MOJ

eISSN: 2576-4519

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 1

1Faculdade Venda Nova do Imigrante, Brazil

2Centro Universitario UNA, Brazil

Correspondence: Rafael Souza da Silva, Faculdade Venda Nova do Imigrante, Brazil, Tel +5531986402777

Received: June 07, 2023 | Published: July 14, 2023

Citation: da Silva RS, Gallegos RAP. The artistic and temporal representations of the tarot and social relationships through the crazy arcanum. MOJ App Bio Biomech. 2023;7(1):113-119. DOI: 10.15406/mojabb.2023.07.00183

The present work aims to understand the intrinsic connection between the Tarot card game, based mainly on its temporal artistic representations, and the relations of the social game. Starting from the point of iconographic and iconological research of the arcanum The Fool, we sought to correlate it with some historical clippings of Western society, in order to interpret it as an archetype and semiotic element within its archetypal perceptions and the actions of the human being in society. The aim was, then, to understand human narratives over the centuries through the prism of artistic representations of this game shrouded in mysteries as to its origin and its great – although contradictorily discreet – presence in different cultures and spiritual and analytical segments.

Keywords: tarot, art, semiotics, archetype, history

Symbolism has been present in human life since the dawn of humanity's first artistic manifestations. Cave paintings are evidence of how representation, symbol and figure are primary and natural expressions of human life. The Tarot, of almost unknown origin, became a widespread deck in Europe in the medieval period.

Composed of a sequence of symbols, with individual and collective meanings, the game can be understood both as a tool that is currently widespread in esoteric and spiritual circles, and as a set of iconographies that respond to each card's own iconology.

This Tarot observation is related to Charles Sanders Peirce's1 studies on semiotics, in which the symbol can become universal, responding to a social and collective position, but starting from the individual as the unit that makes up this whole. Throughout research on artistic representations of the Tarot, and the influence of historical perspectives on its conceptions and uses, it was also observed the strong conception of archetype within the considerations of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung and in the studies of Sally Nichols.2

The archetypes in Jung can be understood as a sequence of phenomena, which correspond to universal feelings and experiences, similarly existing throughout much of the world. It is something almost unconscious and that gains characteristics in common from the perspective of different people and cultures. In addition to these conceptions about human practices, we observe in another theorist, Erwin Panosfky, the questions about iconology and iconography that are predominant in Tarot, since, initially, these representations were made in a pompous way with the intention of symbolizing and signifying the power of elite to which it was directed.

From the questions of archetypes and their symbologies in Tarot cards, it was possible to establish an analysis that went beyond the iconographies and iconologies of the game, as well as making a historical and artistic temporal cut of the period in which the deck will be made. The way in which countless artists and creators dealt with and observed the feeling of pain, love, pleasure, fear and other feelings and expressions, common to human beings, directly reflects on the conception of what these manifestations represented at that historical-social moment . In this sense, we sought to relate the journey of the Tarot major arcana with the journey of art history.

Having the first card, or the zero card, of the arcane The Fool as the premise of these first steps not only of the reckless, risky and dreamy archetype, but also of the daring and changeable human being. Therefore, understanding the various artistic and social manifestations of the Tarot was the central point of the research as a way of expanding discussions and reflections on the countless transformations to which humanity is conditioned, understanding it as constant and changeable.

General Purpose: Conduct a reflection on the temporal and social changes of the human being, through the prism of art, having the Tarot as the main device of analysis.

Specific objective: in relation to the research, aligned with theorists of the arts, mysticism, history, psychiatry and anthropology, we sought to establish codes that found a common path relating Tarot, art and society. To this end, the following were made:

The obscure origin of the tarot: symbolisms, archetypes and art

The origin of this oracular game that, for centuries, has permeated the human imagination is not known for sure. Being present in esotericism, religions, music, cinema and the arts in general, this curious set of 78 cards, of which 22 of them refer to the so-called major arcana – or mysteries, and 56 to minor arcana, or minor keys, goes beyond aesthetics and encompasses a whole sense of archetype and symbol,3 surpassing the meaning of cards only entrusted with common pictorial value.

One of the earliest possible origins of the Tarot refers to the cards of the Mamluk Sultan, originally titled “Mulūk wa-nuwwāb” (from the Arabic “kings and deputies”), existing in the Cairo region between the 13th and 16th centuries.4

The deck in question would have arrived in Europe and won, among royalty, space as a game of chance. Strictly prohibited by the Church, only later would the deck gain iconographic characteristics, which dialogued with the interests of the monarchy, and would later be used for teaching within the medieval Church itself.3 This first deck can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the four suits that originated in current decks: diamonds, spades, clubs and hearts.

Figure 1 Mamluk Sultan Letters (15th or 16th century).34

Another version of the story tells that the deck would have originated from the great Egyptian book related to the god of wisdom Thoth. In it, each letter was a kind of “page”. During this period, Egypt was being conquered by different peoples. With the aim of preserving the sacred origins and meanings, and hiding them from the invaders, a group of disciples of Thoth would have converted the pages of the book into blades, making what would become a kind of deck. Thoth, then, would be a kind of corruption for what would later be called Tarot.4

As a court game, mainly Italian, Tarot gained a new conception, based on the Mameluco Islamic deck, in which its arcana – at the time called Trumps – symbolized the keys to the game and the person who triumphed in all suits won.5

It is believed that “the first card games to be introduced in Europe were brought from the Islamic world to Florence, Siena, Germany, Switzerland and France around 1377”.5

In this line of research, there is evidence that, from the Mamluk deck, within the notion of the four known suits, Tarot possibly developed in Europe, initially in the Italian court, gaining new artistic representations permeated by the desires and needs of the court at the time.4

The art of the 15th century and the tarot in royalty

The fifteenth century, marked the end of the period known in history as the middle Ages, being a crucial moment for the beginning of the transition of ideas and thoughts of humanity. Soon after a period of famine, plague and social upheavals that occurred in the previous century, medieval thought underwent considerable changes, reflecting in all its aspects.6

In Europe, signs that severe changes were to come were perceptible. Man was close to a new dawn, including in the arts that began to represent individual human aspects. Part of this was a consequence of the Renaissance, when Tarot consolidated and gained its primitive form that extends to the present day.7

The main art forms of the middle Ages included architecture, sculpture and painting, and their main functions were the decoration of monasteries, churches and castles, in addition to religious instruction. Medieval works of art often featured religious themes, such as biblical and hagiographic scenes (reports of saints), and were marked by a decorative and symmetrical style.8

Some notable examples of medieval art include Gothic cathedrals such as Notre-Dame de Paris and Chartres Cathedral, as well as illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells and the Blessed of Liébana. Other forms of popular art in the middle Ages included tapestry, goldsmithing, pottery and music.9

It was within this entire social and artistic context that Tarot developed as a Court game, without any oracular character, closely linked to social stratifications and representing the possible archetypes of that society, in a luxurious and ostensive way, by demonstrating power through painted cards exclusively by hand.3

The iconographic representations of the Tarot were in line with the desires and demands of the philosophy of the Enlightenment and Renaissance, which sought in the classic the real human nature. Greece, Rome, Egypt, Sumeria, among other ancient civilizations, became the subject of studies by various artists, such as Filippo Lippi, Paolo Uccelo, Masaccio, among others.7

One response to these changes was the production of luxury goods commissioned by the court; several of them with religious and mythological inspirations. Thus, the first Tarot packs began to be produced by numerous artists to serve the monarchy.8

Still within this context, there were countless families, among the nobles, who ordered handmade decks, in which the artists used pigments that represented all the power and wealth of that family. As is the case with one of the oldest decks, the Visconti-Sforza Tarot. Produced approximately in 1451, by Bonifácio Bembo (1420-1482), it was commissioned by the Sforza family, who developed a predilection for playing cards, so much so that they also ordered decks of cards with different images from other artists of the time, such as gods, emblematic animals and birds.3

With the power of the monarchy increasing, and the emergence of a State apart from the clerical power giving signs, the Church began a process of “rescuing” the faith and worship of the people, using various means for this, including art. This influenced the iconographic representations of decks that, at that time, began to adopt and adapt some elements for Christian mythological beings, such as the angel, seen in the Arcanum Temperance, and the devil, seen in the card of the same name, The Devil.10

The tarot resurges in the 18th century: the clothing of the occult

Around the middle of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, Western society experienced the so-called “esoteric boom” and, with that, magic gained a new guise.11

The society of the period known by historiography as the Modern Age, through phenomena such as the industrial revolutions, was already freeing itself from the authoritarian power of the Catholic Church. Much of this scenario was due to the consequences of Enlightenment thought and the Protestant Reformation, which brought in their framework the deepest and oldest studies of humanity. This new society sought to respond to their desires and needs, trying to rescue, in the beginnings of antiquity, the moment of intellectual autonomy of man, which had been barred by the Christian faith in the middle Ages.10

The mystical aura gained strength thanks to the Enlightenment which, even condemning or ignoring practices considered unscientific, ended up stimulating anthropological research and studies, leaving the Eurocentric Christian dome and seeking references – including spiritual ones – in other peoples and societies.12

The Tarot was one of those rescues, becoming an object of study focused on the effervescent magical and oracular practices of that period. It was at Golden Dawn, Hermetic order created in 1887 by Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, William Wynn Westcott and William Robert Woodmanna, in England, that it became one of the tools used by its participants.13

The society of the time longed for answers, seeking them in the occult. Art also became the object of manifestations of this philosophical and spiritual quest, which reflected the collective consciousness of a population in transition of ideas and values. With this, it is understood that: “The iconographic mutations of the tarot, therefore, are closely linked to different collective perceptions and patterns of use”.5

Iconographic representations continued in this context, from the Baphomet, by Alphonse Louis Constant (1810-1875), better known under the pseudonym Eliphas Lévi, to the Tarot of Thoth, by Aleister Crowley (1875-1947). The thinkers of that period needed to express themselves through drawings when studying about divination, magic, Satanism and art – as in the Tarot cards, in which there is their whole vision of the world; of that particular world.14

In Figure 2, it is possible to observe the archetypal image of Baphomet, created by the priest and scholar Eliphas Lévi, in his two-volume treatise on magic in the book “Dogma e Ritual da Alta Magia”, published between 1854 and 1856. Human, animalistic and mystical elements, encompasses the concept of wisdom (the flame on the goat's head), in the midst of the human being, and his primitive impulses (the animal parts). This representation does not allude to the figure of a being or entity, but to a symbol of the search for wisdom.15

Figure 2 Baphomet by Eliphas Lévi.15

For the name of the symbol, Lévi was inspired by the ancient accusation of heresy against the Knights Templar, in the first half of the 14th century, made by Pope Clement V and King Philip the Beautiful. Among the various accusations, there was one in which the knights were attributed with worshiping a being with many faces and heads, whose name referred to Baphomet. The accusations were a pretext for the Church to confiscate all the wealth of the knights and, thus, Felipe, El Belo, to achieve his private revenge against the order.16

In the concept, which comprises art as a tool of human expression in Tarot, there is a certain type of order, also linked to aesthetics, which differs it from other sets of cards, allowing greater freedom of creation on the part of the author, who comes to produce the letters within a specific context.5

YEAH! Tarot is pop in contemporary

All cultural accumulation arising from the 1960s, with the counterculture and the growing esoteric influence of the previous two centuries, had its unfolding with the origin of new religions, as a way of escaping from a saturated Christianity at that time.14

In Europe and the United States, in the second half of the 20th century, neopaganism, in particular the Wicca religion of the English anthropologist and occultist Gerald Brosseau Gardner (1884-1964), gained new followers and a series of publications. In Brazil, Umbanda – founded in 1908 by the medium Zélio Fernandino de Morais (1891-1975) – gained popularity, having in its structure the syncretism of Candomblé, Kardecist Spiritism, Catholicism and indigenous traditions.

The Tarot presented itself to these new religious movements as an oracular and consultation tool, not being linked to the structures of doctrines, as was the case of the Golden Dawn.13 Thus, within these rising religions, cards were just a resource used by many of their adherents. At that moment, witchcraft, which, since the Inquisition, from the perspective of Christian dogmas, had been relegated to associations with sin and evil, became “pop”.14

According to the same author, the notion of philosophy, humanity, individuality and magic, connects through oracular and magical practices. The witch leaves the medieval imaginary, as a negative symbol, and wins series and films in which she becomes a heroine, as in the series “Bewitched” (1964), by Sol Sankes, and “Young Witches” (1996), by Andrew Fleming and Peter Filardi.

Tarot followed this trend, being represented in cards linked to references from the media universe, with an iconography of elements common to the great mass and current social guidelines, such as the issue of women in society. It is no longer an object restricted to esoteric groups, being more accessible to the lay public.17

Introduction

The Tarot representations were analyzed taking into account the following aspects: the social, cultural and religious transformations that took place from the end of the 15th century to the beginning of the 16th. To do so, the Tarot card zero was used, the one that starts the entire journey of this unique symbolic system, the card in question is The Fool.

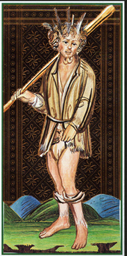

It is noted that the understanding of the Fool – which can be understood as a universal archetype of the imprudent, foolish and even treacherous – in the medieval context, carried several aspects, most of them attributed by the Church (Figure 3).

In Figure 3, there is a very old representation of the letter, in which we see the figure of an individual, with long ears and a carefree face, surrounded by what appear to be children.18

Figure 3 The Fool from the Tarot of Charles VI (1494).32

There is a detail that marks the thinking about madness in that period, in particular, from the perspective of the Church. The pointed ears would be the greatest metaphorical characteristics of a madman, because, in the conception of the time, the madmen, especially those who were in the classification of the so-called, “Artificial fool”19 were devoid of sense, using frankness within the rigid system of hypocrisy that permeated the court.

Close to the king, they were great for bringing news about possible insurrections and betrayals, since they circulated freely – maintaining any kind of attitude – without raising suspicion. The long ears would be, in the view of the Church, the susceptible negligence of the madman in listening to everything that was said to him without reservation.19

Still regarding the vision of the madman, and the way he, with pointy ears, heard everything without moral criteria, the following excerpt from the satirical poem Stultifera Navis – A nau dos Insensatos, in Portuguese – by Sebastian Brant (1458 1521)20 can be observed. ): “... crazy is also the keeper of noise, the credulous person with a fine ear and a wide ear who fills his head with nonsense.” These verses narrate the journey of 111 characters, from different social classes, to the land of madness, Lacagonia, where each one of them represents a vice.

It can be seen, then, how the thought about madness, in that period, influenced the writing of the letter, and how, over time, this letter, with a universal symbolic conception, gains new characteristics corresponding to contemporary anxieties at the moment when will be made.

Variables

The object of study was the letter “O Louco”. As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, it is the initial Tarot card, which can be understood as the starting point of the journey, in addition, this card has important meanings, hence the relevance of studying its versions over the years.

Sample

For the object of study, the letter “O Louco” was chosen, which had its versions analyzed over the years. In this work, considerations began with the 15th and 16th centuries, due to its cut being inserted in the arrival of the Tarot to Europe. Periods between the 18th and 20th centuries were also analyzed, when he became an object of study and mystical practice. And, finally, the 21st century will be investigated, a period in which the Tarot, and its representations, are expressed in parallel with technology and mass culture.

Procedures

For this study, a search was carried out in books and on the internet, in articles and websites specialized in the subject, considering the periods between the 15th and 21st centuries. The letter “O Louco” was used as a reference so that an analysis could be made of how each period influenced it, in its representations, from colors, symbology, and writing, among others.

Working hypothesis

As a working hypothesis, it was possible to observe that:

Waite Tarot (Figure 6) and in the Thoth Tarot (Figure 7), it is possible to observe temporal/social changes in his artistic compositions

In Visconti-Sforza's art (Figure 4), one can see the drawing of the Fool carrying a staff. Her garments are disproportionate, as if parts are missing or as if they are arranged incorrectly. In it, the color palette focuses on gold, probably referring to the power and wealth of that family, and the figure that represents “The Fool is limited to the medieval conception, preached by the Church, about madness in its stereotyped sense.

Figure 4 The Fool of Visconti-Sforza (15th century).33

In the representation of the Fool in Marseille, in Figure 5, one can observe the archetypal figure of the madman accompanied by an animal that seems to attack him. Carelessness, permeated by a certain naivety, is evident in the way the central figure was painted. The position of the legs indicates that the madman continues on his way, even if he is being whipped by an animal, which resembles a cat, symbolizing the material and spiritual foolishness of the arcane.

Figure 5 The Fool from the Tarot of Marseille by Nicolas Conver (1760).21

The Fool's expression, even in the face of the attack, is not one of pain or anger, but of a certain seriousness. It's as if, at that moment, he wasn't worried about listening to other people's conversations or being distracted by children and like one of them, nor was he showing himself capable of self-defense. The clothes, as well as the body expression, demonstrate that this Fool is tired of being distracted or of standing still like a target. He finally goes on his way, ignoring the primary barriers of his condition as an archetype.

In Figure 6, in the Tarot developed by the English mystic Arthur Edward Waite (1857-1942), and made by the artist Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951), The Fool gains elements previously present in the Tarot de Marseille card.

Figure 6 The Fool of Waite-Smith (1910).30

The central figure, male with flowing and colorful clothes, is painted standing to the side, conveying the image of distraction; without facing things head on. The feeling of recklessness and distraction continues, as the central character walks towards the abyss. A new figure appears: the dog, who plays with the Fool trying to warn him about the imminent danger. The Fool in this card no longer uses the staff of his medieval representation, who needed to protect himself from envious people at court because he was close to the king. Waite -Smith 's Fool is simple-minded, silly, reckless, in love with life, without fear, and who, leaving the stick behind, launches himself into the world with his little luggage.

The aggressive Fool, seen in medieval times, became the Joker, the Joker, of the traditional deck that is played today. Crowley's Fool (Figure 7) became a kind of transcendental figure, wrapped in auras and symbols that interconnect the archetypal concept of the card to its own iconography from studies of its creator.

The central figure of this card faces the situation head-on again. In Thoth (Figure 7), the Fool is not distracted, but perhaps takes the risks and the desire to know the occult. A tangle of lines reinforces a kind of “Metatron 's Cube”21 linked to the so-called sacred geometry, associating it with the Archangel Metatron, present in the Jewish Kabbalah, considered the closest angel to God.

Figure 7 Fool from the Tarot of Thoth (1938-1943).27

Still in Crowley's letter, The Fool, painted by the English artist Frieda Harris (1877-1962), has his eyes half-open, apparently, as if he were still unaware of the mysteries and magic around him, trying to consolidate himself.

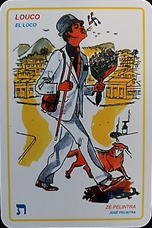

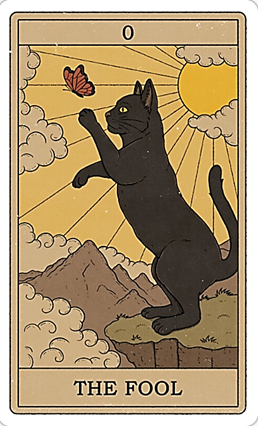

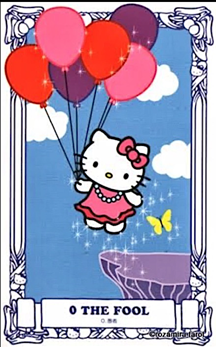

From Figures 8, 9 and 10, it is possible to observe how diversified the iconographic representation of the Tarot has become, without losing the symbolic meaning of the arcane The Fool, seen as a central element that symbolizes carelessness, dreams and dreamlike desire.

Figure 8 represents The Louco Tarô dos Orixás, developed by Eneida Duarte Gaspar,22 in which the Crazy is represented by the figure of Zé Pelintra, who, in Umbanda, would be “an entity surrounded by peculiarities, described as a malandro, a connoisseur of drinks and card player, a black entity that receives several interpretations”.23

Figure 8 The Fool of the Tarot of the Orixás (1994).22

Assuming the form of a malandro, in line with Umbanda, the Fool becomes the figure of Zé Pelintra, exhaling all the aura of daring and contentment with life, accompanied by a caramel dog. The character also brings, in one hand, a bouquet and, in the other, a cane in a purely aesthetic way. On the side, he carries his small bag indicating there is no weight or worries about his choices. He is determined to flirt with life, not afraid to express his style and desires.

In Figure 9, the representation of the Fool by the Tarot dos Gatos deck, the Cats Rule the Earth Tarot, is contemplated.

Figure 9 The Crazy of Cats Rule the Earth Tarot (2022).25

In all cards of this Tarot, the central figures are cats. In them, it is not possible to observe the human or mythological form; the longing to feel part of a whole is converted to pure aesthetics and the individual taste for felines that, for centuries, have been companions of humans, just like dogs.

In Figure 10, a character from children's drawings is shown, Hello Kitty, a kind of humanized cat that, for years, has been an object of consumption both by children and collectors, due to its popular character present in the collective unconscious, as well as Barbie doll and Mickey Mouse.

The figure of the Fool, through the Hello Kitty Tarot (see Figure 10) developed by Ryuji Kagami (1968), takes on an air of dream and fantasy. Despite this, it does not lose the imprudent conception of the essence of the arcane, considering that the main character is represented on the edge of a precipice. However, in the letter, the character is carried by balloons, which symbolizes the power of dreams and fantasy, something very widespread in children's circles.

Figure 10 Arcanum the Fool in the Hello Kitty Tarot.29

The classic figure of the dog or cat that always accompanies the Fool, in the Tarot of Cats and Hello Kitty, is replaced by the butterfly, symbolizing, once again, play, dreams, beauty and distraction.

It can be seen that, from the post-war period onwards, when art began to follow the paths of the contemporary, Tarot and its artistic representations followed the flow, assuming spaces for criticism and new symbologies within those already known in the game for centuries.24,25

It can be said that the Tarot assumes the image of the artistic conception that will best represent it aesthetically, in a given historical and social period. It is interesting for research to investigate, through the images of the cards, the way in which visual change occurs or not over the centuries and in different historical, social and cultural contexts.26,27

Therefore, when carrying out this analysis, it is possible to say that the two specific objectives of this work were fulfilled and, with that, the General Objective, which was “To lead to a reflection of the temporal and social changes of the human being, through the prism of art, having the Tarot as the main analysis device”, was fully met. In addition, the hypotheses of the work were proven throughout the analysis, in which the letter aesthetically undergoes changes arising from the environment in which it is inserted (culture has a great influence on this), but its meaning remains the same, that is, regardless of which deck is used, the meaning of The Fool does not change.28–35

Understanding the journey of Tarot, in the universe of arts and humanity, is not a simple task, given the mysteries that surround the possible origins of this game, and oracle, present in the lives of different people. Whether in the spiritual universe or in the means of analytical science, the Tarot cannot be relegated to a simple game, used in the past as a recreational means of the court, certain that its explicit and implicit nuances are loaded with problems directed at humanity, in an almost homogeneous way, and that accesses a collective unconscious that, bringing much more than simple guesswork, dives directly into the self.

This dip was present in the arts as the most primary way for human beings to represent both their fears, desires and dreams, as well as all the issues that directly crossed the social and personal field. After analyzing the "Fool" letter, at different times in history, it was possible to understand how human beings have expressed their countless perceptions of life and the world, using art and symbologies to interpret the way in which feelings humans can be transcribed. For this, through the idea of archetype, he resorts to figures and elements that were later associated with human practices.

The entire research was mapped taking into account the works and writings of different intellectuals from the most varied means. Some, like Eliphas Lévi,15 allowed an understanding of the Tarot as an element associated with the esoteric environment. Others, like Carl Jung,24 provided the archetypal understanding so present in the Tarot. Authors such as Gonçalves and Reily,19 pointed out the focus on the Fool and his social structure triggered by the deck of cards.

It was understood, then, that symbolic art was linked, at various times, to the period of life of human beings, being a significant expression of something incumbent on us since the Paleolithic. In that distant time, men represented, on the walls of caves, symbols of what they were related to, making this the first steps of this long and intriguing journey of the human being; or the Fool that dwells in us.

None.

None.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

©2023 da, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.