Left ventricular aneurysm (LVA) is known to be a serious health disorder. It has been the observation of clinicians that in most cases, aneurysms develop in the apex wall of left ventricle. The aneurysm can absorb a portion of left ventricular ejection,which may lead to heart failure. Formation of an aneurysm on a ventricular wall,as observed by clinicians,complicates the pathological state of transmural myocardial infarction . However, the hemodynamic factors that are responsible for aneurysmal bulging are not completely known. Bartel et al.1 conducted a study by using a biomechanical model with a motivation of exploring the said factors.They concluded that heart rate, contractility and afterload are the principal factors that cause aneurysm and aneurysmal bulging.The study suggests that in a clinical setting, it should be possible to control the size of bulging through hemodynamic management.

|

Nomenclature

|

|

|

|

Semi-major axes of infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Semi-major axes of pre-infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Semi-major axes of pre-stressed ventricle

|

|

|

Semi-minor axes of infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Semi-minor axes of pre-infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Eccentricity of pre-infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Eccentricity of infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

The bulge factors of the inner and outer bulge

|

|

|

The left ventricular pressure on the innermost surface

|

|

|

The pressure due to infarcted liquid phase

|

|

|

The uniform circumferential stress in all layers of the pre-infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

The tensile stresses in the inner and the outer layers of the middle segment of the infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Volume of the muscle layers of the pre-infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

Volume of the muscle layers of the infarcted ventricle

|

|

|

The angle subtended by the boundaries of the different layers of the infarcted ventricle at their centers

|

|

|

The angle of damage

|

Studies on the mechanical behaviour and mechanism of myocardial infarction are quite useful for analysing the genesis of aneurysms. Deformation of the ventricular wall after infarction involves different mechanical factors; the infarcted myocardium supports the intra ventricular pressure and the incompressibility of the muscle wall. The selection of candidates for coronary bypass surgery depends on the following factors:

- Estimation of the infarct size and location as well as the effect of the intensity of the chamber pressure to continue the circulation during systole, and

- Whether the size of the infarct is enough to cause an eventual aneurysm.

This information is quite useful for having an idea as to how the deformation changes the intra ventricular haemodynamic. They are also helpful for the proper treatment of aneurysmectomy.

The model offers the opportunity to study in a fairly simple way the influence of a number of relevant features connected to ventricular geometry and muscle contraction based as much as possible on current physiological knowledge. Such studies also make it possible to estimate the diastolic and systolic properties of the heart, the ventricles and muscle before and after interventions. Of course, this approach leads, in general, to relatively complex models with a number of parameters.

According to Huxley’s theory,2 force generation by the sarcomeres in response to activations results from chemical interactions, which can be demonstrated by electron microscopy in skeletal

muscle. But structure of sarcomere in cardiac muscle is the same as the striated muscle. The sliding filament model of Huxley2 has been extensively applied to muscle mechanics, since it satisfies the thermodynamic data of striated muscle reported by Hill.3 Van Den Broek and Van Den Broek4 improved the model of heart as a nested set of thick-walled truncated ellipsoid of revolution with nonuniform wall thickness. The shells contain muscle fibres which generate wall tension, from which ventricular pressure results. Fiber length and orientation per shell were taken to have different values.

The geometry of the left ventricle was idealized as a thick-walled circular cylinder and the myocardium was assumed to be composed of an incompressible homogeneous and isotropic material in an investigation undertaken by Moskowitz5 to explain the physiology underlying left ventricular diastolic phenomena. Different mathematical models for left ventricle were also tried in the past by several researchers to estimate the stresses in the left ventricular wall. Misra and Singh6–10 carried out several studies relevant to the mechanics of the left ventricle in normal and pathological states. Some recent investigations of aneurysms in the left ventricle are given by.11–13

The mechanical behaviour of aneurysm formed in an arterial wall was studied by Ren and Yuan.14 They predicted that the aneurysm may rupture if the stress at the arterial wall is greater than its strength. A theoretical study was performed by Misra and his collaborators15 for the study of the mechanics of carcinogenic human arteries. The study was motivated towards finding theoretical estimates of hemodynamic flow during electromagnetic hyperthermia. Misra et al.16,17 also reported their results for two separate studies on blood flow in the micro-circulatory system, which bear the promise of important applications in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

In 2019, Sui et al.18 carried out a statistical analysis for 183 patients with left ventricular aneurysm (LVA). Based on their observations, they discussed the efficacy of three different clinical treatment methods, out of which they suggested that surgery is the best treatment option for the treatment of LVA. Based on another statistical study, Ohlow19 made some important observations on the characteristics of congenital left ventricular aneurysms. Discussion on different aspects of surgical treatment of left ventricular aneurysm was made in,20–22 while impact of surgery on patients with LVA was discussed in.23–25 It is important to note that Pasque26 and Kramer et al.27 while discussing about left ventricular aneurysm repair stressed upon the importance of application of mathematical modelling theory to validate the observations of clinical investigations in cardiac mechanics and cardiac surgery.

A finite element model was employed by Guccione et al.28 to study the mechanism behind the mechanical dysfunction in the border zone of left ventricular aneurysm. The study shows that myocardial contractile dysfunction is more responsible for mechanical dysfunction in the said region of the aneurysm than the intensified wall stress developed there. The left ventricle with an infarcted wall was modelled as a spherical shell by Radhakrishnan et al.29 to perform a mathematical analysis of ventricular aneurysm that develops due to infarcts of different sizes. Based on this analysis ventricular wall deformation and stress were calculated. The study shows that the innermost layer is affected most severely, where the stress developed is maximum. The extent of wall damage was obtained in terms of the angle of damage and percentage of damage of the ventricular wall.

However, in the studies mentioned above, for the sake of simplification, the left ventricle was modelled as a spherical shell and so the eccentricity of the left ventricle was not taken into account. However, it is well-known that the eccentricity of the left ventricle is non-zero. In order to account for the effect of eccentricity and structural non-homogeneity on left ventricular aneurysm, the present study has been carried out by developing a mathematical model, in which the left ventricle is considered as an ellipsoidal shell, consisting of three distinct layers. The mathematical analysis has been performed by employing suitable analytical techniques. The model and the results obtained therefrom have been duly validated by comparing the results of this investigation with those of previous studies available in the existing literature.

The Model

On the basis of the assumption of muscle incompressibility, the volumes of the three muscle layers may be taken to be the same before and after infarction. If the area of damage is not too large, the infarcted segments preserve the ellipsoidal form, of course, with different eccentricity after the development of the aneurysm.

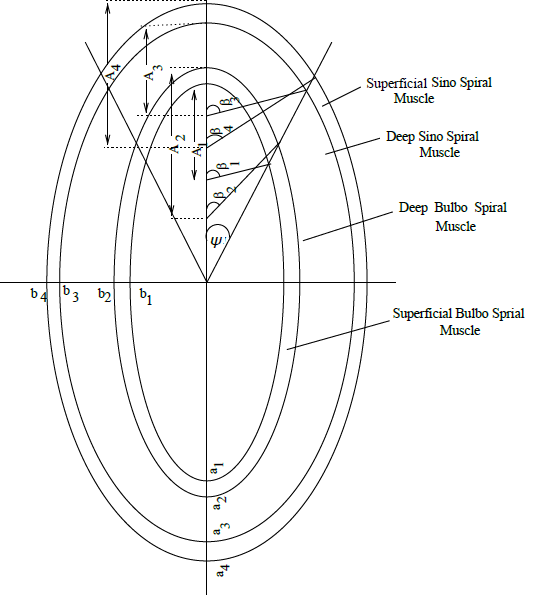

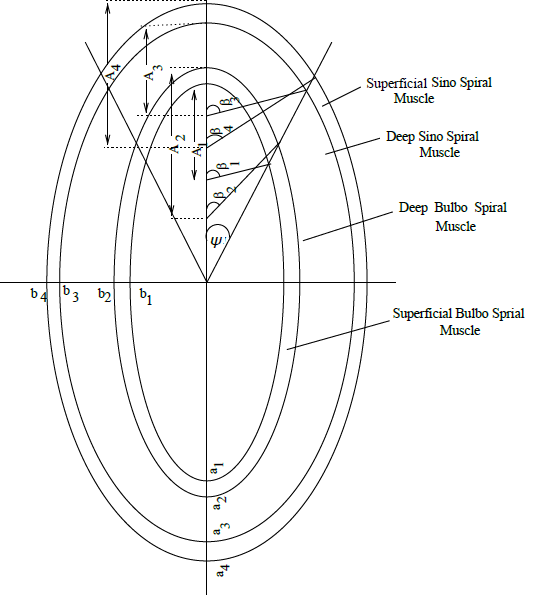

As already mentioned, the left ventricle is modelled as a three layered ellipsoidal shell of revolution; the major and the minor semi-axes of the non-infarcted muscle layers are denoted by

(at the inner boundary of superficial bulbospiral muscle),

(at the inner boundary of deep bulbospiral muscle),

(at the outer boundary of deep sinospiral muscle) and

(at the outer boundary of superficial sinospiral muscle). A schematic diagram has been presented in Figure 1. The corresponding values for the infarcted layers are denoted by

respectively. Observations of previous investigators indicate that the set of ellipsoidal shells before infarction are concentric and further that the ratio between the minor and major axes is approximetly 0.87 for all the layers. The non-uniform thickness varies according to the law of incompressibility. The infarcted layers have the same eccentricity but differ from non-infarcted layers. Let

and

are respectively the eccentricities of the non-infarcted and infarcted layers. The major and minor semi-axes of the three different infarcted layers are assumed to be

and

respectively.

Figure 1 Schematic Representation of the Layered Ellipsoidal Structure of Left Ventricular Aneurysm.

Let

be the angle of damage; this is the angle made by the three concentric layers initially at their center and let the bulged segments subtend the angles

and

respectively at their centers.

The following assumptions will be made here.

- The myocardial wall is composed of three layers viz. (i) superficial sinospiral muscle, (ii) deep sinospiral muscle and deep bulbospiral muscle and (iii) superficial bulbospiral muscle. The muscles are treated as incompressible material.

- The two superficial layers remain unaffected but damaged deep layers are assumed to be replaced by an equivalent amount of fluid. This infarcted zone deforms into ellipsoidal caps, the outer and inner superficial layers are similar in all respects. Also the undamaged portion preserves the same shape.

- The left ventricle is treated as a closed pressurized chamber loaded by intraventicular pressures at the instant prior to the opening of the aortic valve. The segment of the middle layer of the wall becomes infarcted at the apex. Thus the inner bulge of the infarcted zone is caused due to the resultant of intraventicular and fluid pressures, while the outer bulge supports the fluid pressure.

- Mechanical behaviour of aneurysm is considered only at the instant prior to the opening of the aortic valve.

- The length-tension relationship used as the contractile tension is a linear function of contracted length.

- Necking is neglected near the edges of infarct.

Assuming that innermost segment of the pre-infarcted left ventricle is bounded by the part of the ellipsoidal shell whose major and minor semi-axes of the inner and outer boundaries are

and

respectively, as in,30 calculations necessary for the present study have been performed. They are presented below.

Volumes before and after infarction

The predeformation volume of the innermost infarcted wall segment is given by

(1)

(2)

and

(3)

After infarction, the ellipsoidal segment is bulged out to a different ellipsoidal segment. For the innermost layer, the inner and the outer surfaces of the segments whose major and minor semi-axes are

and

subtend the angles

and

at their centers. Similarly, for the middle and outer bulged segments having

and

as the semi-axes, angles subtended at the centre are

and

and

and

respectively.

Now the volumes of different bulged out segments are

(4)

(5)

and

(6)

Using Figure 1 and considering the incompressibility conditions, we get the following geometrical relations:

(7)

(8)

(9)

and

(10)

Making use of the relations (1)-(6) together with (7)-(10), the differences in the volumes before and after the formation of the aneurysm of the inner, middle and outer portions are found as

(11)

(12)

and

(13)

The expressions (11)-(13) should be equal to zero on account of the incompressibility condition.

Stress equations of equilibrium and length-tension relationship of the muscle layers for the inner and outer bulges of the aneurysm

Let

be the left ventricular pressure of the undamaged portion of the ventricle,

the uniform circumferential stress in all layers of the undamaged ventricle and

the tensile stresses on the inner and outer surfaces of middle segment of the bulged portion. For the equilibrium of the undamaged ventricle, we have

(14)

Considering a segment of the innermost layer of the undamaged left ventricle, we find that it is in equilibrium under the action of the ventricular pressure on its inner surface and a pressure

exerted by the liquid phase of the infarcted region. Thus we can write

(15)

Similarly, if we consider a segment of the outermost layer, we may observe that the pressure

is exerted on its inner surface, while the outer surface is free of tractions. Thus in order that the equilibrium of this segment is maintained, we must have

(16)

Elimination of the quantities

and

from the equations (14)-(16) yields

(17)

This equation may be written in the form

(18)

In the sequel, we shall make use of the following approximations:

These approximations are valid for the case when the innermost and the outermost layers of the infarcted region of the left ventricle under consideration are sufficiently thin.

Now using the geometric relations (7)-(10) , we have from (18):

(19)

The bulge factor defined as the ratio of the height of the bulge above the centre of curvature to the pre-infarct height is given by

(20)

and

(21)

The contractile muscle stress ratios

and

are defined as the ratio of the average stresses in the infarcted region to the stresses in the corresponding non-infarcted zone. For cardiac muscle, the contractile tension is a linear function of the contracted length. Thus the tension factor may be expressed as

(22)

= ratio of tensile stresses in the strained outer bulged layer to the tensile stresses in the unstrained normal layer,

(23)

=ratio of tensile stresses in the strained inner bulged layer to the tensile stresses in the unstrained normal layer.

In the above expressions,

and

represent the semi major axes of the inner and outer bulged layers in the state of zero stresses; their values are nearly 0.75 of their corresponding values in the deformed state.

Numerical results

The expressions (11)-(13) when equated to zero(due to incompressibility condition) yield three equations involving the parameters

and

. The same parameters are also involved in the equation (19). This set of four equations was solved by employing the Newton-Raphson method. The values of

thus obtained were used while computing the values of the tension factors as well as the bulge heights. For computational work, the cavity volume was taken to be 135 ml; also the following values of the parameters were used:

Four values of ψ (half the angle of damage) viz.

were examined.

Numerical results of the computational work carried out on the basis of the present analytical study are shown in Table 1.

2ψ |

|

|

|

|

20o |

0.65 |

0.66 |

0.61 |

0.81 |

40o |

4.00 |

4.10 |

0.30 |

0.66 |

60o |

6.90 |

7.20 |

0.20 |

0.61 |

80o |

9.10 |

9.90 |

0.14 |

0.60 |

Table 1 Computed values of the tension factors and the bulge factors

The order of magnitude of the above values agrees with the corresponding values of Radhakrishnan et al.29 who considered a spherical shell model for the left ventricular geometry by taking help of different approximations. For the sake of a comparison of the results of the present study with the those of,29 the results corresponding to

are shown in Table 2.

Angle of damage |

40o |

60o |

Present study |

4.0 |

6.90 |

Study of Radhakrishnan et al.29 |

5.20 |

6.6 |

Table 2 Tension factor for the inner bulge

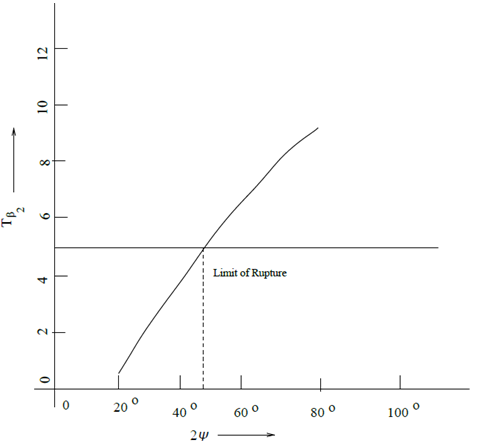

The line

is found to intersect the plot for

of our present study (Figure 2) at a point whose abscissa is

while this value was found to be

by Radhakrishnan et al.29 This difference may be attributed to the combined effect of eccentricity and layered structure of the left ventricle, considered in our study.

Figure 2 Tension factor for the inner bulge vs. angle of damage.