Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6410

Clinical Images Volume 10 Issue 4

Department of neurosurgery, Hassan II Hospital, University Sidi Mohammed Benabdellah, Fes, Morocco

Correspondence: F Lakhdar, Department of neurosurgery, Hassan II Hospital, University Sidi Mohammed Benabdellah, Fes, Morocco

Received: June 06, 2020 | Published: July 6, 2020

Citation: Lakhdar F, Benzagmout M, Chakour K, et al. Post-operative compressive pneumocephalus: A rare complication of lumbar spinal drainage. J Neurol Stroke. 2020;10(4):127-128. DOI: 10.15406/jnsk.2020.10.00425

Compressive pneumocephalus is a rare condition, most often secondary to head trauma or surgery. We report post-operativecompressive pneumocephalus in a patient who underwent primary surgery for anterior clinoidmeningioma complicated by CSF leakage treated by lumbar spinal drainage. CT scanclearly demonstrates a compressive pneumocephaluswith the sign of the Mount Fuji. The patient was treated with definite bed rest and plenty of fluid replacement with good outcome. Compressive pneumocephalus is a serious, infrequent complication anda possible cause of postoperative worsening.Medical treatment combining highly inspired oxygen therapy and rehydration are sufficient to correct the condition.

Keywords:hydration, oxygen therapy, pneumocephalus

Mr A.H, 69 y old women, with a history of mitral valve disease, admitted in our department for a meningioma of the anterior clinoid process revealed by facial neuralgia in the territory of V1 evolving for 5 years and becoming resistant to medical treatment with carbamazepine.The clinical assessment of the patient at his admission showed a conscious patient with a Glasgow coma score (GCS) of 15, without neurological deficit or visual trouble.

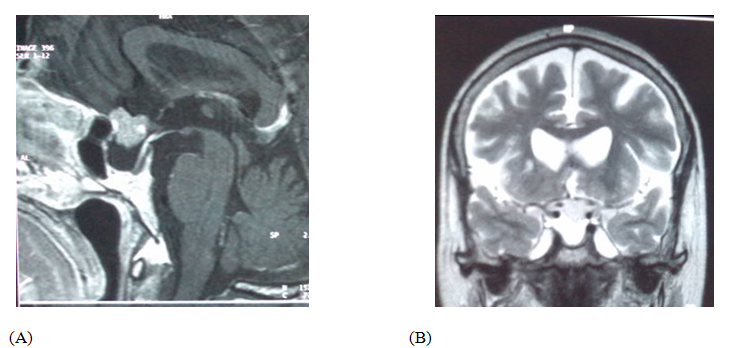

The cerebral MRI showed a sellar lesion inserted on the anterior clinoid process in hyposignal T1, hypersignal T2 with homogenous enhancement after gadolinium injection suggesting meningioma(Figure 1). Gross total removal “Simpson I” by left pterional approach was performed and the histopathological exam confirmed transitional meningioma. The post-operative course was marked by the anterior left and posterior rhinorrhea as well as meningitis, treated successfully by antibiotics with lumbar spinal drainage. However, 3 days later, the patient accidentally fell from her bed causing a CSF hyperdrainage bringing back more than 800CC, accusing excruciating headaches and disturbances of consciousness (GCS =12) without neurological deficit.

Figure 1 Cerebral MRI sagittal weighted T1 contrast (a), and coronal T2 showing anterior clinoid process meningioma with homogeneous enhancement (a) and hyperintense T2 (b).

CT scan showed a huge compressive bifrontalpneumocephaluswith the Mount Fuji sign (Figure 2). The decision made is to treat the patient using a rehydration regimen with daily control by an ionogram, bed rest, plenty of fluid replacement and clamping the spinal drainage. The outcome was favorable with a return to a clear consciousness without rhinorrhea or neurological deficit, also with a good control of brain CT (Figure 3).

None.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2020 Lakhdar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.