in the home is fundamental for the health of the population, helping to reduce the risk and frequency of diseases associated with sewage. Along with other indicators, it is an important indicator for characterizing the population's quality of life (IBGE, 2015). |

|

|

% of population in households with piped water |

Access to drinking water is fundamental to ensuring good health and hygiene. Together with other indicators, it becomes a good indicator of sustainable development, and is important for characterizing the population's quality of life and for monitoring public environmental sanitation policies (IBGE, 2015). |

||

|

% of population in households with electricity |

Sustainable development requires guaranteeing the right to adequate housing. According to the UN's Habitat II Agenda (1996), among the various elements necessary for housing to be considered adequate are: the provision of services essential to health, safety, comfort and nutrition. It therefore includes access to natural resources, drinking water, energy, household waste collection, etc. collection, among others (apud WALDMAN, SAMPAIO, 2019). |

||

|

% of population in households with garbage collection |

Solid waste management, especially in urban environments, has become an important mechanism for socio-economic and environmental development. This information is extremely important, providing an indicator that can be associated with both health and environmental protection environment (IBGE, 2015). |

||

|

Education |

Illiteracy rate (%) for people aged 10 and over |

In order to develop sustainably, a nation needs to make basic education accessible to the entire population, starting with literacy. The literacy rate, disaggregated by sex and color or race, is an indicator that shows educational inequalities, hindering the pursuit of social equity and therefore sustainable development (IBGE, 2015). |

|

|

Illiteracy rate (%) |

|||

|

% of children aged 11 to 13 attending the final years of elementary school |

Education is a priority for society and attending school guarantees individuals sociability in the school environment, the notion of individual and collective growth and the appreciation of formal knowledge, contributing to personal development, the continued acquisition of knowledge, as well as the adoption of healthier social and environmental practices (IBGE, 2015). |

||

|

% of children aged 5-6 in school |

|||

|

% of children aged 6 to 14 out of school |

|||

|

% of people aged 15 to 24 who do not |

Table 1 Description of sustainable development indicators

Source: Campos, Oliveira and Périco (2020), Gloria, Horn and Hilgemann (2017), IBGE (2015), IPEA (2004), Soares (2021), Trata Brasil Institute (2020), Waldman and Sampaio (2019).

The data presented in Table 2 were obtained from research carried out by IBGE, UNDP, the State Finance Department (SEFAZ), the Mortality Information System (MIS) and the Cuiabá Department of Environment and Sustainable Urban Development (SMADESS). The data period was 2009-2019.

|

Dimension |

Theme |

Indicator |

Source |

Year |

|

Environmental |

Water |

Calculated water loss index |

IBGE4 |

2017 |

|

Water Quality Index (WQI) of the Systems |

SMADESS9 |

2016 |

||

|

Air |

Greatest polluting potential in the State |

SEFAZ, IBGE7 |

2010 |

|

|

Cuiabá vehicle fleet |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

||

|

Social |

Health |

Infant mortality rate |

IBGE5 |

2019 |

|

Health establishments in the Municipality of Cuiabá |

IBGE1 |

2009 |

||

|

People aged 60 or over with health insurance (%) |

IBGE3 |

2013 |

||

|

Housing |

Households with adequate sanitation |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

|

|

% of population in households with running water |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

% of population in households with electricity |

UNDP4 |

2013 |

||

|

% of population in households with garbage collection |

UNDP4 |

2013 |

||

|

Education |

Illiteracy rate (%) for people aged 10 and over |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

|

|

Illiteracy rate (%) |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

||

|

% of children aged 11 to 13 attending the final years of primary school |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

% of children aged 5-6 in school |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

% of children aged 6-14 out of school |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

% of people aged 15 to 24 who do not study, do not work and are vulnerable to poverty in the population |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

% of people aged 18 or over who have not completed primary education and are in informal employment |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

Economy |

Gini index of per capita household income |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

|

|

% vulnerable to poverty |

UNDP6 |

2013 |

||

|

Unemployment rate |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

||

|

Community/Security |

Mortality rate due to land transport accidents (per 1000 inhabitants) |

SIM8 |

2011 |

|

|

Child labor rate (%) |

IBGE2 |

2010 |

Table 2 Sustainable development indicators

Source: 1 IBGE (2009), 2 IBGE (2010), 3 IBGE (2013), 4 IBGE (2017), 5 IBGE (2019), 6 UNDP (2013), 7 SEFAZ; IBGE (2010), 8 SIM (2011), 9 SMADESS (2016).

According to IBGE,14

The environmental dimension deals with pressure and impact factors and is related to the objectives of environmental preservation and conservation, considered fundamental for the quality of life of current generations and for the benefit of future generations. [...] The social dimension corresponds, especially, to the objectives linked to the satisfaction of human needs, the improvement of quality of life and social justice. [...] The economic dimension deals with issues related to the use and depletion of natural resources, the production and management of waste, the use of energy and the macroeconomic and financial performance of the country. [...] The institutional dimension concerns the political orientation, capacity and effort expended by governments and society in implementing the changes required for the effective implementation of sustainable development.14

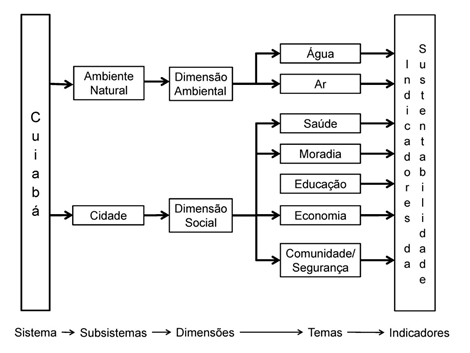

In this work, the indicators were divided into two dimensions: Environmental and Social, and subdivided by themes: Water, Air, Health, Housing, Education, Economy and Community/Security. Thus, the Sustainability Barometer methodology is applied using the indicators presented previously.

Next, the results related to this work are presented, which address reflections on housing chosen to present the example of the methodology studied.

Application of the sustainability barometer methodology

The methodology adopted in the development of this work is based on the references constructed by Prescott-Allen (1997), called the Sustainability Barometer.

In the second stage, the hierarchical structure proposed by Prescott-Allen (1997) was adapted, thus choosing two dimensions of sustainability: Environmental and Social, considering Cuiabá as the system and the natural environment and the city as subsystems (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Hierarchical structure for selecting sustainability indicators.

Source: Adapted from Rossetto et al. (2020).

In this way, a set of nine themes (Water, Air, Health, Housing, Education, Economy, Community/Security and Equity) and 23 (twenty-three) indicators were established, for which the sources/values and reference targets were chosen for the construction of the Local Performance Scale (LPS), contemplating national, state and global reference parameters and obeying the criterion of flexibility and relevance to the reality to be analyzed (Kronemberg et al., 2004).16

Subsequently, supported by the IBGE, a set of information was selected that covers the environmental, economic and social dimensions of the city of Cuiabá in order to select the indicators.

For each indicator, a Local Performance Scale (LPS) was established, according to the average of the values individually attributed to each of them by the researcher (Table 3). It is worth noting that in the Sustainability Barometer methodology, the indicator scales follow a direct logic, that is, the higher their value, the more sustainable the system. However, there are indicators that follow the opposite logic.16

|

Indicators (DLX) |

Unsustainable |

Potentially Unsustainable |

Intermediary |

Potentially Sustainable |

Sustainable |

|

Calculated water loss index |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Water Quality Index (WQI) |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

Greatest polluting potential ofandstate |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Cuiabá vehicle fleet |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Infant mortality rate |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Health establishments inmUniversity of Cuiabá |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

People aged 60 or over with health insurance (%) |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

Households with adequate sanitation |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

% of population in households with running water |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

% of population in households with electricity |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

% of population in households with garbage collection |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

Illiteracy rate (%) for people aged 10 and over |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Illiteracy rate (%) |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

% of children aged 11 to 13 attending the final years of primary school |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

% of children aged 5-6 in school |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

% of children aged 6-14 out of school |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

% of people aged 15 to 24 who do not study, do not work and are vulnerable to poverty in the population |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

% of people aged 18 or over who have not completed primary education and are in informal employment |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Gini index of per capita household income |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

|

% vulnerable to poverty |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Unemployment rate |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Mortality rate due to land transport accidents (per 1000 inhabitants) |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

|

Child labor rate (%) |

85 ˂ DLX ≤ 100 |

65 ˂ DLX ≤ 85 |

35 ˂ DLX ≤ 65 |

10 ˂ DLX ≤ 35 |

0 ˂ DLX ≤ 10 |

Table 3 Local Development Scale (LDS) of each indicatoror

Source: Adapted from Rossetto et al. (2020).

The Sustainability Barometer Scale (SBS), in turn, has the limits established as per Table 4.

|

0 < x ≤ 20 |

20 < x ≤ 40 |

40 < x ≤ 60 |

60 < x ≤ 80 |

80 < x ≤ 100 |

|

Unsustainable |

Potentially Unsustainable |

Intermediary |

Potentially Sustainable |

Sustainable |

Table 4 Sustainability Barometer Scale (SBS). Where “x” is the indicator analyzed

Source: Adapted from Prescott-Allen (1997).

Subsequently, data were sought for each indicator (DLX). Such numerical value DLX was transposed to the EBS, as illustrated in Figure 3, when the relationship between the indicator and sustainability is increasing and decreasing, respectively. Then, the value of the indicator was located in the EDL, as well as the previous points (DLA) and later (DLp). By aligning the five numerical values of the two scales (EDL and EBS), the relative position of the EDL on the EBS scale.

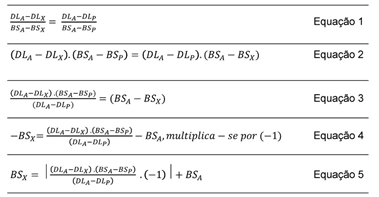

The transposition was performed by means of simple linear interpolation, in which a new data set is constructed (BSX) from a discrete set of previously known point data (DLA, DLp, BSA, BSp and DLX), as demonstrated by equations 1 to 5 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Equations to define the values corresponding to the transposition of DLA to EBS.

Source: Adapted from Prescott-Allen (1997).

Where:

DLX : Indicator value according to study data

DLA : Scale value immediately preceding DLA

DLp : Scale value immediately following DLA

BSX : Value corresponding to the transposition of DLA for the SBS

BSA : Scale value immediately preceding BSX

BSp : Scale value immediately following BSX

In this work, all indicators received equal weights, that is, they all had the same degree of importance. The values of BSp The calculated values are called Degrees. The analysis of the Sustainability Indicators was carried out in an integrated manner and in accordance with the sources/values and reference targets previously established for the Performance Scale. Following the assumptions of the BS, the dimensions were divided into two components: the Ecological Well-being Index and the Human Well-being Index, which aggregate the management of natural characteristics and social and economic issues, respectively (Prescott-Allen, 1997).16 These indices were calculated using the arithmetic mean of the indicators that composed them.

With the information and data collected previously, it was decided to convert all unit values to percentages (%). With this, the necessary calculations were performed using Excel software to obtain the values of each indicator in degrees. The results are presented in Table 5, so that they can be summarized and classified according to the Sustainability Barometer methodology.

|

Dimension |

Theme |

Indicators |

Indicator value (DLX) |

Degrees |

|

|

Unitary |

Percentage (%) |

||||

|

Environmental |

Water |

Calculated water loss index |

|

65.9 |

35.28 |

|

Water Quality Index (WQI) |

|

97.44 |

81.63 |

||

|

Air |

Greatest polluting potential in the State - INDAPP |

15.75 |

75.4 |

||

|

Cuiabá vehicle fleet |

448,698 |

19.32 |

72.54 |

||

|

Social |

Health |

Infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births) |

10.76 |

79.39 |

|

|

Health establishments in the Municipality of Cuiabá |

312 |

15.59 |

27.06 |

||

|

People aged 60 or over with health insurance (%) |

54.2 |

52.8 |

|||

|

Housing |

Households with adequate sanitation |

80.2 |

70.13 |

||

|

% of population in households with running water |

97.04 |

81.36 |

|||

|

% of population in households with electricity |

99.92 |

83.28 |

|||

|

% of population in households with garbage collection |

98.28 |

82.19 |

|||

|

Education |

Illiteracy rate (%) for people aged 10 and over |

5.04 |

83.97 |

||

|

Illiteracy rate (%) |

|

4.5 |

84.4 |

||

|

% of children aged 11 to 13 attending the final years of primary school |

86.65 |

74.43 |

|||

|

% of children aged 5-6 in school |

|

90.09 |

76.73 |

||

|

% of children aged 6-14 out of school |

4.2 |

84.64 |

|||

|

% of people aged 15 to 24 who do not study, do not work and are vulnerable to poverty in the population |

5.66 |

83.47 |

|||

|

% of people aged 18 or over who have not completed primary education and are in informal employment |

20.97 |

71.22 |

|||

|

Economy |

Gini index of per capita household income |

0.6008 |

60.08 |

56.72 |

|

|

% vulnerable to poverty |

|

17.21 |

74.23 |

||

|

Unemployment rate |

|

6.41 |

82.87 |

||

|

Community/Security |

Mortality rate due to land transport accidents (per 1000 inhabitants) |

32.9 |

61.68 |

||

|

Child labor rate (%) |

|

10.9 |

79.28 |

||

Table 5 Values assigned to each indicator (DLX)

Source: IBGE (2009), IBGE (2010), IBGE (2013), IBGE (2017), IBGE (2019), UNDP (2013), SEFAZ; IBGE (2010), SIM (2011), SMADESS (2016).

The results were divided by themes, with the classification corresponding to the range where the indicator is allocated on the Performance Scale, as well as the average and general classification of each theme (Tables 2–5).

According to the BS, the indicators used for this housing example were: “% of the population in households with running water”, “% of the population in households with electricity” and “% of the population in households with garbage collection” were considered as “Sustainable”, with values in Degrees of (81.36), (83.28) and (82.19), respectively. The indicator “Households with adequate sanitation” (Degree = 70.13) was considered “Potentially Sustainable”. Therefore, the average for the Housing Theme was 79.24, an indicator classified as “Potentially Sustainable” (Table 6).

|

Housing theme |

||

|

Indicator |

Percentage (%) |

Equivalence on the Local Development Scale (LDS) (Degrees) |

|

Households with adequate sanitation |

80.2 |

70.13 |

|

% of population in households with running water |

97.04 |

81.36 |

|

% of population in households with electricity |

99.92 |

83.28 |

|

% of population in households with garbage collection |

98.28 |

82.19 |

|

|

Housing Theme Average |

79.24 |

Table 6 Result of the housing theme indicators on the performance scale

Source: IBGE (2010), IBGE (2013).

However, according to data from the Trata Brasil Institute, in 2007, Cuiabá declared that it treated 29% of its sewage and only 14% in 2008 (Instituto Trata Brasil, 2010) and, according to the 2010 sanitation ranking by the Trata Brasil Institute (2012), in relation to the Total Sewage Service Indicator (%), Cuiabá presented a result of 39.90% and 21.9% in the Sewage Treated by Water Consumed Indicator (%). Overall, Cuiabá occupied the 84th position in the ranking of the 100 largest municipalities analyzed (Figure 5). The institute also analyzed the evolution in total sewage collection and sewage treatment during the period from 2015 to 2019 and Cuiabá presented an increase of 12.79 and 25.75 percentage points, respectively, with 61.62% of total sewage collection and 52.85% of sewage treatment in 2019 (Instituto Trata Brasil, 2021).

According to information from the 2014 Municipal Basic Sanitation Plan,17 approximately 38% of the population is served by the sewage system, and only 28% of these have collection and treatment services. And, according to Silva,18 the Cuiabá River receives 4.3 liters per second of sewage every day, from the state capital alone, and less than 20% of this sewage is treated in Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs).19

Therefore, universal and quality access to basic sanitation is still a major challenge, and the deficits in this sector show that basic rights are not always guaranteed (Brum et al., 2016). Rodrigues and Pedreiro20 emphasize that:

If things continue like this, conditions will become increasingly unpleasant, especially for the less privileged part of the population, who live in precarious conditions, with a lack of basic sanitation for water treatment and even no water at all. Given that water is essential for health, the lack of it will increasingly lead to an increase in diseases and a decrease in life expectancy.

In order to protect the health of the population and preserve the environment, it is necessary to provide adequate treatment of collected sewage,21 since inadequate management affects all other areas of sanitation (sewage, water supply and urban rainwater drainage) (Moraleco et al., 2014).17 It is also important to create a program to recover riparian forests, streams and effluent from the Cuiabá River and to build new sewage treatment plants that operate efficiently, seeking to improve water quality (Figure 6).19,22–26

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many surveys were not conducted, such as the IBGE census. Therefore, the most recent data were not used in this study. It is worth noting that these results correspond to these indicators and to this period; therefore, when applying the BS methodology to other indicators, the results may be different from those obtained in this study. Therefore, the results of this study indicate that, although the city of Cuiabá is on the Sustainability Barometer scale as “Potentially Sustainable”, there is still much to be done.

Despite the global awareness of the environmental problem and the progress represented by the implementation of environmental policy in the specific Brazilian case, it is believed that the greatest obstacle lies, in fact, in the value attributed to natural resources.1 Theoretical-methodological conceptions and groups with different political identities have specific worldviews and, therefore, different conceptions about environmental problems, which subject humanity to the impacts of diverse phenomena and create situations of instability and uncertainty that require individual and collective actions to be overcome or, at least, minimized.6 Therefore, sustainability must be a daily struggle and achievement19 and involve everyone. Thus, this work aimed to apply the Sustainability Barometer methodology in the municipality of Cuiabá, using the indicator system, to assist in verifying the levels of sustainable development of the municipality, in decision-making and in the formulation of public policies.

None.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest in writing the manuscript.

©2025 Nora, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.