MOJ

eISSN: 2574-9722

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 2

Department of the biology of organisms, University of Brussels, Belgium

Correspondence: Marie Claire Cammaerts, Department of the biology of organisms, University of Brussels, Belgium

Received: June 01, 2023 | Published: June 16, 2023

Citation: Cammaerts MC. Adverse effects of the commonly used nutmeg, studied on an ant species as a model. MOJ Biol Med. 2023;8(2):67-75. DOI: 10.15406/mojbm.2023.08.00187

The commonly used nutmeg, beneficial at low dose, appeared to have side effects at high doses. On ants used as biological models, we found that this spice affected essentially the locomotion, and also maybe consequently, the food intake, the activity, the orientation, the audacity, the brood caring, the escape behavior, but not the state of stress, the cognition, learning and memory. The ants did not adapt themselves to these side effects and developed dependence on nutmeg consumption. The effect of this spice vanished in 22 hours after weaning. All these findings are not divulgated, but must imperatively be known by users (every one, restaurateurs) and practitioners, for instance by writing them of the spice package. Nutmeg must not be no longer on authorized – it has excellent effects at low doses – its use must simply but obligatory limited.

Keywords: addiction, activity, dependence, food consumption, locomotion, operant conditioning

Mm/s, millimeter per second; ang.deg, angular degree; ang.deg./cm, angular degree per centimeter; n°, number; s, second; min, minute; mg, milligram; ml, milliliter; h or hs, hour

Nutmeg is a commonly used spice all over the world. This product has several beneficial properties at low dose, but becomes toxic at high dose. It has been shown to efficiently care of patients suffering among others from rheumatism, cholera, anxiousness, digestive impairments.1 Nutmeg has also an anti-inflammatory, an analgesic and an antithrombotic activity in rodents.2 However, at high dose, this spice present dangerous effects. It contains chemicals acting as hallucinogens, and many cases of voluntary or unvoluntary intoxications, and even deaths, has been reported. Let us cite, among others, the works of.1,3-7 People can buy nutmeg in any shop, in any wanted quantity; they must be informed about the use of this spice. Since nutmeg induces adverse effects (expected or not to have), practitioners must also be informed about the consequences of this spice use. Apart the hallucinogen and associated symptoms, nothing is reported as for the effects of nutmeg on several physiological and ethological traits. We thus aimed to fill this gap, and look at the potential impact of nutmeg on food intake, activity, audacity, sensory perception, social relationships, cognition, learning memory, as well adaptation to side effects and dependence on this spice use, on ants as biological models. Before relating our work, we here below explain why using ants as models, which species we used and what we know on it, and which trats we intended to examine.

Why using ants

Fundamental biological processes are similar for all animal species including humans (e.g., genetics, nervous influx, muscles contraction, sensory perception, conditioning acquisition). This is why they are often studied on vertebrates and invertebrates as models, and later in humans. Invertebrates are generally used for an initial study because they are small, can easily be maintained in a laboratory, and have a short reproductive cycle. Hymenoptera (e.g., bees) are often used.8 Ants can thus be used, the more so because they are eu-social, their colonies containing hundreds of individuals can be kept during months and even years, this very easily and at low cost.

Which species was used

We worked on the species Myrmica sabuleti Meirnert, 1861. We know rather well its biology, having worked on it since about forty years. Among others, we know its navigation, recruitment, visual perception,9 ontogenesis of some of their skills,10 self-recognition in a mirror,11 distance and size effects,12 Weber’s law application,13 numerosity abilities and related topics.14– 17 An ant species so well-known is, at least for us, an appreciated biological model.

Which traits was examined

The physiological and ethological traits we aimed to examine were the food intake, activity, locomotion, orientation, audacity, tactile perception, social relationships, stress, cognition, learning and memory, adaptation to side effects of nutmeg, dependence on this product use, and decrease of its effect after weaning.

Collection and maintenance of the ants

These experiments were performed on two colonies of the ant Myrmica sabuleti Meinerts, 1861 collected in simmer 2022 in the Aise Valley (Ardenne, Belgium), from a no longer exploited quarry. The two ant colonies were under stones and in grass. They contained about 600 workers, 1 or 2 queens and brood. In the laboratory, they were kept in 1 to 3 glass tubes half filled with water, with a cotton plug separating the water from the space devoted to the ants’ nesting. The nest tubes of each colony were set in a tray the borders of which having been covered with talcum. These trays were the ants’ foraging areas; food was provided in them. This food consisted in larvae of Tenebrio molitor delivered three times per week and in sugar water delivered in small cotton plugged tubes. The lighting varied between 330 and 110 lux, the humidity equaled 80% and the temperature equaled 20°, what was suitable to the used ant species. The word ‘ants’ is here often replaced by ‘workers’ or ‘nestmates’ or ‘congeners’.

Solution of muscade delivered to the ants

A commonly used by everyone glass recipient containing 30 gr of nutmeg was bought in a shop of the very well-known firm ‘Carrefour’. The adequate required amount of nutmeg was weighed thanks to a precision scale, and was dissolved in the required amount of the sugar water devoted to the ants’ feeding (see below). As for the amount of nutmeg and water to be used, humans consuming rather large quantity of this spice eat per day about 200 – 400 ml (1/3 of liter) of a water solution containing 4 – 5 gr of nutmeg, thus about 300 ml of a water solution containing 4.5 gr of the spice. They thus eat 1.5 gr of nutmeg per day. Humans drink about one liter of water per day, and those consuming rather large amounts of nutmeg consume thus 1.5 gr of nutmeg together with 1 liter of water. Due to their anatomy (cuticle) and physiology (secretory organ), the insects, so the ants, consume about 10 less water than humans. For setting the ants under a diet similar to those humans, they must be fed with a solution of 1.5 gr of nutmeg in 100 ml of water. The amount of such a solution required for feeding the ants and making the entire experimental work equaled maximally 33 ml. We thus dissolved 0.5 gr of muscade into 33 ml of the ants’ sugar water, and provided this solution to the ants in their usual small plugged tubes. It was checked several times per day if the ants drunk the delivered solution of nutmeg, and they did. The cotton plug of furnished small tubes was refreshed each two or three days, and the entire solution of nutmeg was renewed every seven days (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Realization of the solution of nutmeg given to the ants. Successively, the bought recipient of nutmeg, the sugar water solution of nutmeg, the cotton plugged tubes filled of this solution, given to the ants, and (second line) five ants drinking this solution.

Assessment of the ants physiological and ethological traits, remark

The here performed experiments and assessments were similar to those made for studying until now 66 products or situations examined as for their adverse effects on ants as models. They have thus been many times explained and are here briefly described. Readers are invited to find complementary explanations in any of previously published papers.18–21 Nevertheless, self-plagiarism was still inevitable.

Food intake, activity

For each two colonies under normal diet then under a diet with nutmeg, the ants being on the meat food, at their sugar water tube entrance, and active at any place of their environment were separately counted four times per day during six days (n = 4 x 2 x 6 = 48 counts). For each kind of count and of diet, the daily mean was established (Table 1, lines I to VI), and the six daily means obtained for ants consuming nutmeg were compared to the corresponding daily means obtained for ants under normal diet using the non-parametric test of Wilcoxon.22 In addition, the mean of the six daily means was established for each kind of diet and of count (Table 1, line I-VI).

|

Days |

Under normal diet |

Under a diet with nutmeg |

|

meat sugar water activity |

meat sugar water activity |

|

|

I |

1.63 0.63 11.75 |

0.13 0.25 2.25 |

|

II |

0.75 1.00 11.25 |

0.13 0.25 1.25 |

|

III |

0.75 1.25 11.63 |

0.13 0.37 1.25 |

|

IV |

0.75 0.63 11.50 |

0.00 0.25 1.50 |

|

V |

0.75 0.63 11.00 |

0.25 0.13 1.50 |

|

VI |

0.75 0.88 11.75 |

0.25 0.13 1.87 |

|

I-VI |

0.73 0.84 11.48 |

0.45 0.23 1.60 |

Table 1

Impact of nutmeg on the ants’ food intake and activity. The table gives the mean numbers of daily counted ants (lines I to VI), and the means of these daily counts (line I-VI). Nutmeg largely impacted these three biological traits.

Linear and angular speeds, orientation

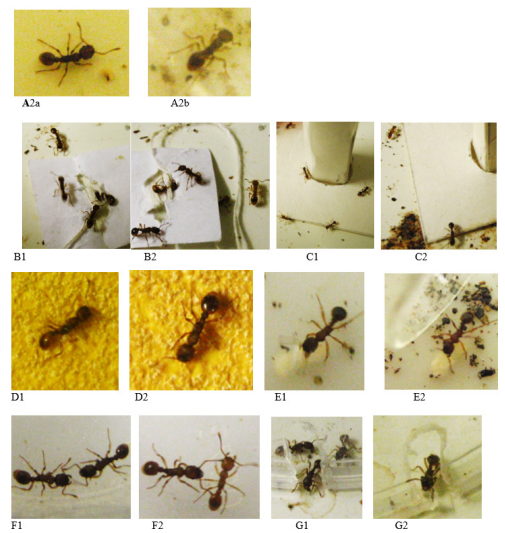

These three traits were assessed on ants walking in their foraging area, the linear and angular speeds on not stimulated ants, the orientation on ants stimulated by a nestmate tied to a piece of paper which emitted its mandible glands attractive alarm pheromone (Figure 2A&2B). For the ants’ speeds, then for their orientation, 40 trajectories were recorded and analyzed using software set up based on the following definitions. The linear speed (in millimeter per second = mm/s) was the length of a trajectory divided by the time spent to travel it; the angular speed (in angular degrees per centimeter = ang.deg./cm) was the sum of the angles made by successive adjacent segments, divided by the length of the trajectory; the orientation (in angular degrees = ang. deg.) to the tied nestmate was the sum of successive angles made by the direction of the trajectory and the direction towards the tied nestmate, divided by the number of assessed angles. A value lower than 90° means that the ant approached the nestmate. An orientation value higher than 90° means that the ant avoided the nestmate. For the three assessed traits, the median and quartiles of the 40 recorded values were established (Table 2, lines 1, 2, 3), and each time, the distribution of values obtained for ants consuming nutmeg was compared to that obtained for ants living under normal diet using the non-parametric χ² test.22

Audacity

For assessing this trait, the ants’ coming onto a cylinder (height = 4 cm; diameter = 1.5 cm, vertically tied to a squared platform of 9 cm2), both in Steinbach® white paper, set in the ants’ foraging area (Figure 2C) were counted 20 times over 10 minutes (n =20 x 2 = 40). The mean and extremes of these recorded numbers were established (Table 2, line 4). The numbers obtained for the two colonies were correspondingly added and the twenty sums were chronologically added by two, what provided ten numbers. Those obtained for ants consuming nutmeg were compared to those obtained for ants normally maintained using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test.22

|

Traits |

Under normal diet |

Under a diet with nutmeg |

|

Linear speed (mm/s) |

7.2 (6.8 – 8.0) |

2.8 (2.3 – 3.1) |

|

Angular speed (ang.deg./cm) |

103 (87 – 117) |

320 (282 – 379) |

|

Orientation (ang.deg.) |

28.6 (20.9 – 38.7) |

67.0 (50.6 – 80.7) |

|

Audacity (n°) |

1.98 [1 – 3] |

0.20 [0 – 2] |

|

Tactile perception: |

||

|

linear speed |

2.0 (1.9 – 2.4) |

2.0 (1.8 – 2.3) |

|

angular speed |

336 (283 – 383) |

324 (268 – 379) |

|

on a rough substrate |

||

Table 2

Impact of nutmeg on ants’ five biological traits. The table gives the median (and the quartiles) or the mean [and the extremes] of the recorded values. The spice largely impacted these five biological traits.

Tactile perception

This trait was estimated by assessing the ants’ locomotion on a rough substrate. Indeed, if well perceiving the rough character of a substrate, the ants walk on it slowly, sinuously, with difficulty, and often touched the substrate with their antennae (Figure 2D). For each colony, a piece (3 cm x 2 + 7 + 2 = 11 cm) of n° 280 emery paper duly folded was inserted into a tray (15 cm x 7 cm x 4.5 cm) which was so divided tray in three zones, a first 3 cm long zone, a second 3 cm long one containing the emery paper, and a last 9 cm long zone. To conduct an experiment, 25 ants were deposited in the first zone, and their linear and angular speeds were assessed while they walked on the rough substrate. For ants under normal diet and for those consuming nutmeg, the 40 values of linear and of angular speeds obtained while they walked on the rough substrate were compared to those obtained while they walked in their foraging area by using the non-parametric χ² test.22 In addition, for each kind of diet, the 40 values of linear and angular speeds obtained for ants moving on the rough substrate were characterized by their median and quartiles (Table. 2, lines 5, 6).

Figure 2 Some photos of the experiences made for examining the adverse effects of high doses of nutmeg. 1: normal diet, 2 diet with nutmeg. A: ants’ walking. B: stimulated by a tied nestmate; C: audacity; D: tactile perception; E: brood caring; F: social relationships; G: escaping behavior. See results in Tables 2, 3.

Brood caring

A few larvae of each colony were taken out of their nest and set in front of its entrance. Five of them were considered during five minutes: the workers’ behavior towards them was observed (Figure 2E) and the number of not re-entered larvae after 30 seconds, 1,2,3,4, and 5 minutes were counted (Table 3, line 1). Only five larvae per colony were considered because they must be simultaneously observed; also, the experiment was made only once because taking brood out of the nest largely perturbates the colony. The six numbers of not re-entered larvae obtained for the two colonies were correspondingly added, and the six sums obtained for ants consuming nutmeg were compared to the six ones obtained for ants normally maintained using the non-parametric test of Wilcoxon.22

Social relationships

Normally, nestmates do not aggress themselves. Some factors could affect this peaceful social behavior. For examining if nutmeg did so, five dyadic encounters were conducted for each colony (for each kind of diet: n = 5 x 2 encounters). They were made in a talked cup (diameter = 2cm, height = 1.6cm). Each time, one ant of the ants’ pair was observed during 5 minutes and its behavior was characterized by the numbers of times it did nothing (level 0 of aggressiveness), touched the other ant with its antennae (level 1), opened its mandibles (level 2), gripped and/or pulled the other ant (level 3), and tried to sting or stung the other ant (level 4) (Table 3, line 2; Figure 2F). The numbers obtained for the 10 observed ants were correspondingly added for each kind of diet, and the distribution of values obtained for ants under a nutmeg diet was compared to that obtained for ants normally fed using the non-parametric χ² test.22 Moreover, for each diet, a variable ‘a’ which equaled the number of aggressiveness levels 2 + 3 + 4 divided by the number of aggressive levels 0 + 1 was established (Table 3, line 2).

|

Traits |

Under normal diet |

Under a diet with nutmeg |

|

n° of not re-entered larvae over time |

30’’ 1’ 2’ 3’ 4 5’ |

30’’ 1’ 2’ 3’ 4’ 5’ |

|

9 8 6 2 2 0 |

10 10 8 7 5 2 |

|

|

n° of observed levels of aggressiveness, variable ‘a’ |

0 1 2 3 4 ‘a’ |

0 1 2 3 4 ‘a’ |

|

60 41 8 0 0 0.06 |

51 46 19 9 0 0.19 |

|

|

n° of ants escaped over time |

2’ 4’ 6’ 8’ 10 12’ |

2’ 4’ 6’ 8’ 10’ 12’ |

2 5 7 11 12 12 |

2 4 6 8 10 12 |

|

|

n° of ants in font (f) and beyond (b) a difficult path |

2’ 4’ 6’ 8’ 10 12’ |

2’ 4’ 6’ 8’ 10’ 12’ |

|

f: 22 22 15 14 11 10 |

f: 25 20 15 14 13 10 |

|

|

b: 0 2 2 4 5 7 |

b: 0 0 0 3 5 5 |

Table 3

Impact of nutmeg on four ants’ biological traits. The table gives the numbers of counted larvae, or levels of aggressiveness, or ants. The spice slightly impacted the ants’ brood caring, congeners’ relationships, but not their escaping behavior and twists and turns path crossing.

Stress and cognition through escaping ability

In order to escape from an enclosure, an individual must stay calm, does not stress, must look for an exit, and have its cognition not affected. For examining the impact of nutmeg on the ants’ state of stress and cognition, for ants under one and the other king of diet, six ants of each colony were inserted under a reversed talked cup (made of polyacetate; height = 8cm, bottom diameter = 7 cm, ceiling diameter = 5 cm; deposited in the foraging area), with a notch (3 mm height, 2 mm width) made in the bottom rim of the cup for allowing the ants escaping (Figure 2G). For each colony, the ants among the six enclosed ones escaped after 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 minutes were counted and the numbers obtained for the two colonies were correspondingly added (Table 3, line 3). The six sums obtained for ants under a diet with nutmeg were compared to the six sums obtained for ants normally maintained using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test.22

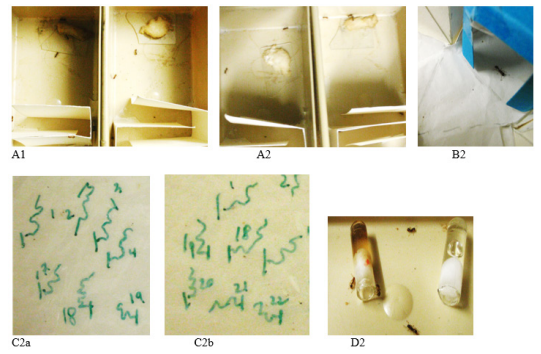

Cognition

This biological trait was evaluated thanks to the ants’ ability to cross a twists and turns path. For each colony, an adequate apparatus was constructed. It consisted in two duly folded pieces of Steinbach® paper (4.5 cm x 12 cm) inserted in a tray (15 cm x 7 cm x 4.5 cm) in order to create a twists and turns path between a 2cm long zone in front of this path and an 8 cm long zone beyond it (Figure 3A). To conduct an experiment on a colony, 15 ants were deposited into the zone located in front of the ‘difficult’ path, and the ants still there and those having reached the zone lying beyond this path were counted after 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 minutes. The numbers obtained for the two colonies were correspondingly added (Table 3, line 4), and for each zone, the six sums obtained for ants under a diet with nutmeg were compared to the six sums obtained for ants normally maintained using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test.22

Figure 3 Some views of the experiments made to study the impact of nutmeg on the ants’ cognition (A), and conditioning acquisition (B), as well as the ants’ adaptation to the effect on their locomotion (C) and their dependence on this product use (D). 1: under normal diet; 2: under a diet with nutmeg. This spice only slightly affected the ants’ cognition, and conditioning acquisition (here, an ant having given the correct response and staying motionless). The ants did not adapt themselves to the effect of nutmeg on their locomotion: a: after 1 day, b: after seven days of this spice use. The ant developed dependence on nutmeg use: they went more near the tube containing the spice (red dot) than near the free-spice one.

Conditioning acquisition, memory

At a recorded time, a blue hollow cube (in Canson® paper) was set above the entrance of the tube containing the sugar water, and the meat was transferred near this cube (Figure 3B&2a). So, the ants underwent operant visual conditioning. The experiment on ants living under normal diet had been previously made on another similar colony of M. sabuleti because when an individual has acquired conditioning to a given stimulus, it keeps its conditioning during a rather long time, and even after having lost its conditioning, it more rapidly than initially acquires it again, and can therefore no longer be used to assess its conditioning acquisition. Over the ants’ conditioning acquisition and after the blue cube removal over the ants’ loss of conditioning, the ants were tested six times in a talked Y-maze (made of strong white paper, set in a tray) having a blue hollow cube in randomly one of its branches. To make a test on a colony, 10 ants were one by one transferred in the maze, before its division into two branches, and the ants’ first choice of one or the other branch of the maze was recorded (Figure 3B&2b). Choosing the branch containing the blue cube was the correct response. After having been tested, the ant was kept in a talked cup for avoiding testing twice the same ant, and when the 10 ants of a colony were tested, all of them were set again into their foraging area. For each test, the ants’ responses obtained for the two colonies were added, and the proportion of correct responses (the conditioning score) was established (Table 4). The proportions obtained for ants under a diet with nutmeg were compared to those obtained for ants normally maintained using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test.22

|

Time (hours) |

Under normal diet |

Under a diet with nutmeg |

|

|

N°s of correct vs wrong responses given by colony A; B Score |

|

|

7 h |

60% |

6 vs 4 ; 7 vs 3 65% |

|

24 h |

60% |

6 vs 4 ; 6 vs 4 60% |

|

31 h |

70% |

7 vs 3 ; 6 vs 4 65% |

|

48 h |

70% |

7 vs 3 ; 7 vs 3 70% |

|

55 h |

80% |

7 vs 3 ; 8 vs 2 75% |

|

72 |

85% |

9 vs 1 ; 8 vs 2 85% |

|

Cue removal |

||

|

7 h |

85% |

8 vs 2 ; 9vs 1 85% |

|

24 h |

80% |

9 vs 1 ; 9 vs 1 90% |

|

31 h |

80% |

7 vs 3 ; 8 vs 2 75% |

|

48 h |

80% |

8 vs 2 ; 9vs 1 85% |

|

55 h |

80% |

7 vs 3 ; 9 vs 1 80% |

|

72 |

80% |

8 vs 2 ; 8 vs 2 80% |

Table 4

Impact of nutmeg on the ants’ conditioning acquisition and memory. The spice did not affect these important biological traits.

Adaptation to side effects of muscade

Adaptation to a product occurs when the user less and less suffers from the adverse effects of the product over time. For examining the potential adaptation to the use of nutmeg, a side effect of this product was quantified soon after the ants were under a diet with nutmeg, then later, after they were so during a longer time period, and the two assessments were compared. In the present work, the ants’ locomotion was largely affected by nutmeg, and was thus assessed after one day then after seven days the ants were under this spice diet (Figure 3C). The median and quartiles of the values obtained after seven days were established (Table. 5, upper part), and the distribution of these values was compared to that obtained after one day of diet with nutmeg using the non-parametric χ² test.22

|

Traits |

normal diet |

nutmeg for 1 day |

nutmeg for 7 days |

|

Adaption to the impact on locomotion: |

|||

|

linear speed (mm/s) |

|||

|

angular speed (ang.deg./cm) |

7.2 (6.8 – 8.0) |

2.8 (2.3 – 3.1) |

2.4 (2.0 – 2.7) |

|

103 (87 – 117) |

320 (282 – 379) |

366 (311 – 400) |

|

Dependence on nutmeg use |

Colony A Colony B total proportions |

|

N° of ants’ choice of the sugar water |

5 8 13 23.21% |

|

N° of ants’ choice of the spice solution |

16 27 43 76.78% |

Table 5

Ants’ adaptation to the impact of nutmeg on their locomotion, and they dependence on this spice consumption. The ants did not adapt themselves to the effect of nutmeg, and developed dependence on its consumption.

Dependence of nutmeg consumption

Dependence on a product occurs when the user wants to have always the product at his disposal, to consume it whatever its adverse effects, and finally to no longer live without consuming it. In this work, the ants’ dependence on nutmeg was examined after the ants had it at their disposal during eight days. For each colony, 15 ants were transferred in an own talked tray (15cm ×7 cm × 5cm) containing two cotton-plugged tubes (length = 2.5 cm, diam = 0.5 cm), one filled of sugar water, the other filled of the sugared solution of nutmeg used all over the experimental work. The tube containing the spice was set on the right in the tray of one colony and on the left in the tray of the other colony (Figure 3D2). Then, the ants present at the entrance of each tube were counted 15 times over 15 minutes, and the counted numbers obtained for each colony and kind of diet were correspondingly added (Table 5, lower part). The two sums obtained for each kind of diet allowed calculating the proportion of ants having gone to each kind of provided tube. In addition, the sums obtained for one and the other kinds of diet were compared to the numbers expected if ants randomly visited each kind of tubes using the non-parametric χ² goodness-of-fit test.22

Decrease of the effect of muscade after its consumption was stopped

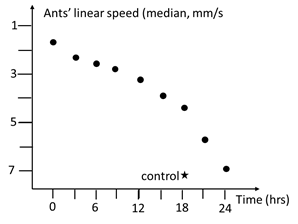

The decrease of the effect of nutmeg was studied after the ants consumed this spice for 12 days using the impact of this product on the ants’ linear speed. Twelve hours before this study, some new sugared solution of nutmeg was given to the ants, and their linear speed was assessed as it has been after they had the product at their disposal during one and seven days, except that 20 instead of 40 ants’ trajectories were recorded and analyzed, in order to be able to quantified the linear speed values successively obtained over the decrease of the effect of muscade, i.e., to evaluate the current situation. After this initial assessment (made at what we named t = 0), the ants’ tubes containing the nutmeg solution were replaced by tubes containing sugar water, and this was the start of the weaning. Since that time, the ants’ linear speed was assessed every two hours until the obtained value was similar to the control one (to that obtained for ants under normal maintenance). For each assessment, the median and quartiles of the 20 recorded values were established (Table 6) and graphically represented (Figure 4). The successively obtained distributions of linear speed values were compared to the distribution obtained at t = 0 and to the control one using the non-parametric χ² test (Table 6).22 In addition, the mathematical function best describing the observed increase of the ants’ linear speed (= the decrease of the effect of nutmeg after weaning) was tried to be defined and was written in the text.

|

Time |

Linear speed |

vs t = 0 Statistics vs control |

|

(hours) |

(mm/s) |

χ² df P χ² df P |

|

t = 0 |

1.6 (1.4 – 1.8) |

--- 59.82 1 < 0.001 |

|

3 hs |

2.2 (1.9 – 2.4) |

15.00 1 < 0.001 13.32 1 < 0. 001 |

|

6 hs |

2.4 (2.2 – 3.1) |

17.28 1 < 0.001 10.78 1 < 0.001 |

|

9 hs |

2.9 (2.6 – 3.2) |

21.60 1 < 0.001 6.32 1 < 0.02 |

|

12 hs |

3.3 (3.0 – 3.7) |

28.90 1 < 0.001 13 .81 1 < 0.001 |

|

15 hs |

4.0 (3.6 – 4.4) |

32.72 1 < 0.001 22.78 1 < 0.001 |

|

18 hs |

4.6 (4.1 – 4.9) |

32.72 1 < 0.001 10.78 1 < 0.01 |

|

21 hs |

5.9 (5.0 – 6.8) |

32.72 1 < 0.001 6.30 1 < 0.02 |

|

24 hs |

7.0 (6.6 – 8.2) |

38.72 1 < 0.001 0.62 1 < 0.50 |

|

control |

7.2 (6.8 – 8.0) |

59.82 1 < 0.001 --- |

Table 6

Decrease of the effect of nutmeg on the ants’ linear speed. The table gives the median and quartiles of the ants’ linear speed obtained over the decrease, and the results of statistical tests made versus t = 0 and the control. The effect of nutmeg became different from its initial one as soon as after about 2 hours, but stayed different of the control until about 22 hours. This decrease is illustrated in Figure 4, and detailed in the text.

Food intake, activity

Under a diet with nutmeg, the ants eat less meat, drunk less sugar water, and were far less active than while living under a normal diet. This was statistically significant (for the three examined traits: N = 6, T = -21, P = 0.016) (Table 1). Most of the ants were staying motionless in their nest and their foraging area. This was obvious to observers.

Linear and angular speeds

These physiological traits were affected by nutmeg intake (Table 2, lines 1, 2; Figure 4A). Indeed, under a nutmeg diet, the ants presented difficulties for walking: they trembled, tituped, fell down, and walked very slowly and sinuously, often stopping. This was obvious to observers and was statistically significant (for the linear as well as the angular speeds: χ² = 80.00, df = 1, P < 0.001). Such an affected locomotion could affect other behaviors, what the following experiments could check.

Figure 4 Decrease of the effect of nutmeg after weaning. The effect first soon decreased becoming different from its initial one after 3 hours, then more slowly and finally again rapidly, equaling the control in 22 hours. Numerical and statistical values are given in Table 6.

Orientation

Under a nutmeg diet, the ants did not well orient themselves towards a tied nestmate (Table 2, line3) and even went away from it, turned back on their way, a behavior we have never seen for any of the previously studied products. This was obvious for observers (Figure 2 B), and statistically significant (χ² = 40.10, df = 1, P < 0.001). This was partly explained by the ants’ difficulty to walk (see the above subsection), but could also be due to some impact of nutmeg on the ants’ audacity and sensory perception, two hypothesis the two following experiments aimed to check (see below).

Audacity

Nutmeg affected this ethological trait (Table 2, line 4; Figure C). While under normal diet, the ants came onto the provided unknown apparatus, those under the spice diet were very reluctant to do so, came back on their way when being on the apparatus or more often before climbing on it. This was obvious to observers and statistically significant (N = 10, T = -55, P = 0.001). This result was in agreement with the previous ones (see above) as well with other following ones (see below).

Tactile perception

This physiological trait was a little affected by nutmeg (Table 1, lines 5,6; Figure 2D). The ants under normal diet walked on the rough substrate with far more difficulty than on their foraging area. Their linear speed was lower and their angular speed higher, this being statistically significant (for the two speeds: χ² = 80.00, df = 1, P < 0.001). Under a nutmeg diet, the ants walked slower on the rough substrate than on their foraging area, though not so slower than when under normal diet (χ² = 14.06, df = 1, P < 0.001), but not more sinuously (χ² = 0.042, df = 1, 0.80 < P < 0.90). They thus nearly, but not exactly as on their foraging area, consequently perceiving only slightly the rough character of the substrate. This partly explained their poor orientation to a tied nestmate (see above, the ants’ orientation), and may impact other biological traits, such as their social relationships, what was examined in a following experiment Table 2.

Brood caring

Nutmeg somewhat impacted this ethological trait (Table 3, line 1; Figure 2E). Under normal diet, the ants as rapidly as they could took the larvae in their mandibles and transported them inside of the nest. While having nutmeg at their disposal, the ants had difficulties for holding the larvae, then for transporting them correctly and reaching the nest. Consequently, a significant difference appeared between the ants maintained under one and the other kinds of diet as for the numbers of not re-entered larvae over time (N = 6, T = 21, P = 0.016). This is due to the ants under nutmeg diet poor locomotion, difficulty to move, and some lower sensory perception (see above).

Social relationships

This ethological trait was slightly affected by nutmeg (Table 3, line 2; Figure F). Under normal diet, the two opponent nestmates often stayed near each other, doing nothing or making antennal contacts, seldom slightly opening their mandibles. When living under a diet with nutmeg, the ants stayed for short time periods (a few seconds) near each other, doing nothing, making antennal contacts and more often than usual rather largely opening their mandibles. Therefore, some difference emerged between the ants maintained under one and the other kinds of diet as for their behavior in front of a congener. This difference was at the limit of significance: χ² = 5.24, df = 2, P ≤ 0.05. This could be due to some impact of nutmeg on the ants’ sensory perception, as such an impact have already been suspected in previously here reported experiments (see above).

Stress and cognition through escaping ability

Nutmeg impacted this biological trait (Table 3, line 3; Figure G). Under normal diet, the ants found the exit and, then, soon went out of the enclosure. Under a diet with nutmeg, the ants moved very slowly, nevertheless, being calm, not stressing, they found the exit. In front of it, they hesitated, and took a very long time (e.g., 3 minutes) for going out the enclosure. Consequently, there was a small difference as for their escaping behavior between the ants under each two kinds of diet (N = 4, T = - 10, P = 0.063). This experiment confirmed the previously made ones (see above) and allowed expecting that the ants’ cognition could not be affected by nutmeg consumption, a presumption two reported later experiment checked.

Cognition

This biological trait was very slightly affected by nutmeg (Table 3, line 4; Figure 3A). Ants under normal diet could cross the provided twists and turns path. While having nutmeg at their disposal, they could also do so, but more slowly, hesitating, coming back on their way, progressing however correctly in the difficult path. The difference between the ants under one and the other kinds of diet as for their behavior faced to a twists and turns path was nearly not significant: numbers of ants in front of the path: N = 3, NS; beyond the path: N = 4, T = -10, P = 0;063. The ants’ cognition was thus very probably not impacted by nutmeg, as presumed in the previously here reported experiment. A following experiment (i.e., conditioning acquisition) checked again this presumption (see below) Figure 2, Table 3

Conditioning acquisition, memory

Nutmeg did not affect the ants’ conditioning acquisition (Table 4, upper part; Figure 3B2). Though the ants’ locomotion was impacted (the tested ants often stayed motionless, hesitated to move under the blue hollow cube, and walked slowly and sinuously), the ants reached a final excellent conditioning score and the difference between ants under a normal and a nutmeg diet as for their successive conditioning scores was not significant (N = 3, NS). Concerning the ants’ memory, the same events occurred. Even if walking slowly, with difficulty, the ants under a nutmeg diet kept their conditioning until at least 72 hours just like those normally maintained. The difference of behavior between the ants under one and the other kinds of diet was not significant (N = 3, NS).

Adaptation to the effect of muscade in the ants’ locomotion

The ants did not adapt themselves to the impact of nutmeg on their locomotion (Table 5, upper part; Fig?). They were even more affected after seven days than after one day on the spice diet, but this difference was not significant (linear speed: χ² =2.58, df = 1, 0.10 < P < 0.20; angular speed: χ² =2.09, df = 1, 0.10 < P < 0.20). The ants’ linear speed was thus chosen as the trait affected by nutmeg for studying the decrease of the impact of that spice after its use was stopped (see below).

Dependence on Nutmeg use

Nutmeg leaded to some slight yet significant dependence (Table 5, lower part, Figure 3D). The number of ants sighted in front of the nutmeg solution equaled 16 for colony A and 27 for colony B, while those sighted in front of the nutmeg-free solution equaled 5 for colony A and 8 for colony B. In total, ants chose 43 times the nutmeg solution and 13 times the nutmeg-free solution, what leaded to 76.78% of choices for the spice solution. The obtained numbers (43 vs 13) statistically differed from those expected if the ants randomly visited the two provided solutions (28 vs 28): χ² =7.54, df = 1, 0.001 < P < 0.01. This dependence could be explained by the excellent taste of the nutmeg sugared solution and may be by its euphoric effect, this being probably valid for humans.

Decrease of the effect of Nutmeg after its use was stopped

The numerical and statistical results are given in Table 6 and illustrated in Figure 4. The effect of nutmeg soon decreased and became different from its initial one after about 2 hours. This accounted by the development of dependence on its use (see possible explanation in the discussion section). The effect of the spice then firstly slowly and thereafter more rapidly again decreased, becoming similar to the control about 22 hours after its use was stopped (see also possible explanation in the discussion section). Note that tests made after each 3 hours were performed being blind to the previous results, and the final complex obtained decrease is perfectly valid. The curve reflecting the decrease is not exactly though nearly linear, and could be best described thanks to the following function:

Et = Et – 0.225 t

with Et = effect at time t, Ei = initial effect, t = time; E in mm/s, t: in hours

In fact, nutmeg lost 4.17 of its effect each hour Table 6.

Nutmeg is a largely used spice which has beneficial effects at low dose, but presents harmful impacts at large dose. Since nothing is reported about several biological traits impacted by this spice, we examined such potential appearances using ants as models. We found that nutmeg affected the ants’ food intake, activity, locomotion, orientation, audacity, slightly their sensory perception, social relationships; it did not impact the ants’ state of stress, cognition, learning and memory. The ants did not adapt to these side effects of nutmeg and developed dependence on its use. The effect of nutmeg vanished in about 22 hours, the initial quick decrease perceived by users accounting for the development of dependence. The results of our different experiments were in accordance with one another, as well with those of other authors (see the introduction section). They are valid, and must be known by people, practitioners, and restaurateurs. Some notes must be written on the spice package and in divulgated re-repeats.

After having finished our experimental work, looking once more at information reported on internet, we discovered some works showing the beneficial effects of low doses and harmful effects of large doses of nutmeg.

One of these papers reports that nutmeg can be used to treat stomach cramps, high blood pressure, that it stimulates the brain, is rich in fibers, vitamins and minerals, and has a lot of useful applications.23 All this is also reported in another work together with some other excellent properties such as being an antioxidant, antimicrobial and antifungal aliment. The authors precise that this is valid for low dose and that high doses of nutmeg are toxic.24 A third work once more explains the advantages of nutmeg, and mentioned its harmful effects at high dose.25 A fourth work relates in details the symptoms of a case of several impacts occurring in a patient having consumed large amount of nutmeg, and tries to explain how this could occur.26 A fifth work underlines the intoxication by high doses of nutmeg, describing the case of a patient.27

We also discovered another important work which reports that nutmeg impacts the locomotion of mice, what confirms our finding, and that this spice is active olfactory, what explains the kind of decrease we found: a first quick one due to the volatiles of the spice, a later one due to its ingested compounds.28 Note that ants appeared to be good models for making such kinds of studies at low cost, and not long lasting.

The commonly used spice nutmeg is beneficial at low doses, but harmful at high doses, impacting several important biological traits, though not the state of stress, cognition, learning and memory. It induces dependence, and its effect vanishes in 22 hours. All this is not divulgated, but must be known by users and practitioners, must be for instance written on the spice packages for avoiding involuntary or voluntary use of high doses. Nutmeg must not be withdrawn since low doses are excellent for food taste and the health, but precautions must be taken to avoid health accidents occurring with high doses.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2023 Cammaerts. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.