MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2919

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Institute of Geosciences of the Federal University of Pará, UFPA, Campus Universitário do Guamá, Brazil

2Department of Chemical Engineering, Polytechnic School, University of São Paulo, USP, Brazil

Correspondence: Luiz Kulay, Department of Chemical Engineering, Polytechnic School, University of São Paulo, USP, Av. Prof. Lineu Prestes, 580, Zip Code: 05508-000, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Received: February 17, 2025 | Published: February 28, 2025

Citation: Laban DOC, Rodrigues JP, Reche LL, et al. Accounting for carbon in a palm oil production system in Eastern Amazonia. MOJ Eco Environ Sci. 2025;10(1):44-50. DOI: 10.15406/mojes.2025.10.00345

In eastern Amazonia, favorable environmental conditions primarily drive the expansion of oil palm plantations. This increase in cultivation has led to the growth of palm oil extraction companies in the region. However, establishing the sector has also resulted in escalating environmental impacts. This study aimed to calculate the balance of Greenhouse Gases (GHG) emitted during palm oil production, focusing on CO2 sequestration in interspecific hybrid palm plantations (HIE: Elaeis oleifera Cortes x Elaeis guineensis Jacq.).

The aerial biomass of HIE was estimated in plantations at one, three, five, and eight years of age. The biomass content at 25 years (the end of the economic cycle) was determined using the Chapman-Richards function, with a carbon conversion factor of f = 0.47. The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) technique accounted for GHG emissions throughout palm oil production.

Over 25 years, with an area of 2,645 hectares occupied by interspecific hybrid palm, the total carbon sequestered was estimated at 0.49 kilotons of CO2eq per hectare. In comparison, the total GHG emissions from the production process were approximately 0.39 kilotons of CO2eq per hectare over the same time frame. These findings suggest that the carbon balance of hybrid palm-HIE plantations, under the assessed conditions, is favorable due to significant carbon sequestration. At the same time, the GHG emissions associated with palm oil production are comparatively low.

Keywords: oil palm, carbon accounting, climate change

Palm oil is a significant global commodity due to its diverse applications, including food processing, cosmetics manufacturing, and biodiesel production.1,2 It is a perennial crop characterized by a long growing season and high biomass production, with an average economic lifespan of 25 years.3,4

Globally, the leading palm oil producers are Indonesia and Malaysia. In 2021, Indonesia cultivated nearly 29 million hectares (Mha) of palm oil, fabricating almost 50 million tons (Mt) of oil. Malaysia manufactured 18 million tons of oil from 5.1 million hectares in the same period. Brazil ranked tenth in the production of the commodity, generating 579,000 tons (Kt), primarily from cultivating Elaeis guineensis, from the Ternera variety, on just over 0.2 million hectares.5 However, about 31 million hectares of land in Brazil are suitable for oil palm plantations, particularly in the North Region, where the climatic and environmental conditions are quite favorable for the growth of this crop.6

According to Ritchie,7 deforested regions could benefit palm cultivation. Converting deforested areas into oil palm plantations could provide significant environmental advantages, such as carbon sequestration, partial restoration of hydrological changes caused by deforestation, and a reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with the palm oil production cycle.8,9

It is important to note that studies estimating CO2 sequestration in oil palms with interspecific hybrids are limited. Most research focuses on oil palm cultivation with intraspecific hybrids, primarily in Indonesia and Malaysia.10–15 In Brazil, information about CO2 sequestration is obtained mainly from studies by Frazão et al.16, Sanquetta et al.17, Cassol et al.18, and more recently, Murphy.19

Carbon accounting in this context was conducted using the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) method in the attributional modality and for a scope from 'cradle-to-gate.' This systemic approach considered the technological aspects and operational circumstances of the agricultural and industrial subsystems and the emissions generated by these operations.

The study sought to evaluate the potential of planting an interspecific hybrid (HIE) (Elaeis oleifera Cortes vs. Elaeis guineensis Jacq) in deforested areas of the Amazon to offset greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions throughout the oil production cycle. We expect the findings obtained from this scientific effort can support decision-making processes and further research within this production chain to reduce GHG emissions released into the atmosphere.

The methodology employed in this research comprised of the following steps:

Study area

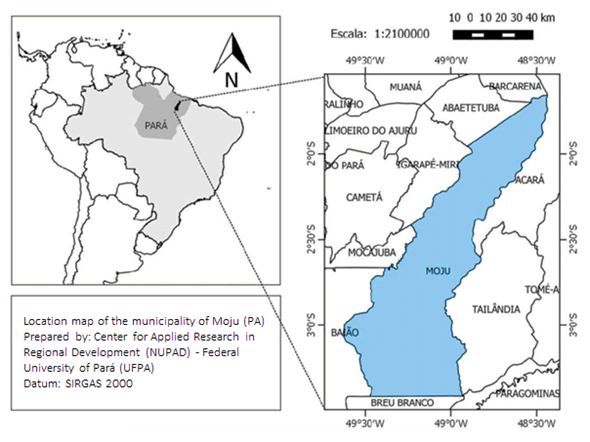

The study area is in Moju, located at 1°58’42” S latitude and 48°36’50” W longitude, in northeastern Pará, Brazil (Figure 1). This region features edaphic and climatic conditions that are favorable for the cultivation of oil palm. According to the Köppen climate classification,20,21 the area has a humid equatorial climate, with average annual rainfall between 2,000 and 2,500 mm.22,23 The soil is characterized by average clay content, ranging from 18% to 29%, and is classified as a typical dystrophic Yellow Latosol in the Brazilian Soil Classification System.24,25

Figure 1 Geographical location of the study area: Municipality of Moju (PA).

Source: IBGE vector base (2016)

Description of the production process

As shown in Figure 2, the palm oil production cycle consists of two main subsystems: agricultural and industrial. The agricultural subsystem includes the following activities: cultivating in nurseries, preparing the soil, managing crops, producing and applying fertilizers and agrochemicals, and harvesting and transporting fresh fruit bunches (FFB) to the processing facility.

The industrial subsystem encompasses several key stages of the manufacturing chain: receiving the harvested fruit, extracting palm and palm kernel oils, generating pressed fruit cake as a byproduct, conducting electrical cogeneration through a combined steam cycle system powered by burning biomass (including fibers and shells), and treating the produced effluents. The technological and procedural details of each subsystem are discussed below.

Agricultural subsystem

The first stage of the agricultural subsystem involves preparing the soil for planting seedlings. This process includes removing vegetation and clearing the land to create a suitable planting area while leaving surface biomass that can provide nutrition for the soil. Next, in the nursery, seeds are converted into seedlings, which are then ready for planting. Water and agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides are added at this stage. Specific machinery, including tractors (with and without harrows), mowers, and loaders, is used for planting and cultural treatments.26 Fertilizers are applied as primary macronutrient sources – nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) – as well as secondary sources – boron (B), magnesium (Mg), and calcium (Ca) – and micronutrients such as zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu). These active ingredients are transported by road, covering an average distance of approximately 2,100 km. The pesticides used in the agricultural subsystem include insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides.27

Three years after planting, the palm fruit bunches (PFBs) are ready for harvesting, a process carried out manually. The harvested product is transported from the agricultural area in carts pulled by mules and buffaloes and transferred to containers at the edge of the cultivation areas. Transportation from these areas to the industrial unit is conducted by truck over a distance of about 15 km.27 Palm cultivation in the Moju region typically lasts for approximately 25 years. After this period, agricultural processing tends to become uneconomical.4

Legend: The steps or operations marked with narrow lines were not considered for modeling the system under analysis and were thus excluded from the environmental performance assessment.

Industrial subsystem

The industrial subsystem encompasses the operations that begin with the receipt of the Crude Fruit Feed (CFF) and continue until the extraction of oil and cake. The initial process involves transporting the fruit bunches to the sterilization unit using wagons with an average load capacity of 5.0 tons. This is followed by sterilization, which eliminates enzymes responsible for the fermentation of fresh fruit, detaches these elements from the bunches, softens the pulp to facilitate oil extraction, and shrinks the nuts to improve shell removal efficiency. This process occurs in batches within an autoclave that can process up to 4.0 tons of material. During sterilization, the bunches are directly exposed to superheated steam at a pressure of 3.0 kgf/cm² and 140–145°C for approximately 60 minutes, completing one cooking cycle.28

Once sterilization is complete, the loader pushes the wagons to a tipper, which feeds an electrically driven conveyor belt. The sterilized bunches are then directed to a thresher, which operates at a throughput of 4.0 to 8.0 tons per hour. This equipment separates the fruits from the remaining biomass, primarily empty bunches. This byproduct accounts for approximately 20-25% of the total mass of processed CFF and is typically repurposed as a carbon source for fertilizing fields or as energy to fuel the boiler.29

The collected fruits are delivered via a chute equipped with a screw conveyor to a bucket elevator, which transports them to the press digesters. In the digester, the fruits are subjected to temperatures between 90–95°C through direct steam contact for 25-30 minutes before pressing. This pressing process yields crude oil and a solid residue composed of fibers and nuts. The generated water is directed to an effluent collection pool, and its suspended solids are converted into fertilizer.30

The fiber (a lighter fraction of the solid extract) is sucked up and conveyed through a pipeline for use as boiler fuel. Like thebunches, any excess fibers are returned to the plantations as fertilizer. The nuts (heavier fraction) are disintegrated in a rotating cylinder before being transferred to a storage silo using a screw conveyor. The nut shells are extracted and sent to the boiler for fuel during this transit due to their high Lower Calorific Value (20.8–21.4 MJ/kg). Excess shells, like the fibers, are returned to the fields as bedding for nurseries. After shelling, the almonds proceed to a drying silo. In preparation for the oil extraction, the nuts will pass through a gravity table that separates them from any remaining shells. They are then crushed, cooked to remove moisture, and pressed to extract the oil, which occurs in an electromechanical press with an average processing capacity of 3.0 to 6.0 tons per hour of fruit. The transformation yields oil and produces a pressed fruit cake (or mass), constituting 25% of the processed bunches and initiating the palmistry process.31

Estimates of carbon emissions from this subsystem were based on the assumptions that 5.0 tons of CFF yield approximately 1,000 kg of palm oil, 57 kg of palm kernel oil, 128 kg of palm kernel cake, as well as generating 998 kg of empty bunches, 764 kg of fibers, 73 kg of husks, and 1,902 kg of liquid effluent, or the Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME).

Preparation of an inventory of emissions and carbon accumulation

Estimation of GHG emissions associated with the process

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and carbon fixation flows from palm due to photosynthesis related to the oil manufacturing cycle were determined using the Life Cycle Assessment technique in the attributional modality and through a cradle-to-gate approach. Therefore, GHG emissions associated with post-production stages (product distribution, use, and final disposal) were excluded from this analysis. The Reference Flow (RF) established for estimates corresponds to 1,000 kg of processed palm oil of sufficient quality for commercialization. Table 1 presents data and general information on the cultivation of HIE provided by the company Marborges Agroindustrial S.A.

|

Parameter |

Unit |

Variation range |

|

Total plantation area |

ha |

2,500 – 2,700 |

|

Planting density |

Plants/ha |

135 – 162 |

|

Total Number of plants |

number |

350,000 – 385,000 |

|

CFF production |

Mg/ha |

15.2 – 23.7 |

|

Average palm oil production |

Mg/ha |

3.50 – 6.00 |

|

Crop life cycle |

years |

25 ± 2.0 |

Table 1 General data and information about HIE Plantations in Eastern Amazonia

Source: Empresa Marborges Agroindustrial S.A

Except for those related to transportation operations, all data used to prepare the inventory are of primary origin. These parameters were collected from measurements taken in the field. They were then verified for consistency and homogeneity using material and energy balances and by comparing values available in the literature.

Data collection encompassed land use changes, fertilizer and agrochemical usage, process water, and fuels used to operate machinery in agricultural operations. This survey was conducted over four years, from 2012 to 2015. Although they may seem outdated, the data remained consistent and representative of the technologies and operational practices used in the agricultural and industrial subsystems when compared to the corresponding, and much more recent, parameters available in Ferreira,32 Silva,33 Sousa,34 Cardoso,35 Menezes et al.,36 and Santos et al.37

The inventory was prepared using average values from the variation intervals of those parameters. To achieve this purpose, statistical methods were applied to the historical data series after removing non-typical values (outliers) that represented extreme or infrequent conditions. Only CO2, CH4, and N2O were included in this analysis, as they represent the most significant greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural and industrial subsystems of palm oil production and transportation operations.

The nursery's irrigation water consumption was estimated at 22,497 mm/RF. Fertilizer demands, in the form of primary macronutrients, corresponded to 40.0 kg N/RF, 33.9 kg P/RF, and 61.1 kg K/RF. Conversely, the consumption of the secondary macronutrients and the micronutrients was considered neglectable. Fuel demand was associated with irrigation in the nursery and the operation of agricultural equipment. Together, these needs amount to 14.6 kg diesel/RF. Biological pest control was modeled assuming doses of insecticides (pyrethroid-based), fungicides (Methyl Thiophanate), and herbicides (glyphosate).

The inventory of transportation emissions was obtained from the Ecoinvent database in version 3.2.38 This modeling was performed considering Euro 4 trucks powered by diesel and with a load capacity of 15 t. Furthermore, an average distance of 15 km was adopted between the palm cultivation area and the oil extraction unit.27 Table 2 describes the inventory of GHG consumption and emissions for the agricultural subsystem related to producing 1000 kg of palm oil.

|

Inputs (/RF) |

|||

|

Process stage |

Unit |

Average values |

|

|

Fertilizer (N – P – K) |

kg |

135 |

|

|

Agrochemicals |

g |

370 |

|

|

Harvesting (mules and buffaloes) |

head |

0.1 |

|

|

Diesel (agricultural machinery) |

kg |

14.6 |

|

|

Diesel (transportation) |

kg |

3.09 |

|

|

Outputs (/RF) |

|||

|

Emission |

Stage/Operation |

Unit |

Average values |

|

CO2 |

Soil preparation |

kg |

49.8 |

|

Fertilizer application |

kg |

8.52 |

|

|

Transporte |

kg |

10.5 |

|

|

CH4 |

Soil preparation |

g |

41.2 |

|

Fertilizer application |

g |

32.7 |

|

|

Harvesting |

kg |

1.82 |

|

|

Transportation |

g |

8.7 |

|

|

N2O |

Soil preparation |

g |

1.25 |

|

Fertilizer application |

g |

5.41 |

|

|

Transportation |

mg |

264 |

|

Table 2 Inventory of input consumption and GHG emissions: agricultural subsystem

Electricity is a vital energy resource in the industrial subsystem of oil extraction. Therefore, 173 kWh are needed to produce 1,000 kg of palm oil. Steam is produced by burning biomass from the CFF, generated from fibers (573 kg/RF) and husks (54.8 kg/RF). Additionally, the process produces 2,235 kg/RF of process effluents. Table 3 presents the inventory of the industrial subsystem and the associated GHGs.

|

Inputs (/RF) |

|||

|

Energy resources |

Unit |

Average values |

|

|

Electricity |

kWh |

173 |

|

|

Fibers and husks |

kg |

628 |

|

|

Outputs (/RF) |

|||

|

Emission |

Stage/Operation |

Unit |

Average values |

|

CO2 |

Electricity |

kg |

11.1 |

|

Fibers and husks |

kg |

621 |

|

|

POME |

kg |

49.5 |

|

|

CH4 |

Electricity |

g |

3.42 |

|

POME |

kg |

26.8 |

|

|

N2O |

Electricity |

g |

6.87 |

|

POME |

mg |

112 |

|

Table 3 Inventory of input consumption and GHG emissions: industrial subsystem

Total atmospheric CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions were calculated, and their contributions to global warming were assessed. This conversion involved multiplying each quantity by its corresponding impact factor. The values for each substance were sourced from the IPCC.39 After this mathematical operation, they share a standard unit (kg CO2eq/RF), allowing these contributions to be summed, resulting in a single impact result for the analyzed system.

Estimation of the rate of carbon accumulation by biomass

Ten plants aged one, three, five, and eight years were selected from the HIE crop. For this study, the following parameters were determined:

Similarly, the dry mass of each element was estimated. For this purpose, approximately 500 g samples of material (leaves, stems, petioles, rachises, leaflets, arrows, meristems, inflorescences, and fruits) were collected, weighed, and transported to the laboratory for drying in an oven at a temperature of 65°C until a constant mass was reached. The biomass content at 25 years was determined using the adjusted Chapman-Richards function,40 as described in Equation 1 (Eq. 1) below.

(1)

Where:

: Predicted biomass

: Maximum biomass obtained

t: crop age (years)

k: correction factor for the accumulation rate

m: correction factor that modifies the plant growth profile

This study analyzes the conversion of aboveground biomass carbon into biomass mass per hectare (expressed as Mg C/ha) using a factor of f1= 47%.17,41 According to Hamburg,42 considering that 50% of the population employed in the field may be excessive for E. guineensis prompted the IPCC43 to revise its standard. The conversion of carbon into CO2 was done by multiplying the total amount of carbon (C) by f2= 3.67, corresponding to the molar ratio defined between both chemical species.43 The current version of this report, IPCC,39 retains the assumptions and conventions of the previous edition.

Regarding the performance of the agricultural subsystem, an impact in the form of global warming of 445 kg CO2eq/RF was observed (Table 4). In this case, the primary contributions are associated with fertilizers (345 kg CO2eq/FU). During palm cultivation, from the initial nursery stage to the completion of the HIE crop cycle, an average of 1087 kg of NPK/ha is required, and its production and application result in the release of approximately 9.0 Mg CO2eq/ha into the atmosphere, a value close to that reported by Rodrigues et al.44

|

Process stage |

CO2 (kg/RF) |

% contribution |

CH4 (kg/RF) |

% contribution |

N2O (kg/RF) |

% contribution |

CO2eq (kg/RF) |

|

Agricultural subsystem |

|||||||

|

Fertilizers |

286 |

82.9 |

8.9 |

2.58 |

49.9 |

14.4 |

345 |

|

Mechanical operation |

49.8 |

97.5 |

0.86 |

1.69 |

0.39 |

0.76 |

51 |

|

Corp transportation |

- |

- |

38.2 |

100 |

- |

- |

38.2 |

|

CFF transportation |

10.5 |

97.6 |

0.18 |

1.7 |

0.08 |

0.76 |

10.7 |

|

Industrial subsystem |

|||||||

|

Electricity |

11.1 |

79.6 |

0.72 |

5.15 |

2.13 |

15.3 |

13.9 |

|

POME |

49.5 |

8.08 |

563 |

91.9 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

612 |

Table 4 GHG emissions and their respective impact on Global Warming

The industrial subsystem's total impact was 626 kg CO2eq/RF, with POME contributing 612 kg CO2eq/RF. This value is near the lower limit of the variation range, which spans from 625 to 1476 kg CO2eq/RF, as Choo et al.45 reported under conditions similar to those in this analysis. The high emissions from POME result from CH4 releases linked to anaerobic processes; according to Althausen,46 roughly 12.0 kg CH4 per ton of effluent is emitted during a typical process.

Regarding the combustion of bark and fibers, which produced 621 kg CO2/RF, the global warming impact factor for biogenic CO2 emissions is negligible.47 Biogenic CO2 emissions are balanced by the CO2 uptake during palm growth through photosynthesis. However, for the total greenhouse gas emissions analysis, 595 kg CO2eq/RF from trunk and leaf decomposition emissions were included, following the proposal by Rodrigues et al.44

In terms of carbon fixation, the study estimated that the aboveground biomass in HIE oil palm plantations was 108 Mg/ha at 25 years (Table 5), a figure consistent with estimates from palm plantations (non-hybrid genetic material) in Malaysia48 and Brazil.18 Variability in biomass arises from differences in genetic traits, soil and climate conditions, age, structure, and leaf arrangement.49

|

Age |

Aboveground biomass |

Carbon rate |

CO2 |

|

Anos |

Mg/ha |

Mg/ha |

Mg/ha |

|

1 |

0.93 |

0.44 |

1.6 |

|

5 |

40.5 |

19 |

69.8 |

|

10 |

62.8 |

29.5 |

108 |

|

15 |

77.8 |

36.5 |

134 |

|

25 |

108 |

50.6 |

186 |

Table 5 Aboveground biomass accumulation and carbon sequestration in HIE per hectare

Based on the system's process conditions under analysis, an accumulation of 50.6 Mg C/ha over 25 years was estimated (Table 5). This result aligns with the value reported by Silva et al.,50 which is 44.7 Mg C/ha for a plantation of the same age in Northern Brazil and 36 Mg C/ha in Malaysia.51,52 De Lara53 states that accumulation differences depend on each ecosystem's physiology and dynamics.

Our study estimated that cumulative CO2 sequestration over 25 years is 186 Mg CO2/ha, which falls within a wide range of variation reported in the literature, around 129.3 ± 227.1 Mg CO2/ha.54 Values exceeding 230 Mg CO2eq/ha in 20-year-old commercial plantations of non-hybrid genetic material were reported by Syahrinudin55 in Indonesia. Considering this performance for the oil palm cultivation cycle, it is estimated that across the agricultural area occupied by the company with HIE (2,645 ha) and in the HIE palm production cycle (25 years), the fixation rate would be 490 kt CO2. In the same timeframe, the GHG emissions generated throughout the palm oil production cycle amount to approximately 390 kt CO2eq. Thus, the process yields benefits regarding the impact of roughly 1.25 times due to the positive balance between GHG emissions and CO2 sequestration. This estimate is consistent with studies by Rodrigues et al.,44 which reported compensation values of 1.1 and 2.0 times, respectively, for similar circumstances. Therefore, considering the composition of all quantified effects, it is clear that the balance of carbon sequestration (CO2eq) in HIE plantations is positive for cases where the area occupied by oil palm plantations was previously pastures.53,56–58

In the current climate change scenario, it is essential to identify various mechanisms for mitigating or offsetting GHG emissions across different ecosystems. Given their significance for regional development, one such mechanism is oil plantations in the Amazon. Oil palm plantations featuring interspecific hybrids (HIE) in pasture areas have demonstrated a strong capacity for carbon sequestration and mitigating GHG emissions throughout palm oil production (both agricultural and industrial phases).

The benefits of carbon sequestration from palms are equally important in terms of their impact on global warming. Thus, the outcome endorses decision-making processes for offsetting greenhouse gas emissions. If sustained throughout their lifecycle (at least 25 years), this would enable long-term sustainable palm oil production in Eastern Amazonia.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior/Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Brazil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest in writing the manuscript.

©2025 Laban, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.