MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2935

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

1Al Amal Complex for Mental Health Dammam Saudi Arabia

2Department of Psychology Anglia Ruskin University United Kingdom

3Consultant Clinical Health Psychologist Neuroscience Institute Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Ahmed Alkhalaf, Consultant Clinical Health Psychologist, Clinical Psychology Unit, Psychiatry& Mental Health Services , Neuroscience Institute, Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare, Dhahran 31311, Saudi Arabia

Received: February 21, 2018 | Published: February 7, 2019

Citation: Alahmari T, Ashworth F, Alkhalaf A. Changing trends of substance addiction in Saudi Arabia between 1993 and 2013. MOJ Addict Med Ther. 2019;6(1):39-47. DOI: 10.15406/mojamt.2019.06.00145

Background: Prevalence rates of substance dependency in Saudi Arabia have risen over the last twenty years. Although there is substantial research on alcohol and substance abuse in the Arab region, only a few papers give detailed review of the rising concern

Aim: The present study aimed at comparing data of admitted hospital cases between 1993 and 2013. It was expected that changes will be observed in substance abuse and dependence in hospital admissions between 1993 and 2013. It was also expected that these changes will be associated to certain demographics and frequency of admissions.

Method: Records from a total of 2,048 admitted cases were obtained from the Al Amal Hospital of Dammam. Type of addiction, demographics, frequency of hospital admissions and number of substances abused were compared between 1993 and 2013.

Findings: The data was subjected to quantitative analysis and findings showed significant differences in type of addiction and sociodemographics between 1993 and 2013.

Conclusion: These changing trends suggest that there is a growing need to review data in order to implement new strategies, policies and interventions for positive outcomes in populations affected by substance addiction.

Keywords: substance addiction, changing trends, epidemiological studies, alcohol, drug abuse, psychiatric

The prevalence of addiction has changed drastically in the last decade in the Arabian Gulf and a number of studies are attempting to grasp its magnitude in order to make services more accessible to individuals with addictions.1 In Islamic countries, where alcohol and drug use are legally forbidden, the stigmatization of addiction can make epidemiological studies far more challenging.2 Research on addiction in Arab countries began in the early 1980s. Between 1981 and 1982, there was a 50% increase in admissions for alcohol and drug abuse in Kuwait hospitals, of which 11% were psychiatric.3 Recent empirical evidence, indicates that the prevalence of substance abuse is rising.1,4,5 This is evident by the growing number of treatment centers for drug and alcohol abuse such as “Al-Amal” hospitals in Saudi Arabia.6 A number of factors may have changed in Saudi Arabia to cause the rise in substance abuse prevalence rates over the last 20 years.3,4,6 The aim of the current study was to explore the links between addiction prevalence in Saudi Arabia, diagnosis, age, employment status, relapse, and criminal history.

A number of studies have indicated that there is an increasing prevalence in substance abuse in Arabic countries. 1,2,7,8,9 The typical profile of a substance abuser is the young unemployed male of low educational status.6,10 A few early studies conducted in Saudi Arabia reported that the mean age of substance abusers was 29 years with those who abuse heroin being younger than those who abuse only alcohol.3,4,6,11,12 A few studies have also reported low prevalence rates among women13–15 which may be due to specific treatment protocols currently utilized for females. For example, in Kuwait women are treated either in general psychiatric units or prisons,13 not in specialized rehabilitation centers. However, the stigma attached to substance use and fear of disclosure often makes it challenging for researchers to obtain data from men, let alone from Arab women.1 Although there is substantial research on alcohol and substance abuse in the Arab region, only a few papers give a detailed review of the rising concern.1,5,16 Specifically, the authors of an early study7 argued that the problem of drug abuse in Arab countries is multi-dimensional and treating the problem is rather challenging as there is currently no program in the region that can be universally efficient in reducing drug dependence. In their review,7 the acknowledge the fact that both criminalization and decriminalization have no apparent effect in reducing addiction. Similarly, another study1 emphasized the complexity of treating addiction in Arab countries and the challenges to research due to stigma and fear of disclosure imposed either by the culture or the law. A 10-year review17 of 591 patients who had been admitted to a drug rehabilitation center showed that all admitted cases were males between 16 and 66 years of age, 42% were married, 60% were unemployed, 51% were educated below secondary school level, 77% had been admitted voluntarily, and 23% were brought to the clinic by family members. In addition, 41% were admitted due to alcohol problems, 20% for prescription drugs, and 16% for heroin use. Other researchers18 have stressed the importance of more research on substance abuse in Arab countries, as currently the majority of research employs measurements that have been developed and validated either in the United States or Europe. Establishing a non-Western journal is of paramount importance for validating effectively appropriate interventions in the Arab region without having to rely on measurements and prevention programs imported from the West.18 The prevalence rates are different for each drug and for certain socio-demographic variables.2 For example, 30% of first admission patients are from families with a history of alcohol abuse and 16% are from families with a history of drug abuse.17 In addition, the main reported substance of abuse is alcohol (41.3%). Drugs such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and inhalants are reported by 22.5% of patients, and heroin is reported by 16.3%. The remaining drugs include prescription drugs, such as pain killers including tramadol, methadone, and codeine; sedatives including Xanax and valium; and other psychoactive substances including kemadrine, artane, and khat. Since 2009, there has been a drastic increase in the use of prescription drugs and abuse of psychoactive polysubstances other than alcohol, heroin, and THC.17 In the decade from 1986 to 1996, there was a 25% increase in the mean number of drugs abused per individual.2 There was also a shift from alcohol as the sole substance of abuse to amphetamine-type stimulants in the form of fenethylline (captagon), with increasing numbers of instances of confiscations by enforcement authorities being reported by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The number of patients admitted for addiction treatment in Kuwait rose from 386 in 1997 to 779 in 1999.14

AbuMadini and colleagues2 reviewed the records of 12,743 patients who were admitted to a specialized addiction unit in Saudi Arabia between 1986 and 2006. In the first decade, the majority (83%) were aged 20-39 years, never married (60%), and with low educational status (81%). In the second decade, subjects were significantly older and had a higher rate of employment than in the first decade (28.9 years versus 30.2 years; 27% versus 19%). The mean annual inception number (AIN) rose from 509 in the first decade to 765 in the second decade. In the same periods, the relative frequency of substances (RFS) increased for amphetamines and cannabis (from 12.1% and 17.5% to 48.1% and 46.5%, respectively), decreased for heroin, sedatives, and volatile substances (from 51.1%, 15.1%, and 6.1% to 22.5%, 7.3%, and 2.5%, respectively), and remained stable for alcohol (27.1% and 26.7%). These findings show that over the past 20 years there has been a shift in the socio-demographic factors that relate to addiction in Saudi Arabia. One possible explanation of the changes in socio-demographics is that younger users have now become older and addicted to other substances such as heroin14,15,19 or prescription medications.13,20 Evidence from research in Saudi Arabia shows that addiction is related to a number of other factors, such as age,2 marital status, employment status, mental health 1,3,7,21, 22 level of education, and occupation.5,6,10,11,23–26 It may be that these trends have changed as more men are now unmarried and unemployment rates in Saudi Arabia have risen over the last 10 years. 27–30 Older age for example has now been found to be correlated with the use of harder drugs.8,31 With regard to occupation, evidence suggests that in the Arabian Gulf many drug addicts are unemployed. For example,17 found that 60% of patients were unemployed and 33% were either employed or students. Similar levels of unemployment have also been reported by other authors.2 Moreover, AbuMadini and colleagues (2008) also stated that 80.8% of users had completed less than a secondary education, a rate similar to the figures17 reported about socio-demographics of substance abusers in the Arabian Gulf, as 51% did not have a secondary education, 33% had secondary education, and 16% had a post-secondary education. Other research evidence also suggests strong correlations between low educational status and rise in addiction in both the Arabian Gulf and Saudi Arabia.11,17,23 found that heroin and other drugs were the preferred choices for younger patients aged 16 to 26 years, but alcohol was favoured among those aged 37 to 66 years. Polysubstance use (abuse of three or more substances simultaneously) has steadily increased over time with a drastic increase since 2009.17 Furthermore, evidence suggests that this pattern is also prevalent in Saudi Arabia, where 57.1% of all patients were young adults under the age of 30 and 77.8% were younger than 40 years.2 Thus, not just younger addicts but also those that are older are taking drugs. This shows how the age of onset of substance abuse has also changed over time, as initially primarily younger patients were taking drugs.2 Perceptions about who uses drugs are also inaccurate. For example, a study of medical students’ beliefs about substance misuse revealed that 75% believed that alcohol use and substance abuse is a real problem in the Saudi community, but the majority believed that substance abuse is primarily a problem for young males aged 15 to 30 years, and approximately one-third of the medical students indicated they believed that use of alcohol and other substances could have some beneficial effect in the form of alleviation of stress.32 Relatedly, the majority of the medical students perceived alcohol to be the most commonly abused drug in the community, followed by amphetamines, heroin, cannabis, and cocaine. Participants also believed that friends’ influence is the most important predisposing factor leading to abuse of alcohol and other substances, followed by life stressors, tobacco smoking, and curiosity related to experimentation. Of those factors considered, the factors medical student participants believed contribute least to substance abuse were physical illnesses and inadequate recreational facilities.32

Aims and objectives

The evidence presented above shows there is a gap in knowledge of the current trends of alcohol and substance addiction in Saudi Arabia, as most studies were conducted in the 1980s and 1990s and captured only a glimpse of the picture by looking at abuse at one point in time. There have been longitudinal studies in the area, but to date even the longitudinal studies examined relatively short time periods. The present study aimed to add to the data available and provide a more accurate picture of the longer-term trends in Saudi Arabia. Specifically, this study aimed to look at changing trends in substance addiction in Saudi Arabia over the last 20 years by comparing data from two points in time 20 years apart. In order to meet the above objectives, secondary data were obtained from Al Amal Hospital in Damman in Saudi Arabia and a systematic analysis was used to compare factors (e.g., criminal record, educational status, social status, relapse rates, number of substances abused) associated with substance abuse of admitted patients between 1993 and 2013. In addition, the study also aimed to look at the inter correlations between different types of substances. For example, which substances are more likely to be abused together? If there are factors that differ between recent years and approximately 20 years ago, then treatment programs must be adjusted to better suit the needs of the patients. The present study aimed to investigate the following questions: Are there changes between 1993 and 2013 in terms of the factors associated with substance abuse? What are the most significant factors associated with substance abuse in 2013?

Design

The variables examined in this study were substance(s) of addiction (alcohol, opium, cannabis, hypnotics/sedatives, stimulants, and volatile solvents), demographics (age, criminal history, educational level, employment, and social status), number of admissions, and number of substances abused.

Materials

Medical records were obtained from the Al Amal Hospital in Damman in Saudi Arabia. Each admitted case was assigned a record number that included information on relapse frequency (number of admissions), number and types of substances abused (alcohol, opioids, cannabis, sedatives/hypnotics, volatile solvents, and stimulants), criminal record (yes or no), social status, educational status, and age.

Procedure and ethics

The first author was granted permission from the authorities of Al Amal Hospital in Damman, where he is currently employed, to have access to data files of two cohorts (all admitted cases from 1993 and all admitted cases from 2013). The current study was also ethically approved by the psychology department of Anglia Ruskin University and complied with the ethical guidelines dictated by the British Psychological Society.

Participants

Records from a total of 2,048 admitted cases (720 from 1993 and 1,328 from 2013) were obtained from the Al Amal Hospital of Dammam in Saudi Arabia. The minimum age of all admitted cases in 1993 was 15 and the maximum age was 62 (M=29, SD=7.19). The minimum age of all admitted cases in 2013 was 17 and the maximum age 70 (M=33, SD=9.39).

Analysis

Chi-square was used to test for associations between types of substance abuse/dependence separately, between demographics and types of substance abuse/dependence, and between number of admissions and substance abuse/dependence separately in data sets from both 1993 and 2013. Findings were compared across the two cohorts (1993 and 2013) and all data was subjected to post hoc analysis by checking the standardized residuals.

Main differences in addiction between 1993 and 2013 (Table 1)

|

1993 (n=720) |

2013 (n=1364) |

Criminal record |

29.90% |

27.30% |

Number of substances abused |

71.60% |

70.70% |

Educational status |

97.1% no education |

33.9% higher education |

Unemployment |

63.80% |

59.50% |

Relationship status |

56.5% single |

62.9% single |

|

36.4% married |

31.7% married |

Table 1 Demographic characteristic in the admitted cases between 1993 and 2013

Number of substances abused and substance addiction

Table 2 shows the significant associations between number of substances abused and addiction for all cases admitted in 1993 and 2013 respectively. Empty columns indicate no significant post hoc associations. In the admitted cases from 1993, no significant associations were found for stimulants, Fisher exact test (N=703), p=.46, or volatile solvents, Fisher exact test (N=703), p=.29.

1993 |

1(N=503) |

2 (N=152) |

3 (N=37) |

Alcohol |

A 42% |

A 7% |

A 26.3% |

Fisher exact test (N=703): p=.00, |

|||

Cramer’s V=.20 |

|||

Opium |

NA 44.3% |

D 80.9% |

D94.6% |

Fisher exact test (N=703): p=.00, Cramer’s V=.24 |

D48.7% |

||

Cannabis |

NA 97.2% |

D 15.1% |

A 35.1%, |

Fisher exact test (N=703): p=.00, Cramer’s V=.44 |

D48.6%, |

||

Sedatives/hypnotics |

NA 96.8% |

NA54.6% |

NA24.3% |

Fisher exact test (N=703): p=.00, Cramer’s V=.45 |

A 7.2%) |

A13.5% |

|

D 38.2%, |

D62.2% |

||

2003 |

1st time(N=359) |

2nd time (N=495) |

3rd time (N=403) |

Alcohol |

NA 89.7% |

A16.2% |

A67.7% |

χ² (5, N=1270)=543.01, p<.001, |

D14.9% |

||

Cramer’s V=.46 |

|||

Opium |

D 53.8% |

||

Fisher exact test (N=1270): p=.01, Cramer’s V=.08 |

|||

Cannabis |

NA 82.5% |

AD29.1% |

A 37.2%, |

Fisher exact test (N=1270): p=.01, Cramer’s V=.46 |

A1.4%, |

D 44.3% |

D57.8% |

D16.2% |

|||

Sedatives/hypnotics |

NA 98.9% |

A 15.9%, |

|

Fisher exact test (N=1270): p=.01, Cramer’s V=.21 |

|||

Stimulants |

NA 55.4% |

A9.5% |

AD18.1% |

Fisher exact test (N=1270): p=.00, Cramer’s V=.28 |

D 44% |

A26.8% |

|

Volatile solvents |

D 7.7%, |

||

Fisher exact test (N=1270): p=.00, Cramer’s V=.12 |

|

|

|

Table 2 Significant associations between number of other substances abused and substance addiction

AD, addiction; A, abuse; NA, no addiction; D, dependence

Age and addiction

As can be seen in Figure 1, in 1993 individuals in younger age groups were more likely to be dependent on opioids and opium, whereas in 2013 (Figure 2) older age was associated with opioids and opium dependence. In 1993 a significant association between age and addiction to opioids and opium was found, Fisher exact test (N=677), p=.00; Cramer’s V=.16. Post hoc analysis showed that the standardised residual (SR) for opium abuse in the age group 15-25 (n=177) was -2.0, which indicates that there were fewer cases in this age group that were abusing opioids and opium (1.7%). In the age group 26-35 (n=392) there were significantly fewer cases (30.9%) with no addiction to opioids and opium (SR=-2.5). In the age group 46-55 (n=19) there were significantly more cases (78.9%, SR=2.8) with no addiction to opioids and opium and significantly fewer cases that were dependent on opioids and opium (15.8%, SR=-2.4). In 2013, there was also a significant association between age and opioids and opium abuse, Fisher exact test, p=.00, Cramer’s V=.26. Post hoc analysis showed that there were significantly more cases (90.6%) in the age group of 15-25 (n=320) that were not addicted to opioids and opium (SR=2.3) and significantly fewer cases (9.4%) that were dependant on opioids and opium (SR=-4.5). In the age group 26-35 (n=579) there were significantly more cases (88.1%) that were abusing opioids and opium (SR=2.5) but significantly fewer cases (11.9%) that were dependant on opioids and opium (SR=-4.7). In the age group 36-45 (n=283) there were significantly more cases (66.8%) with no addiction to opioids and opium (SR=-2.3) and significantly more cases (33.9%) with opioids and opium dependence (SR=4.4). In the age group of 45-56 (n=153) there were significantly more cases (48.4%) who were not addicted to opioids and opium (SR=-4.3) and this was significantly different from those who were dependant on opioids and opium (51.6%, SR=8.3). Finally, in the age group 56 and over (n=19) there were significantly more cases (n=7) who were not addicted to opioids and opium (SR=-2.1) and significantly more cases (n=12) that were dependant on opioids and opium (SR=4.0) (Figure 1& Figure 2).

Criminal record and addiction

In 1993 criminal record was not associated with alcohol, opium, or stimulant addiction, whereas in 2013 it was associated with all three. Figure 3–5 shows the findings for 2013 for different substances.

Educational level and addiction

In 1993 educational level was not associated with alcohol, opium, cannabis, or stimulant addiction, whereas in 2013 it associated with some of these substance addictions. Figure 6–9 show the associations between educational level and addiction to different substances. Lower education levels were associated with alcohol dependence. In the 2013 sample, the higher the education level, the more likely abuse of and dependence on cannabis and stimulants was observed.

Employment status and addiction

In 1993 employment status was not associated with addiction to opium and stimulants, whereas in 2013 it was. Figure 10 & Figure 11 show the associations between employment status and alcohol addiction and addiction to stimulants in the admitted cases from 2013. Both unemployment and employment were associated with stimulant dependence.

Number of admissions (relapse)

In 1993 number of admissions (relapse) was not associated with addiction to stimulants, whereas in 2013 it was. Figure 12 shows the association between relapse and addiction to opium in the admitted cases from 2013. As can be seen and according to the post hoc analysis, dependence on stimulants was associated with increased number of admissions.

Figure 12 Associations between number of admissions and opium addiction in the admitted cases of 2013.

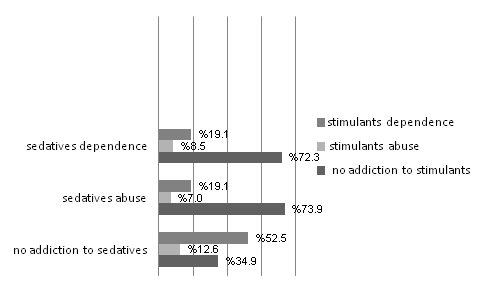

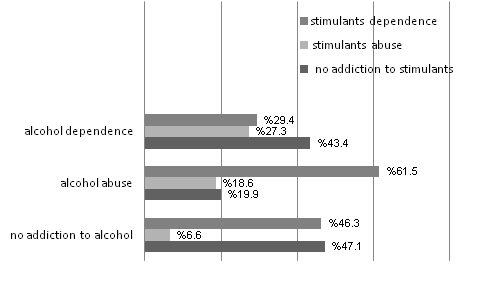

Types of substances abused

In 1993 there was no significant association between alcohol addiction and stimulant addiction, between opium addiction and cannabis addiction, or between sedatives/hypnotics addiction and stimulant addiction. However, there were associations among these addictions in 2013. Figure 13–15 shows the significant associations. Those who were abusing and dependent on alcohol were also abusing and were dependent on stimulants. The greater abuse and dependence on opium, the lower the likelihood of cannabis abuse and dependence. Those patients who were dependent on sedatives were less likely to have an addiction to stimulants.

Figure 13 Association between alcohol addiction and stimulants addiction in the admitted cases of 2013.

Figure 16 shows the factors associated with substance dependence in 2013. The factors associated with stimulant dependence are alcohol abuse, first time admission, and criminal record. The factors associated with opium dependence are being unmarried/single, cannabis abuse, unemployment, and being aged 45 or older. Single status was also associated with all other substance dependence except for volatile solvents dependence/abuse.

Findings revealed that certain demographics, such as age, criminal record, educational, social, employment status, and relapse were all associated to different extents with substance addiction between the two waves. The main differences in factors associated with addiction comparing years 1993 and 2013 were age, criminal record, educational level, employment status, relapse, and type of substance abused.

Changing trends

With regard to age, the findings of the present study showed a changing trend in addiction to opium such that younger age groups were more likely to be dependent on opium in 1993, and older age was associated with addiction to opium in 2013. Previous research3,6,12 has also reported that heroin users in the 1990s were frequently younger than individuals who abused alcohol. In addition,26 found that only 1.7% of over 25,000 cases admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Saudi Arabia were addicted to alcohol. On the other hand,32 argued that geographical position in terms of proximity to countries that produce opium has resulted in an increase of opium abuse among young populations in Saudi Arabia in the 2000s. In addition, Iqbal25 reported that heroin, alcohol, hashish, opium, barbiturate, benzodiazepine, amphetamine, and khat were the most common drugs abused among youth in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, opium and alcohol dependence was rather prominent in 1993 among older patients, but in 2013 opium and alcohol abuse were more prominent among younger patients.

A change was also observed in the relationship of criminal record to alcohol and substance abuse. In 1993 criminal record was not associated with alcohol, opium, or stimulant addiction, but by 2013 criminal record was significantly associated with abuse of the substances. Among those admitted patients with criminal records, a substantial proportion was abusing alcohol. Therefore, criminal record has become associated with alcohol abuse. Individuals with a history of opium abuse and addiction did not generally hold criminal records. Criminal records were associated with addiction to stimulants. Findings showed that there were significantly more cases of addiction to stimulants among those with criminal records, suggesting that criminal record is associated with addiction to stimulants. Perhaps the low rate of addiction to strong drugs could be attributed to the fact that criminal record is usually associated with alcohol addiction and softer drugs such as cannabis. However, a link between having a criminal record and substance addiction does not necessarily mean that it is the crime that attracts addiction. The law in Saudi Arabia punishes with imprisonment those who use or possess illegal drugs, therefore criminalization may be a consequence of drug use.1,2,7 Iqbal25 found that 50.76% of inpatients on a detox unit in Saudi Arabia were alcohol dependent.

In 1993 educational level was not associated with alcohol, opium, cannabis, or stimulant addiction, but it was in 2013. Among those patients with only a basic level of education, a substantial proportion was dependent on alcohol. A substantial proportion of those patients with a higher level of education were also abusing alcohol. Findings also revealed associations between opium addiction and educational level. Among substance abuse cases with no education, a substantial proportion was dependent on opium, whereas among those with higher education, the majority were not addicted to opium. Therefore, the higher education the patient has, the less likely to abuse and be dependent on opium. Associations were also found between educational level and cannabis addiction in the admitted cases from 2013. Among those patients with higher education levels, a substantial proportion was dependent on cannabis. Among those with secondary education, the majority were abusing and dependent on cannabis. Therefore, among the patients, the higher the educational level, the more likely the abuse and dependence on cannabis. Educational level was also associated with stimulant addiction in admitted cases from 2103. Among those of higher education, the majority were dependent on stimulants. Past research evidence also suggests that limited education is one of the most common socio-demographic variables associated with substance dependence.6,10

As for employment status, in 1993 employment status was not associated with addiction to opium and stimulants, whereas in 2013 unemployment was associated with opium use among those who went on to be admitted for treatment of substance abuse. Among unemployed patients, a substantial proportion was dependent on opium, but only a small proportion of patients who had been employed were dependent on opium. Other evidence also suggests that in the Arab Gulf many drug addicts in treatment facilities are unemployed. In a 2013 study, Elkashef found that 60% of substance abuse patients were unemployed. The relationship between substance addiction and unemployment is also reported by AbuMadini et al.8 Similar findings were obtained elsewhere 13 years earlier, as unemployment was a typical characteristic of a Saudi Arabian substance user.10 In the current study, among the unemployed a substantial proportion was dependent on stimulants and among the employed the majority were dependent. Therefore, both people who were unemployed and people who were employed exhibited stimulants dependence.

Findings showed that in 1993, dependence on opium and volatile solvents was associated with being single. In 2013, being single was associated with alcohol abuse, cannabis abuse, and sedatives/hypnotics dependence. Being divorced was most strongly associated with opium and cannabis dependence and least associated with stimulants addiction. These findings are in line with evidence suggesting that substance abuse is more common in unmarried and unemployed men in Saudi Arabia.27,29,30 The previously mentioned study from AbuMadini and colleagues2 in which they reviewed records from 12,743 patients who were admitted to a specialized addiction unit in Saudi Arabia between 1986 and 2006 is perhaps the best prior example of changing trends in addiction. In the current study, in the first sample (from 1993) the majority of cases never married (60%) and had low educational status (81%). In the second sample (from 2013), the relative frequency of abuse increased for amphetamines and cannabis and decreased for heroin, sedatives, and volatile substances, but figures remained stable for alcohol abuse. Amir19 also found that single older men were more likely to also be heroin users. This is consistent with the findings of the current study, as one would expect divorced individuals who use heroin to be of a relative older age.

A change was also observed in relation to relapse. In 1993 number of admissions (relapse) was not associated with addiction to stimulants, whereas in 2013 it was. Dependence on stimulants seemed to be associated with increased number of admissions. Previous research24 also supports these findings. In his study of relapse among substance abuse patients in Riyadh,24 found that the longest duration of abuse was for alcohol and sedatives, with heroin abusers representing a small proportion of long-term abusers. In 2013, first time admissions were associated with opium dependence. Second time admissions were associated with opium dependence and abuse of cannabis, sedatives/hypnotics, and stimulants. Opium dependence was associated with third and fourth time admissions. This increase in prevalence rates of heroin abuse has also been reported elsewhere, where it was found that heroin was becoming the preferred choice for young adults in Arab Countries.17 Others32 also found that the most common drugs of abuse in the Arab community were amphetamines, heroin, cannabis, and cocaine.

In 1993, those who abused more than two substances were most likely to abuse alcohol and be dependent on opium, sedatives/hypnotics, and cannabis. This finding is in line with studies undertaken in the 1990s11,14 which showed that heroin, cannabis/hashish, and alcohol were the most prominent substances abused. However, in 2013 those who were abusing at least two substances were most likely not addicted to alcohol, but rather were likely dependent on cannabis, and those who were abusing more than two substances were abusing alcohol and dependent on opium, sedatives/hypnotics, cannabis, stimulants, and volatile solvents. The findings from 2013 showed that polysubstance abuse was more prevalent than what it was in 1993. Previous research from25 reported that 87% of cases who were admitted to a detox unit in Saudi Arabia were using opium and 86% were addicted to a single drug. In another study conducted in a detox unit in Saudi Arabia, Iqbal25reported that 50% of those abusing alcohol were dependent on arak (an alcoholic beverage made of grapes and aniseed), 26% abused eau de cologne, and 23% abused both. With regard to sedatives, stimulants, and volatile solvents, other studies also have shown that the most commonly abused substances in Arab countries are alcohol, heroin, and hashish25,32 along with barbiturates, benzodiazepines, amphetamines, cocaine, khat, and solvents.6,13,14,19 Results of the present study also revealed novel findings with regard to correlations between different types of substances abused. In 1993 alcohol addiction and addiction to stimulants was not associated, but in 2013 they were. Previous research in the early 1990s found that alcohol-dependent individuals were often identified as single users, whereas opium-dependent individuals were often reported to be polysubstance abusers.12 Recent figures also confirm this shift from alcohol as the sole substance of abuse.2,17 In other words, polysubstance abuse is a more common phenomenon than it was two decades ago. Those who abuse and are dependent on alcohol are now more likely to also be abusing and dependent on stimulants as well.

Similarly, in 1993 opium addiction and addiction to cannabis were not associated, but in 2013 the two are actually negatively associated. Findings showed that the greater the abuse and dependence on opium, the lower the likelihood of cannabis abuse and dependence. It is worth mentioning that hashish and opium were traditionally used for medicinal purposes in most Arab Gulf countries,7 and the rise of cannabis and opium could be attributed to a resurgence of this tradition. The gateway relationship between cannabis and illicit drugs such as heroin is also well-established in the West.33–37

In 1993 addiction to sedatives/hypnotics and addiction to stimulants were not associated, whereas in 2013 the two were negatively associated. That is, patients in 2013 who were dependent on sedatives were less likely to have an addiction to stimulants. These findings are consistent with the idea that some drugs are more likely and less likely to be abused together. Sedatives induce a different effect than stimulants do. It is expected that those who abuse sedatives are less likely to abuse stimulants and vice versa. However, the finding could also be due to recent figures that show a decrease in sedatives abuse in Arab countries in general.2

Limitations

Although the present study offered valuable insights into the factors associated with and trends in substance addiction in Saudi Arabia, certain limitations need to be addressed. The present study used secondary data. Although analysis of medical records can offer information about patterns of addiction, the use of primary data (i.e., collecting data from participants through questionnaires) may have yielded more insight into causal relationships between different factors and addiction. The present study compared medical data from two points in time that were 20 years apart in order to examine whether patterns have radically changed in the intervening 20 years. However, the admitted cases in 1993 were comparatively fewer than the admitted cases in 2013, making some of the observations inconclusive. Future research could look at the relationship between addiction and psychiatric disorders such as depression and schizophrenia. Although the present study used a variety of socio-demographic data, no information was available about socioeconomic status, family history of addiction, or co-morbid disorders. As addiction appears to be multidimensional and multifactorial, health care organizations in Saud Arabia may benefit from using an updated record keeping system that includes more detail about each admitted case. Finally, the reported figures regarding drug addiction, specifically with respect to criminal history and relapse, may not be accurate given that imprisonment is also a possibility. Substance-dependent individuals with criminal records may be in prison rather than treatment facilities, make the observed relationships between various substances and having/not having a criminal record in the patients in this sample potential non-representative of the larger population of substance-dependent or abusing individuals.38–40

The findings of the present study showed that there were changes between 1993 and 2013 in terms of the factors associated with substance abuse. The main factors associated with substance dependence in 2013 were criminal record, first time admission, unemployment, being single, alcohol and cannabis abuse, being middle aged (for opium dependence), and being a youth (for cannabis and stimulants abuse). Furthermore, factors associated with stimulant dependence were alcohol abuse, first time admission, and criminal record. Factors that were associated with opium dependence were single status, cannabis abuse, unemployment, and being aged 45 or older. Single status was also associated with abuse of all other substances except volatile solvents. These changing trends suggest that there is a growing need to review data in order to implement new strategies, policies, and interventions for positive outcomes in populations affected by substance addiction. The findings of the present study also have clinical implications for education, preventive health, tailored treatment programs and other related programs specifically designed for getting people back to work and successfully integrating people back into society.

We are pleased to submit our manuscript entitled: “Changing trends of substance addiction in Saudi Arabia between 1993 and 2013”. My co-authors and I are excited about the opportunity to submit for your consideration the research presented in the enclosed manuscript, “Changing trends of substance addiction between 1993 and 2013: A comparative study of medical records in a rehabilitation centre in Saudi Arabia”. Our manuscript sheds light on the shifts in substance abuse and addiction in a Muslim country at an important time in history, as the world is becoming increasingly globalized and cultures have more contact and interconnection. As an international journal focused on licit and illicit drug use, we believe MOJ Addiction Medicine & Therapy is particularly well-suited for this manuscript.

Looking at hospital admissions from 1993 to 2013, we found significant differences in the substances being abused and in sociodemographics of the individuals diagnosed with drug addictions. The findings suggest that policy makers will need to consider addiction-related trends when implementing strategies and laws intended to improve public health in Saudi Arabia. This manuscript has not been published nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere. Thank you for your consideration of our work for publication in MOJ Addiction Medicine & Therapy.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Alahmari, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.