MOJ

eISSN: 2572-8520

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 4

Department of Urban & Regional Planning, Rivers State University, Nigeria

Correspondence: Brown Ibama, Department of Urban & Regional Planning, Rivers State University, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Received: December 26, 2019 | Published: December 31, 2019

Citation: Eyenghe, Tari, Ibama B, et al. Dynamics of gentrification: experiences from selected neighbourhoods in Port Harcourt municipality. MOJ Civil Eng.2019;5(4):107-113. DOI: 10.15406/mojce.2019.05.00163

In recent times gentrification in the form of urbanisation has become a prominent recurrent phenomenon dotting the cityscape on most developing cities in the global south. Little attention has been given to the process because the dynamics of gentrification has become more challenging to city managers in Port Harcourt Municipality in Nigeria. This study aims to highlight specific areas inundated with gentrification within selected neighbourhoods of Port Harcourt Municipality such as Orije Old GRA, Oromenike (D/Line) and PH-Township with characteristics of three residential densities (low, medium and high) respectively. Identify causal factors with a view to understanding the dynamics and recommend planning measures that would ameliorate associated identified impacts. Mixed method approach was deployed. A total of 397 respondents across three selected neighbourhoods participated with the aid of closed and open-ended questionnaires to obtain the data. Findings indicate significant changes in the neighbourhoods different from their original designated uses: from residential to mixed uses (commercial and residential) with impact on the social and economic conditions of these neighbourhoods. Sustained demand for space for other uses in addition to increasing population result in sudden spike in rent for residential and other uses. The study recommends intensive periodic review of existing planning schemes establishing these neighbourhoods by both government and relevant physical planning agencies as this would upgrade the neighbourhoods to more sustainable and modern urban environment; construction of more low-cost housing units in these neighbourhoods especially in the high and medium densities neighbourhoods for residents to ameliorate the high rental values of existing properties; introduction of rent control mechanisms to checkmate arbitrary increase in rent in the neighbourhoods, discourage unapproved change of use; and strict penalties according to the Rivers State Physical Planning and Development Law of 2004 to developers that violate the alteration of buildings without permit and going against the conditions of the permit issued to the developers to alter any building.

Keywords: dynamics, gentrification, neighbourhood, urbanization, demographic developments

In recent times gentrification has gained increased popularity and manifestation in urban planning and management lexicon. This manifestation has transformed both socioeconomic and demographic developments of global urban landforms in many cities. Gentrification is viewed as a social and economic process involving renters, private developers and individual homeowners invest in seemingly abandoned neighbourhoods to revive them socio-economically (Perez, 2004). The process of gentrification occurs with palpable alterations in demographic and economic landscape of cities aimed at attracting new residents and commercial activities.1 The evolution of cultural landscapes of some developed cities such as New York, London, Paris and Stockholm occasioned by rapid urbanisation at the behest of the delivery of efficient public and private transportation system, engendered the development of inner cities. As a result of this emergence, neighbourhoods in many cities across the globe once filled with working class, are now filled with young professionals paving way for multi-million-dollar condominium and accommodation for high income earners with commensurate high rentals.2

Cities in developing countries such as Port Harcourt municipality, Nigeria has witnessed rapid urbanisation with its attendant unprecedented surges in rental values and physical changes to the cityscape. This phenomenon has given rise to unprecedented surge in housing demand, urban infrastructure and services. In addition to that, there is rapid formation of informal settlements in the form of squatter settlements and slums which further degrade the environment and adjoining neighbourhoods within the municipality.3

Several attempts at urban development planning and management in developing countries such as Nigeria have been made with limited success. The causes of gentrification are widely debated but its symptoms are identical and progressive in nature.4 Over the past decade, Port Harcourt municipality and adjoining neighbourhoods have experienced surges in rental values of residential properties. Surges in rental values are occasioned by the changes in the housing stock underpinned by gentrification which has also changed the demography due to concomitant population surges. Buildings are altered from their original uses to reflect existing demand from residential to other uses including physical appearance totally changing the landscape and forms of the neighbourhoods. Low-income residents and some emerging businesses in the neighbourhoods oftentimes bear the brunt of gentrification. The research focuses on the nature and extent of gentrification on selected residential neighbourhoods in Port Harcourt municipality in Rivers State, Nigeria. The assessment is to identify the impacts of the nature and extent of the level of changes this gentrification has caused in the neighbourhoods and what has contributed to these experiences observed in the municipality

At the turn of the century Port Harcourt municipality has witnessed rapid physical, economic and social changes as a result of gentrification leading to massive displacements. Gentrification could be viewed as a positive development necessary for most developing cities; it has the capacity to create better infrastructure and services to attract people of higher classes into the neighbourhoods. However, the major challenge of gentrification is its occurrence in low-income neighbourhoods and the attendant displacement of such residents. There is the need to monitor identified alterations in neighbourhoods of the municipality to understand the nature and extent of the gentrification. In most circumstances, existing structures are often altered to accommodate mixed uses away from originally designated use with no appropriate management plan that would sustainably improve the standard of living and quality of the neighbourhood.

The aim of the study is to assess the nature and extent of gentrification in selected neighbourhood in Port Harcourt municipality. To achieve the aim of the study the following specific objectives are:

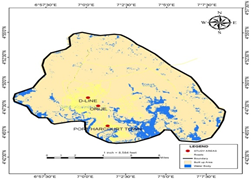

The study geographically covers Port Harcourt municipality spotting gentrified neighbourhoods (Figure 1,2) such as Orominike layout, Port Harcourt Township and Orije layout to identify, examine the nature and causes of gentrification to ascertain its impact.

Figure 1 Map of Nigeria showing rivers state, and rivers state showing Port Harcourt city LGA.

Source URP GIS lab, rivers state university, 2019

Figure 2 Map of Port Harcourt city LGA showing the study area

Source URP GIS lab, rivers state university, 2019

Urban planners and urban sociologists have over the years given significant attention to gentrification. Glass.,5 describes gentrification as a displacement process where original poor working-class residents are dislodged from neighbourhoods due to influx of wealthier residents and concomitant rising costs of goods and services in such neighbourhood. In the opinion of Kilmartin.,6 gentrification involves the process where higher income households displace lower income residents of a neighbourhood, which results in changes to the essential character and flavour of that neighbourhood.

Three distinct characteristics are synonymous with gentrification in the descriptions so far which include;

Consequently, once the process of gentrification begins in a neighbourhood, it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced and the whole social character of the neighbourhood changes to reflect new physical and social form.7 The process often fast paced, powerful and often alarmingly reshapes the physical and social form of such neighbourhoods and impact on the lives of residents.8

Gentrification in its form and character, does not only engender displacement of low-income groups in a neighbourhood, but mostly take place in the inner-city where the working-class and low-income groups reside. It also involves the rehabilitation and upgrading of buildings in residential neighbourhood which is associated with increase in the value of properties. As a result of the upgrade, rental value increases which attract other land-uses order than the residential use to high-class mixed uses. Gentrification as a concept is often confused with urban renewal but is distinct. Gentrification connotes displacement low-income residents in a neighbourhood driven by the private sector.5 Urban renewal is a deliberate effort by government and other development partners to rehabilitate, redevelop and upgrade neighbourhoods within the city that are socially, physically and economically run-down. This process is often implemented through informed planning of an existing neighbourhood or section of city to meet present and future needs of the residents to reside, work and recreate.9

Several factors that engender gentrification have been identified such as political, social and economic in most urban centres.10 asserts that gentrification is engendered by the supply-side theory where investors and capitalists after experiencing losses or limited profit investing in suburban and affluent areas, tend to create new urban spaces and revitalize deteriorated neighbourhoods. Profit making is the main driver of investors in such neighbourhoods. These neighbourhoods are carefully selected for investment based on proximity to job centres or potential for becoming job centres with viable economic prospects and conditions of the environment. The limited supply of land for housing development, meet housing demand from the bases of investing in the neighbourhoods to keep rent high and make more profit.10 For instance, gentrification in Switzerland is driven by real estate developers supported by local authorities through tax breaks and kickbacks instead of middle-class income earners.11 Provision of newer urban infrastructure and services also attract businesses and investors as the case of Chicago city.12 Neo-liberal policies and globalization are also contributory factors to the changing socioeconomic landscape of inner cities as private firms invest in public housing provision in other countries instead of local governments for profit making objective.13

Politically, factors that influence gentrification are deliberate government policies and actions through urban planning and development strategies. These policies and actions often force low-income earners to relocate to other sections of the city and suburbs through zoning schemes, subdivision regulations, landuse planning and management. Non-funding of public housing programmes by the government can also prompt gentrification process,14 such deliberate inaction often leads to displacement people.15

Economic factors leading to gentrification are linked to political forces, because deliberate neglect of inner city by government allows investors to take over the redevelopment of the inner city as most time they control economic resources with the ability to influence the politics of the city. Politicians are reluctant to wrest power from such investors as they finance most of the electioneering processes. Reluctance of taking control of activities of perceived potential investors within the cityscape often affect the inner-city residents who mostly are the urban poor and unrepresented voiceless majority in society.16

Social factors in the form of cultural diversity also fuels gentrification as it encourages migration of high-income earners to inner city neighbourhoods. There is fusion of culture, lifestyle and social alliance and networking that suburb neighbourhoods suffer from as families are isolated from one another.

According to17,18 the effects of gentrification in neighbourhoods are both positive and negative. These effects include:

Marginalisation, social exclusion discrimination between social groups especially (high and low-income groups and among ethnic groups); and Uneven development and promotion of capitalism within socioeconomic context.

All these factors affect gentrified neighbourhoods and portray physical, social and economic distortions of the cityscape. However, these conditions do not portray gentrification in all its ramifications as negative influence; rather it is aimed at revitalising neighbourhoods to meet current trends in urbanism and cultural distribution in cities. On the overall, gentrification is expected to be a sequentially planned out and managed process aimed at ameliorating the effects on various classes of people within the city to reduce the shock experienced by the voiceless in the society

The population of the study neighbourhoods from the 1991 population result was 40,228 and projected to 2019 is 234,528 at 6.5% growth rate in urban areas in Nigeria.19 The study employed mixed method approach with stratified simple random sampling techniques and key informant interviews for data collection. Primary data was obtained from residents of the selected neighbourhoods, government officials and experts through interviews, physical observations and photographs to characterize the nature and extent of gentrification of the neighbourhoods. The planned neighbourhoods were grouped according to their densities and randomly selected one neighborhood from each stratum (high, medium and low densities). The neighbourhoods selected for the study were PH-Township (high density), Oromenike (D/Line) (medium density) and Orije layout Old GRA (low density). The second stage, the study selects 397 respondents (household heads) from the three neighbourhoods for sampling. To obtain this sample size, an average of five (5) persons per household was used to determine the household size for the study area that was selected for sampling.20,21 The sample size of 397 was derived applying Yamane formula and was distributed across the sampled neighbourhoods proportionately to cover the study area. A simple random technique was employed to choose the respondents selected for interview (Table 1). Furthermore, key informant interviews for staff of the Rivers State Ministry of Urban Development and Physical Planning, Port Harcourt City Council and other allied professionals/experts in the built environment Secondary data were collected from government Ministry, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) to profile the neighbourhoods as regard to the nature and extent of gentrification in these neighbourhoods in the municipality.22,23

Density |

Neighbourhoods sampled |

1991 population |

2019 population at 6.5% growth rate |

No. of respondents sampled/density |

High |

PH-Township |

12,369 |

72,111 |

122 |

Medium |

Orominike (D/Line) |

21,377 |

124,627 |

211 |

Low |

Orije Old GRA |

6,482 |

37,790 |

64 |

Total |

40,228 |

234,528 |

397 |

Table 1 Determination of sample size for the study

Source Fieldwork, 2019

Indications from the study evinced that the three studied neighbourhoods namely; Orije Old GRA, Oromenike (D/Line) and PH-Township are well planned out but have been characterized with attributes of gentrification. (Figure 3) show that 87% of the respondents affirmed that changes have occurred in the buildings from its original use in the municipality while 13% of the respondents said the buildings they are occupying have not change from its original use. Implicitly, there is a significant change of use of buildings within the neighbourhoods as most buildings have been altered from its common type of dwelling units of semi-detached buildings that are originally built in the neighbourhoods from (Figure 4) showing 41% of the buildings semi-detached and 21% are rooming houses and bungalows respectively. Some of the housing units have been slightly or totally altered to accommodate commercial, institutional and/or other activities either partially or totally. These gentrification characteristics span all three neighbourhoods and income groups which represented all social classes within the municipality. These alterations have succeeded in defacing the appearance of the neighbourhoods since most residential buildings are now totally or partially changed to other uses away from their designated use.

From the findings of the analysis carried out in Table 2 revealed that the buildings are old as neighbourhoods from the period the neighbourhoods were planned in the colonial period and the buildings were constructed. Most of these buildings are over 10 years old accounting for 96% and 9-10 years account for 4%. This has greatly influenced the changes occurring in the neighbourhoods as many landlords are renovating their buildings to meet the current demands for spaces of various uses. These changes were necessitated due to the need to create commercial areas within the residential areas for the purpose of income generation the landlords and to make the place attractive so as to attract wealthier people. However, some the reasons of these changes from respondents is if wealthier residents reside in an area it would reduce the probity of social vices and security challenges that residents are facing in the neighbourhoods in recent time.

S/No. |

Age of building |

No. |

% |

1 |

Less than 1 year |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1-2 years |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3-4years |

0 |

0 |

4 |

5-6years |

0 |

0 |

5 |

7-8years |

0 |

0 |

6 |

9-10years |

16 |

4 |

7 |

Over 10 years |

381 |

96 |

Total |

397 |

100 |

Table 2 Age of building

Source Fieldwork, 2019

S/No. |

Rent |

No. |

% |

1 |

₦80,000-₦119,999 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

₦120,000-₦159,999 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

₦160,000-₦199,999 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

₦200,000-₦239,999 |

20 |

5 |

5 |

₦240,000-₦279,999 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

₦280,000-₦319,999 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

₦320,000-₦359,999 |

16 |

4 |

8 |

₦320,000-₦359,999 |

67 |

17 |

9 |

₦400,000 and above |

294 |

74 |

Total |

397 |

100 |

Table 3 Rent paid for residential building annually

Source Fieldwork, 2019

S/No. |

Rent |

Shops/Offices |

% |

1 |

₦80,000-₦119,999 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

₦120,000-₦159,999 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

₦160,000-₦199,999 |

79 |

20 |

4 |

₦200,000-₦239,999 |

258 |

65 |

5 |

₦240,000 and above |

60 |

15 |

Total |

397 |

100 |

Table 4 Rent paid for space annually

Source Fieldwork, 2019

The study revealed that there are major alterations to the buildings in the neighbourhoods which have changed the landscape of the study area. The nature and extent of changes identified include remodeling of buildings, renovation of buildings covering minor repairs in the buildings such as windows, doors and roof changes. Significant changes that occurred are mostly mixed-use changes as many apartments are partly changed to commercial use such as retail outlets, offices, boutiques, restaurants and nightclubs. Other changes that have occurred in these neighbourhoods are redevelopment activities such that residential buildings are completely changed to other uses such as commercial, institutional (worship centres and educational facilities) (Figure 5,6) show that 45% respondents affirmed that the nature of change buildings were predominantly from residential to mixed use, 36% residential to shops, 15% residential to institutional while 4% was changed to other including light industrial activities such as printing press and welding and fabrication. Table 5 shows that landlords representing 48% were responsible for the change of use in the buildings in the neighbourhoods, 43% were the current occupants themselves while 9% were the previous occupants of the buildings and these approvals are gotten from the government agencies mostly the Port Harcourt City Council.

S/No. |

Person responsible for change of use |

No. |

% |

1 |

Landlord |

190 |

48 |

2 |

Previous occupant |

36 |

9 |

3 |

Current occupant |

171 |

43 |

Total |

397 |

100 |

Table 5 Person responsible for change of use

Source Fieldwork, 2019

Figure 6 Residential buildings converted to commercial use at Oromenike Layout (D/Line)

Source Researcher’s Field Survey, 2019

Some of the emergent informal squatter settlements are waterfront settlements in adjoining neighbourhoods because residents invade and occupy available open spaces within these neighbourhoods for various uses that are mostly not in line with the purpose of allocation as stipulated in the planning schemes. As part of the effects of gentrification in these neighbourhoods, there is increased vehicular and human traffic with its attendant noise pollution, increased social vices such as theft, violent crimes, prostitution and unlawful street trading. Positively, these changes have engendered some physical improvements into such neighbourhoods like aesthetics, enhanced social network, horizontal and vertical interaction amongst residents and increased economic activities as some residents tend to engage in diverse commercial activities, and increased property values for the landlords.

Gentrification as a phenomenon is an important process that shapes urban form. Port Harcourt municipality has over the years witnessed phenomenal, swift gentrification in some identified designated residential neighbourhoods within the municipality. These neighbourhoods are undergoing social and economic evolution which span through three planned neighbourhoods in the study area and covers different densities within the municipality. One of the major causes of gentrification has been identified as demand for more space for other uses away from residential uses which has instantaneously led to arbitrary surges in rent for residential accommodation. At the same time there is increased property value in these neighbourhoods because landlords tend to upgrade their aging buildings to meet up with current demand by altering the original use, shape and size without reference to the existing zoning schemes or layout plans. This trend has caused displacement of people, increased vehicular traffic and pedestrian footfalls, formation of informal settlements around the neighbourhoods and other urban social issues. To achieve a sustainable urban form with commensurate development within the municipality, there is the need for city managers and other relevant stakeholders to control this trend with the adoption a collaborative approach.

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2019 Eyenghe,, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.